Following the disputed reelection of President Mahmoud Ahmadenijad in 2009, the world looked on as tens of thousands of Iranians took to the streets in protest, only to be repressed by force, arrested, or worse. Though there is far less coverage of Iran now—few foreign correspondents are allowed into the country—repression has continued and even intensified since these events, with widespread arrests, purges of university faculty, closure of publications, and a clampdown on political activity. Still, supporters of the Green Movement have not been entirely silenced, as Zahra’s Paradise, a powerful new graphic novel set in contemporary Iran, makes clear.

The novel began its life as a blog by an anonymous Iranian-American activist and an Algerian artist—they call themselves Amir and Khalil—who used fictional characters to tell the story of the crackdown. Through acerbic dialogue and black-and-white comic-book style drawings—sometimes dramatic, sometimes tongue-in-cheek—the authors set out to expose the repressive workings of the state and the ruin it visits on individual lives. The blog was successful enough to be translated into a number of languages, and now it has been released in book form in English.

The story opens on June 16, 2009, in the immediate aftermath of the election protests. A mother, Zahra, is looking for her son, Mehdi, aged 19. Like many other youthful demonstrators, he disappeared during the protests, last seen when headed with his brother to join a demonstration in Tehran’s Freedom Square, wearing a Bob Marley t-shirt. Zahra is assisted in the search by her older son, Hassan, an active blogger and part of the lively Iranian youth scene. Mehdi and Hassan are among the tens of thousands of young men and women who flocked to the banner of the two opposition leaders, Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karrubi. Mehdi is in many ways typical of the young men and women in Iran today who try to carve out for themselves a space in the cracks that have formed in the Islamic regime’s strict political and social codes. He practices karate, listens to Iranian rap, and idolizes the Algerian-born, French soccer player Zinedin Zidane. He was studying for his university entrance exams when he disappeared.

Click on any of the images below to enlarge

Mother and brother begin the search for Mehdi on the evening of his disappearance, and their quest turns into an odyssey. In Freedom Square, where they begin their search, Zahra and Hassan find only the street sweepers collecting the debris left after police and thugs attacked the demonstrators: an abandoned sneaker here, the stains of blood in the shape of a human form there. At the city’s hospitals they find beds full of the wounded— “so many boys and girls Mehdi’s age, as if stricken by a plague,” thinks the mother, Zahra. Revolutionary Guards storm into the hospital to drag the wounded out of their beds and to take them away in sealed minivans. At the gates of Evin Prison, an important-looking official is indifferent to Zahra’s plea for information about her son. Others at the prison gate recall the fate of the Iranian-Canadian photo-journalist, Zahra Kazemi, who died in Evin, reportedly after Judge Mortazavi struck her, causing a brain hemorrhage. “They think they can silence our women, beat our Zahras down or blot out her memory,” a bystander remarks.

Driving to the city morgue, Zahra and Hassan see bodies of executed demonstrators hanging from cranes. Finally, they end up at Behesht-e Zahra (Zahra’s Paradise), Tehran’s vast cemetery, from which the book gets its ironic title (Zahra is also the name of one of the Prophet’s daughters). At Behesht-e Zahra are buried not only everyday Tehranis, but also the “martyrs” of the revolution, the casualties of the eight-year Iran-Iraq war, and now also the victims of the Islamic Republic’s execution squads.

The people that Zahra and Hassan come across in their quest tell them stories: of missing relatives, confiscated property, executions, and the like. Hassan, for example, visits at his home a young man who shared a cell with Mehdi and others at Kahrizak Prison—the Tehran detention center where both male and female prisoners were allegedly assaulted and tortured during the 2009 protests. He describes these horrors: “I was raped! Raped in the name of their God, in the name of their Iran! Raped in the name of their prophet…It is their Islamic republic—not me—that is covered in filth!” Khalil’s drawings reconstruct this event as the young man is remembering them: his interrogators forcing him to face a cell wall; his trousers being pulled down; the document he was forced to sign afterwards, presumably saying he was well treated.

The novel’s drawings often reveal this kind of terrible irony. They represent a distinctly Iranian style of humor, a means of puncturing pretence and power. Iran’s leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, is depicted as the Caliph of an all-male harem, choosing a new favorite among the politicians and clerics who are vying for his attention. The Revolutionary Court is pictured as a Kafkaesque maze of stairs, running upside down and sideways and seemingly going nowhere. Iran’s judiciary is evoked by a huge, gaping set of a mullah’s jaws. Moving stairs and runways, carrying an endless line of the accused enter the jaws from one side; they emerge from the maws of the mullah, after side trips to the torture chamber and the confession room, carrying signs of their prison sentences: “10 years,” “2 years,” “17 years.”

Advertisement

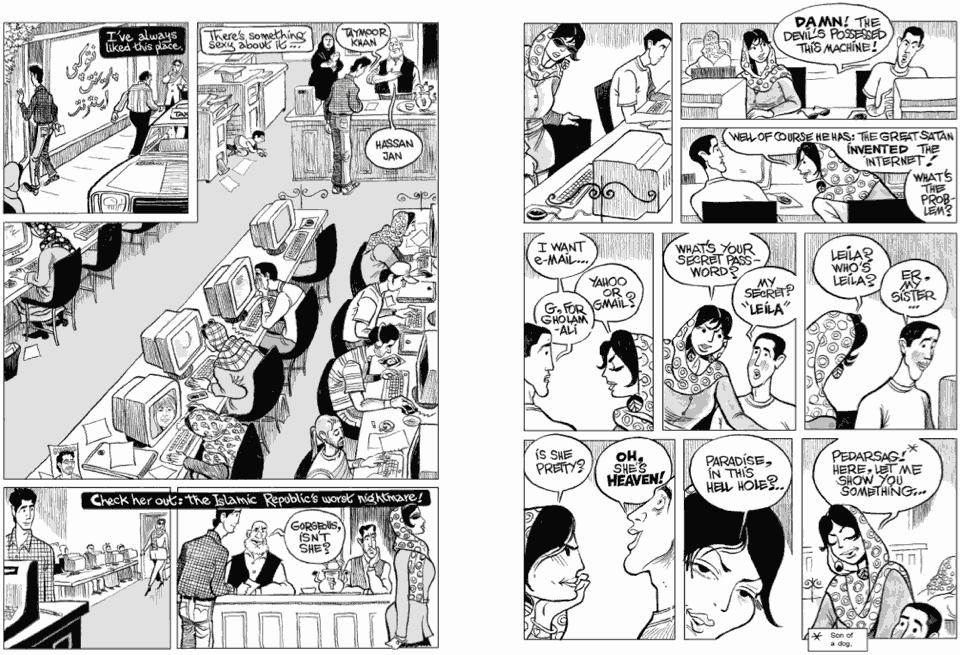

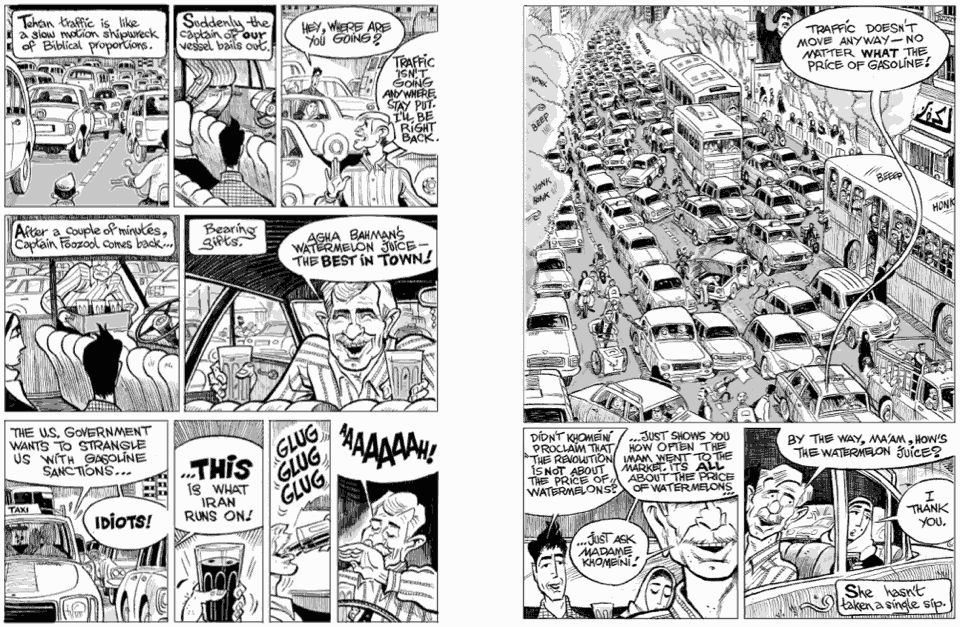

The protagonists of Zahra’s Paradise are in many ways representative types. Zahra is like the thousands of mothers who in Iran today persist in the search for missing sons and daughters and who courageously demonstrate before detention centers and in public parks, and issue open letters to the authorities seeking the freedom of their incarcerated children. Even today, a number of these mothers gather every Saturday in a Tehran park for this purpose, often risking arrest. This gathering is included in the book, and the police are shown dispersing the women. The brother, Hassan, provides an entrée into the world of Iran’s irreverent youth culture: into bedrooms plastered with posters, endless hours on the internet, intense camaraderie and the furtive but easy interaction between men and women in internet cafes. A taxi driver, taking Zahra and Hassan on their ronds, abandons his cab in the middle of Tehran’s perennially snarled traffic to fetch himself and his passengers a glass of his favorite watermelon juice. As the drawing appropriately shows, his absence hardly matters, since the traffic is not moving at all.

Throughout, the authors want to show the ability of people to resist and endure: by helping one another and making common cause. The world of Zahra’s Paradise is, in fact, a world of ordinary people ranged against a cruel regime. The owner of the internet café gives refuge to a demonstrator and later prints without charge a thousand copies of Mehdi’s picture, which Hassan can distribute and plaster across the city. A wealthy and well-connected woman befriends Zahra and introduces her neighbor, a senior and kindly cleric who is able to help her—an act of generosity not uncommon among people in Iran.

The break in the search for Mehdi comes through a chance encounter at an internet café between Hassan and the young and pretty Sepideh, the mistress of a man who we are later given to understand is a senior official, perhaps in the Intelligence Ministry or the Revolutionary Guards. Sepideh takes a liking to Hassan, flirts with him a bit at the internet café and, on leaving, takes a picture of Mehdi home with her. In scenes of enthusiastic love-making between Sepideh and her thuggish lover we see how social taboos are being broken in this supposedly “Islamic” republic. A young middle-class girl feels no compunctions at becoming the mistress of a married official who can keep her in style, buy her expensive clothes and jewelry, and take her on trips to Dubai. But when Sepideh comes across pictures of him among young protesters being brutalized in prison she realizes what he does for a living. She manages to slip to Hassan a data disk of secret files that her lover carelessly leaves behind in their apartment—files that eventually confirm that Mehdi has been killed in Prison.

The intercession of the kindly cleric allows them to retrieve Mehdi’s coffin from the Intelligence Ministry’s section of unmarked graves in Behesht-e Zahra. It is Mehdi’s mother, another Zahra, to whom the authors give the last word. She mourns the death of her son and the death of the Iran and Islam she loves. Addressing her dead Mehdi, she says, “Speak of the end of time, the end of life, speak of the end of Iran, the end of Islam! Speak that the world may know that all of Iran’s sons have died and lie dead in you…I am not Zahra, and this is not my paradise.”

Zahra’s despair is well-founded. According to a United Nations report on Iran that was released in late September, over 300 secret executions reportedly took place at Vakilabad Prison in 2010, and a further 146 secret executions have taken place in 2011. The Committee to Protect Journalists reports that 34 journalists had been detained by the end of 2010. One of them, Mohammad Davari, was sentenced to five years for making a series of videotaped statements by prisoners at the Kahrizak detention center who said they had been abused, tortured and raped. Among activists for women’s rights, Bahareh Hedayat, an activist with the One Million Signatures Campaign (a movement to collect one million signatures on a petition for women’s equality under the law) was sentenced to nine and a half years in prison, for “assembly and collusion against the regime” and for insulting the Supreme Leader and the president.” The list goes on and on and includes jail sentences for film directors, members of the Bahai faith, and human rights lawyers. According to Peace Nobelist Shirin Ebadi, 42 attorneys have been prosecuted by the government since 2009.

Advertisement

In a 13-page epilogue, Zahra’s Paradise lists the names of 16,901 men and women killed by the Islamic republic. Collected by the Abdorrahman Boroumand Foundation, the list resembles the Vietnam memorial, paying homage to the dead through the simple recall of their names. The print is so tiny, you cannot decipher the individual names; but these many pages of fine print cry out their message loudly and clearly.