One of the oddities of life in Jerusalem is that everyone knows where the future border will run between the Palestinian East and the Israeli West—despite the tiresome insistence of the Israeli government that the city will never again be divided. For example, north of the Old City the line will correspond more or less to what is now called Road Number One, a four-lane road that runs roughly north to south until it reaches the Walls of the Old City, where it turns sharply west just before the Damascus Gate. I drive this road several times a week on the way up to my office at the Hebrew University on Mount Scopus, and the dividing line between Palestinian and Israeli neighborhoods couldn’t be more clear. On the left side of the road, heading north, are the ultra-orthodox neighborhoods Me’a Shearim and Beit Yisra’el; across the street, on the right side of the road, is the well-known Palestinian neighborhood Sheikh Jarrah and the principal Palestinian shopping street, Salah ed-Din. The communities on the two sides of the road receive vastly different levels of investment in education, transport, social services, and other infrastructure.

Despite the government’s continuing attempts to [evict] (http://www.en.justjlm.org/what-is-our-struggle-about) as many Palestinians as possible from East Jerusalem neighborhoods like Sheikh Jarrah and plant colonies of fanatical Jewish settlers in their place, the line is still very clear. It was thus not by chance that on June 1—Jerusalem day, and the forty-fourth anniversary of the reunification of Jerusalem in the Six Day War—the municipality sponsored and largely financed a mass march in favor of further Jewish settlement in East Jerusalem (and, indeed, throughout the occupied West Bank). With police protection provided by the state, tens of thousands of marchers followed Road Number One south and west into Sheikh Jarrah and then into the Old City. The very idea of dividing the city is anathema to those who organized and took part in the march—although most know very well that there is no hope whatever of achieving any settlement with the Palestinians without such a division. The march was clearly meant as a statement of the right-wing goal of asserting and cementing Israeli sovereignty over the entire city by pursuing the settlement project in Palestinian neighborhoods. As it happens, the marchers also called out [aggressive and overtly threatening messages] (http://www.en.justjlm.org/487) aimed at the Palestinian population and at Israelis who support Palestinian independence that should not be minimized or overlooked.

Most of the marchers were young people, and probably a majority of them were settlers. (The police estimate of the turnout was 25,000, almost certainly on the low side; others estimated over 40,000.) For much of the way, this huge crowd was chanting slogans that, I think it’s fair to say, Israelis have never heard at such a pitch—slogans such as “Butcher the Arabs” (itbach al-‘arab) and “Death to Leftists” and “The Land of Israel for the People of Israel” and “This is the Song of Revenge” and “Burn their Villages” and “Muhammad is Dead” (the latter with particular emphasis outside the mosque in Sheikh Jarrah and then again as the march entered the Muslim Quarter of the Old City). It’s one thing to hear such things occasionally from isolated pockets of extremists, or from settlers in the field in the South Hebron hills, quite another to hear them from the throats of tens of thousands of marchers whipping themselves into an ecstasy of hatred. The slogans call up rather specific memories: I couldn’t help wondering how many of the marchers were grandchildren of Jews who went through such moments—as targets of virulent hate—in Europe. Palestinian residents of Sheikh Jarrah and the Muslim Quarter of the Old City watched in horror, but there were no attempts to meet the hatred with violence.

For nearly twenty-fours hours the settler mob maintained a huge, raucous presence in the streets of East Jerusalem, taking particular delight in marching through the Muslim Quarter at 4AM. Some of the marchers threw stones at Palestinian passersby near the Damascus Gate. The police, who largely stood by while this was going on, arrested three activists from Shiekh Jarrah Solidarity and nine Palestinians protesting in Silwan, of whom seven were children, along with a few settlers.

So here you have one vision of the future of Jerusalem—and, sadly, it looks very much as if the current wave of racist hysteria is only gaining strength in Israel. Moreover, as is usually the case with modern nationalism, the political center and the more moderate right show no signs of attempting to hold back the tide. Indeed, a number of members of the government, which is in any case dominated by settler parties, regularly contribute to the inflammatory rhetoric. What’s left of the old Israeli left is fragmented, diminished, and politically ineffectual.

Advertisement

And yet the peace camp is not dead. A joint Israeli-Palestinian initiative is planning a counter-march—under the banner “Marching for Independence”—on July 15 of possibly historic significance. The numbers will be much smaller—maybe 2,000 or so, if the organizers are lucky—but the meaning of the event will certainly transcend the bare numerical count. Something quite new is under way in Palestine. September is getting closer, and with it the possible proclamation of the Palestinian state at the U.N. General Assembly in New York. Even if the United States casts its veto in the Security Council against Palestinian independence— a paradoxical move, given the official and long-standing American support for a Palestinian state in the 1967 borders— the reality on the ground may begin to change.

Many, from Ehud Barak, Israel’s Minister of Defense, down to the grass-roots Palestinian activists I meet in the territories, expect to see in September a Palestinian version of the “Arab Spring.” No one knows exactly what form it will take, but dress rehearsals have already begun—for example on May 15, Nakba Day, when mass demonstrations of Palestinians from Syria managed to break through the fence at Majdal Shams in the Golan Heights. On that same day more than a thousand demonstrators—among them Palestinians, young Israelis, and International supporters—who marched at the Qalandiya checkpoint separating Jerusalem from Ramallah, and were pinned down for seven hours by a barrage of teargas and other aggressive crowd control measures by the soldiers at the checkpoint. Although it received far less attention in the press, it was the demonstrations at Qalandiya that, in my view, most clearly pointed to what lies ahead.

A Mediterranean variant of Gandhian-style mass protest has by now [taken root] (http://www.nybooks.com/blogs/nyrblog/2010/jun/14/unarmed-protest-new-palestinian-approach/) among Palestinian communities in several parts of the West Bank: Ma’asara, Nabi Saleh, Dir Kadis, Na’alin, and Bil’in, to mention only a few. There is by now a clear awareness among many that non-violent resistance is far more likely to be effective against the Israeli occupation than violence; and these days the humane principles of Gandhi and Martin Luther King are frequently and clearly articulated in Arabic by grass-roots Palestinian leaders.

An eloquent [statement] (http://mondoweiss.net/2011/06/bassem-tamimi-to-judge-land-theft-and-tree-burning-are-not-just-your-military-laws-are-not-legitimate-our-peaceful-protest-is-just.html) of the philosophy and method was delivered on June 5 by Bassem al-Tamimi, one of the leaders of the Nabi Saleh protests, at his trial at an Israeli military court for organizing demonstrations. [Al-Tamimi’s text] (http://mondoweiss.net/2011/06/bassem-tamimi-to-judge-land-theft-and-tree-burning-are-not-just-your-military-laws-are-not-legitimate-our-peaceful-protest-is-just.html) will, I am sure, someday be taught in schools, maybe even in Israel; it is remarkably reminiscent of Mahatma Gandhi’s [famous statement] (http://www.4to40.com/history/index.asp?p=MK_Gandhi_Statement_In_The_Great_Trial_of_1922) to a now forgotten British judge in Ahmedabad in 1922, when the judge sentenced him to jail for six years.

Non-violent resistance is also the official policy of the Palestinian government in Ramallah. Salam Fayyad, the Prime Minister, spoke in the village of Bil’in on June 24th, where the non-violent protest sustained by the villagers for over seven years against the appropriation of village lands by the Separation Barrier was finally crowned with some success (the Army has begun to move the Separation Barrier at Bil’in slightly to the west, in partial compliance with an Israeli Supreme Court Ruling from 2007. The village will, however, still lose about a third of its lands to the Barrier): “The results of popular resistance may be slow,” Fayyad said,

but they are guaranteed, and the whole world is with us. This [the success of popular resistance] is something that is inevitable. It’s not over by any stretch of the imagination – this is just the beginning, but it’s a good beginning. It took a long time…[The moving of the Wall] underscores the immense power of nonviolence.

No one would claim that all Palestinian factions have renounced violence, but spokesmen for the government in Ramallah have argued, with some justice, that the recent Fatah-Hamas rapprochement reflects a recognition by Hamas that they have failed and that the non-violent strategy of the moderates is working.

The Jerusalem march on July 15th is another important step. For the first time ever, all of the Palestinian factions that have organized protests throughout east Jerusalem, including the highly effective neighborhood committees and various NGO’s active in Palestine, are joining with Israelis, under the aegis of the Solidarity movement in Sheikh Jarrah, for political action. It’s also important to note that young people are taking the lead. In a way, the march is [expected] (http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/features/empathy-toward-the-palestinian-side-invokes-hatred-and-distrust-1.371874) to mark the triumph of the mode of non-violent protest in Palestinian Jerusalem, in line with what is happening elsewhere in the West Bank.

Advertisement

East Jerusalem, caught between the Separation Barrier and the Green Line, its lands annexed to Israel in 1967, has been demoralized and more or less neutralized politically for the last several years; what we are seeing today is an attempt on the part of the some 300,000 Palestinians who live there to reclaim the political weight that should naturally be theirs. The fact that this is happening in close cooperation with young Israelis from the left is a promising development. For those that have been mobilized, there is clearly a [firm common ground] (http://www.en.justjlm.org/542). The Solidarity website states unequivocally: “There is no choice for anyone advocating an end to Israeli control over the Palestinians other than supporting the only realistic way left to achieve this goal: recognition of an independent Palestinian state.”

Here, then, is the other future for Jerusalem, the alternative to the settlers’ program. On one side, we have a violent, mystically charged racism with its vision of brute domination of one people by another, and of an endgame of perpetual disenfranchisement and dispossession. On the other side, we have the prospect of a free Palestine, with its capital in East Jerusalem, the end of the Occupation, and the realistic hope of an agreement based on compromise and mutuality, an agreement whose details are by now common knowledge and broadly acceptable to a majority on both sides of the Green Line (it is one of the paradoxes of Israeli politics that Israelis consistently elect governments far to the right of their own positions, while polls continue to show that about two-thirds of Israelis support an agreement along the lines everyone knows are feasible). You’d think it would be an easy choice.

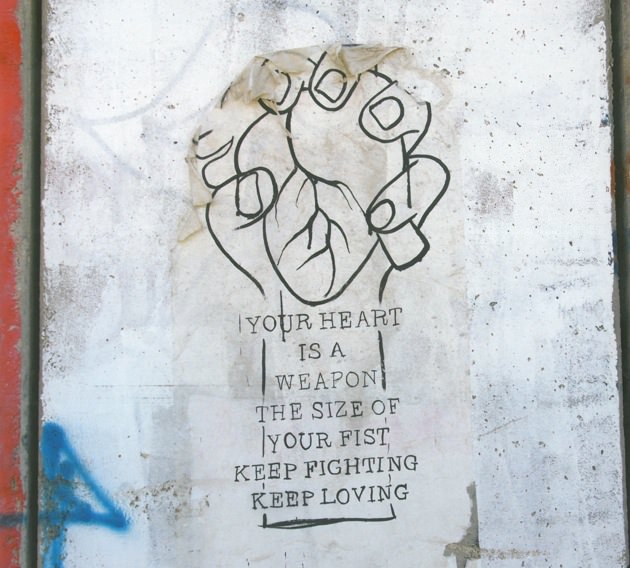

The images by William Parry are drawn from his recent book Against the Wall: The Art of Resistance in Palestine.