“The conventional opinion about Egon Schiele’s 1915 portrait of his wife Edith,” writes Ian Buruma in the Review’s April 2 issue, “is that it betrays his romantic disappointment. His wife may have represented domestic calm, a point of stability in respectable Viennese society, and so forth, but she wasn’t sexy like his mistress Wally. So how does the apparently wholesome innocence of Edith’s portrait fit into Schiele’s oeuvre? Is it just an expression of conjugal assurance and erotic disappointment? Or is there more to it? I think there is. Looked at more closely, the picture still reveals Schiele’s fascination with the very Viennese entanglement of sex and death.” We present below a series of Schiele’s paintings of Edith, Wally, and himself, with commentary drawn from Buruma’s piece.

There she is, a gawky red-haired figure squeezed into a milky background, her slim hands clutching a multicolored striped dress, made by herself out of curtain material, her white shoes turned slightly inward, her wide blue eyes peering with childlike innocence from a pale-skinned face. The impression is of a doll-like creature, stiff, timid, not entirely in control of her own limbs. Edith’s helplessness could well have been part of her erotic attraction for Schiele: the shy bourgeoise who could be shaped by the older, more experienced artist.

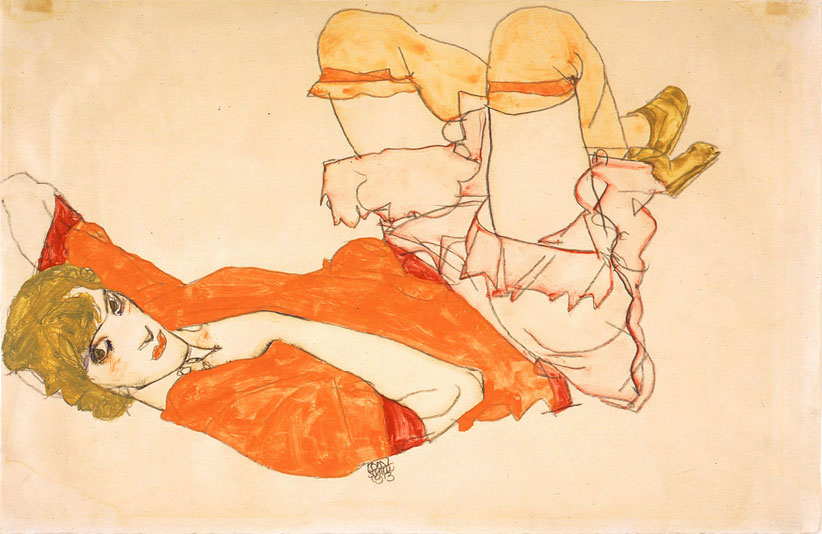

Schiele’s mistress and model, the free-spirited Wally Neuzil, looking at the viewer anything but innocently with her legs drawn up, as though waiting to be penetrated. Despite all his bohemian airs, Schiele did not regard her as a suitable wife. Himself the son of a humble stationmaster (who had been driven mad by syphilis at an early age), Schiele wanted to combine his artistic explorations of dark sexuality with the bourgeois comforts of settled domesticity. For this he needed a bourgeois wife.

Edith insisted that Wally should disappear from their lives, which she did with surprisingly good grace. How painful this was to both of them is revealed here: the man, resembling the artist, is holding on to the half-dressed woman, whose hands are clasped behind his back as though for the last time. The sepulchral brownish colors and shroudlike bed sheets set the tone. Both people look absolutely miserable.

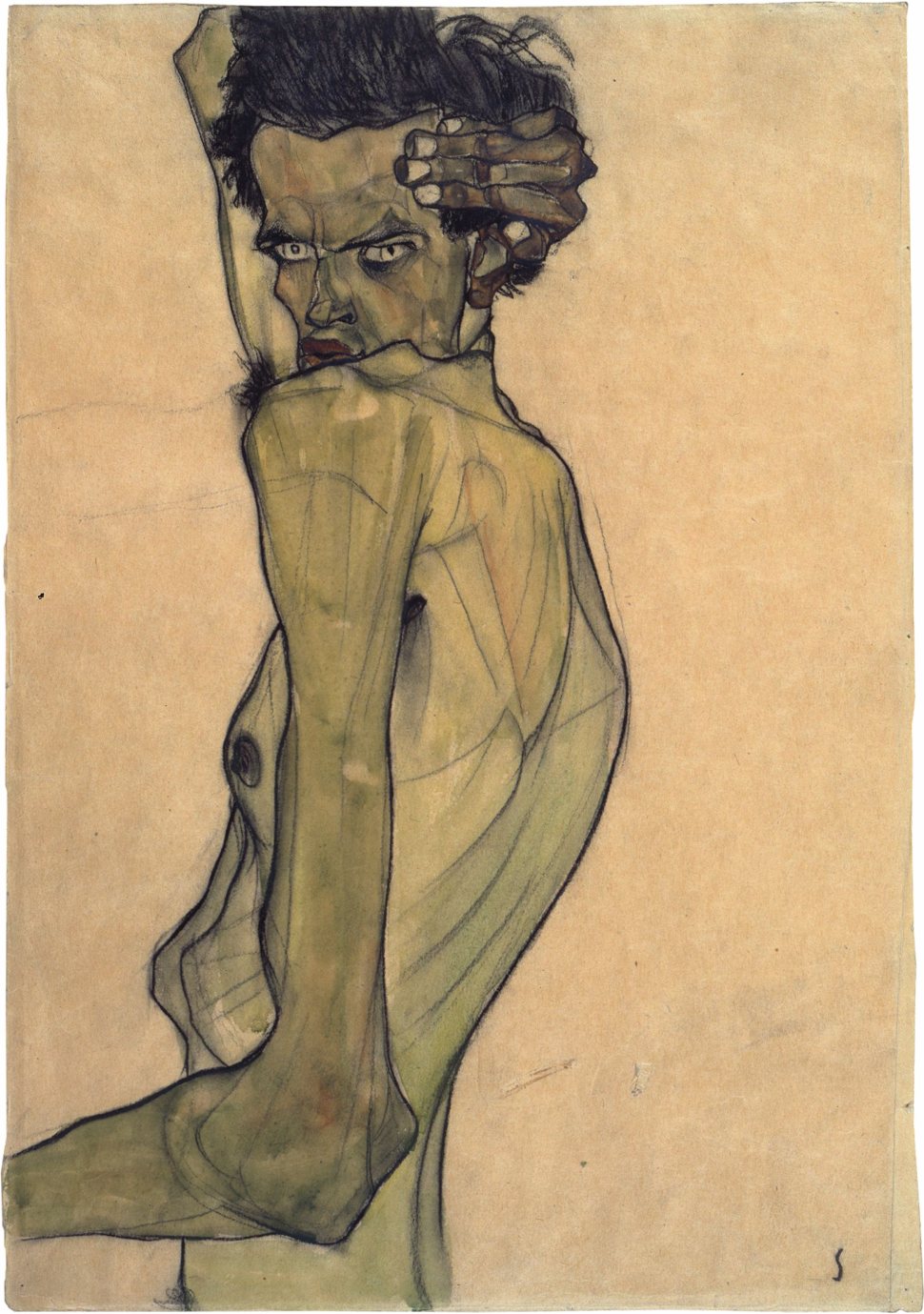

Many of Schiele’s human figures, not just Edith, have a puppetlike quality, including nude drawings of himself. In Self-Portrait with Arm Twisted Above Head (1910), shown at the Neue Galerie, Schiele is contorted like a marionette. The puppet can represent many things. One of these is the human body as something to be manipulated at will.

But then the doll-like quality about figures in Schiele’s paintings does not mean the absence of life. In 1915, the year he married Edith, Schiele began painting Mother and Two Children III. The mother, as in his earlier treatments of this theme, looks dead or close to death, her eyes hollow and unseeing in a sickly gray face. The two children, both modeled after Schiele’s own nephew, Toni, have the rosy cheeks and healthy tints of rude health. They are dressed, like Edith, in bright multicolored clothes. And yet, again like Edith, they have the stiffness of marionettes, waiting to be animated by a master.

“Egon Schiele: Portraits” is on view at the Neue Galerie through April 20.