Romans knew that the timetable for the papal conclave would be a quick one when the three sets of vestments prepared for the new pontiff—in small, medium, and large sizes—had already disappeared from the display window of Gammarelli, the ecclesiastical tailors, on Friday, March 8. The three white wool satin cassocks had appeared on March 4, along with one scarlet capelet, the mozzetta, trimmed in white ermine, versatile enough for one size to fit any aspiring pontiff, a single pair of red kangaroo-leather shoes in a medium size and a white moiré silk zucchetto, the pontifical skullcap. Though they are loaded with Christian significance, many of these articles of clothing actually have a far more ancient pedigree.

Those red shoes, for example—which the pontifex emeritus has now given up in favor of a more ordinary brown pair from Mexico—may symbolize the blood of Christian martyrs. But when red shoes were the height of fashion in Etruscan Rome, that is, five hundred years before the birth of Jesus, they designated the wearer as an aristocrat, someone who could afford leather that had been colored with the most expensive dye in the Mediterranean, Phoenician “purple”—which was actually scarlet red. (It was produced by scoring the bodies of molluscs and ranged in color from blue to red, with red the most prized shade.) The leather itself came not from kangaroos, of course, but from the Chianina cattle, who came to Italy together with the Etruscans and provided the ancestral form of Florentine beefsteak.

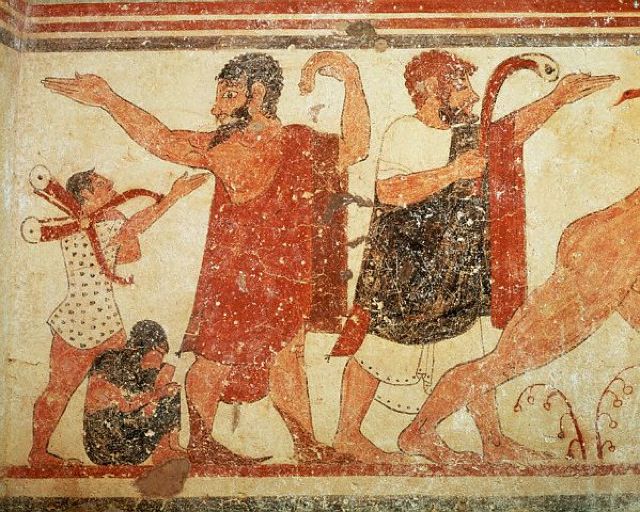

Can it be coincidence that shoemakers like Maurizio Gucci of Florence and Salvatore Ferragamo of Campania and Florence came from places with strong Etruscan connections? A tomb painting from the Etruscan city of Tarquinia, executed perhaps around 530-520 BC, shows several mourners in elegant pointed boots. The people portrayed in this “Tomb of the Augurs” may well have had close connections with Rome, where the ruling dynasts were named Tarquinius, and the tyrant-slayer Brutus, credited with founding the Roman Republic a few years after this tomb was decorated (509 BC), was actually a Tarquinius on his mother’s side. When Roman patricians sported red shoes in subsequent centuries, they were simply carrying on ancestral tradition. With the red shoes went a red-striped robe, again in Phoenician purple—a wide stripe for members of the Senate, a narrower stripe for the second-rank aristocrats known as horsemen, equites. After the coming of Christianity, the tradition of wearing red passed from the Roman Senate to the “Sacred Senate,” the College of Cardinals. Cardinal red, in fact, is Roman senatorial red, derived from Phoenician purple (or a cheaper—but not cheap—substitute called cochineal, made by grinding the shells of beetles).

The pope also inherited an ancient Roman priestly title, Pontifex Maximus, this too, almost certainly passed down from the Etruscans, along with Etruscan priestly paraphernalia like the folding chair we see a servant carrying in the Tomb of the Augurs. A crooked staff called the lituus (one of these also appears in the Tomb of the Augurs) eventually turned into a symbolic shepherd’s crook for Christian pastors, but only long after it had been used by Etruscan priests called augurs to divine the future by scrutinizing the heavens and the flight patterns of birds. Even the zucchetto, a word that means “little squash,” may owe its stem not to botany, but to the bizarre headgear worn by the ancient Roman priest of Jupiter, the flamen dialis; an alternative title for popes during the Renaissance was “Jupiter the Thunderer.”

Today the Pope is rarely seen under the canopy known as the umbraculum, but that honorific sunshade symbolizes his office during the sede vacante. The umbraculum, too, first appears in Etruscan times, shielding aristocrats from the sun’s rays—as in China, umbrellas seem to have been invented first to keep away the sun rather than the rain. Even the idea of the conclave, the locked-in gathering, has a kind of Etruscan antecedent. On the sarcophagus of a woman named Hasti Afunei from Chiusi, the underworld spirit Vanth carries a torch to light the way for the soul of the deceased and a key to unlock the gates of Hades. The doorkeeper for the Sistine Chapel is more soberly clad than Vanth, but she is a close relative of Michelangelo’s devils in the Last Judgment on the Sistine Chapel wall. (Michelangelo, of course, was a proud Tuscan—that is, Etruscan.)

Annibale Gammarelli and Company only claim to have been tailoring for priests since 1798, but it is tempting to think that an ancestral Gammarelli produced the sumptuous red robe of Vel Saties, augur of Vulci, two dozen centuries earlier. If nothing else, Vel’s tailor was clearly a kindred spirit.