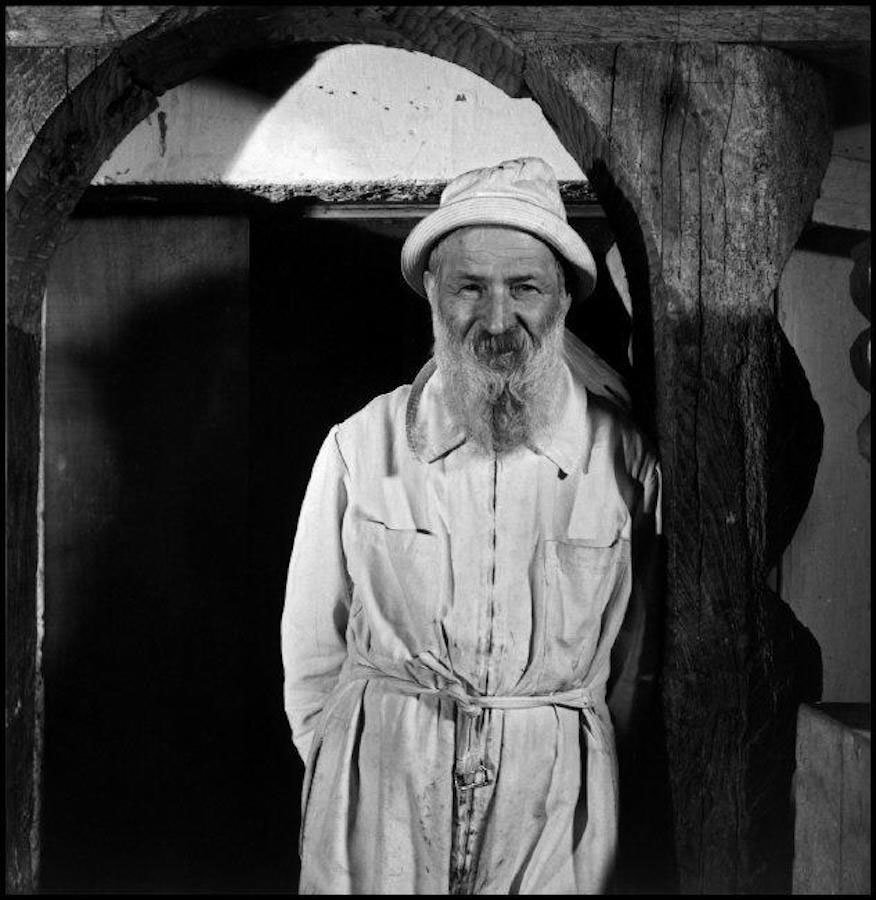

Few artists encapsulate the story of the early twentieth-century avant garde more alluringly than Constantin Brancusi. The son of Romanian peasants, he arrived in Paris around the same time Picasso did, but on foot. Within a few years, he had somehow managed to apprentice with Rodin. Then, throwing out the master’s methods, he completely redefined what sculpture was. Cultivating an image as a black-bearded ascetic, he wore simple white clothes, lived alone, and cooked his own food on the home-made stove of his back-alley Montparnasse atelier, while turning his favorite subjects—birds, fish, and a remarkable string of aristocratic women—into stupefyingly beautiful abstractions in polished marble or sleek bronze.

For years, Brancusi made hardly enough money to eat. In 1926, a version of one of his most extraordinary subjects, Bird in Space, was famously held up at the US border because customs officials didn’t think it was art. Sometimes, he even baffled his own cohort. Picasso (or perhaps Matisse) is said to have likened Brancusi’s 1916 Princess X, a glistening bronze torso of Princess Marie Bonaparte, to a large phallus. Yet, by the time of his death in 1957, the increasingly reclusive Romanian was regarded as one of the century’s greatest sculptors. (Peggy Guggenheim, who began buying his work in the 1940s and took artist-worship seriously, called him “half astute peasant and half real god.”) In recent years, he has been credited with paving the way for everything from mid-century abstract art to the postwar minimalists. And though he spent his entire life without a regular art dealer, he has finally conquered the art market as well: last year, a bronze version of his Sleeping Muse from 1913 sold for a staggering $57 million at Christie’s; that was quickly eclipsed this May, when a polished brass 1932 cast of La Jeune Fille Sophistiquée, his buoyantly curlicued “portrait” of British heiress and Montparnasse acolyte Nancy Cunard, sold for $71 million.

How to account for such a trajectory? This summer, two small New York shows—at the Museum of Modern Art and at the Guggenheim Museum—invite us to revisit Brancusi’s singular legacy. Both comprise objects from the museums’ own collections, and this is no accident. Though he spent almost all of his long career in Paris—working through two world wars he barely seems to have noticed—New York played an unusually large part in his story. According to the standard mythology, it was at the Armory Show in 1913 that Brancusi first exploded onto the international scene. His earliest and most important patron was a New Yorker. And by the final years of Brancusi’s life, top American museums were in intense competition for his work. “Without the Americans, I would not have been able to produce all this or even to have existed,” he said in 1955.

Featuring just eleven sculptures, the MoMA exhibition offers an elegantly concise introduction to Brancusi’s art. Included here are the early, totemic Maiastra (1910–1912), a long-necked mythical bird in white marble perched atop a column-like carved limestone pedestal; two different bronze renditions of his Bird in Space (1928 and 1941), and a seven-foot-tall 1918 oak version, the earliest that has survived, of his signature mature work, Endless Column. With the exception of Endless Column, which rises directly from the floor, all of the sculptures sit on Brancusi’s own bases. These wonderfully differentiated carved blocks, often in contrasting materials, he regarded as essential parts of the overall composition. (The pedestal of MoMA’s version of Maiastra actually incorporates a second sculpture, his Double Caryatid of 1908.)

What emerges here and in the Guggenheim’s display is the extent to which Brancusi was operating wholly outside the temper of his time, including the radical currents then stirring in Paris. Even a century later, a bronze version of the notorious Mlle Pogany—the tilted, bug-eyed, ovoid bust that, in classical white marble, so flummoxed visitors to the 1913 Armory Show—conveys much of the original strangeness of his approach. A depiction of his Hungarian muse, Margit Pogany, the piece cheerfully subverts everything portraiture was supposed to be, with facial features reduced to bewitching punctuation marks in an otherworldly but uncannily unified form. “He has thrown representation entirely overboard,” his first patron, the maverick New York lawyer John Quinn, observed at the time. “But he goes for effect, rhythm and force, not for realism or representation or resemblance.”

Within a few years, Brancusi had reduced descriptive features even further in works like The Newborn (1915), a streamlined ovoid mass that is hauntingly primal. Above all was his attention to form and surface, in uncompromising pursuit of the essence of his subjects and their movement in light and space. “What a pity it would be to spoil this beautiful material by digging into it little holes for eyes, hair, ears,” he retorted to a French journalist who asked about his controversial Princess X. “And my material is so beautiful in its sinuous lines which shine like pure gold and which embody in a sole archetype all the feminine effigies on this earth.”

In the MoMA show, this kind of reduction can best be observed in his bird sculptures, such as Young Bird (1928), which, while utterly avian in its small plump perched mass, is no longer defined by external features or appendages. The most spectacular work in this vein is his gorgeously aeriform Bird in Space (1928). A slender, light-catching polished bronze projection that lances into the sky from its cylindrical stone pedestal, this was the work that, in another rendition, US customs officials classified under “Kitchen Utensils and Hospital Supplies” and subjected to a heavy import tax for commercial goods. Brancusi was a “wonderful polisher of bronze,” they allowed, but that hardly made him an artist. (After a protracted lawsuit, with testimony from Brancusi’s friend Edward Steichen and other supporters, the judge grudgingly conceded that, though the object didn’t resemble a bird, it was “nevertheless pleasing to look at” and might be considered “art” by some.)

Along with the oaken Endless Column, there are two other examples in the MoMA show of his work in wood. One is the playful Socrates (1922), a precariously top-heavy construction that may be a portrait of his friend the composer Erik Satie (they referred to each other as Socrates and Plato). More interesting, however, is Cock (1924), his remarkably compressed evocation of a rooster in cherry wood, which, as the late curator Carolyn Lanchner observed in her brief guide to MoMA’s Brancusi collection, shows the extraordinary “visual mnemonics” he was able to deploy. “A flash of recognition converts this elegant abstract sculpture into a likeness of the king of the barnyard,” she writes.

More of Brancusi’s large-scale wood sculptures are on view in the small Guggenheim exhibition, which is artfully arranged in one of the museum’s tower galleries. The highlights here are Adam and Eve (1921) and the later King of Kings (1938), which seem to draw on such disparate sources as Romanian folk carving and African sculpture. For all that, it is hard not to be seduced by the Guggenheim’s 1912 Muse, a female head and neck in white marble (likely inspired by his friend, the French Baroness Renée-Irana Frachon), which shows the young sculptor already at the height of his powers. Here he was in radical pursuit of form and archetype, yet with the slightest articulations also managing to meld this to an almost classical sensibility.

In showing such choice pieces from their own collections, MoMA and the Guggenheim also provide insight into Brancusi’s American following. With a single exception, none of the works at either museum was acquired until the Fifties or later. It was also in that decade that both museums staged their first Brancusi exhibitions. This pattern held as well for the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the third great American center of his art, which acquired much of its large Brancusi collection, including Princess X, in that decade. (Peggy Guggenheim’s collection, which remained in her Venice palazzo, was first opened to the public in 1951.)

Indeed, the 1913 Armory Show, far from establishing a new public for Brancusi’s work, branded him—along with fellow provocateur Marcel Duchamp and the other “Cubistic” and “Modernistic” artists—as a symbol of all that was disturbing and “deranged” about modern art. For the next decade, his patron Quinn supported Brancusi virtually single-handedly, despite rapturous acclaim from fellow modernists such as Steichen and Ezra Pound (who was also on Quinn’s payroll). When Quinn died in 1924, there was so little American interest in his thirty-three Brancusis that Duchamp, together with Quinn’s art adviser and fellow Frenchman Henri-Pierre Roché, raised the money to buy them himself. Given the prevailing tastes, it’s little surprise that the US government mistook his work for high-luster kitchenware.

Advertisement

America’s eventual broad embrace of Brancusi had far less to do with his controversial pre-war exposure in the United States than with the mainstreaming of modern art in American culture after World War II. That the man who relentlessly reduced the material world to its purest forms is now not only a museum mainstay but a record-breaking emblem of conspicuous art-market consumption illustrates just how powerful, and strange, that turn has been.

“Constantin Brancusi Sculpture” is on view at the Museum of Modern Art through February 18, 2019. “Guggenheim Collection: Brancusi” is on view at the Guggenheim Museum.