Every October, for decades, a group of reporters and photographers from all over the world has gathered in the stairwell of an apartment house in Stockholm, waiting to hear if the poet upstairs has finally won the Nobel Prize in Literature. The poet’s wife, Monica, would bring them tea and biscuits while they stood around—but they would always leave, around lunchtime, as the news came in that the prize had gone to someone else. Annually, the name of Tomas Tranströmer came up, and with every year one felt a growing sense that he would never receive this highest literary honor from his own country.

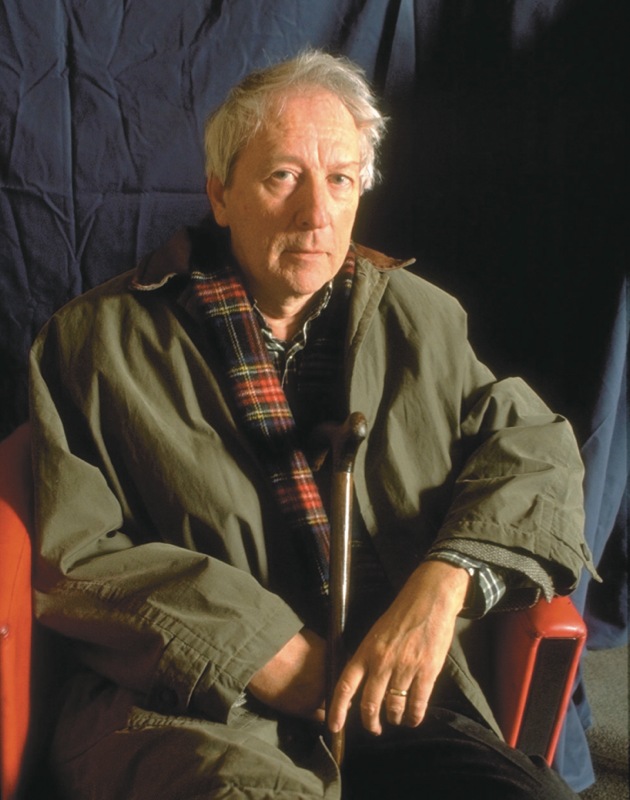

Now eighty, Tomas Tranströmer, who won the prize this year, is not only Scandinavia’s greatest living poet, but also widely regarded as one of our most important contemporary international writers. Born in April 1931, an only child, his parents divorced when he was three years old and he was brought up by his mother within the educated working class of Stockholm: a Social Democratic system infused with the traditional Lutheran ethics of moral compassion and generosity. He took up a career in psychology, working in a young offenders’ institute in Linköping. In 1965 he moved with his wife and their daughters, Paula and Emma, to Västerås, a small town west of Stockholm, where he continued his work with juvenile delinquents, convicts, drug addicts, and the physically handicapped.

It was during this time that his poetry began to reach its full maturity and an international audience. It was translated into over sixty languages and brought him a host of awards. In 1990, however, his life was changed irrevocably by a serious stroke. While his disability did not end his writing career, it did impair his ability to communicate, and the Tranströmers now live quietly in the Södermalm district of Stockholm—near where Tomas lived as a young boy, and overlooking the sea-lanes where his grandfather worked as a pilot, guiding ships through the Stockholm archipelago—and in their cottage on the island of Runmarö, where Tomas spent his childhood summers.

The landscape of Tranströmer’s poetry has remained constant during his fifty-five-year career: the jagged coastland of his native Sweden, with its dark spruce and pine forests, sudden light and sudden storm, restless seas and endless winters, is mirrored by his direct, plain-speaking style and arresting, unforgettable images. Sometimes referred to as a “buzzard poet,” Tranströmer seems to hang over this landscape with a gimlet eye that sees the world with an almost mystical precision. A view that first appeared open and featureless now holds an anxiety of detail; the voice that first sounded spare and simple now seems subtle, shrewd, and thrillingly intimate. There is a profoundly spiritual element in Tranströmer’s vision, though not a conventionally religious one. He is interested in polarities and how we respond, as humans, to finding ourselves at pivotal points, at the fulcrum of a moment.

The following poems are taken from The Deleted World, English versions of poems by Tomas Tranströmer, which will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in December.

Solitude (I)

I was nearly killed here, one night in February.

My car shivered, and slewed sideways on the ice,

right across into the other lane. The slur of traffic

came at me with their lights.

My name, my girls, my job, all

slipped free and were left behind, smaller and smaller,

further and further away. I was nobody:

a boy in a playground, suddenly surrounded.

The headlights of the oncoming cars

bore down on me as I wrestled the wheel through a slick

of terror, clear and slippery as egg-white.

The seconds grew and grew—making more room for me—

stretching huge as hospitals.

I almost felt that I could rest

and take a breath

before the crash.

Then something caught: some helpful sand

or a well-timed gust of wind. The car

snapped out of it, swinging back across the road.

A signpost shot up and cracked, with a sharp clang,

spinning away in the darkness.

And it was still. I sat back in my seat belt

and watched someone tramp through the whirling snow

to see what was left of me.

To Friends Behind a Border

I

I wrote to you so cautiously. But what I couldn’t say

filled and grew like a hot-air balloon

and finally floated away through the night sky.

II

Now my letter is with the censor. He lights his lamp.

In its glare my words leap like monkeys at a wire mesh,

clattering it, stopping to bare their teeth.

III

Read between the lines. We will meet in two hundred years

when the microphones in the hotel walls are forgotten—

when they can sleep at last, become ammonites.

Advertisement

Fire Graffiti

Throughout those dismal months my life was only sparked alight

when I made love to you.

As the firefly ignites and fades, ignites and fades, we follow the flashes

of its flight in the dark among the olive trees.

Throughout those dismal months, my soul sat slumped and lifeless

but my body walked to yours.

The night sky was lowing.

We milked the cosmos secretly, and survived.