The photographer Duane Michals, who turns eighty on February 18, pursues a distinctive approach to his medium that seems all the more remarkable today for being so resolutely low-tech. Michals relies only on available natural light, whether he works indoors or out; prefers to shoot in empty found spaces rather than in a studio; and generally favors unmanipulated black-and-white film over digital color—which taken together seems the visual equivalent of producing vinyl LPs in a world of MP3s.

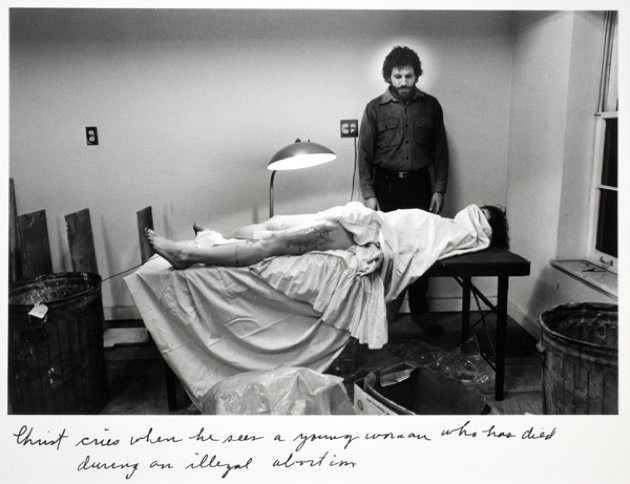

Michals pioneered the use of multi-frame series to create cinematic image sequences as brief as two photos or lengthy enough to fill entire books (of which he has produced more than twenty). These works include the antic “I Build A Pyramid” (1978), in which he constructs a miniature tumulus stone by stone in six shots before the great monuments at Giza, or his haunting sequence “Christ in New York” (1981), a half-dozen modern-dress parables including “Christ cries when he sees a young woman who has died during an illegal abortion.” He has also been a major exponent of adding handwritten texts to amplify the emotional content of pictures, as in his heartbreakingly autobiographical “A Letter from My Father” (1975), which ends, “But then he died, and the letter never did arrive. And I never found that place where he had hidden his love.”

That narrative practice earned the disdain of ideologues who upheld the primacy of the “subjectless photograph” as advanced from the early 1960s onward by the Museum of Modern Art’s longtime photography curator, the influential John Szarkowski. (Nonetheless, in 1970 MoMA gave him a small one-man show, Stories by Duane Michals, though the museum’s press release rather condescendingly described as “an exhibition of evocative mime fables.”)

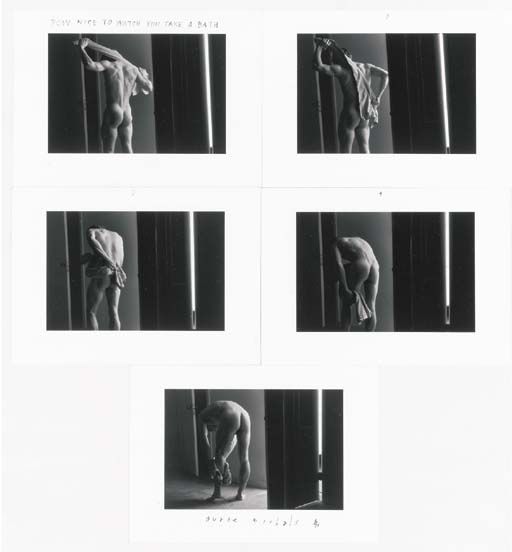

There is an intangible quality about Michals’s photographs that is readily identifiable, regardless of their subject matter. Whether they ponder questions as speculative as the existence of an afterlife—evoked in his seven-part double-exposure sequence “The Spirit Leaves the Body” (1968)—or as basic as the nature of sexual desire—as in the five-frame “How Nice to Watch You Take a Bath” (1986)—all of them encompass a shared spiritual terrain, a timeless realm of pellucid light and preternatural calm, palpably present but also eerily elusive, like a waking dream.

Yet Michals’s most significant contribution may be his championing of an elevated homoerotic alternative to the predominant heterosexual viewpoint of western art. As he writes in his newly released photo-memoir, The Lieutenant Who Loved His Platoon, “Some men worship Venus’ beauty./ Other men worship Apollo’s perfection./ The effect is both the same.” That parity has been fundamental to his aesthetic outlook, and put him at diametric odds with his younger and far more celebrated contemporary Robert Mapplethorpe, who strived to make male homosexuality seem as outré, transgressive, and shocking as possible. Michals, who has lived with the architect Fred Gorree for more than fifty years, is in every respect the Apollonian opposite of the Dionysian Mapplethorpe.

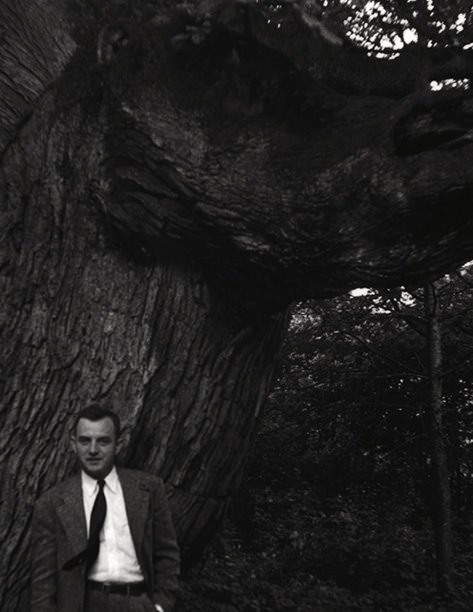

Thus the publication of this quiet crusader’s memoir—which recounts Michals’s own repressed sexuality while in the army from 1953 to 1955—seems particularly timely following the recent revocation of the US military’s preposterous “don’t-ask-don’t-tell” policy. The photographer’s small, illustrated volume picks up the autobiographical thread that he began to spin in his affecting 2003 book, The House I Once Called Home: A Photographic Memoir with Verse. That elegiac visual memory piece revisited the photographer’s childhood in the Pittsburgh exurb of McKeesport, Pennsylvania during the 1930s and 1940s, through pictures of his family’s former residence in a blue-collar neighborhood now devastated by industrial decline. There Michals contrasted recent images of the now-decaying property with views of the same modest interiors shot in better days from identical vantage points—ghostlike pairings that gave an uncanny sense of time passing before one’s very eyes.

Not unusually for a period when there were few if any positive public role models for gays, Michals grew up with only vague intimations of his true sexual identity. As he recalls, “I was in the closet but I did not know that I was in the closet or that there was a closet.” He found a rare moment of clarity as a teenager when he discovered Whitman’s ecstatic paean to male “adhesiveness” in Leaves of Grass, an awakening memorialized in his lyrical 1996 book-length photo essay Salute, Walt Whitman. But for the most part he adhered to the norms of conventional American masculinity.

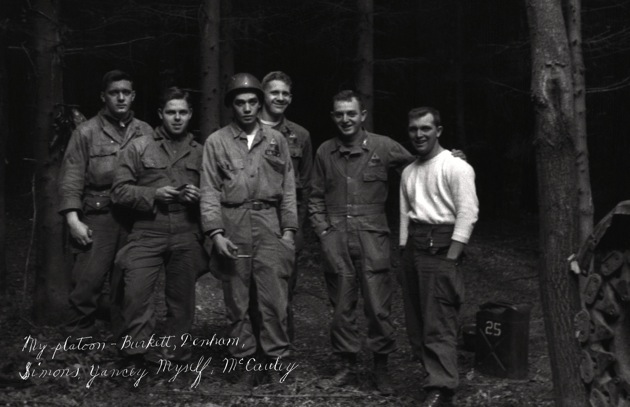

Attending the University of Denver while the Korean War and army conscription were still in frightening progress, Michals signed up for ROTC to avoid being thrown into the scrum of draftees when the inevitable post-graduation call-up came. The college corps’ trainees were guaranteed an instant officer’s commission, and Second Lieutenant Michals was posted not to the Korean peninsula, where hostilities had just ended, but to allied-occupied West Germany, where he was put in charge of a platoon garrisoned at Baumholder, a village in the Rhineland-Palatinate.

Advertisement

During the early 1950s, letters were still GIs’ only direct link with those they left behind, and Michals’s two principal correspondents reflected his still-unresolved sexual orientation. In The Lieutenant Who Loved His Platoon, Michals offers the antiphonal letters that he wrote to his “perennial college date,” Helen McDonald, and to Richard McFadden, a gay high school friend who had moved from McKeesport to New York City—to chart his emerging self-awareness.

With more than a half-century’s hindsight, he writes that these letters reflect

“…the two parallel universes I inhabited. Those I wrote to Helen described observations of the everyday life of the men, the seasons’ constant change, the injustice of rank and command, the prison of duty. There was never suggestion of my burgeoning attraction for my cohorts. Sex was not for polite discussion, and I was taught to be polite. It never occurred to me that I was being duplicitous. Rather it was sin by omission, a strategy of self-defense. The irony is that Helen, the most sympathetic of all people would have been my ally in this kaleidoscopic life. To McFadden, my father confessor, I could describe my daily titillations and petite fears…”

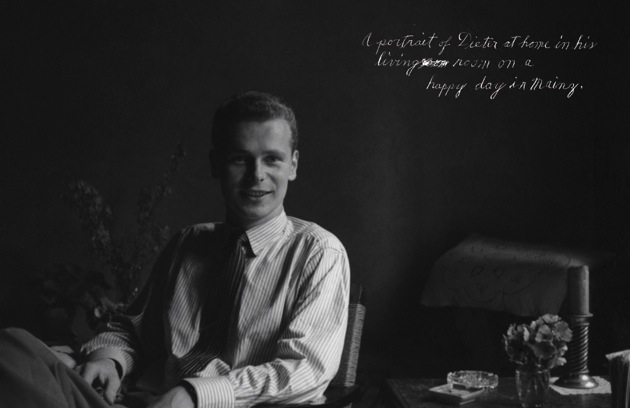

He ruminates about a number of personal matters, but erotic awakening seems to run just beneath the surface of his consciousness. On occasion, that subterranean stream bubbles to the surface, as in a letter to McFadden that reports in touching detail Michals’s flirtation with a handsome nineteen-year-old German named Dieter, whom he photographed in his parents’ gemütlich living room on what Michals’s handwritten caption recalls as “a happy day in Mainz.”

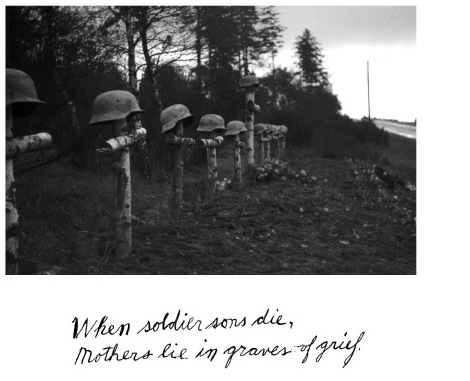

Like many another GI in occupied Europe, but with infinitely more talent, Michals further documented his Army experience through pictures taken with a nifty German-made camera. The results as reproduced in the new book show his expertise and essential style to be firmly in place a full decade before his first gallery show in New York in 1963. Announcing several of his major themes is Michals’s diagonally composed photo of a row of birchwood crosses topped with Wehrmacht helmets, under which he writes, “When soldier sons die, mothers lie in graves of grief.”

Yet even his group snapshots of the uniformed men under his command—posed against stands of trees that prefigure the photographer’s affinity for dappled Corot-like boscage as a backdrop for arcadian visions of youth and beauty—rise above banal army souvenirs and reveal the emergent artist’s eyes beginning to open in more ways than one.

The Lieutenant Who Loved His Platoon: A Military Memoir was recently published by Antinous Press.