Sari Nusseibeh and Amos Oz were jointly awarded the Siegfried Unseld Prize in Berlin on September 28, 2010. “A Tragic Struggle” and “The Magic Within Us” are drawn from their acceptance speeches.

A Tragic Struggle

Amos Oz

When I was small my parents told me: One day, not during our lifetimes but during yours, our Jerusalem will develop into a real city. I didn’t understand what they were telling me. Jerusalem was the only real city in my life then—even Tel Aviv was just a dream. But today I know that when my parents said “real city,” they meant a city with a river in the middle and bridges over it—a European city. And in Jerusalem of the 1930s and 1940s they nearly succeeded in creating a little Europe, with good manners—Frau Doktor and Herr Direktor, peace and quiet between two and four in the afternoon, and red shingled roofs. I know that my parents’ love for Europe is called unrequited love. And I know that this feeling of love unrequited by the land of one’s birth is also felt by millions of Israeli Jews who fled or were expelled from Islamic countries—from Iraq, Morocco, and Egypt. Jewish Israel is a refugee camp. Palestine is also a refugee camp.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is a tragic struggle between two victims of Europe—the Arabs were the victims of imperialism, colonialism, repression, and humiliation. The Jews were the victims of discrimination, persecution, and finally of a genocide without parallel in history. On the face of it, two victims, especially two victims of the same oppressor, should become brothers. But the truth, both when it comes to individuals and when it comes to countries, is that some of the worst fights break out between two victims of the same oppressor. The two sons of an abusive father will each see in his brother the face of his cruel father. And this is the case with the Jews and the Arabs—each of us sees the other in the image of the former oppressor. The Arabs look at Jewish Israel and do not see it as it really is—a half-hysterical refugee camp. Instead, they see it as the long, arrogant, oppressive, and exploitative arm of European colonialism. We Jews look at the Arabs and instead of seeing them as our fellow sufferers, we see the persecutors of our past—the Cossacks, the antisemites. Nazis who grew moustaches and got suntanned, but who are still eager to slaughter us.

The core of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is a clash between right and right, and often it is a clash between wrong and wrong. The Palestinians are in Palestine because Palestine is the land of the Palestinians just as Greece is the land of the Greeks and Norway is the land of the Norwegians. The Israeli Jews are in Israel because they have no other homeland and, as a nation, they never had any homeland other than the Land of Israel. The Palestinians have nowhere else to go, and neither do the Israelis. The disputed land is, altogether, smaller than Holland—yet there is no choice but to divide it into two countries, Israel and Palestine. The Israelis and Palestinians can’t turn into a single people living in a single country, and there is no point in trying to shove them into a double bed after a century of violence and hatred. No one would have dreamed, immediately after World War II, of trying to make Germany and Poland into a single country. The Israeli Jews and the Palestinians Arabs cannot, at this stage, turn into one happy family because they are not one, they are not happy, and they are not a family. They are two unhappy families, which is why it is vital to split the house into to smaller apartments—just as the Czechs and the Slovaks did without shedding a drop of blood.

These are times of renewed hope. The distance between the Israeli and Palestinian positions in the peace negotiations is not small, but it is certainly much smaller than it has ever been during a hundred years of conflict. It is hard to be a prophet, especially in Jerusalem—the competition is fierce—but allow me to conclude with a small prophecy: A day will come when there is an Israeli embassy in Palestine and a Palestinian embassy in Israel. And these two embassies will be walking distance from one other, because one of them will be in West Jerusalem, the capital of Israel, and the other will be in East Jerusalem, the capital of Palestine. Extremists on both sides will continue to do all they can to thwart a historic compromise and peace—but peace will come, because a majority of both peoples want it and because the extremists are minorities on both sides.

Advertisement

And when peace comes, one of its heroes will be my fellow winner of this distinguished prize, my friend Professor Sari Nusseibeh. Sari has been fighting for decades for a pragmatic peace, a peace of compromise, a peace in which each side gives up, for the sake of the future, some of its dreams and some of its sense of historic rights. Sari Nusseibeh’s book, Once Upon a Country, engages in an overt and fascinating dialogue with my A Tale of Love and Darkness. Sari and I were born just a kilometer or two from each other, he in the neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah and I in Kerem Avraham, a twenty-minute walk. Yet these were two worlds, separated by walls of hatred, fear, and violence. Sari’s excellent book has helped me understand better the other side of the story, and to see the similarity beyond the differences and the common beyond the disparity. It is written with honesty, sadness, courage, and devotion to the idea of compromise and peace.

If you were to seat Sari Nusseibeh and me in an anteroom off this hall, we could, within a few hours, draft the outline of a peace agreement between Israel and Palestine. Both of us believe in a historic compromise and in coexistence, and both of us believe that we cannot allow the anguish of the past to strangle the promise of the future. It is my great pleasure and honor to share the Siegfried Unseld prize with my friend Sari Nusseibeh. But the truly big prize that I hope to share one day with Sari is peace itself.

The Magic Within Us

Sari Nusseibeh

With everyone’s eyes set on the latest round of Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, and with foreign journalists busily scanning Palestinian territory for signs of renewed settlement activity as if for a mysterious portent of things to come, there must be millions of questions on everyone’s minds. What has in recent years become the conventional model for peace, namely, the two-state solution, or a two-state solution, is now up for the test. Let us hope it passes this test—though with a House fractured on the Palestinian side, a narrow-minded Government on the Israeli side, and a pathetically feeble international community, prospects for such a success seem dim.

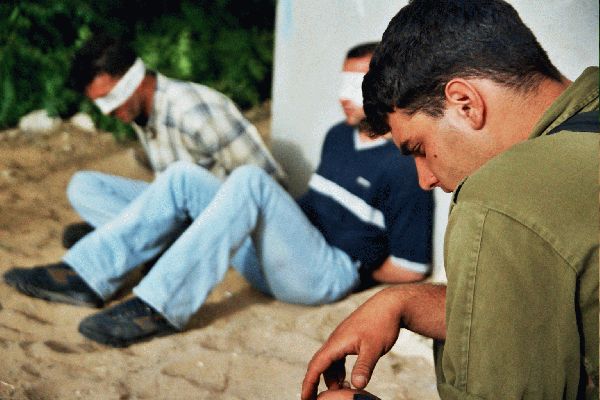

Military moralists on the Israeli side will meticulously weigh, to the last individual, the number of Palestinian civilians whose lives could be dispensed with for the life of an Israeli soldier, while Palestinians, from an equally high moral ground, but with less attention perhaps to numbers, or to soldier-civilian distinctions, will carry out with equal moral conviction the taking of Israeli life. Such, then, are our naive narcissistic beliefs about ourselves, whereas, truth be told (and once transcendental terms are invoked) nothing sets Jewish blood apart from Arab blood, or vice versa, and Arabs might as well be Jews in some other world, or the contrary, their this-world identities really being as discardable, or dispensable, as masks at a vanity ball.

Other voices have recently been calling for different paths toward a solution. Again, though, it is hard to see how commonly agreed-upon progress along such paths can be made. In a way, Israel has fallen victim to its own power, forcing it to be alone at this juncture in being able to identify and to seek solutions for its predicament. Most likely, it will seek half-way measures, necessarily therefore with “half-way” Palestinian representation or leadership, with the hope that somehow, sometime in the more distant future, this “containment” of the problem will somehow make it, or help it disappear. On the Palestinian side, on the other hand, it is the power of their own rhetoric to which Palestinians have traditionally fallen victim.

Under such circumstances, it seems what we have to expect and will all have to prepare ourselves for are not only the long-term results of creeping convergences of population masses and the collapsing of urban spaces—making geographic partition of whatever description an outdated currency from the past—but also the pressing predicament of a binary moral system, where jailers and prisoners are confined to the same diminishing space, each side becoming more a victim of its mischievous tribal mask by the day.

Being who, or what one is has always been a source of mystery to me. One particular offshoot of this mystery, one which has kept nagging at me, constantly upsetting my peace of mind, especially as someone whose entire life has been engulfed in what often seems like senseless conflict, is why, from a logical point of view, I or anyone should fight or fight back for anything, whatever the cause, even if this were the preservation of one’s own life, let alone a piece of territory or a rock or a tribal identity.

Advertisement

My moral disparagement of tribal war and contestations over boundaries of different kinds and sizes should not be understood as harboring a latent quietism—a belief that suffering misfortune with serenity is the only rationally defensible doctrine. Quite the contrary, I am a strong believer in activism, or in acting as the way of being. But such activism, I believe—this belief now being upheld by a tinge of Kantian rationalism—must first and foremost be on behalf of universal human values rather than tribal prejudices. If I stand up for Palestinian rights, then I can only allow myself to do so, and only to the extent, on rational grounds, that I can consider my upholding of such rights to be a specific example of my upholding of universal human rights. My fighting or activism in this case would then be rationally defensible, but only insofar as it has been made so by virtue of this universal moral principle.

I don’t believe that the angel of peace has departed, or is about to leave us forever. But I think that our challenge as peace-seekers, as human beings, is being made far more daunting than it has been. This certainly requires us to be patient; but more than ever, it also requires us to have faith in ourselves, in the magic within us, that however impossible things may look, we can still make them happen. They may not happen the exact way we now think they should happen. But how they may happen may turn out to be even better.