When Kate Millett died, half-forgotten, on September 6 at the age of eighty-two, obituary writers struggled to take the full measure of this pioneering feminist writer and activist. Maybe Second Wave feminism now seems so far away that we’re hazy about what once made it so thrilling and threatening. Let me state it plainly: Millett invented feminist literary criticism. Before her, it did not exist. Her urgent, elegant 1970 masterwork, Sexual Politics, with its wry takedowns of the casual misogyny and rape scenes that had made the reputations of the sexual revolutionaries du jour—Norman Mailer, Henry Miller, D.H. Lawrence—introduced a new and remarkably durable idea: you could interpret literature in light of its gender dynamics. You could go to novels and poems for an education in sex as power. You may not agree that literature is the proper medium for consciousness-raising, but you can’t deny that Millett made reading a life-changing, even world-changing, act.

Millett was preceded by a great many other “lady critics,” as they were then infuriatingly called, the most estimable being, of course, Virginia Woolf. But Woolf was a more traditional reader, if also a subtler and more brilliant one, and not quite so single-mindedly focused on sex. After Millett came Adrienne Rich, Elaine Showalter, academic feminism, gender theory, queer studies, and all the still-ramifying dismantlings of patriarchy that dominate the study of culture today.

Millett was a synthesizer. She popularized the ideas bubbling up in the radical feminist circles of New York and London. This didn’t endear her to the members of those circles, who didn’t like it when a sister turned into a media star. Germaine Greer and Shulamith Firestone did the same thing, but they didn’t make the cover of Time, as Millett did. But what set her apart was the breadth of her intellectual ambition. She wrote Sexual Politics as a dissertation in the English department at Columbia, but, graduate student or not, she was going to get to the bottom of how her sex came to be so degraded—if she had to take on all of human history to do it. “The second chapter, in my opinion the most important in the book and far and away the most difficult to write, attempts to formulate a systematic overview of patriarchy as a political institution,” she states in the preface. Grandiose? Sure. But also: what guts!

If some of Sexual Politics, such as her long disquisition on Freud, feels dated, that’s partly because Millett changed the way we think about figures like him. Hardly anyone reads Freud literally anymore. “Penis envy” now sounds like a phrase you’d splash onto some ironic retro poster, not a real diagnosis. The idea that a political order based on domination has its origin in the subordination of women—well, it no longer seems novel, and she bears some responsibility for that, too. What remains enthralling, though, are Millett’s close readings, her exposés of the naked emperors of the literary left. “After receiving his servant’s congratulations on his dazzling performance, Rojack proceeds calmly to the next floor and throws his wife’s body out of the window,” is Millett’s deadpan description of the aftermath of the hero’s sodomization of a maid in Mailer’s An American Dream. Millett then observes, “The reader is given to understand that by murdering one woman and buggering another, Rojack became a ‘man.’”

Millett has been accused of conflating author and character—Mailer and Rojack, and so on, a charge that isn’t always unfair but doesn’t necessarily absolve the authors of swinishness. She’s at her very best, though, when she writes about an author she loves, Jean Genet, whom she understands to be “doing gender” (a phrase she wouldn’t have used, of course). That is, in telling stories of sadistic pimps and submissive drag queens, Genet enacted a parodic critique of gender norms (more phraseology she wouldn’t have heard yet). Genet’s novels, she writes, “constitute a painstaking exegesis of the barbarian vassalage of the sexual orders, the power structure of ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ as revealed by a homosexual, criminal world that mimics with brutal frankness the bourgeois heterosexual society.” (Any academic capable of writing a phrase like “barbarian vassalage” should have been awarded a Distinguished Professorship.)

Millett could be sloppy in her scholarship, as Irving Howe sniffed in an epic-length obloquy in Harper’s. “Brilliant in an unserious way,” he wrote, unserious being the most damning thing you could say about an intellectual if you were a New York member of the species. She quoted tendentiously, which was Mailer’s complaint (one of them, anyway) in “Prisoner of Sex,” a bellow of wounded pride that was even longer than Howe’s and also published in Harper’s.

Advertisement

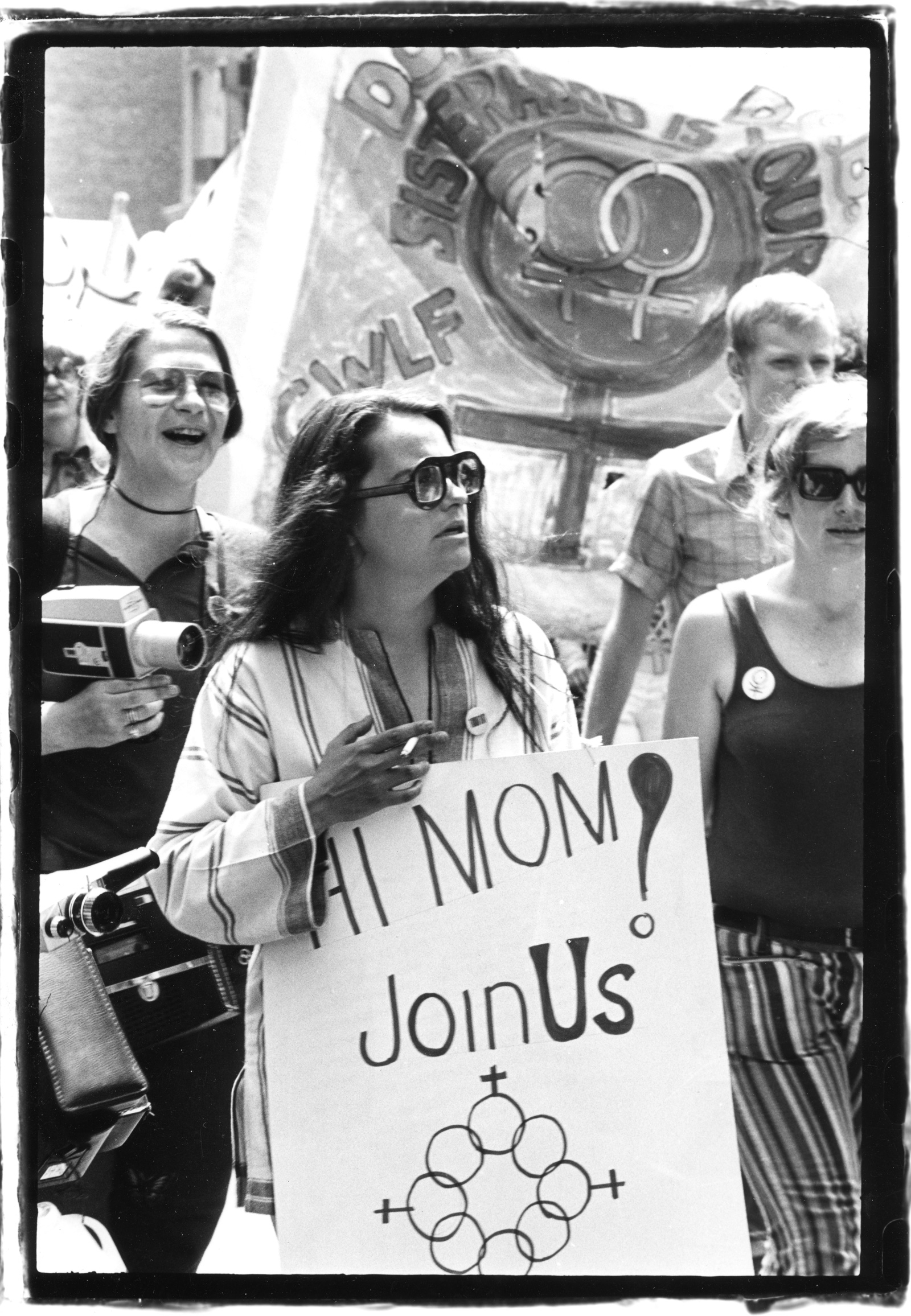

But these were quibbles, and couldn’t stop her hurtle toward fame. For a glorious moment, this very bookish literary critic was the face of American feminism. The New York Times called her the “high priestess.” After “Prisoner of Sex” became the talk of the town—and the revered Harper’s editor Willie Morris was fired for publishing it—Mailer organized a riotous debate known as “Town Bloody Hall,” which was filmed by Chris Hegedus and D.A. Pennebaker and is now streamable. It was a circus, and it was Millett who set it in motion, even though she refused to show up. Mailer aimed a torrent of insults at the feminists who did agree to take the stage or appear in the audience, among them Greer, Diana Trilling, Susan Sontag, Betty Friedan, and Cynthia Ozick. They rolled their eyes and gave as good as they got—much better, in most cases—and the crowd roared with delight. Try to imagine a public clash of ideas being so joyously gladiatorial today.

And then Millett faded away. She is owed a posthumous apology for the shameful way she was pushed out of the limelight. What did her in was the revelation, also in Time, that she was bisexual. Her non-heterosexuality irked Friedan, who feared more than just about anything that Women’s Lib might be tainted by the “lavender menace.” And Millett’s failure to commit to lesbianism outraged the militants on the other end of the spectrum. “The line goes, inflexible as a fascist edict, that bisexuality is a cop-out,” Millett later wrote. Confronted by a group called the “Radicalesbians” at a meeting that promptly made its way into Time, Millett said, “Yes I said yes I am a Lesbian.” She added, “It was the last strength I had.”

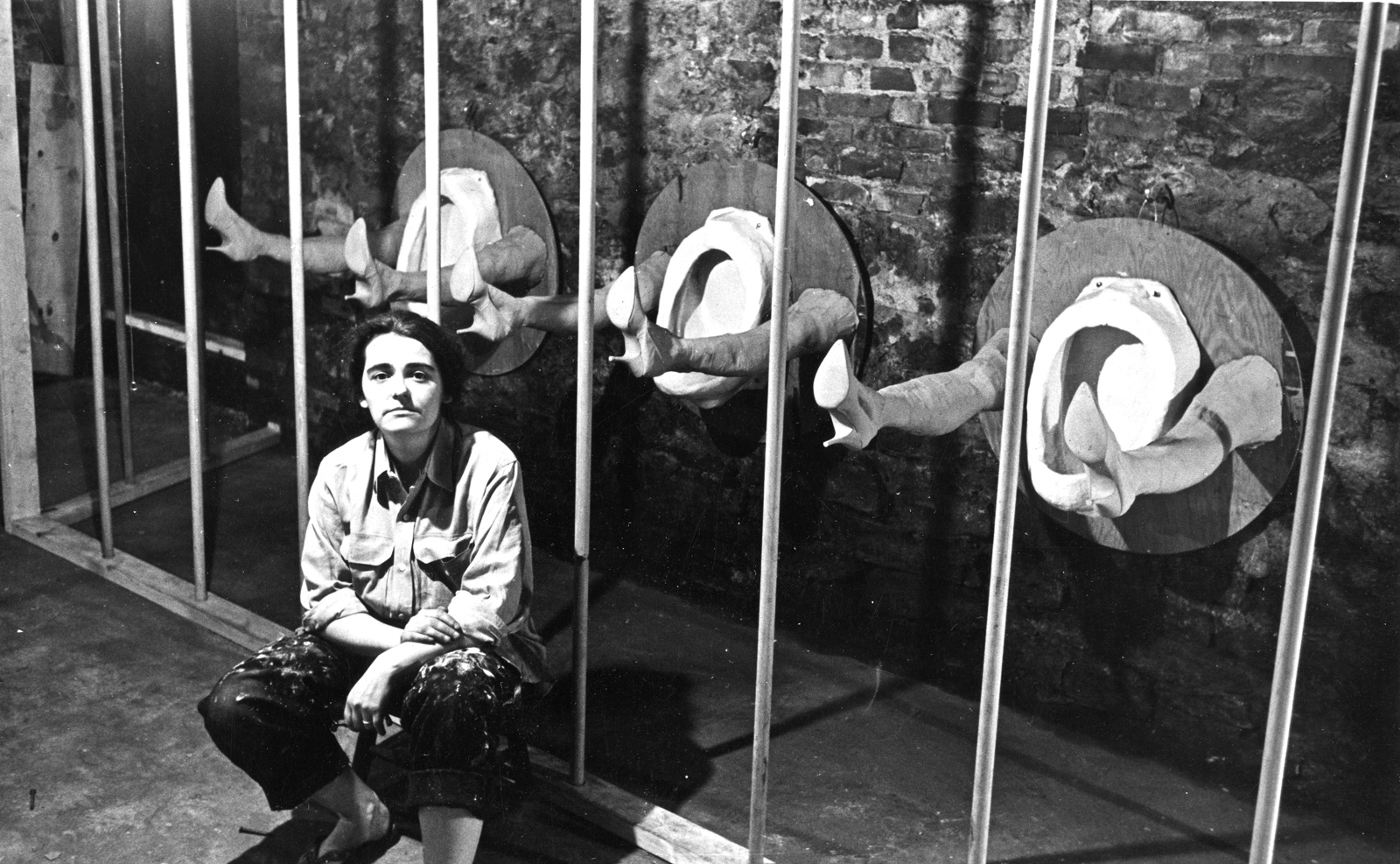

It was her last strength because Millett suffered from acute manic depression and couldn’t cope with the demands of being a celebrity public intellectual. Even as she continued her rounds of speeches and political activities, she began to withdraw to her farm upstate. Unstable, suicidal, she had to fight her own friends and family to get out of the mental hospitals they committed her to. She spilled garbled and unedited confessional memoirs into journals and then into print. Maybe she was acting on the feminist credo that the personal is political, and there are occasional flights of genius in these books. Flying (1974), which she wrote more or less while on book tour for Sexual Politics, is simply unreadable, but The Loony-Bin Trip (1990) deftly describes her slide into paranoia when she went off lithium, as well as a stint in an Irish mental hospital. The unreliable narrator toggles between sleeve-tugging ratiocinations and exquisite descriptions of the heightened consciousness that accompanies a state of mania. On the whole, though, her writings after Sexual Politics leave you wanting to flee her excruciating, stuttering vulnerability.

As a result of her flameout, we have done Millet the disservice of not treating her as the major figure she was, of not taking on Sexual Politics the way we take on, say, The Feminine Mystique. Today she is faulted for having been insufficiently intersectional. “Millett and her fellow radical feminists often elided crucial differences between women—black and white, working-class and wealthy—in the name of ‘sisterhood,’” wrote Maggie Doherty in The New Republic. Millett did think in big, unnuanced categories, though I somehow doubt that she would have had patience for the word “sisterhood.”

But to my mind, Millett made a more consequential mistake in Sexual Politics, though she wasn’t the only one to make it. Her error was the error of Second Wave feminism, and it nearly did the movement in. It is that she wrote off the family. This was the part of the feminist package that most alienated your average American woman—that, and the claim that their failure to extricate themselves from this feudal institution reflected “false consciousness.” In Millett’s neo-Marxist conception (Firestone’s, too), the family was in its essence coercive, hierarchical, a means of reproducing the patriarchy. Millett and Firestone weren’t very pro-child, either. Having babies and taking care of them reduced women, Millett wrote, “to the cultural level of animal life in providing the male with sexual outlet and exercising the animal functions of reproduction and care of the young.”

This was wrong-headed. Marriage and family life may have amounted to glorified (or unglorified) slavery for women throughout much of human history, but they weren’t slavery when Millett was writing, and they definitely aren’t now, at least not in the developed world. The family isn’t perfect, heterosexual spousal relations unquestionably privilege the husband, and wives are still being penalized economically and socially for the free labor they put into raising children and maintaining homes. But married women aren’t helots, and they weren’t fifty years ago. When women had no right to own property or refuse sex, when their children belonged to their husbands, when they had little means of support other than fathers or husbands unless they worked for slave wages, then they were slaves. But women have most of those rights now, and somewhat improved work conditions, and it’s safe to say that they are in no rush to abolish the family.

Advertisement

On the contrary. The firebrands Millett ran with in the Sixties could never have imagined that the family would come to occupy a central place in contemporary progressivism. Nowadays, we have to fight to save the family against the disruptions of capital and forces of reaction that threaten to pull out props like health insurance and public education. No young socialist feminist would have guessed that marriage would become, not a prison for the unenlightened, but a luxury item unaffordable for many low-income Americans. A gender-fluid person living through the unfettered Sixties and Seventies would surely have been stunned if you’d told her that the fight for gay marriage would become the most successful example of left-wing organizing half a century hence. In Millett’s day, feminists demanded subsidized day care—as they should have, and must continue to do—but that was because they were trying their damnedest to get out of the home and into the workforce. They weren’t quite as alive to issues like paid family leave, which is, after all, a way to facilitate those “animal functions of reproduction and care of the young” that Millett disdained.

Millett devoted most of a chapter of Sexual Politics to attacking as fascistic and counterrevolutionary societies that emphasized family over sexual freedom. Her main examples were the Nazis and the Soviet Union under Stalin. This was ahistorical and naive. Neither Hitler nor Stalin had any respect for the family. The Nazis encouraged unwed motherhood if it meant more Aryan babies, and invented no-fault divorce so that Germans could rid themselves of Jewish spouses. The Soviets broke up families by staggering work schedules, turning children against parents, and sending wives to the gulag for failing to inform on their husbands. It’s painful to admit, but the condescending Howe, in his review, got this exactly right. “In every totalitarian society, there is and must be a deep clash between state and family, simply because the state demands complete loyalty from each person and comes to regard the family as a major competitor for that loyalty,” he wrote. “For both political and nonpolitical people, the family becomes the last refuge for humane values. Thereby the defense of the ‘conservative’ institution of the family becomes under totalitarianism a profoundly subversive act.”

Another development that the young author of Sexual Politics and her peers did not anticipate was how neatly their anti-family bias would dovetail with feminism’s swerve toward careerism. Best sellers like Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In, New York Times article after New York Times article, and, of course, Hillary Clinton’s benighted campaign have all dwelt obsessively on pay equity, shattering the glass ceiling, and other workplace concerns. Women have to have equality in the workforce, obviously, because they’re there to stay. But the women and, increasingly, men who are most egregiously discriminated against today are those who are not in the workforce, or only partly in the workforce, because they do the unpaid labor of care. These are the people who—at the risk of going all cosmic—keep the species alive, civilization going, and life itself bearable. And they are treated like dirt for it.

The family that Millett and her peers wanted to throw out the window turns out to be a source of love, and pleasure, and grounding, and meaning, that many people just aren’t willing to dispense with. In a grim global economy, raising children can look a whole lot more fulfilling than the grinding, underpaid, and insecure employment on offer. I don’t mean to say that there weren’t feminists in Millett’s time who grasped that the family needed saving, not destroying. But these groups (the National Welfare Rights Organization, Wages for Housework) were shoved to the margins of the movement. Wages for Housework was trashed as reactionary, because more mainstream feminists misinterpreted the group as trying to push women back into the home. It was just too soon to demand honor and dignity—and compensation—for the “women’s work” that had been demeaned for so long and used as a reason to deny women access to other opportunities.

Even though Millett never had children, and had to flee a traditional and disapproving Catholic family to realize herself as a radical and a lesbian, she needed that family to survive her many travails, as well as the little family she put together with her partner and her closest friends. Her memoirs of her time on the farm make clear that she found so-called drudge work to be gratifying and redemptive. She put up buildings by hand, cared for horses, grew food. Had she been able to re-enter the fray of public debate, perhaps she would have helped to steer the feminist revolution toward the people it will have to wrap its arms and minds around if it is really going to help all women flourish (and all men, too): not just the hewers of wood, etc., but also the pushers of strollers, the swabbers of kitchen floors, the givers of loving kindness and care.