The planet has been knocked off its elliptical orbit and overheats as it hurtles toward the sun; the night ceases to exist, oil paintings melt, the sidewalks in New York are hot enough to fry an egg on, and the weather forecast is “more of the same, only hotter.” Despite the unbearable day-to-reality of constant sweat, the total collapse of order and decency, and, above all, the scarcity of water, Norma can’t shake the feeling that one day she’ll wake up and find that this has all been a dream. And she’s right. Because the world isn’t drifting toward the sun at all, it’s drifting away from it, and the paralytic cold has put Norma into a fever dream.

This is “The Midnight Sun,” my favorite episode of The Twilight Zone, and one that has come to seem grimly familiar. I also wake up adrift, in a desperate and unfamiliar reality, wondering if the last year in America has been a dream—I too expect catastrophe, but it’s impossible to know from which direction it will come, whether I am right to trust my senses or if I’m merely sleepwalking while the actual danger becomes ever-more present. One thing I do know is that I’m not alone: since the election of Donald Trump, it’s become commonplace to compare the new normal to living in the Twilight Zone, as Paul Krugman did in a 2017 New York Times op-ed titled “Living in the Trump Zone,” in which he compared the President to the all-powerful child who terrorizes his Ohio hometown in “It’s a Good Life,” policing their thoughts and arbitrarily striking out at the adults. But these comparisons do The Twilight Zone a disservice. The show’s articulate underlying philosophy was never that life is topsy-turvy, things are horribly wrong, and misrule will carry the day—it is instead a belief in a cosmic order, of social justice and a benevolent irony that, in the end, will wake you from your slumber and deliver you unto the truth.

The Twilight Zone has dwelt in the public imagination, since its cancellation in 1964, as a synecdoche for the kind of neat-twist ending exemplified by “To Serve Man” (it’s a cookbook), “The After Hours” (surprise, you’re a mannequin), and “The Eye of the Beholder” (everyone has a pig-face but you). It’s probably impossible to feel the original impact of each show-stopping revelation, as the twist ending has long since been institutionalized, clichéd, and abused in everything from the 1995 film The Usual Suspects to Twilight Zone-style anthology series like Black Mirror. Rewatching these episodes with the benefit of Steven Jay Rubin’s new, 429-page book, The Twilight Zone Encyclopedia, (a bathroom book if ever I saw one), I realized that the punchlines are actually the least reason for the show’s enduring hold over the imagination. That appeal lies, rather, in its creator Rod Serling’s rejoinders to the prevalent anti-Communist panic that gripped the decade: stories of witch-hunting paranoia tend to end badly for everyone, as in “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street,” in which the population of a town turns on each other in a panic to ferret out the alien among them, or in “Will the Real Martian Please Stand Up?” which relocates the premise to a diner in which the passengers of a bus are temporarily stranded and subject to interrogation by a pair of state troopers.

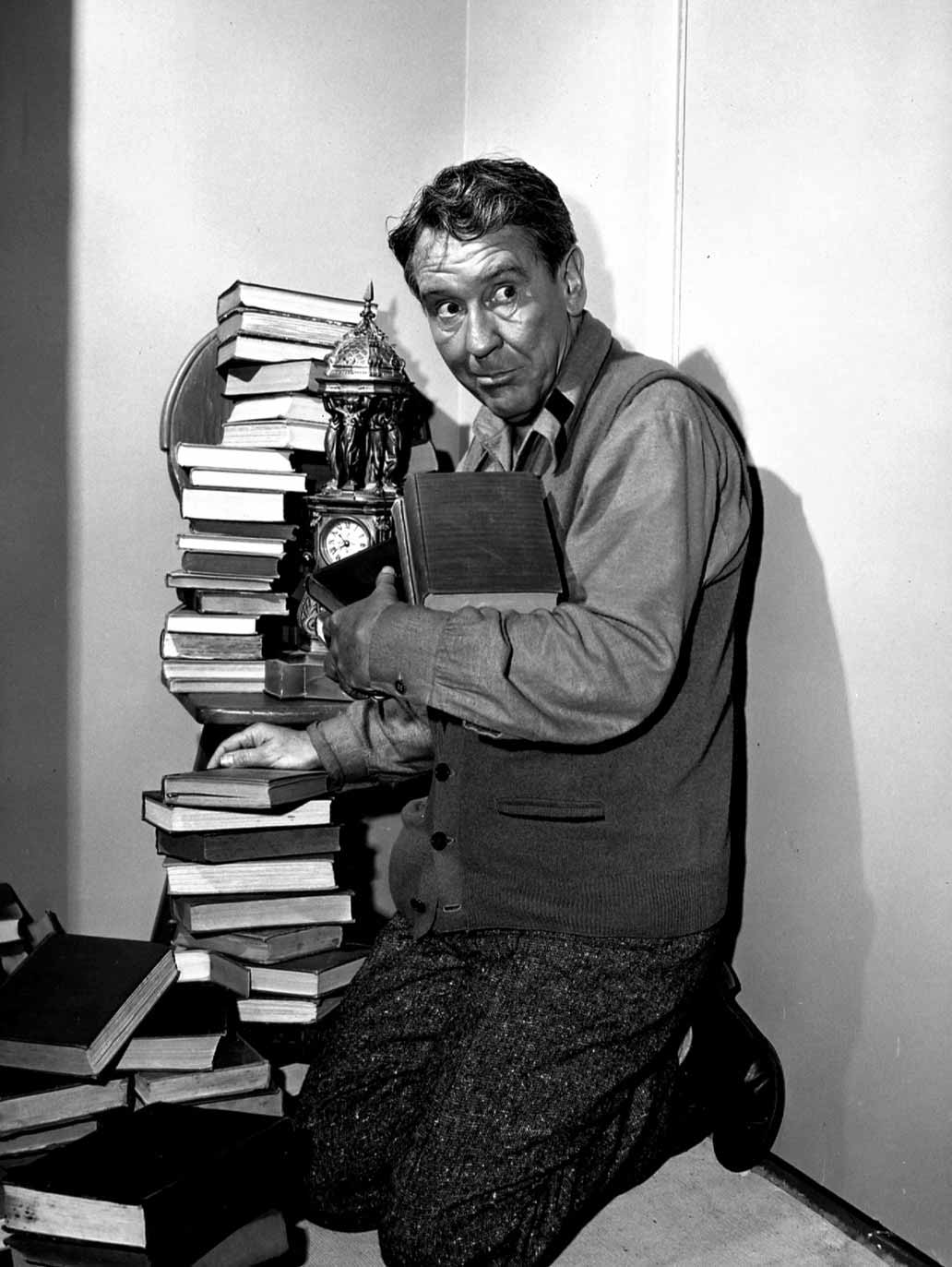

The show’s most prevalent themes are probably best distilled as “you are not what you took yourself to be,” “you are not where you thought you were,” and “beneath the façade of mundane American society lurks a cavalcade of monsters, clones, and robots.” Serling had served as a paratrooper in the Philippines in 1945 and returned with PTSD; he and his eventual audience were indeed caught between the familiar past and an unknown future. They stood dazed in a no-longer-recognizable world, flooded with strange new technologies, vastly expansionist corporate or federal jurisdictions, and once-unfathomable ideologies. The culture was shifting from New Deal egalitarianism to the exclusionary persecution and vigilantism of McCarthyism, the “southern strategy” of Goldwater and Nixon, and the Cold War-era emphasis on mandatory civilian conformity, reinforced across the board in schools and the media. In “The Obsolete Man,” a totalitarian court tries a crusty, salt-of-the-earth librarian (played by frequent Twilight Zone star Burgess Meredith, blacklisted since the 1950s, who breaks his glasses in “Time Enough At Last” and plays the titular milquetoast in “Mr. Dingle, the Strong”), who has outlived his bookish medium; but his obsolescence is something every US veteran would have recognized given the gulf between the country they defended and the one that had so recently taken root and was beginning to resemble, in its insistence on purity and obedience to social norms, the fascist states they had fought against in the war. From Serling’s opening narration:

Advertisement

You walk into this room at your own risk, because it leads to the future, not a future that will be but one that might be. This is not a new world, it is simply an extension of what began in the old one. It has patterned itself after every dictator who has ever planted the ripping imprint of a boot on the pages of history since the beginning of time. It has refinements, technological advances, and a more sophisticated approach to the destruction of human freedom. But like every one of the superstates that preceded it, it has one iron rule: logic is an enemy and truth is a menace.

The show’s subversive credentials —buoyed by semi-satirical “soft” science fiction writers like Richard Matheson, Damon Knight, and Ray Bradbury—is one of the secret threads running through Rubin’s Encyclopedia, which logs each episode’s opening monologue, premise, and cast along with behind-the-scenes production notes. The book is so absurdly comprehensive, you start to pick up on the eerie synergy between the show and its personnel, who often come to bad ends or survive by uncanny close-calls. A particularly savage case is that of Gig Young, who played the advertising executive trapped in a bucolic small town nightmare in “Walking Distance,” and who in real life murdered his wife before turning the gun on himself in 1978. Or Cliff Robertson, the ventriloquist in 1962’s “The Dummy,” whose original flight to Hollywood to film the episode crashed into Jamaica Bay after he changed his reservation, and who also happened to be flying his own twin-engine airplane over New York City on the morning of September 11, 2001. The effect is to render The Twilight Zone in a new light, as a realist television show that was simply the first to grasp that life itself is outlandish, more horrific and strange than a million Martian landscapes.

And then there’s the remarkable case of Charles Beaumont, the most prolific and celebrated of the show’s writers next to Sterling. At the time of his death at thirty-eight in 1967, he physically resembled a man of ninety years old, having abruptly aged into unrecognizable infirmity—due, depending on whom you ask, to a unique combination of Alzheimer’s and Pick’s Disease, or an addiction to Bromo-Seltzer, a shady over-the-counter antacid and hangover cure that was withdrawn from the market in 1975 due to toxicity. Beaumont was credited with twenty-two episodes of The Twilight Zone, including “Living Doll,” “Number 12 Looks Just Like You,” and “The Howling Man,” the last adapted from one of his many short stories (collected by Penguin Classics in 2015, with an afterword by William Shatner). While Serling’s Twilight Zone scripts tended to concentrate on supernatural reversals of social norms or the just deserts of assorted pretenders, reactionaries, and bigots, Beaumont’s topics trafficked in existential despair, returning to themes of futility and isolation. A man on death row is caught in a cyclical dream where the stay of execution always arrives too late (“Shadow Play”); a lonely man can only function inside the fantasies taking place inside a dollhouse (“Miniature”); a dead man quickly tires of Heaven (“A Nice Place to Visit”); and in “Printer’s Devil,” a beleaguered small-town publisher, despairing of the death of print in 1963, more-or-less-knowingly hires the Devil as his new linotype operator (Burgess Meredith again). Charles Beaumont’s cultural contribution might, in other words, be termed the most salient and pitch-black representations of irony-in-action to have graced the small screen when The Twilight Zone began airing on CBS in 1959. More than any writer up to that point, Beaumont discovered an intersection between pulp fare and Sophocles, making sociopolitical morality plays out of dime-rack science fiction, a contribution—shared with Serling—without which contemporary pop culture, with its strong tendency to couch social commentary in a metaphysical vernacular borrowed from comics and monster movies, would be impossible to imagine.

The most fun to be had with The Twilight Zone Encyclopedia, aside from the archival joys of reading Rubin’s detailed biographies of cast members like George Takei, Charles Bronson, Peter Falk, Robby the Robot, Anne Francis, Billy Mumy (who played the aforementioned god-child Anthony Fremont in “It’s A Good Life” and went on to record the novelty song “Fish Heads” as an adult), and Burt Reynolds (doing a dead-on Marlon Brando in “The Bard,” in which William Shakespeare struggles as a television ghostwriter), is found in the entries for broadly generic themes like “Children,” “Aliens,” “Nostalgia,” “Eccentrics,” and “Monsters.” Each of these meditates on a given subject’s representation in the show, imparting a nutshell census of about a page and a half that both speaks to the varied depiction of, say, “Obsession” or “Disappearances,” and makes for perfect marathon binging-by-topic (a night devoted to “Spaceships,” for example, would have to include “The Invaders,” “Third From the Sun,” and “On Thursday We Leave For Home”). More telling is the entry for “Justice,” which reads:

Advertisement

Though networks of the period avoided tackling uncomfortable topics like the Holocaust in traditional television dramas, Serling often exploited his show’s fantasy milieu and allegorical approach to storytelling to evade the kind of censorship that constrained more realistic programs. CBS network programming head James Aubrey might complain that sponsors avoid such material like the plague—after all, how do you explore the Holocaust and then sell toilet paper or underarm deodorant?—but Serling always stuck to his guns.

The Twilight Zone was developed from a pilot by Serling, “The Time Element,” originally broadcast as an episode of Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse in 1958, and concerning a psychiatric patient who relives the attack on Pearl Harbor, unaware that he in fact perished in the bombings. Besides the other wartime fables like “A Quality of Mercy,” “King Nine Will Not Return” and “Deaths-Head Revisited,” in which an ex-Nazi is driven insane by the ghosts of Dachau, Serling demonstrated his intolerance for discrimination and right-wing ideologies in the all-black cast of “The Big Tall Wish,” the lynching story “I Am the Night—Color Me Black,” written in the immediate aftermath of JFK’s assassination, and “He’s Alive,” starring Dennis Hopper as an American Nazi, who, “like some goose-stepping predecessors… searches for something to explain his hunger, and to rationalize why a world passes him by without saluting.” The Encyclopedia’s entries on virtually all of these explicitly progressive episodes give an account of the political interference Serling faced from the network. In “handsome, arrogant, egotistical” station executive James Aubrey, he found his most tenacious adversary, who consistently shortchanged The Twilight Zone, which was never a sure thing in the ratings, for the likes of Gilligan’s Island and The Beverly Hillbillies. Serling also weathered significant public outcry: an editorial partially reprinted in the Encyclopedia accused the show of Communist sympathies and criticized “He’s Alive” by observing that “the speech of the young Nazi, in the purely political aspects, sounded a great deal more like Barry Goldwater, a man of Jewish lineage, than it did like Hitler.” Serling, who was born Jewish and converted to Unitarianism, responded with characteristically biting candor that:

[the far right seems] to feel that racism, bigotry and hatred should be of little consequence to us in view of the fact that communists are trying to take over our government, invade our schools, and subvert our institutions… But I submit that we have other enemies no less real, no less constant, and no less damaging to the fabric of a democracy. It’s when we hear denials that these people exist, and that their poison is being disseminated, and that any comment to the effect is irrelevant—I wonder if The Twilight Zone isn’t something more than a television idea.

Television idea or not, The Twilight Zone was an American idea, and one whose commitment to the ideals of equanimity, brotherhood, and social activism gave rise to satire at its most pointed and Juvenalian, disguised as a supernatural anthology series. Educated at the Ohio liberal arts college Antioch, Serling recalled in his last interview, before dying during heart surgery in 1975 the age of fifty, that he was motivated by his disgust at postwar bias and prejudice, which he railed against so virulently that he confessed “to creating daydreams about how I could… bump off some of these pricks.” But writing ultimately covers more ground, and Serling confined his daydreams to television and film (he famously co-wrote Planet of the Apes, another buffet of Cold War anxieties served up as an alternate-reality blockbuster).

It’s not quite the case that The Twilight Zone has been consistently influential since its early 1960s heyday. Instead, the anthology of “weird tales” format comes into vogue every fifteen years or so, with The Twilight Zone providing the obvious benchmark. Serling contributed to and hosted one of the first of these, Night Gallery, but rightly recognized that the new breed of shows abandoned the real spirit of The Twilight Zone in favor of cheap scares and special effects. Of its contemporary heirs, Black Mirror most resembles The Twilight Zone’s perception of technology as a tool for flattening the individual beneath the corrupting gullibility of the masses. But, with the exception of the very best episodes—such as the immediately canonized “San Junipero” and fourth season premiere “USS Callister,” both of which introduce simulated realities where disenfranchised members of society can dwell indefinitely—these current episodes are merely chilling visions of what already is, in which technology is the villain, not people. Serling, Beaumont, and the rest of the show’s contributors identified the enemies within: orthodoxy, demagoguery, and, above all, compromised conscience. It was for this reason that every opening monologue reminds us that The Twilight Zone is beyond the door of imagination, but not beyond us, lying “between the pit of man’s fears and the summit of his knowledge,” which is precisely the niche where politics ends and art begins.

Steven Jay Rubin’s The Twilight Zone Encyclopedia is published by the Chicago Review Press.