One of the healthier phenomena of the past decade has been the fresh attention that what were once the two largest American classical recording companies have been paying to their back catalogues. When these century-old labels—the former Columbia Phonograph Company, founded in Washington D.C. in 1888, and the one-time Victor Talking Machine Company, formed in Camden, New Jersey in 1901—joined forces to become SONY Masterworks in 2004, we were finally permitted to hear complete or near-complete collections of recordings by many of the leading artists of the twentieth century.

It is not only the superstars who have received encyclopedic treatment. The recordings of Enrico Caruso, Arturo Toscanini, Arthur Rubinstein, and Jascha Heifetz had long been available, pretty much in their entirety and at exorbitant prices. But now we can immerse ourselves in the recorded legacies of pianists Van Cliburn, Gary Graffman, Byron Janis, Leon Fleisher, and the star-crossed William Kapell, as well as the spectacular Chicago Symphony Orchestra recordings by Fritz Reiner and even comprehensive presentations of relative, still active, “youngsters” such as pianist Murray Perahia and cellist Yo-Yo Ma.

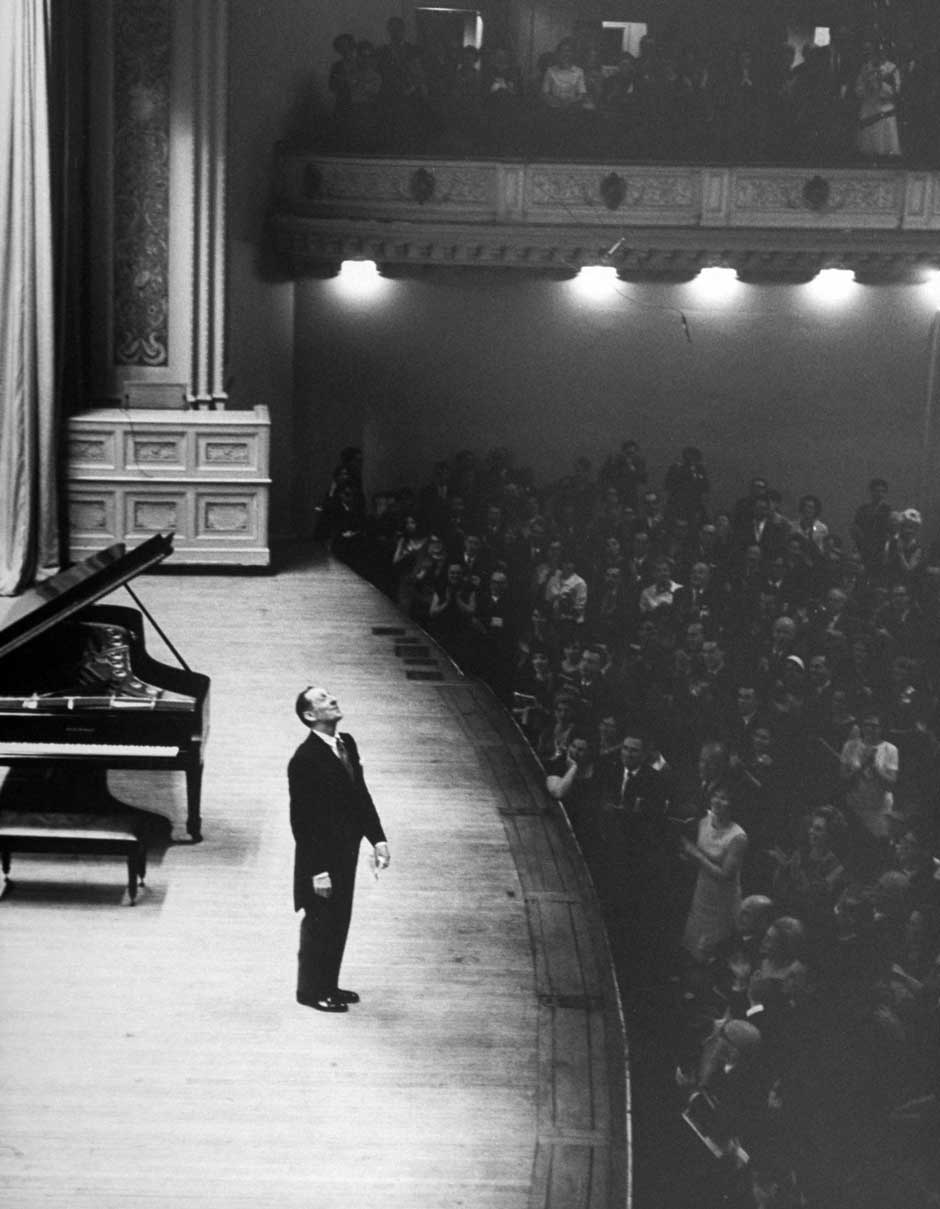

One recent set of particular interest is dedicated not only to a single artist but to that single artist playing in a single hall, some thirty hours of music collected as Vladimir Horowitz Live at Carnegie Hall. Issued with the support and cooperation of the hall itself, this doesn’t include every performance the pianist played there (he made his house debut in 1928, more than a decade before the invention of magnetic tape would have permitted such sustained recording) but offers extensive documentation of performances ranging from 1943 through 1976. There is also—at last!—a DVD restoration of the 1968 telecast of “Horowitz on Television,” which has not been officially seen since CBS turned over an hour of precious prime time to it almost half a century ago.

That evening changed a lot of lives, as households tuned in across the country to see and hear one of the most celebrated of all pianists (remember that there were only three networks in 1968—and no video stores or Netflix) and Horowitz never again played to an unsold seat. Watching it again after so many years, one notes Horowitz’s seeming ease and charm, his 300-watt smile, his remarkably flat fingers (the bane of so many music teachers), and, above all, his command of dynamics. Chopin’s dark and crushingly difficult Polonaise in F-sharp Minor combines a long, brutal quasi-minimalist study in motoric reiteration with a tender chromatic intermezzo that somehow seems to prefigure Edward Grieg in its simple sweetness. And finally, when you don’t think the piano can possibly get any louder, the playing any more savage and furious, Horowitz (as they might have said in This Is Spinal Tap) “turns it up to 11.”

It is a style of playing that will never be to everybody’s taste. I miss the melancholy songfulness of the later Rubinstein recordings, the kaleidoscopic poetic imagination of Alfred Cortot, the purity and formal rigor of Maurizio Pollini, among others. There are times when Horowitz pecks and pokes at the piano in a way that shatters melodies into what seem so many shards of glass. Nor does he seem comfortable with the depth and expanse of a work such as the Schubert B-flat Sonata; both performances here explore the piece skittishly instead of with the sustained abundance of trust and full-heartedness that we admire in the best renditions, like those of Clara Haskil, Maurizio Pollini, or, more recently, Leif Ove Andsnes.

And yet there are surprises throughout—a marvelously propulsive performance of the Beethoven Sonata in D (Op. 10, No.3), for example, that epitomizes the exact moment when the composer was moving from Haydn-like classicism to his own epical understanding of romanticism. Samuel Barber wrote his only Piano Sonata for Horowitz; it will likely never be played more brilliantly than it is here. The set also includes three movements of Barber’s lesser-known “Excursions,” a solo piano piece that mixes modernism and American vernacular music.

For me, the real discovery is some music by Dmitri Kabalevsky—Horowitz made a famous disc of the Soviet composer’s Sonata No. 3 in his youth, but the Sonata No. 2 and some preludes are unreleased, fresh experiences, and could almost be described, strange as it sounds, as light music from Soviet Russia. It is music that will naturally call Prokofiev and Shostakovich to mind, but if there is less passion and profundity than we find in the best works by these men, there are also fewer sardonic smirks; one suspects that Kabalevsky, at least, may have been able to laugh without wincing.

It has been said that Horowitz was at his best when before an audience; I’ve never entirely believed this, especially since he made some of his best recordings in his East 94th Street living room, during a long sabbatical from the stage that lasted from 1953 to 1965. When he returned to public performance—of course, his first concert was at Carnegie Hall—he sold out the house in two hours, only to begin the program with some spectacular clinkers in the Bach-Busoni Toccata Adagio and Fugue. I remember friends telling me of their shock at the time—and, indeed, the “live” performance that was issued on what was then Columbia Masterworks edited these errors out. Since 2003, the original version has been available and it is a moving experience, as Horowitz recovers almost immediately and follows up with a deeply musical recital.

This set, complete with a three-hundred-page book with essays in English, French and German, and pictures and promotional material from throughout Horowitz’s career, is a model of scholarship and respect. It is also, at its best, very exciting indeed. Horowitz-manes will have to have it, of course, but even those with a more measured interest will find something to admire, as the old master plays, again and again, in the concert hall he loved most.

Selected recordings of Vladimir Horowitz at Carnegie Hall

“Vladimir Horowitz Live At Carnegie Hall” is available now.