One Saturday last month I went to Lafayette Park in Washington D.C., across the street from the White House, in order to protest several wars. The squirrels were out doing seasonal things. A tree was balancing big buds on the finger-ends of its curving branches; the brown bud coverings, which looked like gecko skins, were drawing back to reveal inner loaves of meaty magnolial pinkness. A policeman in sunglasses, with a blue and white helmet, sat on a Clydesdale horse, while two tourists, a father and his daughter, gazed into the horse’s eyes. The pale, squinty, early spring perfection of the day made me smile.

The demonstration wasn’t officially supposed to start until noon, but already off in the distance a few hundred people had gathered near a platform festooned with a row of black-and-white Veterans for Peace flags. It was March 19, the eighth anniversary of the shock-and-aweing of Iraq, and there was an air of expectancy: arrests were going to happen that day. I sat down on a bench and watched volunteers setting up loudspeakers. Birds were getting in as much chirping as they could before the human noise began. A woman with an armful of red and black signs passed by. Her signs said:

STOP THESE WARS

EXPOSE THE LIES

FREE BRADLEY MANNING

Jay Marx, head of Proposition One, a nuclear disarmament group, took the microphone. He was wearing a knit hat. “Testing, one, two, three,” Marx said into the microphone. “Testing our patience. Testing, four, five, six, seven, eight years of war. Eight years of lies! And we’re live! This park is live! The Vets for Peace are live in Lafayette Park!” (Cheering.)

Code Pink, a women’s antiwar group, was in charge of the pre-noon proceedings. Jodie Evans, Code Pink’s founder, sang “When we make peace instead of war,” to the tune of “Oh when the saints go marching in.” She had on a black hat and a pink vest. She introduced a retired army colonel, Ann Wright, who had resigned her job at the State Department in 2003 because she couldn’t countenance the invasion of Iraq. “I’ll tell you, when Code Pink’s in the house, you know it!” said Wright, to hollers of approval. She pointed across the street. “And the White House knows it!” Wright told us that she had just gotten back from Afghanistan, where the Obama administration was building a $500 million embassy complex. “It’s going to be the largest embassy in the world—larger than Baghdad,” she said.

As a retired colonel, as a former member of the US State Department, and as a citizen, I say that it is our obligation to raise hell! To raise cain! To get these endless wars stopped, and take care of America!

(Big cheering.)

I hurried off to buy some double-A batteries for my audio recorder and when I got back a group called Songrise was performing a heartbreaking a capella version of John Lennon’s “Imagine.” The crowd was bigger now, about eight hundred people. More police had gathered, too.

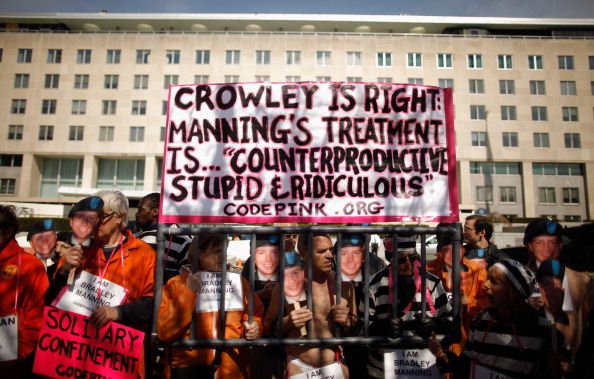

Caroline Casey, another patroness of Code Pink, came on the stage to explain, in a strong contralto voice, what it meant to be advocating peace at the time of vernal equinox and lunar perigee. The culture of cataclysmic dominance was going down, Casey told us, and the culture of reverent ingenuity was rising up out of the cracks. She invited us to spiral the best of ourselves forth into what she called “the memosphere.” She also offered a quote from Hafiz, a Persian poet: “The small man builds prisons for everyone he meets, but the wise woman ducks under the moon and tosses keys to the beautiful and rowdy prisoners.” She tossed a figurative key to young Wikileaker Bradley Manning, in solitary confinement in Quantico, as an agent of democracy, and she tossed a second key to President Obama, to help him see the wrong of Manning’s imprisonment. Obama was himself, she said, “a prisoner of empire.”

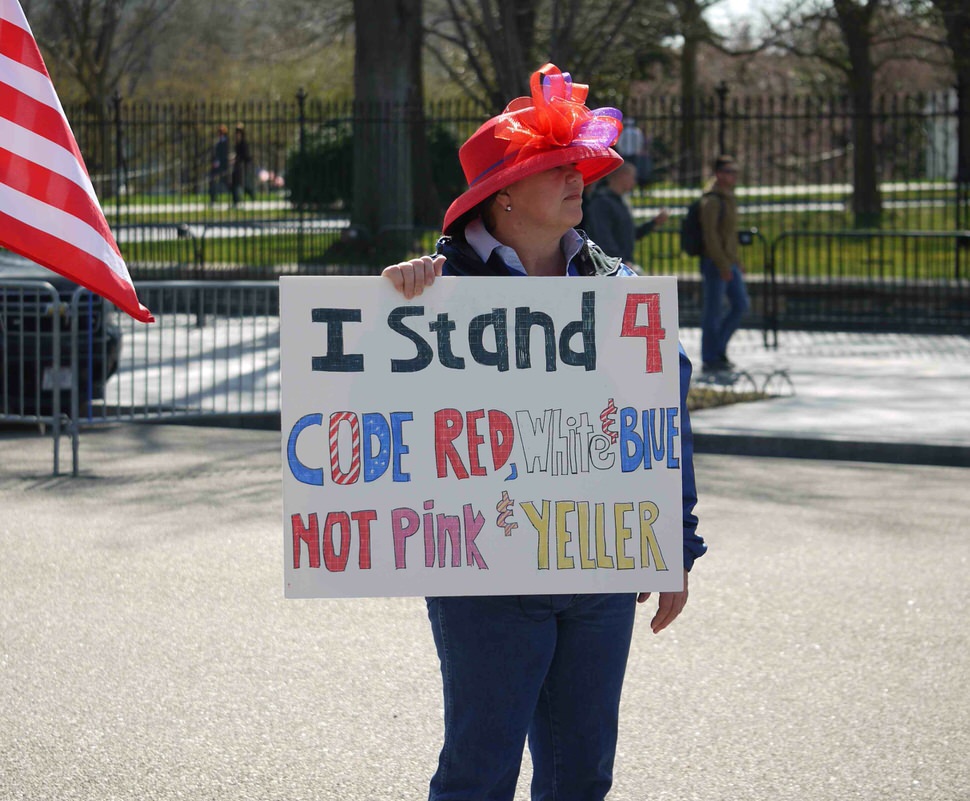

A group of Code Pinkers arranged themselves in a row and opened seventeen pink umbrellas that spelled “BRING OUR WAR $$ HOME.” The crowd was up to about fifteen hundred people by now. A small but committed group of pro-defense protesters—eight of them by my count—were standing out in the street holding flags. Some of their signs seemed to date from another era: CHE IS DEAD GET OVER IT! (held by a woman in sunglasses), and JANE FONDA TRAITOR (held by a man in a black biker jacket). One woman, wearing a gigantic red hat with a red bow, had a sign that said:

Advertisement

I Stand 4

CODE RED, White & BLUE

NOT Pink & YELLER

I went back nearer the platform to hear some of the Vets for Peace speakers. Mike Ferner, who worked in a Navy hospital during the Vietnam War and was the author of Inside the Red Zone: A Veteran for Peace Reports from Iraq, was the master of ceremonies—he was an immediately likeable guy with a thick assymetry of graying hair. He introduced Debra Sweet, director of World Can’t Wait, another antiwar, anti-occupation group that had its beginnings during the Bush era. “We have to take a stand against these immoral, illegitimate wars, and this torture being done in our name,” she said. “I’ll see you in front of the White House!” (Huge cheer.)

Caneisha Mills, who had successfully sued the city of Washington for setting up military-style police checkpoints in poor neighborhoods, said: “The President of the United States, Barack Obama, said that he was going to make a change in the United States. The change that we’ve seen has only been for the worse.” Obama and the government were claiming, falsely, that there was no money for education and health care, Mills argued—and now he was calling for military intervention in Libya, even after Libya announced a ceasefire. “We can see that he only cares about wars of occupation and massive slaughter,” Mills said.

Zach Choate, injured in Iraq, read a Dear Mr. Obama letter, which he then rolled up and put in a pill bottle that had held one of the medications that he’s had to take since the war. “You said you would bring my brothers and sisters home, and they’re still there,” he read. “5,938 of my buddies have died. I’m here today to act peacefully in civil disobedience for my disapproval of these wars.”

I walked around the crowd and took some pictures of a six-foot-long scale model of a Reaper drone. It was painted gray, with wide wings and underwing missiles tipped with red and orange paint, and it was balanced on a pole above our heads. What would daily life be like, it prompted us to ask, if we lived in a country where real drones were flying around high overhead, able to murder by remote control? It would be deeply radicalizing and terrorism-sustaining—obviously.

A woman held a white cloth with lettering on it: “How Many Lives Will You End? How Many Billions Will You Spend? Before You End This Madness?” Meanwhile someone—I missed his name—began talking about the heavy “F.O.G.,” or Forces of Greed, which surrounded us. “President Obama—with his very lovely smile and lovely family, and beautiful rhetoric—sometimes fools people. Now we know that he’s part of the F.O.G. The F.O.G. needs to be lifted.”

A woman shook my hand and said “You are so familiar—have we been arrested together?” I said no, I’d never been arrested.

Ralph Nader was up eventually. He began with some words of sympathy for the victims of the disaster in Japan. Then he said, “General Petraeus said there are fifty al-Qaeda, they estimate, in Afghanistan. Why are we blowing that country apart? Why are we sending our injured and sick home day after day?” Iraq, too—we’d blown that country apart. He quoted a coinage from a recent book called Erasing Iraq: “sociocide.”

Someone near me with yellow dyed hair abruptly turned his back on Nader and said “I’m still pissed off at that son-of-a-bitch about Florida.” Everyone else was clapping, though. How was it, Nader asked, that twenty-five or thirty thousand Taliban fighters, with no air force, no navy, no tanks—armed only with Kalishnikovs and suicide belts and rocket-propelled grenades—were able to resist the most powerful military force in history? “Because,” said Nader, “they have a cause that says ‘Expel the invader.’ Expelling the invader will be forever the cause of anybody in the world who is invaded.”

A duct-taped bucket came around for donations to Vets for Peace, and I stuffed in some money. Then Brian Becker of the Answer Coalition, a socialist group that sponsored some of the biggest peace demonstrations before the Iraq war, tore into the Libyan intervention, which had begun with the launch of a hundred cruise missiles that morning. “We have to learn the lessons that are so crystal clear, as Obama and the Pentagon and France and Britain prepare in the next few hours to start dropping bombs on the people of Libya in the name of democracy,” Becker said. “Let’s know this: Libya is the largest oil producer in Africa, and there’s no possible way that if the US goes into Libya that it’s ever going to come out.” Libya must be the masters of their own destiny, he continued. “We ourselves reject the idea, fed to us once again, that US imperialism, with all of its guns and bombs and missiles, is going to help an oppressed people. The only help we can give to the people of Libya and Egypt and Tunisia and Yemen is to make our own revolution right here!” (Whooping and cheering.)

Advertisement

Watermelon Slim, a craggy country blues singer and Vietnam vet in a camouflage T-shirt, told President Obama to listen up. “Mr. Obama, these wars were George Bush’s wars,” he said. “They are now your wars. I hate to say that, but it’s a fact.” Vietnam vets, Slim said, were now standing at the White House to make known their opposition, just as they’d done back in 1971: “Mr. Obama, you and Mr. Nixon got that in common. We’re paying attention to you. We say, bring our brothers and sisters home, right now!”

Somebody gave me a flyer for the next protest, on April 9th in New York City. Somebody else handed me another flyer, “How is the War Economy Working for You?” It was published by the Veterans for Peace’s Smedley D. Butler Brigade. On it was a quote from Marine Corps General Smedley Butler (1881-1940): “I spent 33 years in the Marines being a high-class muscle man for big business, for Wall Street and the bankers,” Butler wrote. “The general public shoulders the horrible bill in lives, shattered minds, and back-breaking taxes for generations.”

Then Daniel Ellsberg, former Marine Corps company commander and distributor of Vietnam War secrets, was on. He wore a blue blazer and a blue shirt and a sober tie. He was only a few weeks away from his eightieth birthday. He looked great. “Can one person make a difference?” Ellsberg asked. “I would say that without Bradley Manning having released the cables through Wikileaks that inspired the uprising in Tunisia—along with the self-sacrifice of a Tunisian named Muhammad Bouazizi, who burned himself to death in protest against the oppression there—without either of those individuals, Ben Ali, our dictator there, whom we were supporting, would still be there. And Mubarak would still be in Egypt. So one person can make a difference.”

Ellsberg asked us if we knew the names of the two languages of Afghanistan. Almost nobody in the audience knew. “The two languages are Dari—which is eastern Farsi, or Persian—and Pashto,” he said. “In Vietnam, none of us spoke the language, but we knew the language that we didn’t speak—that it was Vietnamese. We’re fighting in a country now where we don’t know the language we don’t know.”

Kings, Ellsberg said, once locked their critics away in dungeons till they were forgotten; the French, he reminded us, referred to these dungeons as oubliettes. Kings also once declared wars without parliamentary approval. Bradley Manning was now in an oubliette at Quantico for revealing America’s war crimes; and the Libyan intervention was, like Korea, an illegal war, waged without congressional approval. President Obama believed that he was in a throne room in the oval office, said Ellsberg, with a crown on his head. It was up to us to knock that crown off. (Wild cheers, including Indian war-cry ululations.)

Ellsberg said: “One of the groups in Tahrir Square, that had been fighting Mubarak for some time, called itself Kafaya, ‘enough.’ We need an ‘enough’ movement: enough to empire, enough to imperial wars, enough to oubliettes.” And he ended with: “This is a good day to get arrested at the White House, and tomorrow at Quantico.” (Mad applause.)

Mike Ferner took the mic. “If you’re planning on getting arrested, if you have any questions, Matt Daloisio is back here behind the stage. Come on up and see Matt.” Once arrested, you had to pay a hundred dollars to be freed, or else you had to appear later in court, Ferner advised. He introduced Chris Hedges, columnist for Truthdig, who said, “If you want to stop terrorism, you must first stop committing acts of terror.” Ferner then gave us guidance on the march. “This is going to be a silent march,” he said. “We need to keep in mind what we’re here for, which is to observe the eighth anniversary of invasion of Iraq. We’re here for a solemn purpose. So let’s be that way, purposeful and thoughtful in our march.” He thanked us for coming and then he said “I’d like to add one personal note to this, which has really been rubbing me raw for some time now.” The people in Afghanistan and Iraq were bearing the brunt of the military aggression, Ferner said, while our cities, our veterans, and our public institutions, were all collateral damage. “Our infrastructure and our public institutions may not be being bombed, but they’re being allowed to slowly rot. And that has got to stop.”

The last speaker was Ryan Endicott, an Iraq marine veteran. He was full of powerful indignation, and he spoke at the top of his lungs. “When we joined the military, we rose our right hand, and we swore to defend the people of this country against all enemies foreign and domestic,” he said. “And the biggest enemies to the people of this country do not live in the sands of Iraq. They do not live in the caves of Afghanistan.” He gestured toward the White House. “They live hundreds of yards away!” (Roar of agreement.)

Endicott said: “We know the realities of these brutal occupations, and we know that these people are not our enemies. The fact is that these wars have cost the American people more than just our lives and our limbs.” The wars had cost trillions of dollars, he cried—trillions that could have gone toward free education and health care, that could have prevented millions from losing their homes, and that could have helped thousands of homeless veterans get off the streets. “And that’s why we’re here today in the streets! The streets that we built! With our sweat, and our tears, and our blood!”

Revolutionary change was possible, Endicott believed: Harvey Milk, Martin Luther King, the people of Tunisia, the people of Egypt, had all made revolutionary change. “We’re going to shut down our workplaces. We’re going to shut down our factories and our schools. And we’re going to tell this government not one more dollar! Not one more bullet! Not one more bomb! Not one more day of US imperialism!” (Cacophony of applause.)

People began arranging their banners and signs and assembling to march. “While everybody is waiting, will you please remove your hats?” said Watermelon Slim. “Except those of us who have chemical gear on.” Then he came to attention. “Present—arms!” He played taps on his harmonica, with a slow mournful vibrato. “We must mourn, we must also show our anger,” he said. “We must also bear this war evenly. Let’s go let them bear some of it, too. Come on.”

Then we marchers set out, led by a World War II vet from the 90th Infantry Division, Third Army. We walked silently around several blocks to the west of the White House (evidently the police didn’t want us to actually circle the White House), and then half an hour later, we massed where we’d begun, in front of the black, sharp-tipped, White House fence.

There were many policemen now: motorcycle cops, park police, horseback police, K-9 police, and sinister-looking SWAT teams in black hats and black uniforms tucked into high black boots. It was a strangely varied festival of police “protection.” They were hauling out segments of a metal crowd-control fence. They locked together the segments, fencing off a large area of public sidewalk and street. (The street, Pennsylvania Avenue, is normally open to public foot traffic and closed to cars.) And then they announced that if you stood on the wrong side of the temporary fence you were going get arrested. The police created, in other words, a potential criminal infraction where there should have been no infraction. For standing on a public sidewalk, in a place where people had strolled undisturbed moments before, you could now be arrested for “disobeying an official order.” I decided that this was ridiculous and that I wanted to be arrested. But after consulting my wallet, I realized that because I’d given forty dollars to Veterans for Peace, I didn’t have enough cash to bail myself out. Next time, I thought.

More than a thousand of us stood against the new barricade, shouting, along with the hoarse-voiced bullhornist, “This is what democracy looks like!” And “Money for jobs and education, Not for Wars and Occupation!” And “Stop these wars! Free Bradley Manning!” And “From Wisconsin to Iraq, stand up, fight back!” And “They say more war, we say no more!” I suddenly felt the rising power of an outraged crowd. It has a different kind of persuasiveness than any verbal argument does. I watched a blind man in a wheelchair, missing several fingers, chanting “US out of the Middle East, No justice no peace.”

A hundred and thirteen protesters were eventually arrested in front of President Obama’s White House that afternoon. (Obama, meanwhile, was down in South America trying to sell F-18 warplanes to Brazil.) The arrests took hours. Someone called out “You’re arresting the wrong people! Arrest Bush I, arrest Bush II, arrest Obama!” One of the women, when she was out of sight in the arrest tent, began a series of blood curdling screams of protest. “Let us see what’s happening,” someone called. As a paddy wagon drove off, someone called out “The jello’s no good in the slammer, don’t eat it.”

In the end the SWAT team had to summon two city Metro buses, in addition to the wagons, to carry off the detainees. Both buses carried ads for breakfast at McDonald’s: “Puts the A.M. Back in Amazing.” The police so parked the paddy wagons and the buses that the crowd couldn’t witness the arrests. As a man with a ponytail was pushed into the back of a paddy wagon, a woman in our crowd read from the constitution, the part about how Congress cannot abridge the right of the people “peaceably to assemble and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.” I applauded her. There was no question that the police were denying the public the right of peaceable assembly.

There were cheers when Daniel Ellsberg, forty years after his arraignment for leaking the Pentagon Papers, was led toward the arrest tent. He turned toward the White House, obliging a policemen who wanted to take his picture. His wrists were zip-corded behind his back. He flashed us a double peace sign from his cuffed hands.

When the arrests were all done, one of the cops collected some “Free Bradley Manning” signs and put them in a garbage bag in the trunk of his cruiser.