The lost wolves of New England have been on my mind lately, as winter settles into the woods below our house and the lives of the local predators—the hawks and owls and the raucous coyotes—are increasingly exposed among the bare-leafed trees. Wolves have not been welcome in our woods for a very long time. Among the first laws instituted by the Puritan settlers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630 was a bounty on wolves, which Roger Williams, who fled the colony for its religious intolerance, referred to as “a fierce, bloodsucking persecutor.” Extermination of the New England wolf is widely believed to have been completed two centuries later; according to the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, the gray wolf has been extinct in our state since about 1840.

Occasionally a wolf that has ranged wide of its natural habitat wanders into our neighborhood, presumably crossing the border from more hospitable Canada. In the fall of 2007, a male gray wolf went on a rampage on a farm in Shelburne, a half hour to the north of where we live in Amherst, slaughtering over a dozen sheep before he was shot by an unidentified gunman and subsequently examined by the astonished local authorities. “When it comes to wolves, never say never,” Peggy Struhsacker, a Vermonter and wolf expert with the Natural Resources Defense Council, told Fox News at the time, perhaps alluding to Farley Mowat’s popular account of his own adoption by Arctic wolves, Never Cry Wolf.

By the mid-nineteenth century, our New England sages were already lamenting the loss of wildness in both landscape and society, and invoking wolves rather than eagles as a sort of national icon. In his gnomic epigraph to “Self-Reliance,” Emerson admonished his countrymen to

Cast the bantling on the rocks,

Suckle him with the she-wolf’s teat;

Wintered with the hawk and fox,

Power and speed be hands and feet.

Thoreau expanded the allure of a Romulus-and-Remus education in the wild:

It is because the children of the empire were not suckled by wolves that they were conquered & displaced by the children of the northern forests who were.

Thoreau added, as though throwing down the national gauntlet, “America is the she wolf today.”

New England, and southern Vermont in particular, have had a crucial part in both the idealization of wolves and in their ruthless destruction. Rudyard Kipling settled in Brattleboro, where his wife was from, in 1892, and wrote The Jungle Book there, inventing, amid the wolf-less Vermont hills, the beguiling story of a native child named Mowgli, raised (and suckled) by a family of wolves in the forests of India, just as Emerson (a particular favorite of Kipling) and Thoreau had imagined American children should be raised. “Now, was there ever a wolf that could boast of a man’s cub among her children?” asks Kipling’s Mother Wolf.

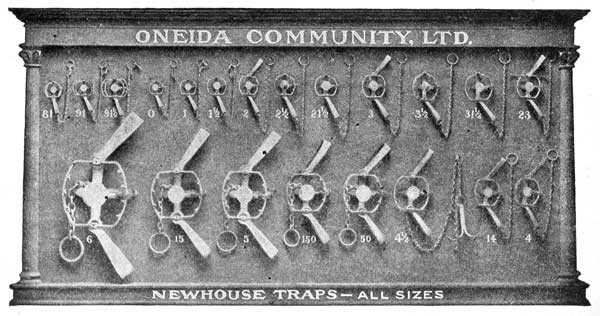

The Brattleboro native John Humphrey Noyes (1811-1886) imagined a very different human society based on “free love” (he originated the phrase) and communal property. Kicked out of Putney, Vermont, for transgressing local moral codes, the utopian socialist Noyes established the Oneida Community in upstate New York, hoping that agriculture would keep his followers alive. Industry, and specifically animal traps designed by a Noyes adherent named Newhouse, proved far more lucrative. Wolf and bear traps were produced at Oneida beginning in the 1850s and soon dominated the market, as free love and wolf hatred proved compatible with sales pitches. The Newhouse Trap, according to one advertisement, “going before the axe and the plow, forms the prow with which iron-clad civilization is pushing back barbaric solitude, causing the bear and beaver to give way to the wheatfield, the library and the piano.”

Oneida traps were widely used both in New England and in the American West, where strychnine inserted into buffalo corpses virtually wiped out the wild wolf population in the lower forty-eight states, except for a remnant few hundred in Minnesota. The Endangered Species Act of 1973 led to the still controversial reintroduction of wolves in areas such as Yellowstone National Park. Just last week a much-loved wolf wearing a tracking collar, which identified her as 832F and the alpha female of the Lamar Canyon pack, was killed, legally, by hunters in Wyoming after she unwittingly strayed just beyond the protective borders of the park.

I have learned a great deal about the systematic extermination of wolves from a beautiful and heartbreaking book called The Lost Wolves of Japan by the environmental historian Brett Walker, who seeks “to explain why one species—our species, Homo sapiens—has worked so tirelessly to destroy another.” Walker points out that before Japan began its rapid modernization during the last quarter of the nineteenth century—under pressure from American forces and with the help of American experts, many of whom came from New England—wolves were considered sacred: “Grain farmers worshiped wolves at shrines, beseeching this elusive canine to protect their crops from the sharp hooves and voracious appetites of wild boars and deer.”

Advertisement

Beef was considered the proper staple of a modern nation, however. With the introduction of so-called “industrial farms” for breeding horses and cattle, especially in the northern island of Hokkaido, wolves were re-categorized as evil predators, and Japan created “a culture of wolf hatred.” So efficient were the Japanese, with guns and traps and strychnine, that the last Japanese wolf was killed, near the beautiful ancient capital of Nara, in 1905, the same year in which the upstart nation won the Russo-Japanese War and took its place among the beef-eating world powers.

Our little town of Amherst has an intimate link to all these developments. The best-known figure in the modernization of Hokkaido was William Clark, who led the Massachusetts Agricultural College (now the University of Massachusetts Amherst) and also, at the invitation of the Japanese, founded Sapporo Agricultural College (now part of Hokkaido University), where he built barns for horses and vulnerable cattle modeled on Amherst prototypes. Like his friend and Amherst neighbor Emily Dickinson, Clark had a gift for memorable words. Leaving Hokkaido in 1877, he reportedly admonished his students, “Boys, be ambitious,” words known to every Japanese schoolchild. (According to some sources, what he actually said was “Boys be ambitious for Christ.”) The boys of Japan and New England were certainly ambitious in exterminating their wolves. It would be more ambitious still to restore them.