I first saw Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1926) sometime in the Sixties in a miserable 16-millimeter print under 90 minutes in length. Drastically cut not long after its premiere engagement in Germany, the film had been slashed ever further in subsequent editions. One of the most influential films ever made—the font of cinematic dystopias, a source of imagery reflected in films from The Bride of Frankenstein to Blade Runner—is only now being recovered in nearly its intended form. The 2001 restoration which brought it to 120 minutes was a revelation; that has now been surpassed, thanks to the discovery of additional footage in a Buenos Aires archive. At 147 minutes, the new Metropolis is just six minutes shy of the original running time, even if the newly restored footage is in sadly deteriorated condition. It hardly matters: to see Metropolis in its original form is to discover not just the new material but all the rest; the restorers have not simply added deleted episodes but expanded existing ones, and the film’s rhythms and internal rhymes are disclosed as if for the first time.

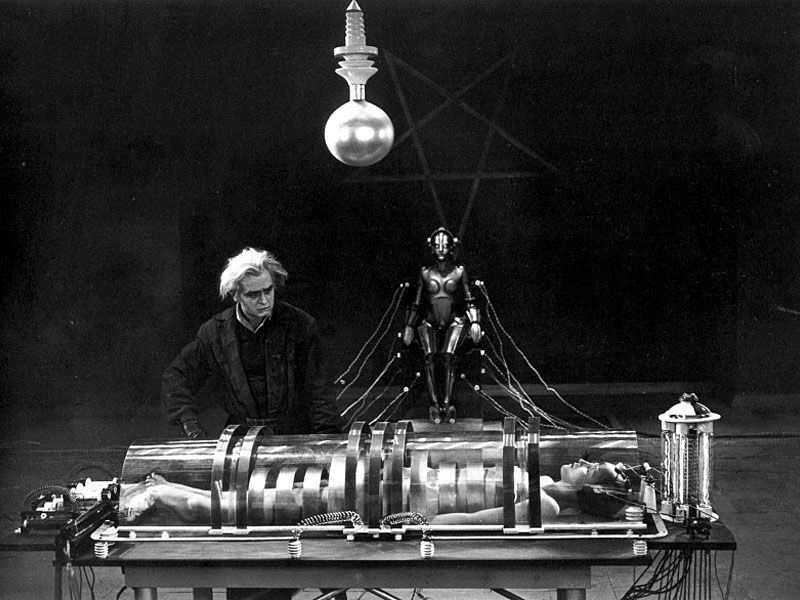

Several whole subplots emerge from darkness, most crucially the conflict between Metropolis’s autocratic chief executive Fredersen and the scientist Rotwang (prototype for all mad scientists to come) over the dead woman they both loved, to whom the scientist has erected a private monument and in whose memory he launches a campaign of undiscriminating revenge. More than before, Metropolis becomes the story of Rotwang’s morbid obsession with the lost woman, which will prompt him to use a robotic simulacrum of the saintly heroine Maria as his agent for bringing down the entire city.

The ideas ostensibly explored by Thea von Harbou’s screenplay—culminating in the schematic happy ending in which Head (i.e., Capital) and Hands (Labor) are joined through the mediation of Heart—remain as unpersuasive as ever. (Who ever remembers Metropolis as a vision of harmonious reconciliation?) The film’s power as a prophetic poem, by contrast, seems redoubled. The overpowering Tower of Babel episode—in which Maria tells a variation of the biblical story to a group of workers gathered in a cathedral—seems less singular, its tone of imminent disaster more evenly diffused throughout. It is both epic and claustrophobic, its vertiginous perspectives (aerial highways, murky labyrinths, elevators moving up and down through different levels of reality) somehow never penetrated by the light of day. Both the elite pleasure gardens and proletarian depths seem utterly enclosed, as if the film took place inside someone’s head.

Within that world, times past, present, and to come are mashed together. The futuristic cityscapes supposedly inspired by Lang’s first view of the New York skyline are filled out now by more extensive coverage of the daily life of Metropolis, scenes of surveillance, deception, and decadent indulgence more than a little reminiscent of the evocation of Weimar Germany in Lang’s Dr. Mabuse der Spieler (1921–22). In the final scenes, now greatly lengthened, of refugee children fleeing cataclysm, it is not hard to imagine a foreshadowing of scenes yet to come, just as the total conflagration that ended Lang’s previous work, Die Nibelungen (1922–24), can seem to have broken through from a future still in the making.

The archaic world of Die Nibelungen is not far from Metropolis. In the heart of the city of the future, the Middle Ages seem poised for an apocalyptic resurgence. The scientist Rotwang inhabits a Brothers Grimm house sprouting like a poisonous mushroom amid the modernist architecture; in a Gothic cathedral a preacher reads from Revelation and the skeletal scythe-wielding figure of Death leads a dance of the seven deadly sins; a woodcut of the Whore of Babylon takes modern form as the False Maria unleashes her seductive powers on the clientele of the luxurious brothel Yoshiwara, sowing violence and despair. Finally the vengeful mobs of the lower city will take their revenge in an act of witch-burning.

The commercial failure of Metropolis led to its truncation, and also helped ensure that Lang would never again command either such an enormous budget (it contributed largely to UFA’s eventual bankruptcy) or such freedom. Many of his later films (House by the River, Beyond a Reasonable Doubt) show how far he could go, making a virtue of necessity, in the direction of minimalist abstraction; but the restored Metropolis allows us to savor the splendor of an art able to realize itself with unrestrained extravagance. It continues to send out its peculiarly unsettling light, like Rotwang’s flashlight among the catacombs.

The new restoration of Metropolis will be shown in theaters throughout the US this summer.