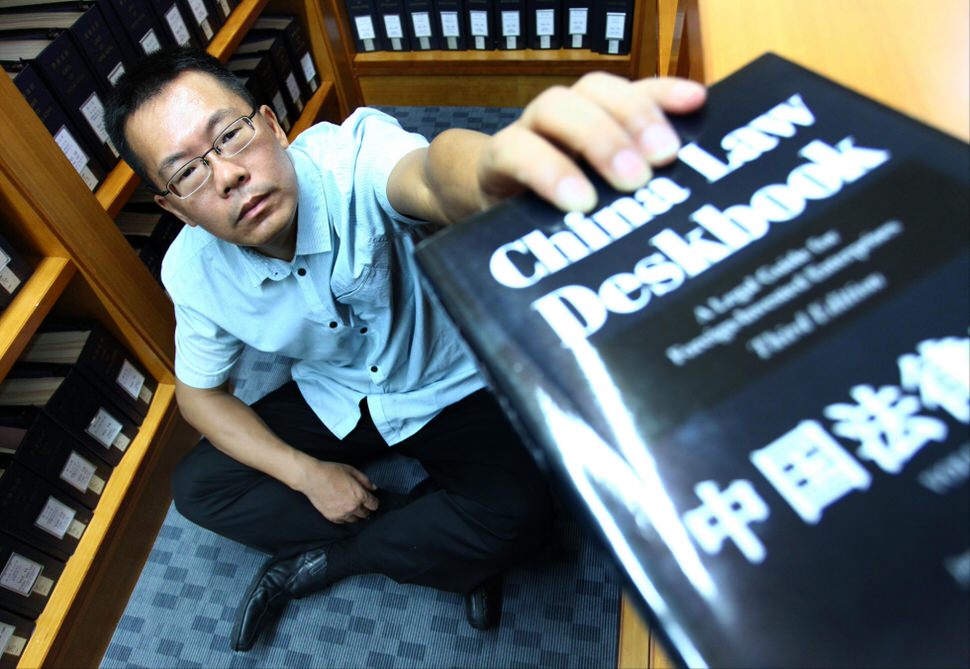

Teng Biao is one of China’s best-known civil-rights lawyers, and a prominent member of the weiquan, or “rights defenders,” movement, a loosely knit coalition of Chinese lawyers and activists who tackle cases related to the environment, religious freedom, and freedom of speech and the press. He came to national attention in 2003 when he and two other young Peking University law students successfully petitioned parliament to end the “custody and repatriation” law that gave police sweeping power to detain people for failing to have a residence permit or valid ID. The issue had come to national attention after a twenty-seven-year-old university graduate was beaten for failing to have proper identity papers.

Teng, who is 41, is also a founder of gongmeng, the Open Constitution Initiative, a group of lawyers and academics who argue for greater rule of law and constitutional protections, and the New Citizens Movement, a broader group of civil rights activists. He is a lecturer at the University of Politics and Law in Beijing but has been banned from teaching since 2009 because of his political activities He is currently a fellow at Harvard Law School. I met him in Berlin in late August, a few days before he left for the United States.

Ian Johnson: This week, the Chinese Communist Party is staging its annual plenum—that much-watched event in which hundreds of members of the party’s central committee gather to discuss policy. This year’s theme is supposed to be “governing the country according to law.” Do you expect any significant changes to come of it?

Teng Biao: I don’t care what they talk about; I don’t expect anything. For the past two years they’ve arrested more than three-hundred human rights defenders and intellectuals, such as Pu Zhiqiang, Tang Jingling, and Ilham Tohti. And they have destroyed many Christian churches, they cracked down on the Internet, and they published a series of articles against universal values [an expression for human rights, civil liberties and other values that are enshrined in international law but often criticized in China as Western], constitutionalism, and judicial independence. With such actions, they can’t have meaningful reform of the legal system.

You’ve said that Xi Jinping is trying to bring China back to a totalitarian kind of system with a cult of personality. But in a totalitarian system, the government controls much more of daily life than is the case in China today.

He is not able to achieve totalitarianism, but he wants to. The problem for him is the civil society in China is stronger than he thinks. We have the Internet, we have globalization, we have a market economy.

It seems like a darker time today. In the 2000s, you had all these movements like the New Citizens’ Movement. But one by one they’ve been closed down, its leaders arrested, or silenced. Was there more hope a decade ago when you were finishing your Ph.D.?

In general I’d say that Chinese leaders have never stopped their crackdowns and control of civil society. They’ve arrested dissidents and leaders when they feel it’s necessary. So they arrested student leaders after 1989. They arrested the leaders of the China Democracy Party in the late 1990s, like Xu Wenli. They arrested Liu Xiaobo three times and many other democracy activists.

Late last year, the government said it had abolished laojiao [Re-education Through Labor, a practice according to which police had wide-ranging powers to detain people and send them to labor camps without trial]. Have they definitively repudiated this kind of detention or is it just cosmetic?

It can be considered progress, but in China there are many other methods of extrajudicial detention, such as shourong jiaoyu [detention for education] and shourong jiaoyang [work-study detention for juveniles], as well as black jails to detain petitioners, and shuanggui [extrajudicial detention for officials under investigation of wrongdoing].

So why did they abolish Re-Education Through Labor if they have so many other methods to detain people without trial?

Because this one is the most infamous. They faced pressure from civil society, such as in the Tang Hui case [in which a woman was sent to a labor camp in 2012 for trying to find the men who had raped her daughter] and also from the international community. Many people abroad know of laojiao but they don’t know the other methods.

Still, I think it is progress. It was so easy for police to put people in Re-education Through Labor. Since it was abolished they more often use the provisions for criminal detention under the criminal procedures law. According to that, the police can detain a person for thirty days without any involvement of the prosecutor or the court. But after thirty days they are supposed to apply for a formal arrest. If the arrest is authorized then the case enters the criminal procedure. If not, then they are released. So it’s more complicated to use these other methods.

Advertisement

Many foreign lawyers want to help their colleagues in China. What can foreign legal associations do to help?

The American Bar Association and others have some programs but the problem is the foreign lawyers’ associations misunderstand China’s bar association, the All-China Lawyers Association. It is called a lawyers’ association but it’s totally controlled by the Chinese government. Many foreign groups have programs and funding efforts but it’s not good to support the official lawyers’ association. They should support the weiquan lawyers. We human rights lawyers have some informal groups and some programs, like against the death penalty or torture.

What can foreign lawyers do with the human rights lawyers specifically?

Training or exchange. Sometimes they have meetings or conferences and don’t invite us. If they only invite the official lawyers, they cannot tell you the truth.

If you’re working as a criminal defense lawyer in such a system, how can you help your client?

Every level of government has a zhengfawei [Political and Legal Affairs Committee], which is run by the Communist Party. So judges are not independent. They must follow the orders from the government, especially in sensitive cases.

Most of the time we lawyers provide evidence, but even if it’s obvious that the defendant should be found innocent, the judge often cannot allow this decision. When they write the verdict they ignore what we’ve provided. So for us rights defense lawyers, our frequent strategy is to use the media, especially the Internet, to put pressure on the government.

Why would anyone want to become a criminal lawyer under these circumstances?

I got started because of the Sun Zhigang case, when we were shocked about how this man could be beaten to death just for having the wrong papers. The weiquan movement has also been helped greatly by the Internet because you can find other like-minded people. You see, in the past, the government pushed ideas like class struggle. But then, in the 1990s, it started to argue for “rule of law.” People began to realize that we can use this vocabulary to fight for civil rights.

And our numbers are growing. In 2003 or 2004, there were just twenty or thirty weiquan lawyers. But now It’s hard to define who’s a human rights lawyer. We find that when we take a sensitive case, more lawyers are interested in helping. Some are very active, like Gao Zhisheng or Pu Zhiqiang or Xu Zhiyong. For the active ones, I’d say there are two hundred. There are hundreds of others willing to take a human rights case. So all in all, maybe six or seven hundred.

Are these lawyers active throughout China or only in Beijing?

In 2004, 80 percent or 90 percent were in Beijing. In China there are 240,000 lawyers and one third are in Beijing. But especially since 2009, there have are now many in other cities, such as Guangzhou, Chengdu, Hangzhou, or Changsha.

People say that many weiquan lawyers are Christian. I know you are not, but is there an explanation for this?

Yes, about a quarter are. It’s not a coincidence. To be a human rights lawyer in China is very dangerous. More than 90 percent of the cases fail. We can’t see hope. So without God or a belief, a human rights lawyer would feel hopeless. For many, though, a belief in justice gives us strength.

So you remain optimistic, despite all the troubles?

I’m optimistic because although so many people are in prison new faces come forward all the time. The struggle for rights hasn’t won but it inspires people. Many citizens become prominent activists during these crackdowns. When Gao Zhisheng was arrested in 2006, Xu Zhiyong was not so active but then he stepped forward. Then Xu was arrested and others stepped forward. Now, after all the recent arrests, there are some names you won’t be familiar with now but they’re becoming active. It never stops.