President Obama’s announcement that the United States intends to purchase a maximum security prison in Thomson, Illinois, and plans to move as many as 100 remaining Guantanamo detainees there has prompted a variety of criticisms from right and left. Not-in-my-backyard populists oppose holding these prisoners anywhere in the United States (though in a classic prison-industrial complex move, the Obama administration realized that those concerns can be bought off with a promise of bringing 3,000 jobs to a depressed, rural Illinois region).

“War on Terror” advocates complain that we shouldn’t be bringing dangerous terrorists into the United States, and that to do so, especially when coupled with the decision to try Khalid Sheikh Mohammed for the 9/11 attacks in a civilian criminal court in New York, is to abandon the “war paradigm” that should govern our approach to dealing with al Qaeda. They worry that bringing the detainees to the United States will afford them rights they otherwise would not have. Meanwhile, groups such as Human Rights Watch and the ACLU complain that moving Guantanamo to Thomson will solve nothing unless the Obama administration also abandons the practice of preventive detention that Guantanamo signifies—all detainees should be tried criminally or released, they say.

The Obama administration plans to try some, such as KSM, in civilian criminal court, but will try others in military commissions, and will continue to hold still others without charge in military preventive detention. (The military commissions will be based on a 2009 statute that makes the proceedings more fair, but still leaves them short of the procedures we accord our own service members in courts-martial. The administration will choose who gets tried in which forum, according to a range of criteria including the nature of the crime and whether the target is military or civilian, that leave it wide discretion.)

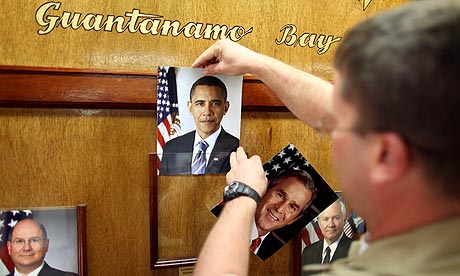

As we approach the one-year anniversary of President Obama’s inauguration, his decision to close Guantanamo, return those who can securely be released to other countries, and bring the detainees into the United States is an apt symbol for the way the president has handled terrorism since assuming office. He has been acutely attentive to the importance of adhering to the rule of law, and to the power of symbols in this struggle. At the same time, he has angered both right and left with his combination of principle and pragmatism. And his record on national security issues remains very much a work in progress, as is the project to shut Guantanamo.

The president had no option but to close the island prison after his predecessor’s policies there turned it into a notorious symbol of the United States’ arrogant disregard for international law. It need not have been so. The mere idea of holding one’s enemies during armed combat should not be controversial. Had President Bush adhered to the laws of war, including the Geneva Conventions—holding only those fighting against us, providing fair hearings to ascertain individuals’ status, treating the detainees humanely, and conceding that absent criminal convictions, they would be repatriated once the conflict in Afghanistan concluded—Guantanamo would not have become an international embarrassment.

Instead, President Bush treated Guantanamo as the ultimate loophole—a place where no law applied, where no courts could act, and where the president’s power was literally unchecked. As a result, by the end of his term, virtually everyone, including President Bush himself, agreed that Guantanamo was doing us more harm than good. But it was left to President Obama to take on the difficult task of closing it.

The only way out of the mess at Guantanamo was to reverse course and treat the detainees strictly according to law. Bringing them to the United States is consistent with that goal, even if it means extending them rights they might otherwise not have. If we need to rely on denying the detainees basic human rights in order to hold them, we are doing something wrong.

President Obama’s most important shift in counterterrorism policy, reflected in his May 2009 speech at the National Archives, was to insist that we pursue our goals within the constraints of international and domestic laws, not outside them. The rule of law can and should be a tool in fighting terrorism, because if we are seen as responding in legitimate ways, we are less likely to build sympathy for al Qaeda and other radical groups hostile to the United States.

Contrary to what Obama’s critics on the right have been saying, there is no contradiction between using military force and recognizing the basic human rights of those we are fighting against. Nor, as his critics on the left maintain, does the rule of law require that the United States renounce all military tools when dealing with terror. The attacks of 9/11 were both an abominable crime and an act of war, and the law recognizes the right of the state to respond by means of law enforcement, the military, or both.

Advertisement

An integral part of a military response is the detention of those fighting against us in an ongoing armed conflict. For better or worse—mostly worse—the conflict in Afghanistan with the Taliban and al Qaeda continues. And as long as it continues, the United States should be entitled to hold those fighting against us. It should do so only pursuant to law, with scrupulously fair hearings to ensure that we are holding only our enemies. But military detention is an appropriate weapon in the government’s arsenal. President Obama has not given it up, as some rights activists (unrealistically) hoped he would. But he has shown a willingness to subject such detention to the rule of law. And for that, he deserves credit.

Still, much remains unsettled. Why, for example, should judicial review not extend to those detainees we chose to detain at Bagram Air Force Base outside Kabul instead of at Guantanamo? The Obama administration is arguing in court that Bagram is beyond the law because it is not Guantanamo, and is closer to the battlefield—an argument disturbingly reminiscent of the Bush White House. Our detention policy should be consistent across the board.

In addition, any long-term detention policy should have the backing of both political branches, and not be a unilateral creation of the executive branch. Thus far, it has largely been the latter, and Obama has shown no inclination to receive Congressional backing for what could be long-term preventive detention in the United States. Nor has he expressed an interest in pursuing accountability for those in the US government who committed crimes in the name of fighting terrorism as I and others have urged—in particular, for the lawyers and officials who twisted the law to authorize torture and cruel treatment of detainees. How the administration responds to the forthcoming ethics report on the Justice Department lawyers who authorized torture will be an important signpost.

In the end, what is most critical is our attitude toward the rule of law. As former Israeli Supreme Court Justice Aharon Barak famously said in a 1999 decision barring the use of physically coercive interrogation against suspected Palestinian terrorists, “a democracy must fight terrorism with one hand tied behind its back. … Preserving the rule of law and recognition of individual liberties constitute an important component of its understanding of security. At the end of the day, they strengthen its spirit and strength and allow it to overcome its difficulties.” Closing Guantanamo is a step in the right direction; but in itself it is not enough to repair the damage.