As we contemplate the horrific damage caused by Hurricane Sandy, the world of design may seem remote from our most immediate concerns. Yet the urgent needs that follow large-scale catastrophes—the need for shelter, clean water, alternative sources of power—can be particularly conducive to creative solutions. I recently observed that breakthroughs in architecture and industrial design have emerged during wartime; now a remarkable new exhibition in Oslo shows that the same can hold true for natural disasters as well.

Presented by Norsk Form, the Foundation for Design and Architecture in Norway, Design Without Borders (the title is an obvious nod to Médecins Sans Frontières) presents realistic mock-ups of fourteen problem-solving design initiatives—ranging from post-hurricane relief to land-mine removal—in Norsk Form’s DogA exhibition space, which occupies a cavernous turn-of-the-twentieth-century power station in Oslo. For example, a life-size replica of a post-disaster shelter features insulated walls made from empty plastic beverage bottles stacked and held in place with chicken wire within wooden frameworks.

According to Leif Verdu-Isachsen, who organized the exhibition and edited its engaging catalog with Truls Ramberg,

After a natural disaster, we have about a two-week window of opportunity in which to engage the global public before its attention shifts elsewhere, so what we do has to be implemented very quickly. Furthermore, we know that on average these shelters will need to be used for about three years before permanent housing can be built, so the combination of rapid assembly and relative durability is essential.

Putting contemporary design at the center of humanitarian crises, the Norsk Form approach is a notable change from the way the discipline has been viewed in recent decades. Philip Johnson founded the Museum of Modern Art’s design collection in 1932 to promote useful objects that accorded with his concept of industrial design as an art form. That idea was typified by his Machine Art exhibition (1934), which presented airplane propellers and circular ball-bearing housings atop pedestals like works of found sculpture, and for decades thereafter, MoMA’s imprimatur signified that an object could be both beautiful and practical. During the 1980s, however, opportunistic marketers and complicit journalists began to place an increasing emphasis on the celebrity of consumer-goods designers.

Ubiquitous totems of domestic status like Michael Graves’s eponymous tea kettle of 1985 and Philippe Starck’s Juicy Salif citrus squeezer of 1990, both manufactured by the Italian firm Alessi, gave high-style product design an increasingly precious aura. That trend, in turn, propelled the idealistic young designers of Norsk Form to seek ways to radically reconceive modern design and go beyond the rote production of more and more consumer fetish objects.

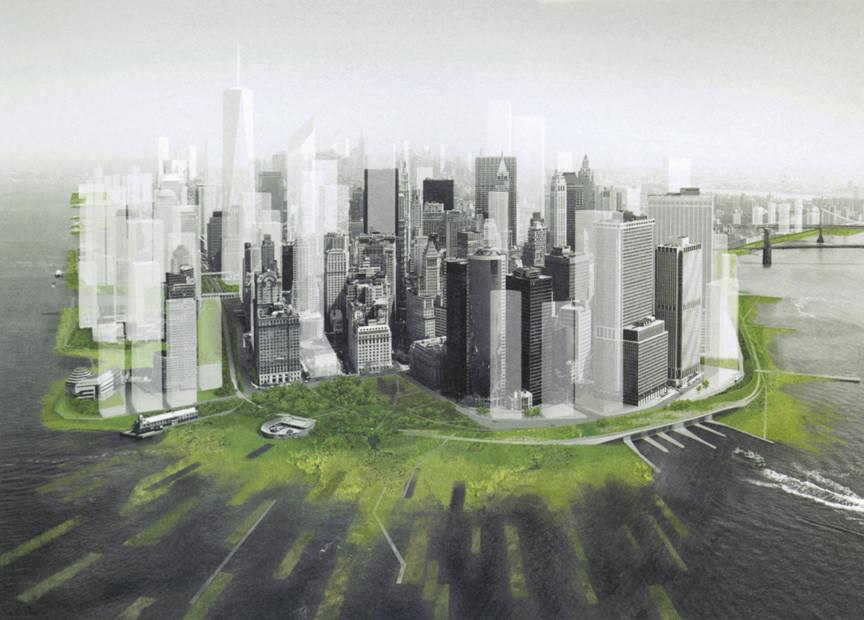

That alternative vision makes Design Without Borders: Creating Change one of the most thought-provoking demonstrations I have seen of the power of design to address vital humanitarian concerns. To be sure, there have been similar initiatives elsewhere, as documented in the Museum of Modern Art’s admirable 2010-2011 exhibition Small Scale, Big Change: New Architectures of Social Engagement, which surveyed nearly a dozen such projects on five continents, all prompted by the same desire to ameliorate living conditions in the developing world. And eerily prescient of the storm surge that engulfed much of the perimeter of New York last week was the 2010 MoMA exhibition Rising Currents: Projects for New York’s Waterfronts, which asked architects, engineers, and landscape designers to come up with ways to reconfigure the Manhattan shoreline to deal with rising sea levels.

However, Norsk Form’s approach differs from that of other development-through-design groups. After identifying a problem in urgent need of remedy—for example, emergency housing for hurricane victims in Guatemala, safer means of land-mine disposal in Mozambique, or eradication of sewage-borne disease in Ugandan slums—the Norwegian collaborative sends designers to gather crucial information about local attitudes, political conditions, and other issues that could bear upon the successful implementation of a project. Then, once a scheme is put in place, Norsk Form brings local designers and community organizers back to Norway for further training to ensure their efforts will be sustained in the long run.

To be sure, some artifacts that have emerged from Norsk Form enterprises are handsome enough to merit inclusion in the MoMA design collection. The lightweight-blue-plastic-mesh protective body armor devised for land-mine removal in hot climates has been nicknamed “the Armadillo” for its resemblance to the segmented carapace of the New World mammal. In the six years since it was perfected, this torso shield—which lowers core body temperature by one to three degrees and increases worker efficiency by 10 to 15 percent—has won over users who are reluctant to wear heavier, hotter protective clothing, an omission that can result in needless injuries or fatalities.

Advertisement

Other objects in the exhibition may be less prepossessing, but their impact can likewise be immense. The Ecological Urinal is an ergonomically contoured plastic funnel that can be attached to the large jerry cans that are among the most ubiquitous objects in Third World communities without running water or easy access to fuel oil. In the slums of Kampala, Uganda’s largest city, there is on average only one toilet per thousand inhabitants, with the result that huge amounts of human waste run through open sewers, seep into the ground water, and pose a constant menace to public health. Norsk Form’s low-cost solution—each urinal costs about forty-five cents—is typical of the group’s understanding of how economic incentives can encourage widespread adoption of its proposals.

In partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which is sponsoring a natural fertilizer plant outside Kampala, Norsk Form conceived a scheme in which the jerry cans filled with urine (which breaks down into its component enzymes within three days) are bought from slum-dwellers so that the urine can be processed into plant nutrients and sold to local farmers. The proceeds from this transaction (small by Western standards but not to poor Kampalans) are an inducement to keep this new mini-economy in motion.

Other ingenious projects include MamaNatalie, a birthing simulator that resembles a Snugli baby carrier but allows midwives to prepare through role-play for complications such as breech deliveries and umbilical-cord entanglements with the aid of a lifelike plastic “baby” manufactured by the Norwegian firm Laerdal Medical, which makes widely-used CPR training dummies. Norsk Form estimates that grassroots training with MamaNatalie and the training videos that accompany the obstetric device could save 250,000 lives in developing countries over five years.

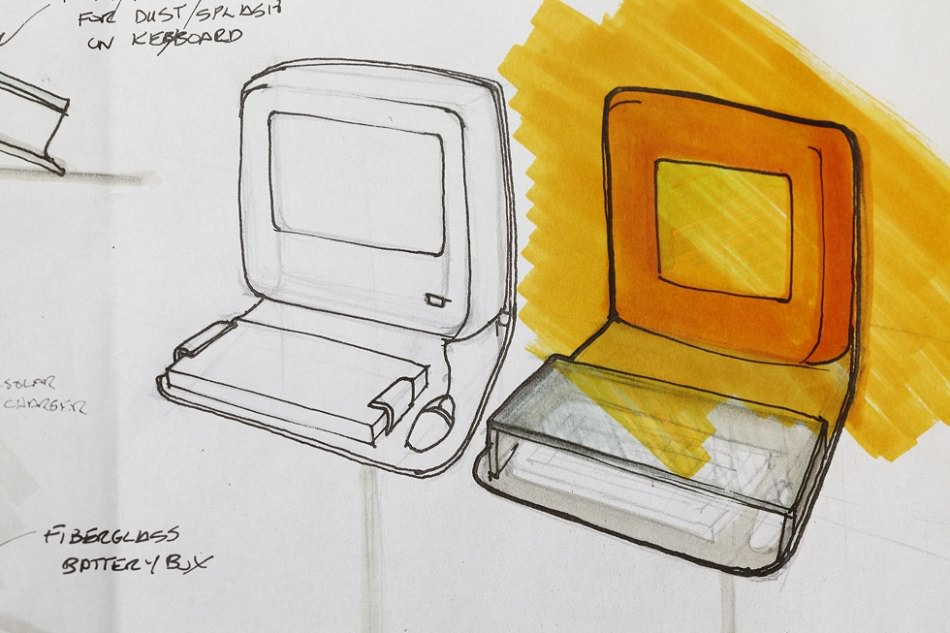

The old adage “Beauty is as beauty does” has never seemed more inspiringly realized than in “Design Without Borders,” and its clear, widely-applicable prescriptions deserve an equally wide audience. While many of the featured projects are clearly aimed at the developing world, the continuing power outages and evacuations caused by Hurricane Sandy in New Jersey and New York City suggest that such design solutions could be equally valuable in dealing with our own crises. A project that has allowed Ugandan villages to set up hundreds of self-sustaining computer centers using solar power, for example, might suggest an innovative way for Western businesses to avoid losing days or even weeks of work to power outages. Norsk Form is seeking an American venue for this illuminating exhibition, and one can only hope that some prescient institution in this country will seize the opportunity to help spread the good word about these latter-day Norse heroes.

Design Without Borders: Creating Change is on view at DogA, the exhibition space of the Norwegian Foundation for Design and Architecture in Oslo, Norway, through December 2, 2012; the catalog can be purchased through the Norsk Form website. The catalog Rising Currents: Projects for New York’s Waterfront, from the eponymous 2010 exhibition, is available from the Museum of Modern Art in New York.