The following stories by Robert Walser, newly translated by Tom Whalen, are drawn from Girlfriends, Ghosts, and Other Stories.

—The Editors

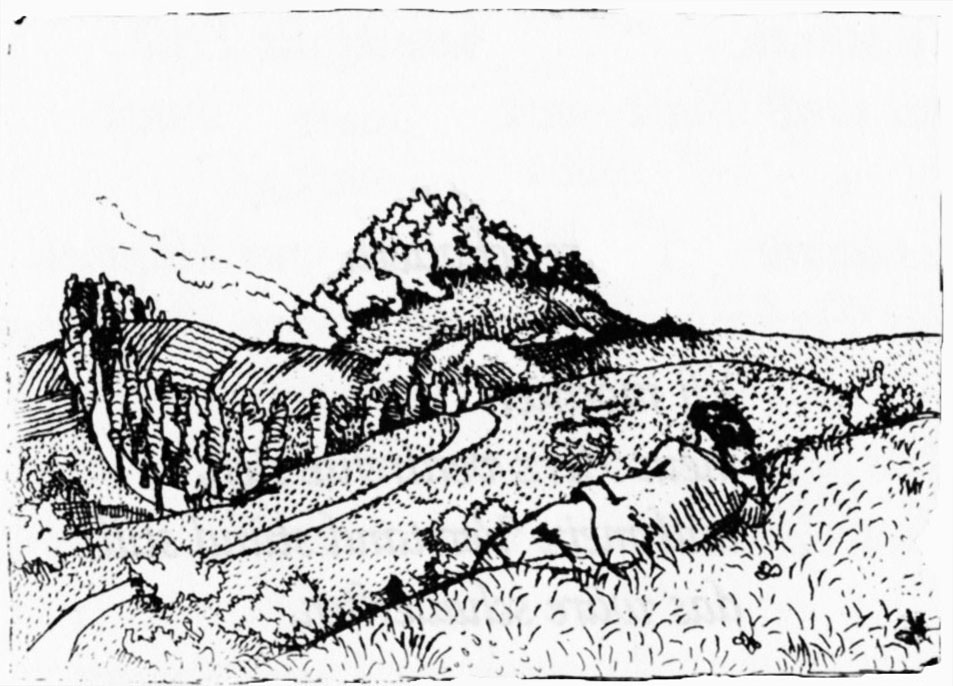

LUNCH BREAK

One day during my lunch break I lay in the grass under an apple tree. It was hot and before my eyes everything swam in the light green air. The wind swept through the tree and through the beloved grass. Behind me lay the dark edge of a forest with its somber, faithful firs. Desires swarmed through my head. I wished for a lover to match the sweet-fragranced wind. Then, as I lay there comfortably and languidly on my back, with my eyes closed and face directed toward the sky, summer humming all around, there appeared from out of the sunny ocean- and sky-bright bliss two eyes that looked on me with infinite kindness. I also clearly saw cheeks drawing nearer to my own as if they wanted to touch them, and a wonderfully beautiful, as if formed from pure sun, finely curved, voluptuous mouth came out of the reddish-blue air close to mine as if it wanted to touch my mouth as well. The firmament I saw through my eyes I had pressed closed was completely pink and hemmed by a splendid velvety black. I looked into a world of pure bliss. But then all of a sudden I stupidly opened my eyes, and the mouth and cheeks and eyes were gone and all at once I was robbed of the sky’s sweet kiss. What’s more, by then it was time to go back down to the city, back to business and my daily work. As far as I remember, I was reluctant to get up and leave the meadow, the tree, the wind, and the beautiful dream. Yet everything in the world that enchants the mind and delights the soul has its limits, as does, fortunately, all that inspires fear and anxiety. With that I bounced back down to my dry office and kept nicely busy until closing time.

(1914)

REMEMBER THIS

Remember how you rejoiced at the sweet, fresh green spring, how enchanted you were by the silver-white, sky-blue lake, how you greeted the mountains, how you found everything beautiful that encountered you and you encountered, how you were enfolded by a splendidly vast, undisturbed freedom, and how happy you were in its embrace, how joyfully you took things as they came, how you enjoyed each beautiful, bright, dear day, how on the warm nights the moon gazed upon you like a brother in whom you placed all your trust and faith, how the many hours glided imperceptibly by like a pleasure boat rocking on the water, as if the water had fallen in love with carrying and by so doing felt an unspeakable delight in bearing weight and in stillness; how constant and still the old mountain was and how white clouds like glowing flames from behind the mountains climbed into the sky, how kindly the people greeted you on the now day-lit, now night-darkened streets as if you were their friend, though to them you had to be totally unknown, how the villages with their cozy homes and abundant gardens, resplendent with sweet, luxuriant disorder lay there as if dreaming of primordial times, how the grass and grains ripened so benevolently and delectably; how the hill curved and how the lowlands gently went on, how in the forest you were welcomed by an unnameable cloister-like calm and silence, as if you were meant to think you were strolling through the realm of vastness and oblivion, and how the dear, delicate birds sang in the forest, so that when you heard their song you immediately had to stand still and listen, deeply moved, as if you were hearing the voice of eternity; how you were moved by a child in its mother’s arms, how you saw an old man on his deathbed, and how it was your father who lay there dead, who had passed on to the silent land—remember this, remember this. Forget, forget nothing, don’t forget the sweetness, don’t forget the severity. If indifference and unkindness take hold of your being, stir your memory and think of all the beautiful, all the burdensome things. Remember there is life and there is death, remember there are moments of bliss and there are graves. Do not be forgetful, but instead remember this.

(1914)

ASH, NEEDLE, PENCIL, AND MATCH

Once I wrote a treatise on ash, for which I received not a little applause. In it I brought to light a variety of curiosities, among them the observation that ash possesses no resistance worth mentioning. In fact it’s possible to say something meaningful about this uninteresting substance only by deeper penetration; for example, if you blow on ash, it doesn’t in the least refuse instantly to disintegrate. Ash is modesty, insignificance, and worthlessness personified, and best of all, it’s filled with the conviction that it’s good for nothing. Can one be more unstable, weaker, more wretched than ash? Not very easily. Is there anything more yielding and tolerant? Not likely. Ash has no character and is more removed from any kind of wood than depression is from exuberance. Where there is ash, there is really nothing at all. Put your foot in ash, and you hardly feel you’ve stepped on anything. Yes, yes, that’s the way it is, and I doubt I’m very much mistaken if I dare to say that we need only open our eyes and look around carefully to see valuable things, if we look at them closely enough and with a certain degree of attention.

Advertisement

Take the needle, for example, which as we know is just as pointy as useful, and which doesn’t tolerate being dealt with roughly, because as tiny as it is, it still seems to know its true value. Regarding the little pencil, what makes it so remarkable, as we have every reason to know, is that as it’s sharpened and sharpened, eventually there’s nothing to sharpen anymore, whereupon we throw it away, now that it’s useless through merciless use, and it occurs to no one, even from afar, to offer a word of acknowledgment or thanks for its many services. The pencil’s brother is called the blue pencil, and as has often been told, the two unfortunate pencils love each other like brothers, since they’ve struck up a delicate and intimate friendship for life. That’s three, then, as one in general can surely say, very strange, remarkable, and sympathetic objects, which, one just as much as the other, would possibly, that is, in the right situation, be suitable for a special lecture.

And what would the reader say to the little match or matchstick, just as dear as delicate, a sweet, odd little person, lying in its match-box next to its numerous comrades, patient, proper, well-behaved, as if adream or asleep. As long as the little match rests in its box, unused and unchallenged, it’s of no great value. It awaits, so to speak, that which is to come. One day, though, one takes it out, presses it against the rough surface, scrapes its poor, good, dear little head until it catches fire, and now the little match flames and burns. This is the great event in the life of the little match, by which it fulfills its purpose in life, does its good deed, and then dies a death by incineration. Isn’t that heartbreaking? The little match must miserably burn up, pitifully go to ground, while it performs its sweet task, awakening from its apathy, inactivity, and uselessness, revealing its worth, and smoldering with its eagerness to serve and do its duty. The moment the little match takes pleasure in its destiny, it dies; the moment it unfolds its meaning, it perishes. Its joy in life is its death, and its waking its end. The moment it loves and serves, it collapses altogether and expires.

(1915)

Girlfriends, Ghosts, and Other Stories by Robert Walser, translated by Tom Whalen with Nicole Köngeter and Annette Wiesner, will be published by New York Review Books on September 13.