This is part of a series of occasional pieces reflecting on the tumultuous political events of 1968 and their legacy fifty years on.

Commemorations are the greeting cards that a sensation-soaked culture sends out to acknowledge that we, the living, were not born yesterday. So it is with this year’s media reassembly of 1968. What is hard to convey is the texture of shock and panic that seized the world a half-century ago. What is even harder to grasp is that the chief political victor of 1968 was the counter-revolution.

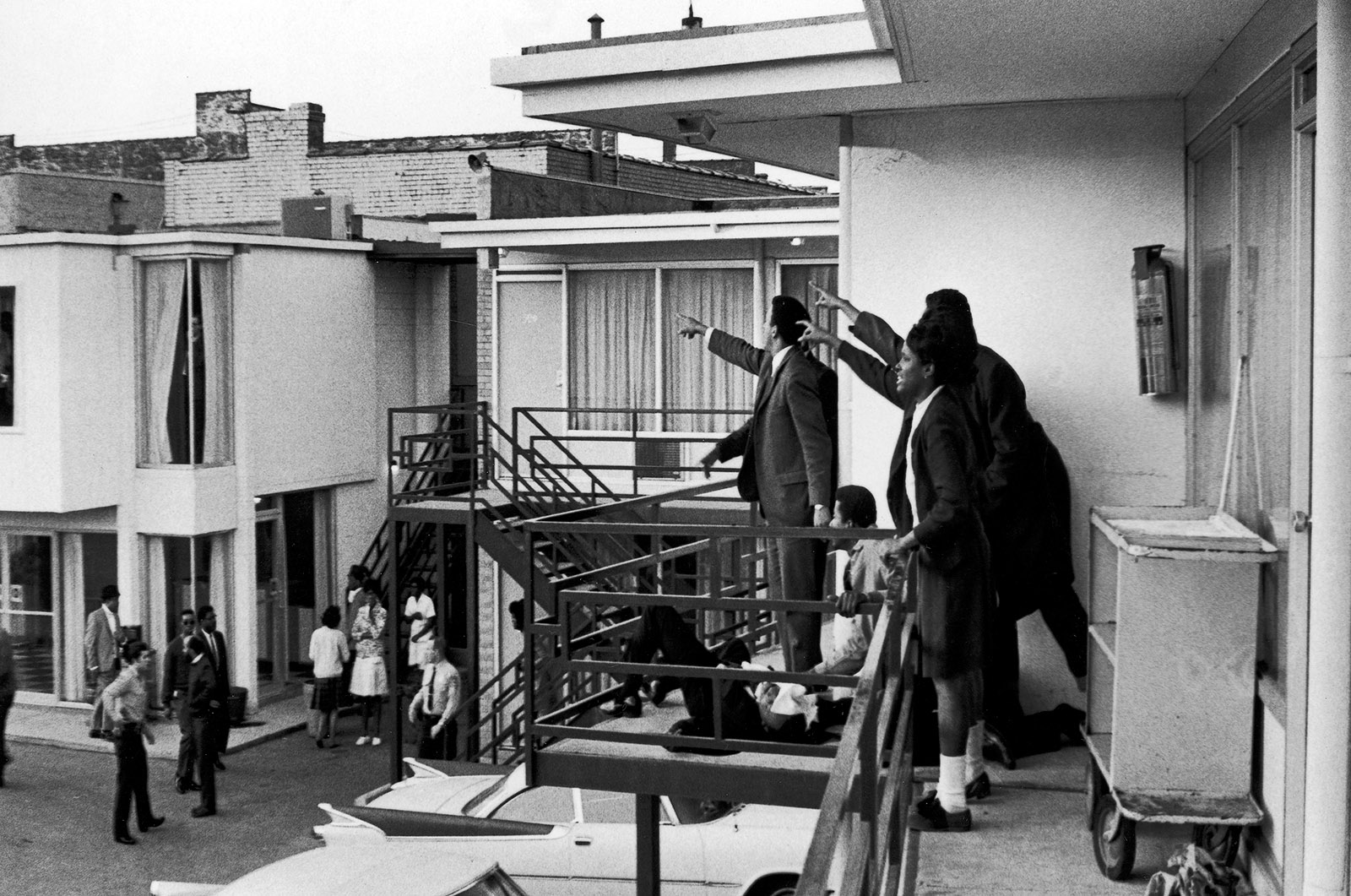

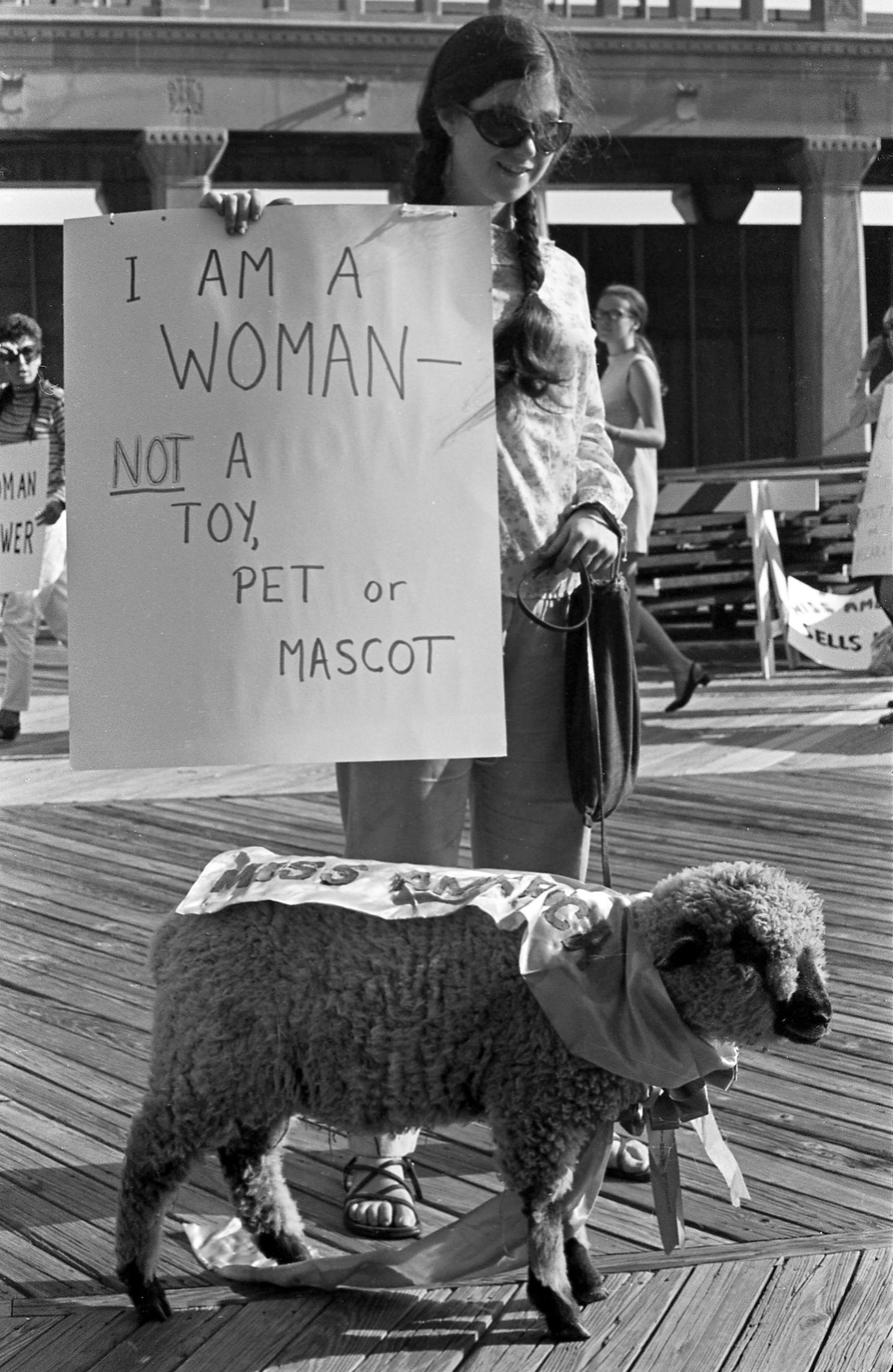

When we fight over the meaning of the past, we are fighting over what, today, we choose to care about. In this way, the 1968 anniversaries stalk 2018, depicting scene after scene of revolt, horror and cruelty, of fervor aroused and things falling apart, and overall, the sense of a gathering storm of apocalypse, even revolution. Inevitably, the “iconic” images of the time feature scenes of brutality, rebellion, and tragedy: a South Vietnamese general’s blowing out the brains of a prisoner on a Saigon street during the Tet Offensive; the Reverend Andrew Young Jr. and his colleagues, on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, next to the body of Martin Luther King Jr., pointing at where the assassin’s bullet had come from; demonstrators at Columbia taking over campus buildings, then hauled away, battered bloody by cops; Parisian protesters hurling tear gas canisters back at the police; Robert Kennedy felled by Sirhan Sirhan’s shots at the Ambassador Hotel; Soviet tanks rolling into Prague; police clubbing demonstrators at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago; women’s liberation activists dumping girdles, hair curlers, and bras (unburnt) in a trash can on the boardwalk outside Atlantic City’s Miss America pageant; Tommy Smith and John Carlos on the Olympic medalists’ platform in Mexico City, raising their black-gloved fists in defiance.

A more thorough survey would take note of social collisions that, however violently repressive, failed to register in America with the same supersaturated significance. For example: the killing of three students in Orangeburg, South Carolina, by highway patrol officers after the students protested segregation at a bowling alley (February 8); the near-deadly shooting of the German radical student leader Rudi Dutschke in Berlin (April 11); Chicago police battering a wholly nonviolent antiwar protest (April 27).

As for less bloody demonstrations, there were so many, so routinely, that The New York Times regularly grouped civil rights and antiwar stories on designated pages. Neither does this rundown of calamities take into account images that did not see the light of day until much later, like the color shots of the My Lai massacre (March 16), not published until late 1969—by which time they were almost expected. Or the images that never materialized at all, like the slaughter of hundreds of demonstrating students by troops in Mexico City (October 2).

Images aside, what was it really like to experience 1968? Public life seemed to become a sequence of ruptures, shocks, and detonations. Activists felt dazed, then exuberant, then dazed again; authorities felt rattled, panicky, even desperate. The world was in shards. What were for some intimations of a revolution at hand were, for exponents of law and order, eruptions of the intolerable. Whatever was valued then appeared breakable, breaking, or broken.

The texture of these unceasing shocks was itself integral to what people felt as “the 1968 experience.” The sheer number, pace, volume, and intensity of the shocks, delivered worldwide to living room screens, made the world look and feel as though it was falling apart. It’s fair to say that if you weren’t destabilized, you weren’t paying attention. A sense of unending emergency overcame expectations of order, decorum, procedure. As the radical left dreamed of smashing the state, the radical right attacked the establishment for coddling young radicals and enabling their disorder. One person’s nightmare was another’s epiphany.

The familiar collages of 1968’s collisions do evoke the churning surfaces of events, reproducing the uncanny, off-balance feeling of 1968. But they fail to illuminate the meaning of events. If the texture of 1968 was chaos, underneath was a structure that today can be—and needs to be—seen more clearly.

The left was wildly guilty of misrecognition. Although most on the radical left thrilled to the prospect of some kind of revolution, “a new heaven and a new earth” (in the words of the Book of Revelation), the main story line was far closer to the opposite—a thrust toward retrogression that continues, though not on a straight line, into the present emergency. The New Deal era of reform fueled by a confidence that government could work for the common good was running out of gas. The glory years of the civil rights movement were over. The abominable Vietnam War, having put a torch to American ideals, would run for seven more years of indefensible killing.

Advertisement

The main new storyline was backlash. Even as President Nixon assumed a surprising role as environmental reformer, white supremacy regrouped. Frightened by campus uprisings, plutocrats upped their investments in “free market” think tanks, university programs, right-wing magazines, and other forms of propaganda. Oil shocks, inflation, and European and Japanese industrial revival would soon rattle American dominance. What haunted America was not the misty specter of revolution but the solidifying specter of reaction.

Even as established cultural authorities were defrocked, political authorities revived and entrenched themselves. In so many ways, the counterculture, however domesticated or “co-opted” in Herbert Marcuse’s term, became the culture. Within a few years, in public speech and imagery, in popular music and movies, on TV (All in the Family, M*A*S*H, The Mary Tyler Moore Show) and in the theater (Hair, Oh! Calcutta!), profanity and obscenity taboos dissolved. Gays and feminists stepped forward, always resisted but rarely held back for long. It would subsequently be, as the gauchistes of May ’68 in Paris liked to say, forbidden to forbid.

In the realm of political power, though, for all the many subsequent social reforms, 1968 was more an end than a beginning. After les évènements in France in May came June’s parliamentary elections, sweeping General De Gaulle’s rightist party to power in a landslide victory. After the Prague Spring and the promise of “socialism with a human face,” the tanks of the Soviet-run Warsaw Pact overran Czechoslovakia. In Latin America, the Guevarist guerrilla trend was everywhere repulsed, to the benefit of the right. In the US, the “silent majority” roared. As the divided Democratic Party lay in ruins, Richard Nixon’s Southern strategy turned the Party of Lincoln into the heir to the Confederacy. As the right consolidated around an alliance of Christian evangelicals, racial backlashers, and plutocrats, the left was unable, or unwilling, to fuse its disparate sectors. The left was maladroit at achieving political power; it wasn’t even sure that was its goal.

Counter-revolutions, like their revolutionary bêtes noires, suffer reversals and take time to cohere. The post-1968 counter-revolution held the fort against a trinity of bogeymen: unruly dark-skinned people, uppity women, and an arrogant knowledge class. In 1968, it was not yet apparent how impressively the recoil could be parlayed into national power. “This country is going so far to the right you won’t recognize it,” Nixon’s attorney general, John Mitchell, said in 1969. He spoke prematurely.