Without mayonnaise, there could be no New Year in the Soviet Union.

A better half of holiday dishes hinged upon it. The sauce—though no one would ever call it that; mayonnaise was a thing-in-itself—came in 200-gram glass jars, and its metal lid had to be pried open; nothing was screw-on in those days. No label either. Just its full name, “Mayonnaise Provençal,” embossed on the lid, along with the expiration date. But the slim jar could not be confused with anything. Behind the glass, the mayonnaise had a grayish tint that would turn green once it mixed with the ingredients of salad Olivier, a Soviet rhapsody of cubed boiled potatoes, bologna, eggs, pickles, and canned green peas.

You could never just buy mayonnaise. You could only get it, sometimes in a favor exchange, sometimes at a special distribution center for important people, like party members or employees of the commerce sphere, most of whom were party members also, so it was one and the same thing. Some trade union members could access mayonnaise, too, though I never figured out which ones; my mother’s union couldn’t.

Factory stores were another path to mayonnaise. They’d sell deficit foods there before the holidays, to keep the proletariat off the edge—it was their country, after all—but you had to work at the plant to be eligible to shop there. My mother worked at the Institute of Culture, and they didn’t have a food store on the premises, let alone one that would trade in mayonnaise. The intelligentsia was an underclass, a “thin layer” between the proletariat and the peasantry Lenin had called it, so the state didn’t fuss about mayonnaise for its least-valued constituency.

Nor would the private markets sell mayonnaise. They’d sell everything else—poultry birds proudly displaying curly yellow fat in their cavities, as if in reproach to the bony and blue chickens sold in state grocery stores. Mandarins and pomegranates from Georgia, arranged in meter-high orange triangles. Sour cream so thick a spoon could stand up in it. Homemade cheeses, honey, produce, pickles of every imaginable vegetable or fruit, including apples. Prices were astronomical, but the stuff was there. Mayonnaise, on the other hand, was the monopoly of the Soviet state, and the state could never produce enough of it. So, if you wanted to meet the New Year properly, with your salad Olivier, your herring-under-a-fur-coat, and your stuffed eggs, you had to work it.

My mother, for instance, had an acquaintance in our local grocery store. Unlike most Soviet grocery stores titled simply “Grocery,” our grocery had a name: “Northern.” The origin of that name in a small southern town was obscure. The store may have been north of some important strategic object, like the district party committee or the nearby Air Force College for pilots from the Warsaw Pact countries. Or that name could have been a southerner’s dream of north, where snow was a guaranteed appearance for much of the New Year holiday, providing a necessary white backdrop for your New Year trees, hard-fought for, like everything else. In the south, where we lived, a rare snowstorm was an occasion for puddles and slush.

The Northern store employed exclusively women, most of them already divorced or still not married and therefore looking for a husband—the result of another deficit, but of men, not mayonnaise: a gender imbalance left behind by the war, they said, even though the war had been over for forty years. The grocery store women wanted to look good for the deficit men, and because there were no good clothes in the store, just as there was no good food in the groceries, they went to private seamstresses with their two meters of fabric, their threads, their buttons, and their zippers, and ordered skirts and dresses. One of those women, a cashier in the Northern, ordered her holiday clothes from my mom, who had trained herself to be a seamstress when she wasn’t teaching piano at the Institute, because every single mother in the USSR had to survive somehow, and that was her way.

In exchange for the skirts, the cashier would “hold” some of the foods that the state planners had dispatched and that had never quite made it to the food hall, preordained tokens in the complicated system of favors, bartering, and bribes that supplemented our perpetually collapsing planned economy. Everything good went straight under the counter. Like the yellow, pre-packaged butter that didn’t leak water as its pallid cousin sold by weight did. Imported spaghetti that, unlike the output of our local macaroni factory, didn’t turn into a sticky clump during cooking no matter how much you stirred it. Ham without fat and bones. Canned green peas.

Advertisement

The green peas were almost as an sich as mayonnaise. If imported spaghetti could at times be acquired at the end of a two-hour-long line (strictly two packs per pair of hands, no more), and if one could conceivably live without ham, canned green peas were a critical ingredient of salad Olivier and, thus, of the New Year holiday. The holiday, ever since “bourgeois” Christmas had been cancelled. Yet never in my life had I seen a can of green peas on a shelf of our Northern grocery.

There was a place for it, though. A friend of a friend just returned from Cuba, I had once overheard my mother’s client saying during the fitting, which took place in my room since that’s where the mirror and the sewing machine were. That friend was a surgeon, dispatched to help revolutionary Cuba because it lacked qualified medical professionals. He’d come back shaken. The only grocery on the shelves of their grocery stores, the surgeon had told the friend of a friend: cans of Soviet green peas. It was reassuring, of course, to know that someone had it worse than you, and to have solved the mystery of green peas’ absence, but questions remained. Did the Cubans need green peas as much as we did? In their faraway tropical country, did they even have salad Olivier? And above all, did they know of our sacrifice?

When making Olivier, green peas were always the last to make it into the pot, a prelude to the mayonnaise. Each can of peas produced about half a glass of sweet juice that my mother would always hand to me, and that, as a single child, I didn’t have to share with anyone. Strained of their liquid, the peas tumbled out of a can in a merry green avalanche, the only round shape in the kingdom of cubes.

Then came the mayonnaise, the thing that held everything together. It had a distinct taste, with hints of sharp mustard and white vinegar, and sunflower oil, too. If an open can was left in the fridge for a couple of weeks—say, when you’d overdone it with the favor channels and received several jars—that oil would separate, forming a thin yellow refrigerator-hardened layer on top of the unused mayonnaise that, as time went by, would get crisscrossed with cracks, like mud at the bottom of a drying puddle. You could restore the original composition with a fork, and while it somewhat lacked in freshness, it was good enough to be slathered on a piece of dark bread, concocting the memory of the holiday.

But that would be next year. On December 31, as the New Year tree (an atheist state’s answer to the Christmas tree) spread the scent of pine resin over the apartment, its fragile snow-maidens and icicles scintillating in the light of a ceiling lamp, the mayonnaise was still sharp and plentiful. It poured easily out of a jar and had to be incorporated slowly with a spoon, starting from the top of the salad mound, and going down in concentric circles all the way to the bottom, until each small cube was smothered in the magic sauce. You could check by tasting the salad from various sides of the pot, though you had to go easy, or there would be not much left for the holiday table.

By the time the Olivier made its public appearance, around 9 PM, it had been freed from its prosaic container and heaped in a cupronickel-rimmed crystal bowl that, in the ordinary times, gathered dust on the living room windowsill, a memory of a wedding that didn’t live up to its expectations. Soaked in the solution of vinegar and salt, scrubbed and patted dry, the sparkling bowl was an appropriate framing for Olivier—the king of the table, and evidence of man’s triumph over adversity.

Also on the table, golden Riga sprats, reminders that the Baltics were Soviet, too. Canned crabmeat from Kamchatka, nine time zones away in the far north. A platter with thinly-sliced servilat, a species of hard salami so rare that even my mother’s friend in the Northern grocery, with all her under-the-counter power, could not procure any. When my grandfather was alive, it came from him, part of a special holiday food packet that he would send us from the nearby town where he lived.

The most amazing thing in that packet was a list with the “state” price for every food item it contained. A can of Chatka crabmeat: two rubles, eighty five kopecks. A can of salmon caviar: two, seventy. A can of cod liver: one, fifteen. A kilo of servilat: five, ten. The whole thing amounted to some fifteen rubles. Even with our meager incomes, we could have afforded it, had the items only been in the stores. But they weren’t. When we would go to my grandfather’s, Mother would pay him back the rubles and kopeks she owed for the holiday packet without saying a word, but I knew she couldn’t square it away, why a man who had everything insisted on the reckoning part. He had his reasons, we assumed. Something to do with children not depending on their parents.

When he died abruptly, my mother had to find new procurement channels. They came in the shape of my better-off classmates’ parents, her occasional boyfriends, and, sometimes, her students. Once, it was a balalaika major taking mandatory “general piano” classes who worked at night at the city’s meat processing plant and left the premises with sausage links tied to his back or legs, to be used as currency. Everyone did that, he confided to my mother, and not everyone got caught. That’s why an unskilled laborer’s job at the meat-processing plant was something of a boon.

And then the servilat that had made its way to our holiday table through such peril was arranged, sliced fan-style, on a dinner plate. Next to it, in a fish-shaped dish, herring-under-a-fur-coat spread its cruelty-free mantle of boiled carrots, beets, potatoes, and raw onions. In this second mandatory New Year dish, mayonnaise acted as a divider, separating one colorful layer from another. In another crystal bowl—emptied for the occasion of Mother’s rings and necklaces—was shredded carrot salad with walnuts and raisins, the carrots’ orange flamboyance tempered by the mayonnaise. Boiled eggs, halved and stuffed with the yolks that had been whipped with crushed garlic and mayonnaise, mandatory dish number three. Sandwiches spread with melted grated cheese, garlic, eggs, and, of course, mayonnaise. Smoked cod liver on toast, or chopped with eggs and green onion, both versions so filling you could only manage a few bites, and with great care not to drop any on the tablecloth or your dress, because the fish stink would be impossible to get out. Fresh herbs bought in the produce market and laid out on a flower-decorated tray brought home from a tour trip to socialist Hungary—cilantro, dill, parsley, collectively known as “the vitamins.” Crunchy homemade pickles, reminders of hot August days made even hotter by the water boiling in a giant aluminum pot, to sterilize the three-liter pickle jars. Transparent slabs of shredded chicken in aspic, trembling at the touch of a fork. In the oven, roast meat à la France: beef cutlets baked with onions, grated cheese, and mayonnaise. In the fridge, the ten-layer Napoleon cake, a six-hour-marathon-baking affair, taking half an hour per layer, preparation and chilling time not included (nor mayonnaise).

There was Champagne for the adult guests whom Mother had started hosting once going to Grandfather’s for the holidays was no longer an option. For the kids, there was sweet and strongly-carbonated foreign Pepsi-Cola, brewed at one of those “licensed plants” that our Communist leaders had negotiated, inexplicably, with the imperialists. Only one thing in the world tasted better than salad Olivier, and that was Olivier washed down with Pepsi. It was a Marxian dialectic: mayonnaise Provençal and Pepsi-Cola—each a quintessential symbol of the two irreconcilable ideological systems, fused in our mouths to trigger a burst of Soviet happiness hormones. More salad Olivier, anyone? Champagne? Pepsi?

The TV station beamed holiday shows with whimsical names that, for once, had nothing to do with building socialism, like “The Little Blue Flame,” or “Brasserie Twelve Chairs,” where famous men and women sat beside their holiday tables decorated by small New Year trees, artificial snow sparkling on plastic branches. Jokes called out across the room, tinsel streaming from the ceiling like silver rain, champagne bottles popping on both sides of the screen. At about 11 PM, the New Year fever would intensify. Dancing stopped, toasts became hurried, and everyone kept glancing at the clock. As another year in the “country of workers and peasants” wound to an end, our Leader addressed us briefly from the TV screen. Once he was done, the volume was turned back up, and everyone’s eyes were glued to the giant clock on Kremlin’s Spasskaya Tower.

If you wanted something badly, New Year’s Eve was your chance to wish for it. But for your wish to come true, you had to think it exactly when the Spasskaya Clock struck midnight. The pathos-filled trio of Kremlin chimes signaled the countdown. A fresh bottle of Champagne had to be opened at the first loud bhom and poured into glasses around the room. Those who had been smoking on the balcony would be summoned back into the living room. Those still in the kitchen would bring whatever they were spreading, arranging, and mixing, and get their refilled glasses. Even the kids would be offered a splash of Champagne. Family members would be exhorted to gather closer to one other. Seven, everyone counted. Eight! Nine! Ten!

Throughout the years, my wish never changed, even though it stubbornly refused to come true. It was true that I never liked the few boyfriends that my mother had, save for that one classmate she should have married instead of my father. And it was true that in this patriarchal southern town, few men could handle a woman like my mother. Her predicament, her lonely quest for our survival, her sewing skirts in exchange for jars of mayonnaise with other struggling women, were as inexorable as the movement of time, signaled by the strikes of the Kremlin clock. But this was New Year’s Eve, the one day in the USSR when hope trampled reason. Eleven! Twelve!

Let my mother get married.

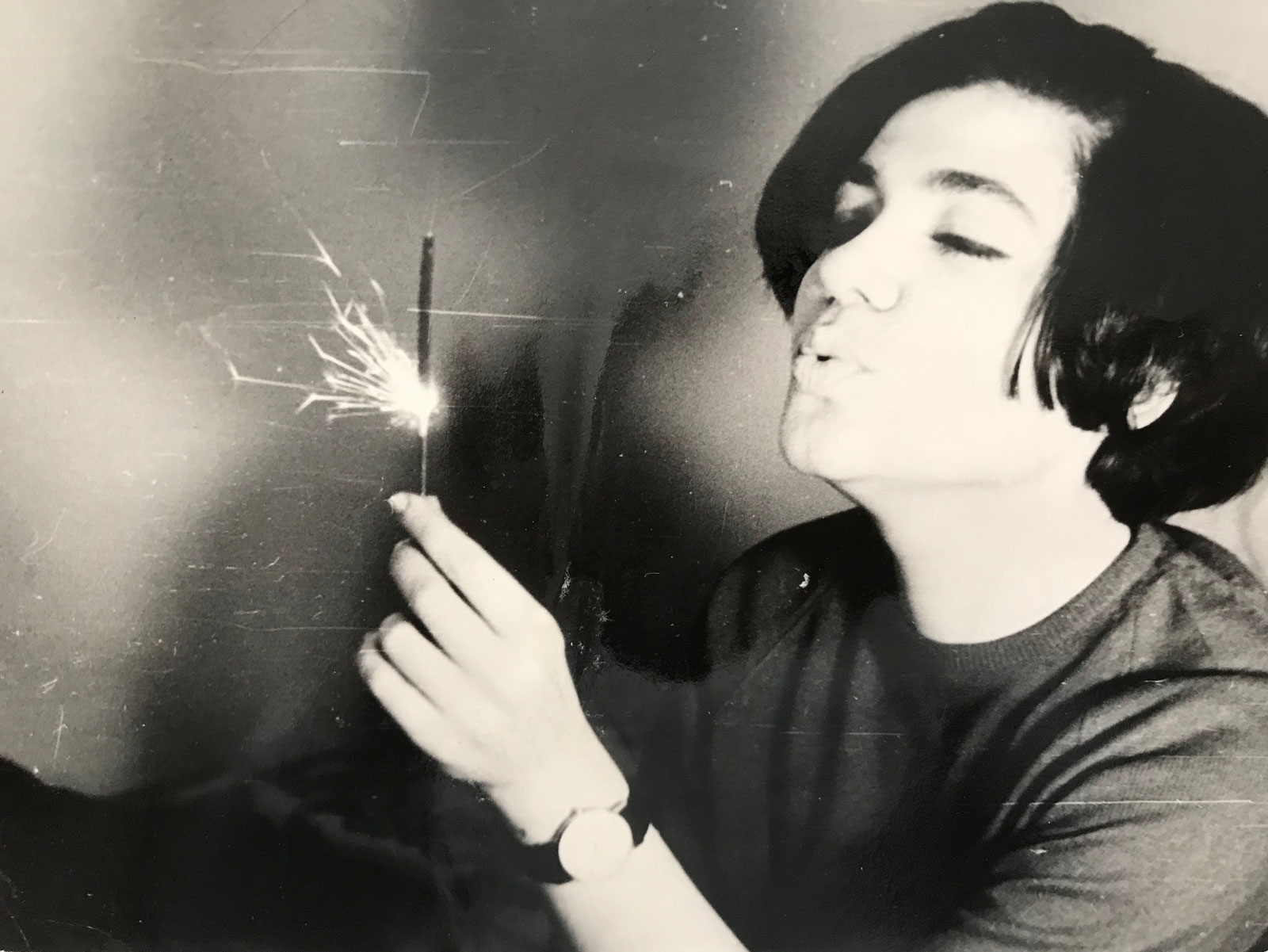

Happy New Year! Serpentine rings of streamers uncoiling in colorful spirals over the table, confetti falling into the empty Olivier bowl and over the half-eaten herring-under-a-fur coat. A smell of sulphur from the “Bengal Fire” sparklers showering silver arrows over my hand without burning it. Homemade rockets crisscrossed the sky with loud whistles, and people on the balconies called out holiday good wishes to those in the apartment building across the way. Mother’s kiss on my cheek, the elusive scent of Miss Dior, then the smell of Turkish coffee wafting from the kitchen. The Napoleon cake, now being cut, would be eaten before the New Year was barely an hour old, and that year, we hoped, would be better than the one that came before. Once a year, the Soviet people had the right to be hopeful. And so we were. The mayonnaise helped.