Earlier this month, the South African artist William Kentridge and the American historian of science Peter Galison were on hand in Kassel, Germany to install and introduce The Refusal of Time, the work Kentridge created for the international exhibition dOCUMENTA (13). The work is, in part, the result of an extended series of discussions between Kentridge and Galison about the history of the control of world time, relativity, black holes, and string theory.

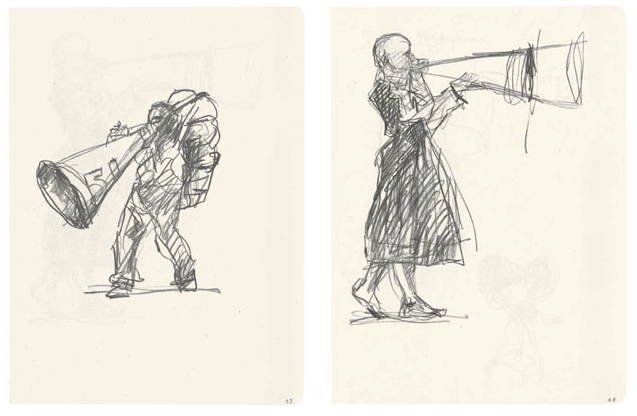

In the installation, five films are projected on three walls of an industrial space near the Kassel train station. A large wooden structure with moving parts—it resembles something like an accordion and an oil rig combined—occupies the center of the room; this is the “breathing machine (elephant).” Intermittent sounds of Kentridge speaking and music (most memorably tubas and singing) are transmitted through silver megaphones, one at each corner, each with a different soundtrack. The projections are sometimes in sync, but usually they run contrapuntally: a row of metronomes mark time at different speeds; Kentridge repeatedly walks over a chair; maps of Africa flip past in an old atlas; a torn-paper figure performs arabesques; more torn black paper, blown by a current of air, gathers to form a coffee pot, is blown away, becomes a coffee pot again; strings and stars animate a charcoal sky; twin Kentridges move almost in unison; vignettes set in Dakar (1916) and the clock room in Greenwich (1894) end in an explosion and a climactic serpentine dance; Duchamp’s inverted bicycle wheels spin in negative like an animated Rayograph.

For the dramatic finale, Kentridge has created one of his signature shadow processions, inspired by the view from Plato’s cave—but with a new ending: silhouetted figures dance, stagger, or march relentlessly left to right, across the three walls, before they are finally consumed by a black hole. In the coda, a “pneumatic man,” wearing a bouncy inflated suit, playfully dances with a woman, leaving the door open for a more hopeful verdict.

A few days before the opening, I met with Galison and Kentridge at the Mercure hotel in Kassel to talk about the ideas and themes that inspired the work.

The Room of Failures

Meg Koerner: You had both been working on the subject of time for many years. How did The Refusal of Time come about?

Peter Galison: We were both fascinated by this late nineteenth-century moment when technologies wore their functions on their sleeve, so to speak; they hadn’t sunk their structure into chips and black boxes. One of the things that has made working together so appealing has been that we were both interested in this notion of embodied ideas, of very abstract things worked out in the material world.

Meg Koerner: Can you tell me what an “embodied idea” would be in your case?

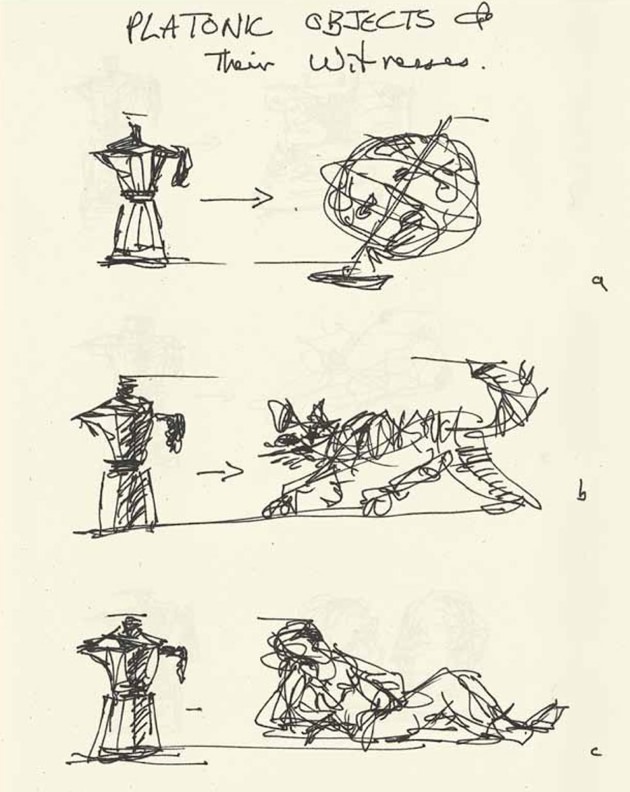

William Kentridge: There are certain objects which I have come to as someone making drawings, objects that meet the drawing half way. If you take an old Bakelite telephone, its blackness is already half way to being a charcoal drawing. But more than that, once you are drawing it, there is a set of associations that come from old, manual, mechanical switchboard telephones. If you think of a switchboard, there is a cord that would connect the caller and the receiver, and the representation of it looks like a black line drawn across the holes of the switchboard. In my case, of drawing and animation, something that is now perhaps invisible—connecting people across phone lines across continents—is rendered in a very visible way, and may even be a description of an obsolete process. It is not so much being fascinated with the ideas of the late nineteenth century, but that it was still such a “visible” era, in a way in which an electronic era is not. Even if one is talking about contemporary phenomena, very often an older representation is a better way of drawing it.

MK: How did your collaboration work?

PG: We would trade stories back and forth.

WK: I’ll tell you a story. A German scientist, Felix Eberty, had come to understand that the speed of light had a fixed speed and wasn’t instantaneous, and he worked out that everything that had been seen on earth was moving out from earth at the speed of light, so instead of having space as a vacuum, he described it as suffused with images of everything that had happened on earth. You would just have to be at the right distance from earth to be at the right moment to see what had happened in the archive—to see anything that had happened—so if you had to start 2000 light years away, in his terms you could see the crucifixion. If you were 500 light years away, you could see Dürer making his Melancholia print, which is 500 years old now.

Advertisement

I was intrigued with the idea of space full of this archive of images that was spreading out. I thought of that in terms of a ceiling projection with all these images…[But] it was jettisoned because it was very complicated in terms of the physical projection. How would you see it? Would everybody have mirrors to look at the ceiling to look from down below (which I had done before)? At one stage we had a whole Room of Failures, which was all the things that didn’t work, which we still could have done.

Dickens’s Elephant

PG: I went to the archives in Paris and I found that there was a system of pumping time pneumatically under the streets of Paris, and I found a map of where the pipes went. Sending air through a copper pipe was a way to jar a clock at a distance, to set it. Vienna and Paris had similar systems. This idea of pumping time, even the idea of it is funny, because we think of time as the most abstract thing that is connected to mortality and fate and the very predicate of history and yet here it is being pumped underneath the streets of Paris.

WK: So Peter tells me that story and I think, right, in Kassel, there was the famous Joseph Beuys honey pump, where he pumps honey around Kassel as a kind of social cohesion idea—I think that was his metaphor—so I thought, let’s have a literal pump. We’ll have a compressor and we are going to pump compressed air, and we are going to send it into two tubas. And we spent months trying to make an artificial embouchure, with compressed air and rubber lips and controlling valves, but each time we just got a terrible loud fart from the tuba, and nothing more controllable than that. That went into the Room of Failures, the embouchure, but the tubas remained as a basis of an important part of the musical vocabulary of the piece.

I bought two beautiful tubas which would have been in the room of failures had we done that. One of them is being used by the tuba player at the live performance in Amsterdam. What remains of that is the tuba in the music, and that big machine in the installation, the “elephant,” as a kind of generator of the energy of the piece.

The “elephant” comes from Dickens’s Hard Times, where he talks about the industrial machines in the factory in the nineteenth century. He talks about them “moving up and down, like the movement of the head of an elephant in a state of melancholy madness.” Endlessly, just moving up and down. The machine actually did have a head, but it became a bit too literal. It has to do with the relentless nature of industrial society.

Drawing Time

PG: One theme we were very determined to do while working together was the imperialism of the late nineteenth century. Even the idea of the colonial powers stringing these cables across the globe at a moment when they didn’t have electric lights, while they were creating a machine that literally encircled the earth, that went across the oceans and up into the mountains, to try to send these signals to coordinate clocks. There was something tremendously moving and disturbing about this. The British were using their cables to direct their armies and move their ships and to direct anti-colonial wars. They were cutting the French cables and reading the messages so that they would be able to anticipate them in conflict.

WK: For me it was also a question of what is it in us that so naturalizes—as if they had always been there—a hundred-year history of coordinated time zones and the division of the world into segments?

PG: “Greenwich Mean Time” rolls off the tongue. It seems natural: of course Greenwich is the center. But the French understood perfectly well, for example, that who controls the zero of longitude, the zero point of time, controls something about the mapping of the world and its symbolic ownership, as well as the practical aspects of using admiralty maps to run the world’s shipping. They wanted it somewhere else, and there were big battles.

The guy who tried to attack the Greenwich Observatory in 1894 was Martial Bourdin, a French anarchist. The bomb went off prematurely and he was killed. This formed the basis for The Secret Agent by Conrad. Then the Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski, obsessively read Conrad; he wrote in the midst of his bombing campaign that he read it twelve times. So you have this movement from an attack in history, to a short story, then back to….another terrorist. This back and forth between fiction and history is very intense.

Advertisement

WK: The history of this attempt to blow up the Greenwich Observatory turned into the five short silent films that you saw. They were paper sets, made with time constraints: three hours to draw a set and then film for two hours, and then redraw the next one and film for two hours, and draw on top of repaint and put on a different clock.

MK: Your drawings themselves, the way we see them going through stages that leave a trace behind, embody some of the ideas in The Refusal of Time.

WK: The drawings have a sense of time spent on them, of the erase, redraw, erase, redraw, which is one of the ways of the actual material manifesting the idea. In the process of moving your hand from one side of the table to the other, you have to take on trust its temporal existence, that it used to be here and now it is over here. There is nothing, when you look at it, that says it was there. But with animation, there is a way of erasing and drawing and erasing and drawing, that there is a ghost trace left. In the paper, you see that passage of the movement of the hand, which is of course also the passage of time, given by the material itself rather than an affect added.

The Meaning of Life

MK: Some of the material in The Refusal of Time installation appeared in your Norton Lectures at Harvard this spring. How are they connected?

WK: The sixth Norton lecture took the process of making The Refusal of Time as an example of what the lectures had been talking about: of thinking through material, of allowing the impulses of an image or a piece of work to hold sway and see where they led. Live music was allowed to come into the lecture form at the end of the sixth lecture. The lectures, which started with Plato, end with a black hole. Even though we weren’t starting with Plato in The Refusal of Time, the shadow procession came back as well, and it also ends with a black hole….The image you see at the end, those white holes going down and down, that’s the roll from a player piano. It is both music and information.

PG: One of the debates of modern physics is whether information disappears in a black hole….There is a giant black hole in the middle of our galaxy, and eventually everything will end up in it. Will there be something left?… The side that wants to believe there is something left behind seems to have won, because of the development of string theory. It means that all of the information that falls into that hole would leave something on the surface—a kind of holographic image of the thing that had fallen into it. If that is so, then some trace of memory remains.

MK: At one point in the final Norton lecture, you asked the great question, why become an artist? And by the end of the lecture, we were sitting there, amazed, thinking, is he going to tell us the meaning of life?

WK: The main thing I have always thought about that I forgot to talk about in the lectures was Freudian repression. That can’t have been just by chance.

MK: What was it — what repressed idea did you forget to talk about?

WK: About what is this manic need to circle round and round the studio forever, to be working and making? This is always what it used to be about and I had forgotten about it. It is about trying to keep this massive depression away. It is about this black darkness descending.

A Black Hole

MK: Is The Refusal of Time about avoiding death?

WK: It ends up there. It starts with: Is a black hole the end of time? As Peter was saying, that is one of the questions that physicists consider. But as soon as you say, right, let’s start having things disappear into a black hole, it is an immediate jump to that being, as it were, a metaphorical description of death. Is any trace left when you are gone? Is there any information, attributes of you that still float around the edge? So it is both from the psychological, or the lived sense of, what is the balance between the finality of death and the continuation of attributes of people afterward?

PG: We can’t live forever, but we can hope that some small trace of our existence might somehow survive. In the black hole debate one side contended that it truly was an end to all things, a portent of the final stage of the universe. The other desperately wanted to prove that somehow all the information swallowed up would survive—coded far beyond easy recognition to be sure, but there nonetheless. And in the black hole battle, in this ultimate refusal of the end of time, there is something that struck me as so evocative that I hoped it could be wound into our story.

WK: So that became clear, that one of the elements of the project was black holes, and there was a procession going into the black hole.

MK: You’re in it, right?

WK: I am in it, eating soup.

An illustrated essay about the work, William Kentridge & Peter L. Galison, The Refusal of Time, is available in the dOCUMENTA (13) series, “100 Notes – 100 Thoughts,” published by Hatje Cantz.