How can the most architecturally innovative part of the United States also be such a thoroughgoing urban mess? Los Angeles can boast, among other showpieces, Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall of 1989–2003, Charles and Ray Eames’s own Case Study House Number 8 of 1947–1949, and Raymond M. Kennedy’s Grauman’s Chinese Theater of 1926–1927—to name three of my favorite landmarks there. And yet LA is also a highway-strangled, traffic-choked expanse of artificially lush desert with no discernible organizing principle save for the allées of palm trees that filmmakers reflexively use to establish a recognizable sense of place.

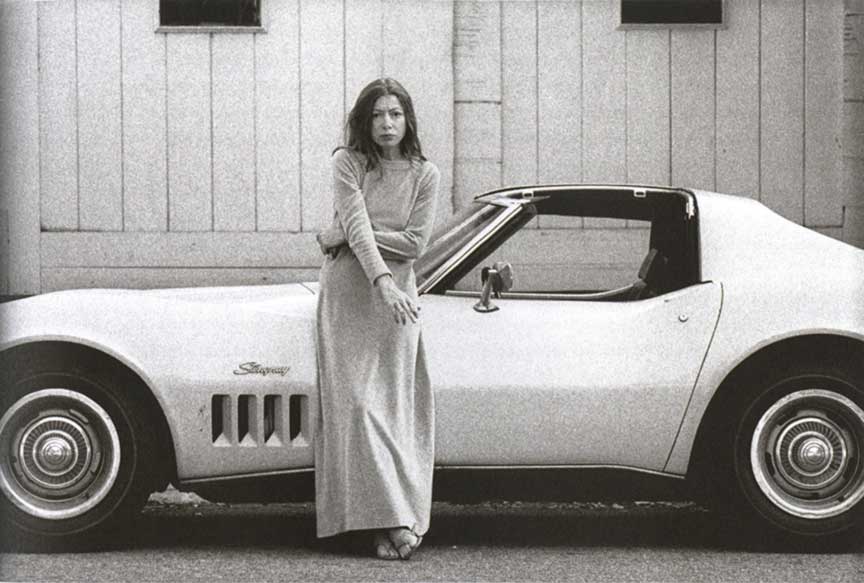

Describing the persistent incoherence of Los Angeles, Dorothy Parker famously jibed that it was “seventy-two suburbs in search of a city.” More sympathetic observers like the British architectural historian Reyner Banham have long pointed out that it’s futile to apply traditional standards of urban design to this 469-square-mile sprawl, which they see not as a dysfunctional megalopolis but as a prophetically modern phenomenon. Yet to comprehend why the City of Angels remains so enduringly weird to outsiders, it is not architectural specialists but rather imaginative writers—from Nathanael West and James M. Cain to Evelyn Waugh and Joan Didion—to whom we must turn.

This spring and summer, two complementary exhibitions in Los Angeles seek to bring the unfathomableness into focus. The first, “Overdrive: L.A. Constructs the Future, 1940–1990,” which is at the J. Paul Getty Museum through July 21, explores how the city emerged through fitful initial development, explosive postwar growth, and a distinctive built legacy. The second, “Never Built: Los Angeles,” which opens at LA’s Architecture and Design Museum on July 13, examines a stunning array of unexecuted projects to show why the city didn’t become something else.

Both surveys are accompanied by extensively illustrated catalogs, offering non-Angelinos a chance to reframe their imagined views of this quintessentially quirky conurbation. Of the two publications, Overdrive addresses a broader variety of topics, including architectural education, postwar tract houses, the role of the local aerospace industry in promoting modernism, and (perhaps too extraneously) cultural interchanges between LA and both Latin America and the Pacific Rim. Neither Overdrive nor Never Built Los Angeles rehash the already-familiar story of the Case Study House program, that ambitious midcentury attempt to show average homeowners how good design costs no more than a developer’s mass-produced ticky-tacky.

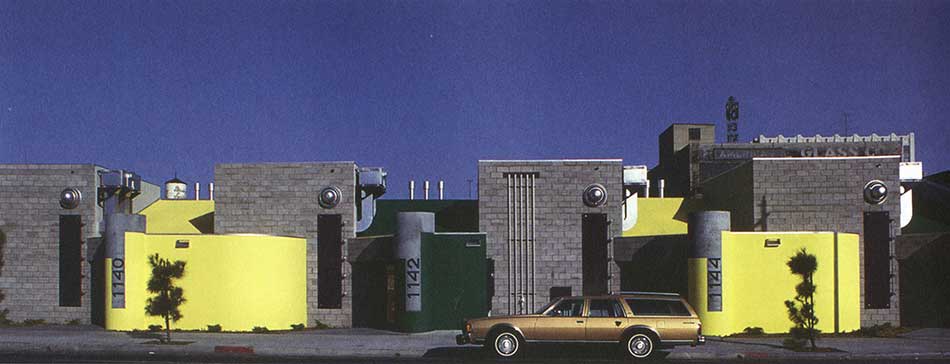

The vernacular commercial architecture of the LA region has long been a favorite of populist historians such as the architect Charles Moore, whose endlessly diverting The City Observed: Los Angeles (1984), written with Peter Becker and Regula Campbell, examples of what is known as Googie architecture, named for a now-defunct West Hollywood coffee shop designed by John Lautner, an architect of flamboyant Space Age proclivities. One particularly welcome chapter in Overdrive, by Vanessa R. Schwartz, traces the planning of Los Angeles International Airport during the 1950s and 1960s. Several large firms participated, but this huge undertaking centered around the work of Paul R. Williams, the African-American architect who was responsible for a number of movie star homes and the Polo Lounge at the Beverly Hills Hotel, and who dreamed up the Jetsonesque LAX Theme Building, with its flying-saucer restaurant suspended beneath two intersecting parabolic arches.

Of particular interest in Overdrive is Stephen Phillips’s essay “Architecture Industry,” which examines the so-called LA Ten, an informal group of young, experimentally-minded architects; Thom Mayne, who contributes a rueful foreword to Never Built Los Angeles, is today the best-known of them. The Ten were inspired by the city’s gritty aesthetic:

Characterized by an expansive network of manufacturing, industrial, and warehouse communities situated alongside trucking facilities, ports, rail yards, freeways, waterways, and endless parking lots, Los Angeles’s infrastructure supports a sublime manufactured landscape that has had a powerful influence on the cultural imagination of a generation of postmodern architects.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the Ten came together around Frank Gehry, their older mentor and hero, whose corrugated-steel-and-chain-link-wrapped bungalow of 1977–1978 in Santa Monica spawned an entire school of architecture that includes Eric Owen Moss’s numerous industrial building conversions in Culver City from 1988 onward and Mayne’s Caltrans District 7 headquarters of 2001–2004 for the state highway department in downtown LA. Their preference for indigenous industrial materials, casual detailing, and unfussy finishes has become the architectural lingua franca of the contemporary art world.

Along with Mayne, Gehry himself took a spiffed-up version of the Ten’s tough-guy aesthetic to LA’s desolate downtown with his Disney auditorium, but attempts to give the city’s notional center something like the round-the-clock vitality of New York’s Times Square or London’s Leicester Square have failed time and again. The few parts of Los Angeles that sustain a viable pedestrian nightlife—like Westwood Village, with its busy movie theaters and restaurants near the UCLA campus, and Los Feliz, a hipsterish enclave closer to downtown—still present a problem, for most visitors need to drive there in order to walk around.

Advertisement

Perhaps the saddest part of Never Built: Los Angeles is devoted to some of the many unimplemented master plans aimed at producing the high-density throngs that can today be found at Anaheim’s Disneyland (which Moore unironically called the best example of urban planning in the region). However, these ill-fated projects also suggest that regardless of what was proposed, the city was destined to face the same sorts of demons because of its fatal rejection of alternatives to the automobile.

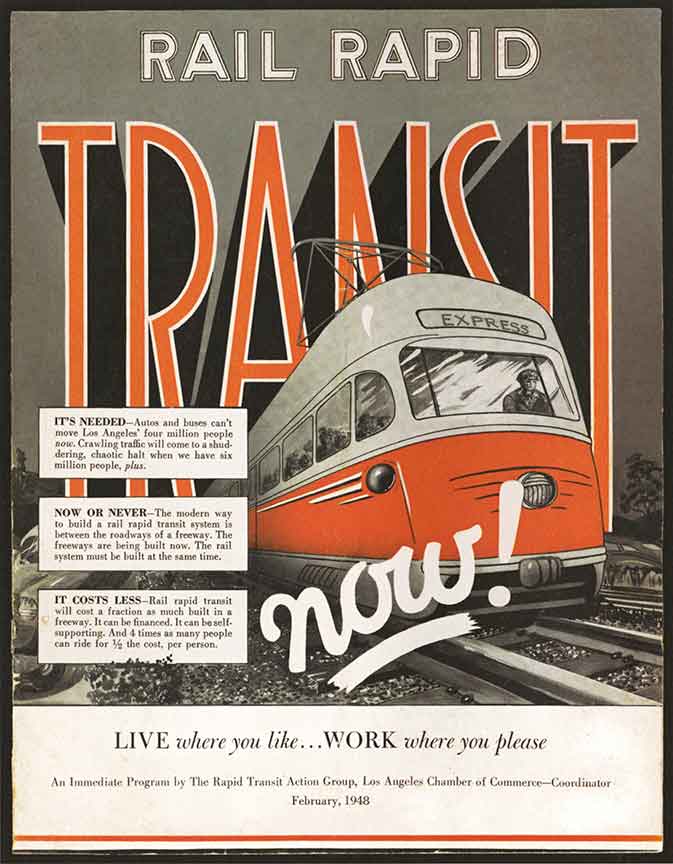

A rueful inclusion in the Getty show is the cover of the Rapid Rail Transit report from 1948, which endorsed augmenting LA’s Gordian highways with comprehensive mass transit. “The modern way to build a rail rapid transit system is between the roadways of a freeway,” the white paper urged. “4 times as many people can ride for ½ the cost, per person.” Not only were such sensible recommendations ignored, but within fifteen years the Los Angeles Railway, a trolley system that served a vast north-south swath of the region, would be dismantled, in part because of what many believe to have been a conspiracy by General Motors and others to kill off the competition.

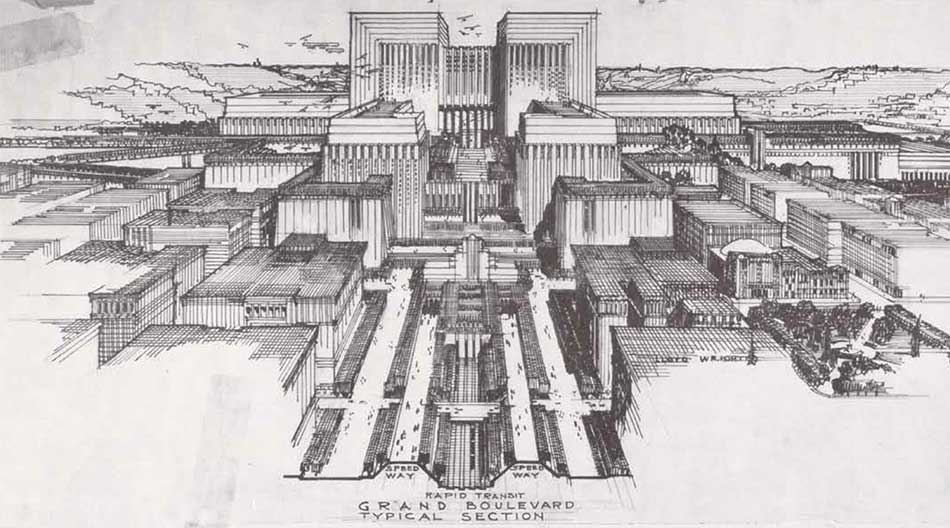

Yet things could have turned out worse. One of the most arresting images in Never Built: Los Angeles, the extensively illustrated catalog accompanying the show, is a 1925 proposal for a civic center on downtown LA’s Bunker Hill by Lloyd Wright, the not-untalented architect son of Frank Lloyd Wright. This impossibly grandiose scheme—seemingly informed by the Italian Futurist architect Antonio Sant’Elia’s visionary La Città Nuova (1914), Walter L. Hall’s celebrated Babylon set design for D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1918), and the pre-Columbian monuments that inspired the elder Wright’s California buildings of the 1910s and 1920s—lacks any sense of ecological appropriateness.

As Overdrive makes clear, all sorts of vernacular architectural responses to LA’s dominant car culture arose to meet the particular demands of an increasingly mobile population, with innovative forms such as the drive-in restaurant, the drive-through car wash, and, heaven forefend, the drive-in church (the most distinguished example of which was Richard Neutra’s Garden Grove Community Church of 1959–1968). Not for nothing did Moore organize his study of the city’s architectural features into a series of “rides” to be seen from a car window.

In a country where personal “freedom” invariably trumps the common good, this pair of enlightening but cautionary surveys reminds us of the late and much-lamented Ada Louise Huxtable’s ever-timely admonition that “Any city gets what it admires, will pay for, and, ultimately, deserves.”

“Overdrive: L.A. Constructs the Future, 1940–1990” is on view at the J. Paul Getty Museum through July 21 with a catalog edited by Wim de Wit and Christopher James Alexander. “Never Built: Los Angeles” will be on view at LA’s Architecture and Design Museum from July 28 until September 29; the accompanying volume, by Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin with a foreword by Thom Mayne, will be published by Metropolis Books.