In 2003, the Atlanta-based record label Dust to Digital released a six-CD anthology of prewar American gospel music called Goodbye, Babylon. The territory of that music was dauntingly varied and wide. Hellfire sermons, choral “sacred harp” songs, energetic group sing-alongs, solo performances of great fragility, swaggering performances by singers who flitted between spirituals and the blues: these were for the most part commercial recordings, often arranged by talent scouts like Columbia’s Frank B. Walker and released in pairs on 78 rpm records designated for specific markets (in the case of the set’s many recordings by black musicians from the South, “race records”). Some were exultant songs of praise. But many others were dark and doubt-haunted. They spoke of devils and temptations, of communities in decline, of pleas for divine salvation that might not be answered or heard.

Of the range of musicians included on Goodbye, Babylon—Baptist and Pentecostal, urban and rural, black and white—the Texas singer and preacher Washington Phillips was both one of the best-known among gospel enthusiasts and one of the most mysterious. The sixteen songs he recorded for Walker in five Dallas sessions over three consecutive Decembers—1927, 1928, and 1929—had been available together since 1979, and some began circulating on compilations well before then. (Another pair of songs, now lost, was recorded but never released.) In his own time, Phillips had been a brief commercial success. His first 78 sold more than eight thousand copies, and one wonders how many other songs he’d have had the chance to record if the Depression hadn’t forestalled his three-year-long career.

That career, like those of many of the singers on Goodbye, Babylon, grew out of a much longer record of local preaching and singing. For twenty years before his Dallas sessions, Phillips had been playing—in churches, at local functions, and at his house in a small farming community outside Teague—for neighbors and fellow believers; he kept doing so long after his last 78 appeared. (As a young man he experimented with Pentecostalism, but he spent much of his later life installed as the reverend of a local Baptist church.) In his case, performing in this atmosphere was a chance to develop a technically confounding and startlingly original kind of gospel song. Phillips’s Columbia recordings are sermons or hymns, some of them covers and others original, bleated out in a clear, confident but warbling voice and backed only by the harp-like plucking of a mysterious stringed instrument his studio documents called, cryptically, “novelty accomp.”

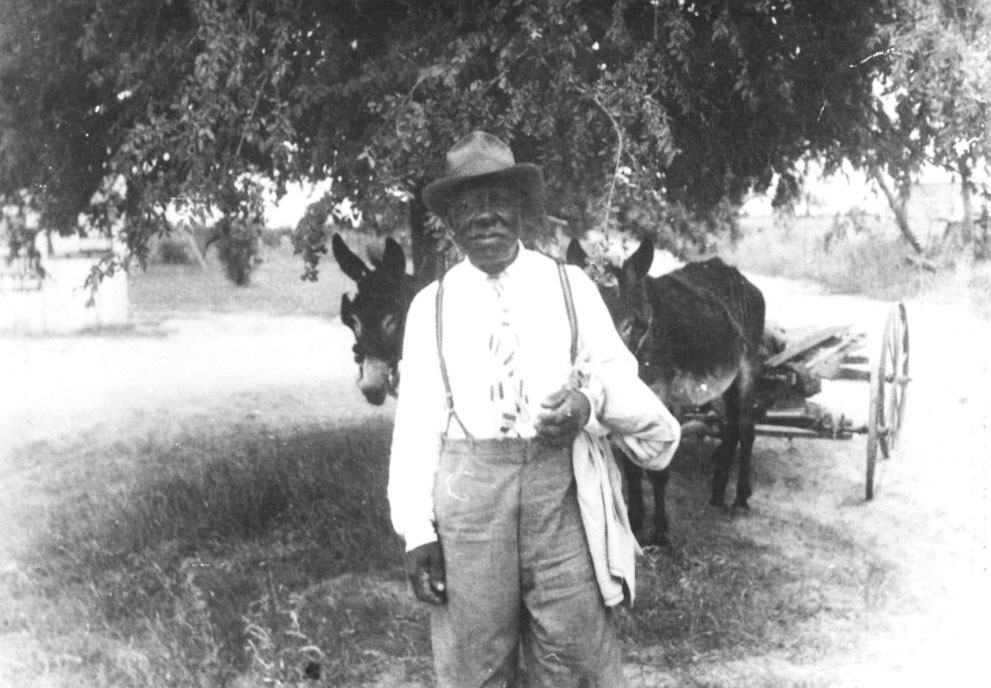

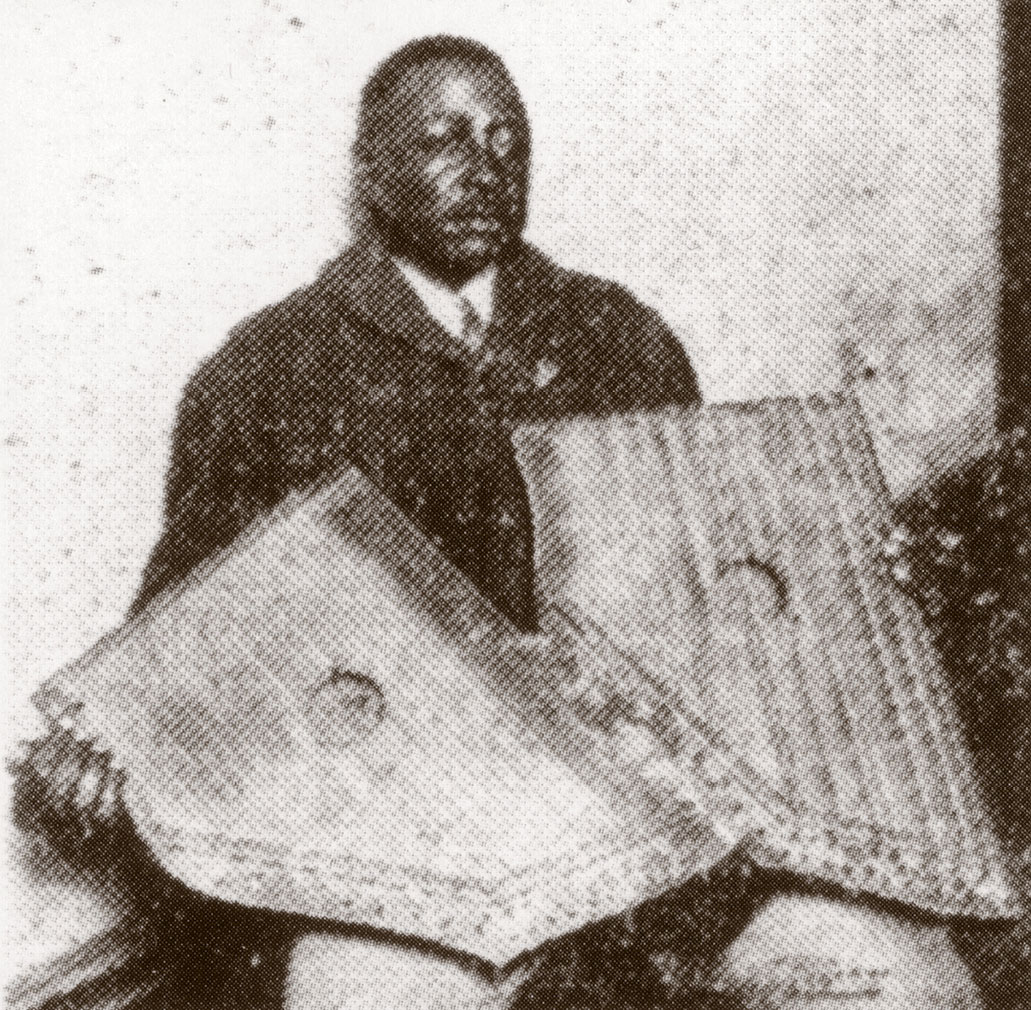

For decades, reliable information about these songs was scarce. Phillips’s biography, as the music critic Michael Corcoran discovered in 2002, had been partly confused with that of his cousin, who died in a mental institution sixteen years before Phillips’s own death from a fall in 1954. The singer was born in 1880—his parents had spent their early childhood in slavery—and raised on the family farm in Simsboro. His instrument was commonly identified as a dolceola, a rare hybrid of a keyboard and a zither. Corcoran disproved that theory in the same article, and in the past years there has been much lively speculation about Phillips’s invention among collectors of rare or handmade instruments. Drawing on a photograph from one of Phillips’s sessions, some think he played two fretless Phonoharp zithers at the same time. One of the discoveries Corcoran reports in his essay for Washington Phillips and His Manzarene Dreams, Dust to Digital’s authoritative new edition of Phillips’s music, is a 1907 item from the Teague Chronicle suggesting that Phillips used a kind of “box…[on] which he has strung violin strings,” which corroborates some eyewitness accounts but raises more questions than it answers.

In his hands, Phillips’s mysterious instrument produced a delicate, twinkling, almost whimsical sound. But the emotional terrain of his songs was more complicated than his melodies suggested on their own. Phillips was a seasoned jackleg preacher, and many of his songs are either sermons (“Train Your Child”), scenes of lesson-giving (“A Mother’s Last Word to Her Daughter”), or reflections on the profession (“I Am Born to Preach the Gospel”; “The Church Needs Good Deacons”). These sermons required him to take up the persona of a confident educator, sure enough in the truth of his lessons that he’d want to record them for a wider and more diverse public of believers than his local performances would have reached. He was quick to moralize and rebuke—to warn parents, for instance, that “it’ll be too late to cry/when you see [your children] going to the pen.” When he did so, his voice was often marked by an unnerving assurance, a sense of cutting through trivialities to arrive at a hard and urgent truth.

Advertisement

But there is another tone that often emerges across Phillips’s songs—a sense of vulnerability that undercuts the confidence his sermons project. The figures in his songs, as in many prewar gospel recordings, tend to be persecuted and burdened, doomed to roam a world of “sin and woe.” Phillips’s 78s would have been distributed specifically among black listeners, and one wonders to what extent the woeful worlds he described would have suggested the pervasively segregated and threatening one in which those listeners lived. As Corcoran observes, Phillips’s two brothers left Simsboro around the time, in 1922, that the murder of a white woman and the subsequent lynching of at least three black men turned the nearby town of Kirvin into a “racial battleground.” Phillips stayed, and it’s as if some of his more vulnerable performances absorbed the mood of anxiety and peril those events left. (Well before then, Phillips’s skin color had been the occasion for a more personal indignity. “He is as black as the ace of spades,” the 1907 Teague Chronicle author remarked, “but the music he gets out of that roughly made box is certainly surprising.”)

Listening to Phillips, you sense that his confidence didn’t come easily, that he had to keep reminding himself of the consolations he preached. This interplay of assurance and unease generates a strange kind of energy in songs like “I Had a Good Father and Mother,” for which the refrain is a wordless sung melody of deep tenderness and melancholy, or “Paul and Silas in Jail,” which Phillips recorded in 1927. Forty-five seconds into the latter song, Phillips’s voice, usually crisp and precise in its enunciations, falters and slurs a line (“’cause you believe in Jesus”) indecipherably. Then, in relating how the jailed Paul and Silas resolved to “do our Master’s will,” it strengthens and regains its clarity. In the song’s story, it’s only once Silas starts singing that “Heaven [gets] all stirred up” and the pair’s jailer converts in fear and trembling. In some moods, for Phillips, singing was just another form of preaching. In others, for him as for many gospel singers, it was what one did—amidst doubts and frustrations—to give oneself heart for the job.

Washington Phillips and His Manzarene Dreams is available from Dust to Digital.