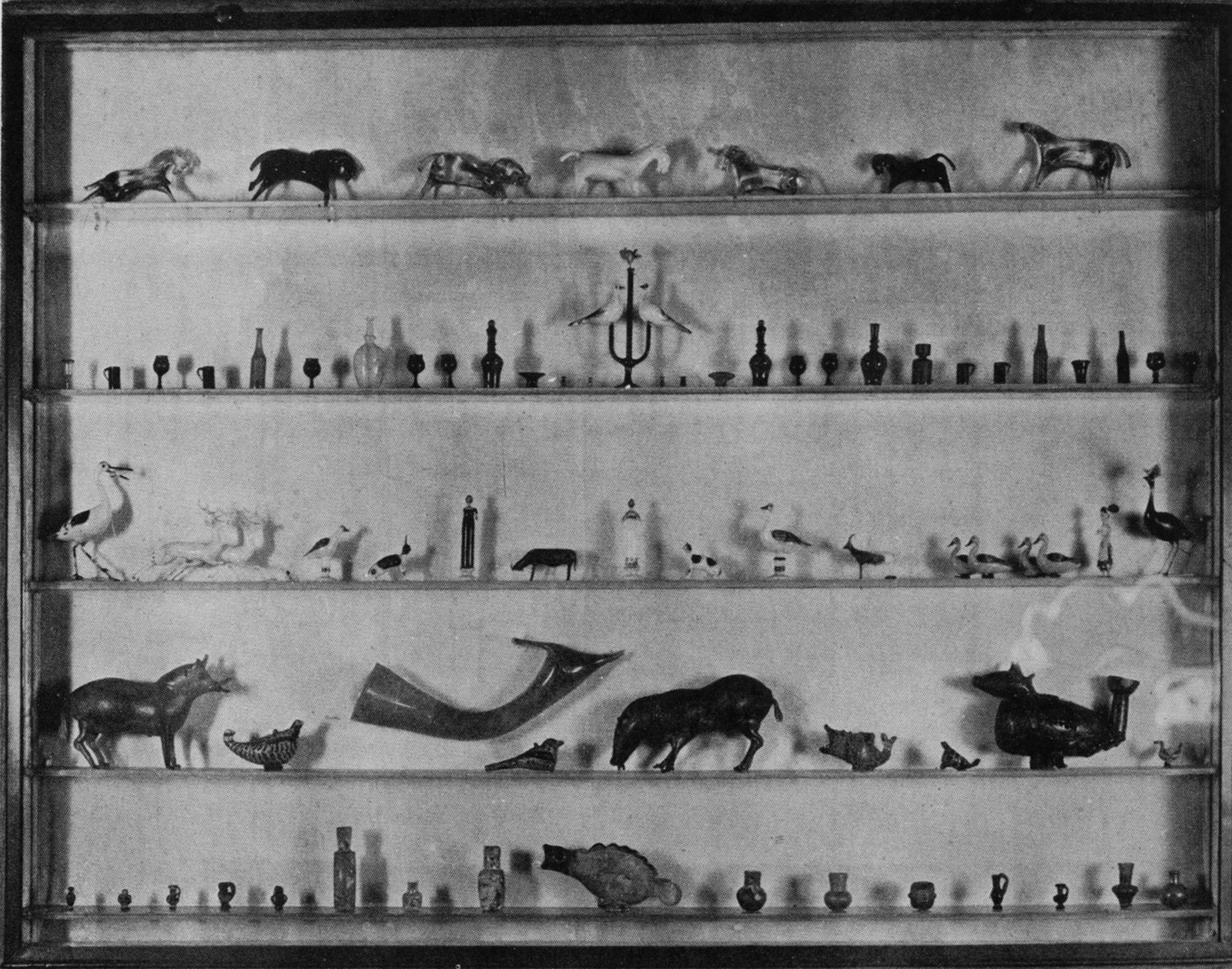

A multivalent exhibition now at the New-York Historical Society, drawn from the sprawling folk art collection of the sculptor Elie Nadelman (1882-1946) and his independently wealthy wife, Viola (1878-1962), is far more interesting than even its organizers seem to realize. The more than two hundred objects on display range from clipper ship figureheads (“It was not just a sailor who carved this but an artist,” Nadelman remarked of a ravishing gilded eagle with detachable wings) to miniature carved animals, amid a trove of carefully selected pottery, exquisitely detailed needle-cases, and an early, ingenious earthenware roach motel—the glazed, funnel-shaped opening of which traps roaches lured inside by molasses. This staggering array of material is complemented by a dozen or so of Nadelman’s wondrous figurative sculptures, fashioned in weathered cherry or mahogany and often given an overlay of seemingly aging paint.

The big news of the exhibition is that Nadelman (along with Viola, already a well-informed specialist, before their 1919 marriage, in antique lace and embroidery) was also among the first generation of serious collectors of American folk art and among the first to use the Germanic derived notion of a national “Volk” to confer prestige on such objects rather than the pejorative adjective “primitive,” favored by early twentieth-century enthusiasts of African masks, “peasant” carvings, and Native American pottery.

Encased in glass like additional works of folk art, Nadelman’s own works on view include the superb twin-figured Tango (which displays, according to New York City Ballet founder and Nadelman advocate Lincoln Kirstein, “an understanding of theatrical dancing such as no one had had since Seurat and Lautrec”) and his beguiling Piano Player: an upright musician at an even more upright piano, festooned with one of Nadelman’s signature bows in her hair and another behind her waist. Stop-framed in mid-motion with painted-on faces, his performers exude a Marcel Marceau air of deadpan isolation with an antic shade of Buster Keaton.

Born into a prosperous Jewish family in Czarist Warsaw in 1882, Nadelman, whose father was a jeweler of liberal opinions and “extensive philosophical background” (Kirstein again), studied briefly in Munich and was active in the most advanced artistic circles in pre-World War I Paris—where some (including himself) credited his early, classicizing sculptures, based on abstracted curves, with the conceptual origins of Cubism. When Nadelman exhibited his top-hatted Boulevardier and a Mercury-like figure sporting a bowler hat in 1914, his fellow Pole the poet-critic Apollinaire greeted them as “the first works in which a piece of modern clothing had been treated in an artistic manner.”

And what treasures they are! I think I could have looked all day at the astonishing “Bear and Pears” fireboard (circa 1825-1835), which served to block off a New England fireplace during the summer months, providing as much visual delight as the roaring flames in mid-winter. Painted in oils with a rag, a sponge, and an array of stencils, the picture has the deadpan wit and sheer, alienating strangeness—as though Grandma Moses had been tutored by Henri Rousseau—that one associates with some of the best of Nadelman’s own sculptures. The same is true of the spouted salt-glazed pitcher, made in Manhattan in 1798 by the master-potter Clarkson Crolius, Sr., “a constant delight,” according to Nadelman. The gray-glazed body of the pot is incised with a rich cobalt-blue pattern of leaves and blossoms, culminating in the upward thrust of the spout. Two looping handles resemble listening ears, giving the pot the look of an alert elephant, not unlike the dashing elephant pull-toy (1830-1880) in a case nearby.

Advertisement

Unlike nativist collectors such as the artist Charles Sheeler and Henry Francis du Pont, who during the 1920s amassed Americana in an effort to bolster nationalist claims to a distinctive artistic tradition, the cosmopolitan Nadelmans acquired both European and American objects. Viola, a native New Yorker who attended German schools in her peripatetic youth and was often referred to as Madame Nadelman, appears to have had a particular interest in medieval artifacts; the Nadelmans are said to have been the underbidders for the Unicorn Tapestries now at the Cloisters. If anything, their ethos was Eurocentric since they believed that their collection demonstrated the “derivation” of American folk art from European prototypes. While such a view allowed them to see how a potter like Crolius adapted traditions from his native Germany, it blinded them to influences from beyond Europe.

For example, the Nadelmans characterized their two vivid face jugs (circa 1860-1880), from the pottery-rich Edgefield District of South Carolina, as “monkey jugs,” and displayed them with earthenware squirrels and monkeys, along with a toy fiddler with African-American features. But these jugs, with their wide-open eyes and gritted teeth highlighted with white kaolin clay, are not caricatures of black people, as the Nadelmans apparently believed, but rather African-derived sacred vessels for the Kongo ritual of “conjure,” in which kaolin was considered a magical substance for contacting spirits. The juicy, brown alkaline glaze, moreover, was discovered by Edgefield potters trying to reproduce the celadon glazes of China.

If the Nadelmans were constrained by a rigidly linear theory of derivation, the exhibition at the New-York Historical Society, oddly, is encumbered by one of its own. Like a statue too big for its base, the exhibition is precariously balanced on a premise it cannot sustain: that Nadelman’s own sculptures were influenced in some significant way by the folk art that he and his wife collected after 1920. The arrangement of the show, with the folk art objects around the walls and the Nadelman sculptures centrally encased, suggests that folk art is the proper explanatory “context” for Nadelman’s work.

But any secure claim of direct influence must wrestle with an uncomfortably tight set of dates. The doll-headed Piano Player, for which Nadelman made a plaster maquette as early as 1919, before he began his great collection, does indeed radiate a folk-art vibe. One of its twin bows, behind the amateur pianist’s waist, resembles the wind-up apparatus for a children’s toy of the kind that, as the catalog awkwardly states, the Nadelmans “would soon collect.” A marvelous chalkware bust of a woman, of a kind originally hawked by traveling peddlers, has an ornamental bodice that resembles Nadelman’s bust of 1924-1925. “Is it a coincidence,” a catalog contributor asks, “that Nadelman ornamented his bust’s dress with a scalloped blue collar that reverses the red scalloped bodice trim in the chalkware piece?” One feels a bit bullied by the rhetorical question, to which one is tempted to answer, “Well, maybe.”

A catalog essay, placed last, by Barbara Haskell (who organized the 2003 Nadelman retrospective at the Whitney) rejects any influence from American folk art, arguing instead that Nadelman’s primary aesthetic project was a fusion of classicizing models from Greece with Baudelaire’s injunction to embrace contemporary life. Both arguments, for and against the possible absorption of folk art practice into Nadelman’s own work, seem unnecessarily narrow to me, aiming for a precision in tracing influence that is simply impossible by the early twentieth century, when the taste for all kinds of art, high and low, was widespread, and the various ways they were interconnected are not always clear. The catalog writers are on more secure ground when they concede that “his sources may have been multiple.”

More interesting, I think, is the influence that went the other way: as Nadelman’s distinctive temperament, encouraged and perhaps expanded by Viola’s own enthusiasms, guided his collecting. Indeed, the exhibition might be better viewed as a display of found art rather than folk art, as Nadelman—whose 1920s collecting was his major creative work of the decade—discovered analogs in mostly anonymous art that confirmed his own aesthetic tendencies. The gilded eagle figurehead that turns its head just so, the pull-toy elephant on wheels, the mesmerizing bears and pears: it took a Nadelman to see these, and to place them in the charmed circle of his own collection. These works look like Nadelman’s because they are Nadelman’s. And this is why it was so wrenching for him, tragically so, to have to part with them.

Advertisement

With extensive real estate holdings, including a double townhouse at Fifth Avenue and East 93th Street, the Nadelmans lost everything in the 1929 crash and eventually sold their collection to the New-York Historical Society, where Nadelman briefly and unhappily served as a curator. During the ensuing years, Nadelman became increasingly reclusive, secretively developing a new line of sculptures, in molded clay, that seem a radical departure from his previous work—like mass-produced figurines come upon in a tag-sale. A son fought in World War II, in France and Germany, and he himself volunteered to work with veterans in a hospital in the Bronx, providing art materials for men suffering from PTSD. Elie Nadelman died by his own hand, in his Riverdale bathtub, in 1946. Viola, expert in needlework, knit socks for Allied soldiers overseas during the war, and continued, until her death in 1962, to be a stalwart advocate of her husband’s art and for the extraordinary collection they had amassed together.

“The Folk Art Collection of Elie and Viola Nadelman” is on view at the New-York Historical Society through August 21.

![Yolande Délasser: Water jug [Spouted pitcher], circa 1936; painting of the spouted pitcher by Clarkson Crolius, Sr., 1798](http://www.nybooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/spouted-jug-drawing.jpg)