Hidden among the chalk hills of East Sussex is Charleston, the sixteenth-century farmhouse and gardens that the Bloomsbury Group transformed into their most famous work of art. When Vanessa Bell signed the first of a series of long leases on the property in October 1916, she treated the house’s interior as a blank canvas. Murals and patterns were painted directly onto whitewashed walls, stripped doors, fireplaces, and bedsteads; even the wooden cladding around the bathtubs wasn’t off-limits for decoration.

Today, to visit Charleston—which has been open to the public since 1986, but has just launched its first exhibition and event spaces, along with a new restaurant—is to be transported back in time. Even the plants in the garden have been painstakingly chosen to replicate those from the house’s heyday within the three decades 1930–1959. Recognizing just how important color would have been to Vanessa and her fellow artists, Fiona Dennis, Charleston’s head gardener since 2017, sees it as her job “to capture the tone of the garden in its historic context.” The same verisimilitude continues inside the house, which feels as if the famous tenants are still in residence. In Vanessa’s downstairs bedroom, a straw hat lies on the bed as if discarded while she passed on her way in through the patio doors. The studio is full of evidence of her partner and sometime-lover Duncan Grant: the portrait of a muscled nude sits on an easel as if still drying; invitations are propped up amongst the objet d’art on the mantelpiece, while cuttings from newspapers, photographs and a child’s drawings are pinned below along the ledge; discarded paintbrushes and the like litter one of the corners of the room. One expects Vanessa’s husband, Clive Bell, to come sauntering into his book-lined study in search of a volume.

At the same time, there’s something a little uneasy about the site of such artistic and sexual experimentation, the home of people who pushed so forcefully against the establishment, having become a destination for day-trippers, complete with café and gift shop. Under Charleston’s modern guise as a tourist heritage site, it’s easy to overlook just how radically the members of the Bloomsbury Group lived their lives.

Dorothy Parker famously quipped that the cohort “lived in squares, painted in circles and loved in triangles.” Charleston played host to both the art and the love—much more so than the residences in Gordon and, thereafter, Fitzroy Square in London’s Bloomsbury. The group found respite from intolerance in this rural idyll. Vanessa and Grant transformed the house into a country outpost for their friends and family, a oasis of freedom and acceptance decades ahead of the social, moral, and aesthetic codes of the day. Theirs was a partnership grounded in the domestic rather than the erotic, though Grant was the father of Vanessa’s youngest child, Angelica. In grand Bloomsbury fashion, Angelica grew up to marry her father’s one-time lover, David Garnett, who’d lived at Charleston with Grant during World War I. As conscientious objectors, the two men contributed to the war effort by taking up farm tools instead of arms.

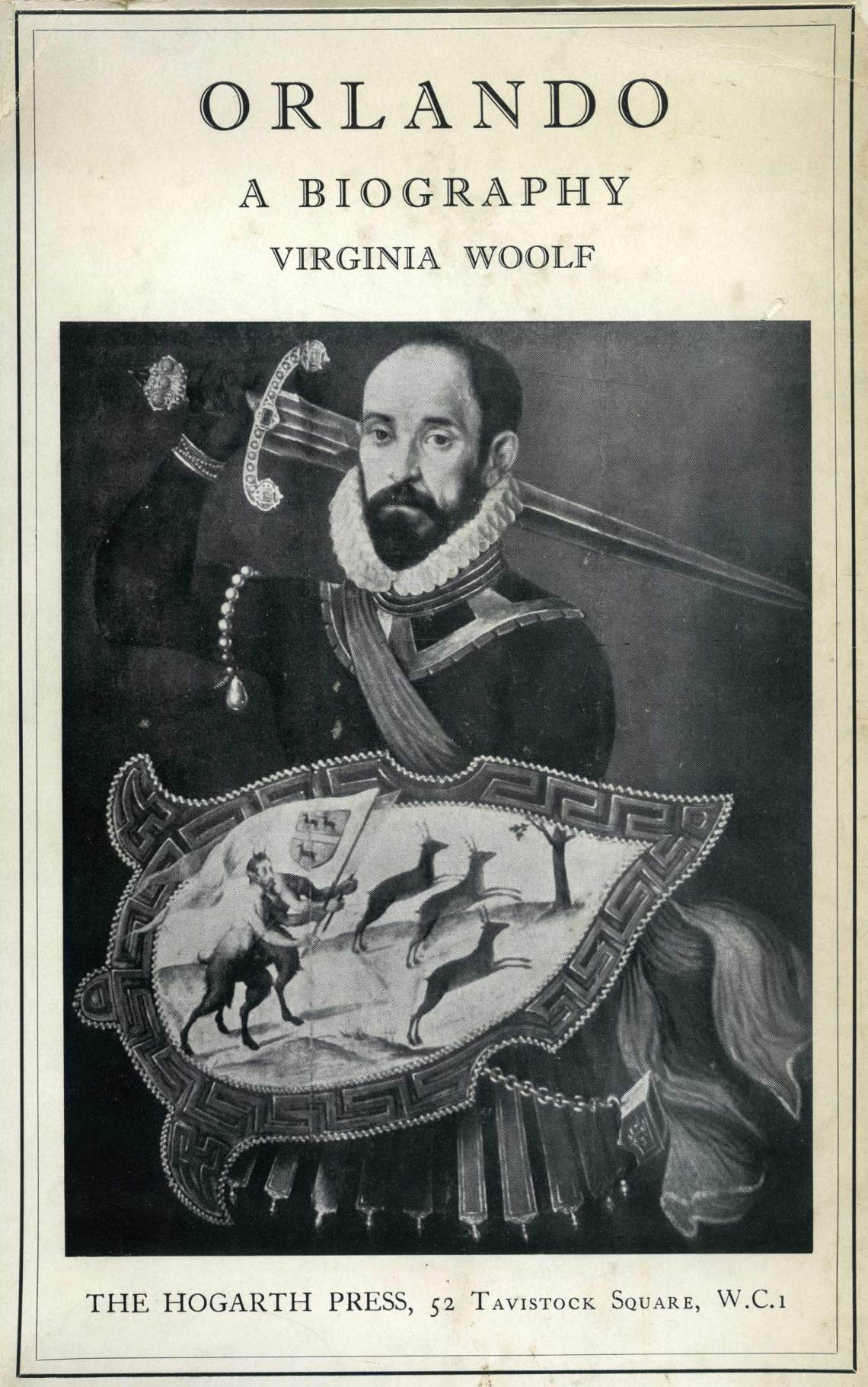

Then there was Vanessa’s sister Virginia Woolf’s famous relationship with Vita Sackville-West, a love affair that developed into a life-long friendship, and for whom Woolf wrote her enchanting 1928 novel, Orlando: A Biography, a historical romp about a poet who mysteriously changes sex from a man to a woman, and lives into the twentieth century, long after her birth during the reign of Elizabeth I. Both Virginia and Vita were Vanessa’s neighbors. After renting various houses in the area, in 1919 the Woolfs bought nearby Monk’s House, a seventeenth-century cottage that would be their country retreat—indeed, it was actually Virginia and Leonard who found Charleston for Vanessa, spying it one day while out walking—and it was in the local River Ouse that Virginia tragically drowned herself in 1941. While Sissinghurst Castle, where Vita lived with her husband Harold Nicolson, is only thirty-odd miles away in next door Kent. Celebrating the site’s queer history is a central tenet of the Charleston Trust’s manifesto today, so it’s only fitting that the new gallery space opened with an exhibition that commemorates the ninetieth anniversary of the publication of Woolf’s novel, regarded today as a staple of feminist and transgender studies.

Advertisement

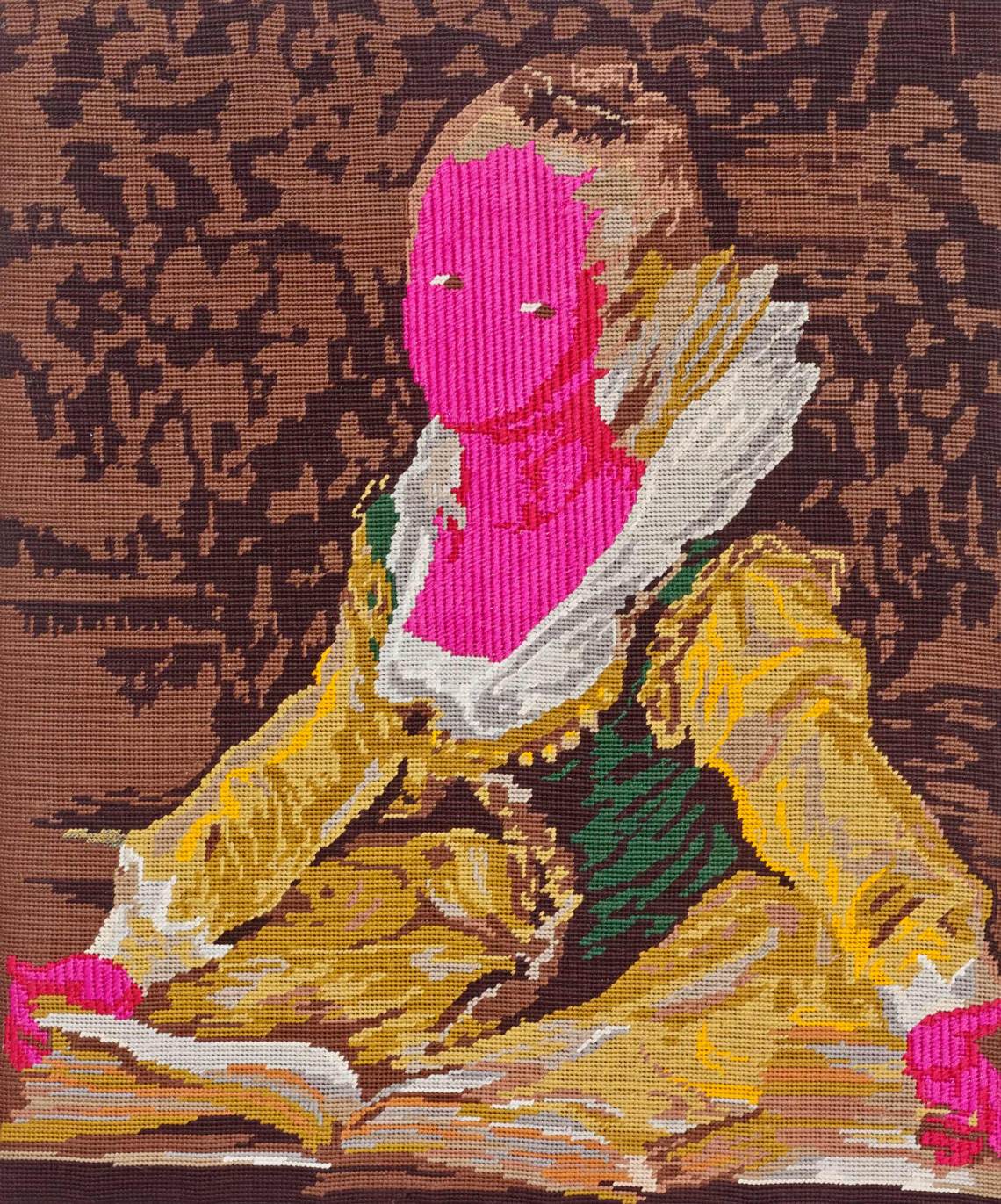

“Orlando…at the Present Time” is a small but surprisingly dense show. Seventeenth-century portraiture sits alongside modern needlepoint; a screen on one wall plays the Royal Ballet’s acclaimed 2015 Woolf Works production, while another across the room shows scenes from Sally Potter’s film adaptation of Orlando (1992), starring Tilda Swinton. The exhibition sets out to demonstrate the novel’s relevance today, but confusingly, it’s the pieces relating to the book’s historical background that prove the most engaging. Cornelius Nuie’s oil painting The Two Sons of Edward, 4th Earl of Dorset (circa 1642–1651), for example, shows Vita’s ancestors, the youngest of whom, Edward, was killed in the English Civil War, but whom Woolf brought back to life as the model for her young Orlando, conferring on him a fictional immortality. Then there is Vita’s mother Victoria’s annotated copy of the novel; she doesn’t mince her words about what she thinks of Woolf: “I loath [sic] this woman for having changed my Vita and taken her away from me.”

On close examination, many of the more modern artifacts are only tenuously linked to the source text. Yet it could be said that, in its eclecticism, curator Darren Clarke has achieved a magpie’s collection that is true to the flamboyance and invention of Woolf’s novel.

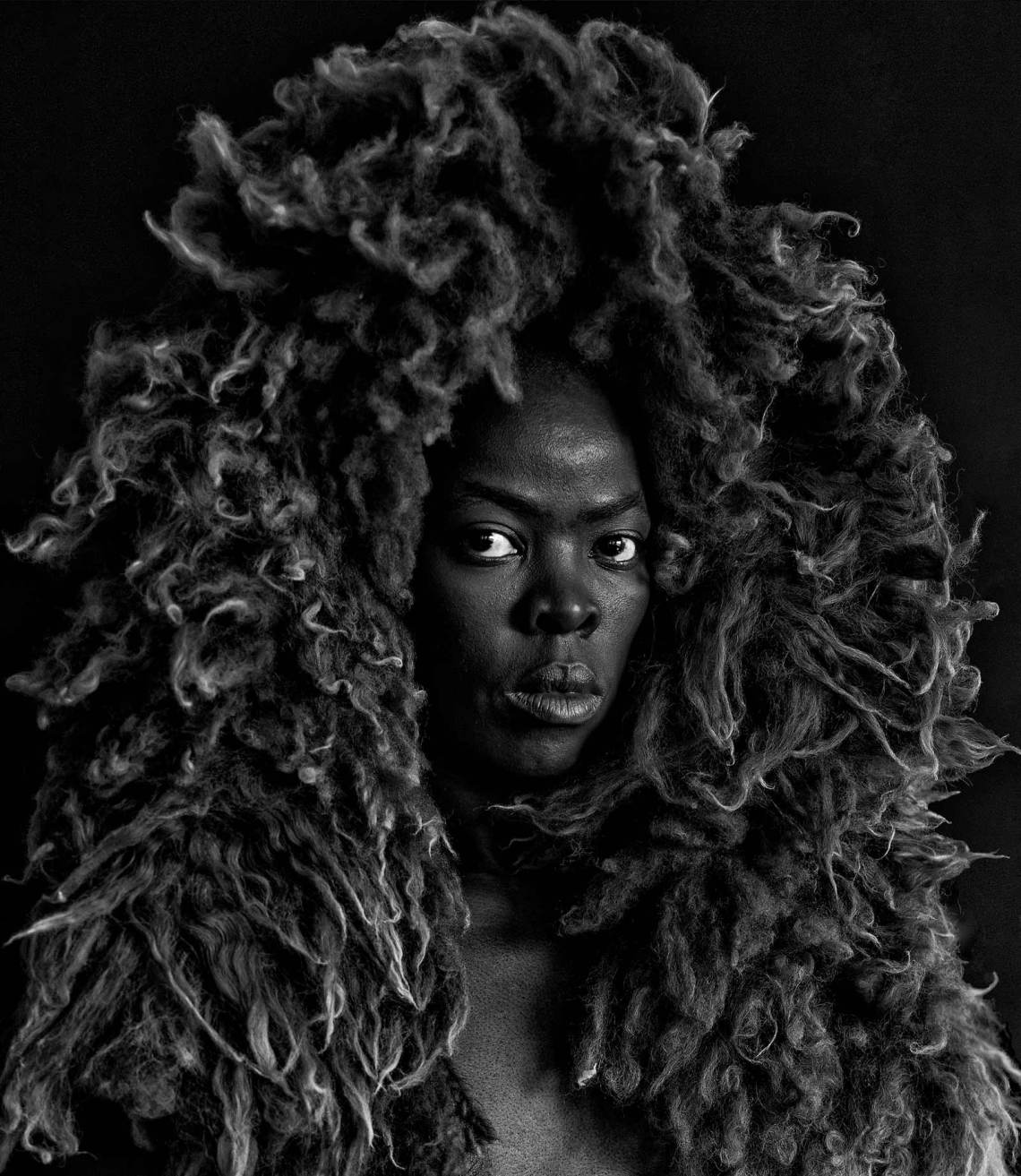

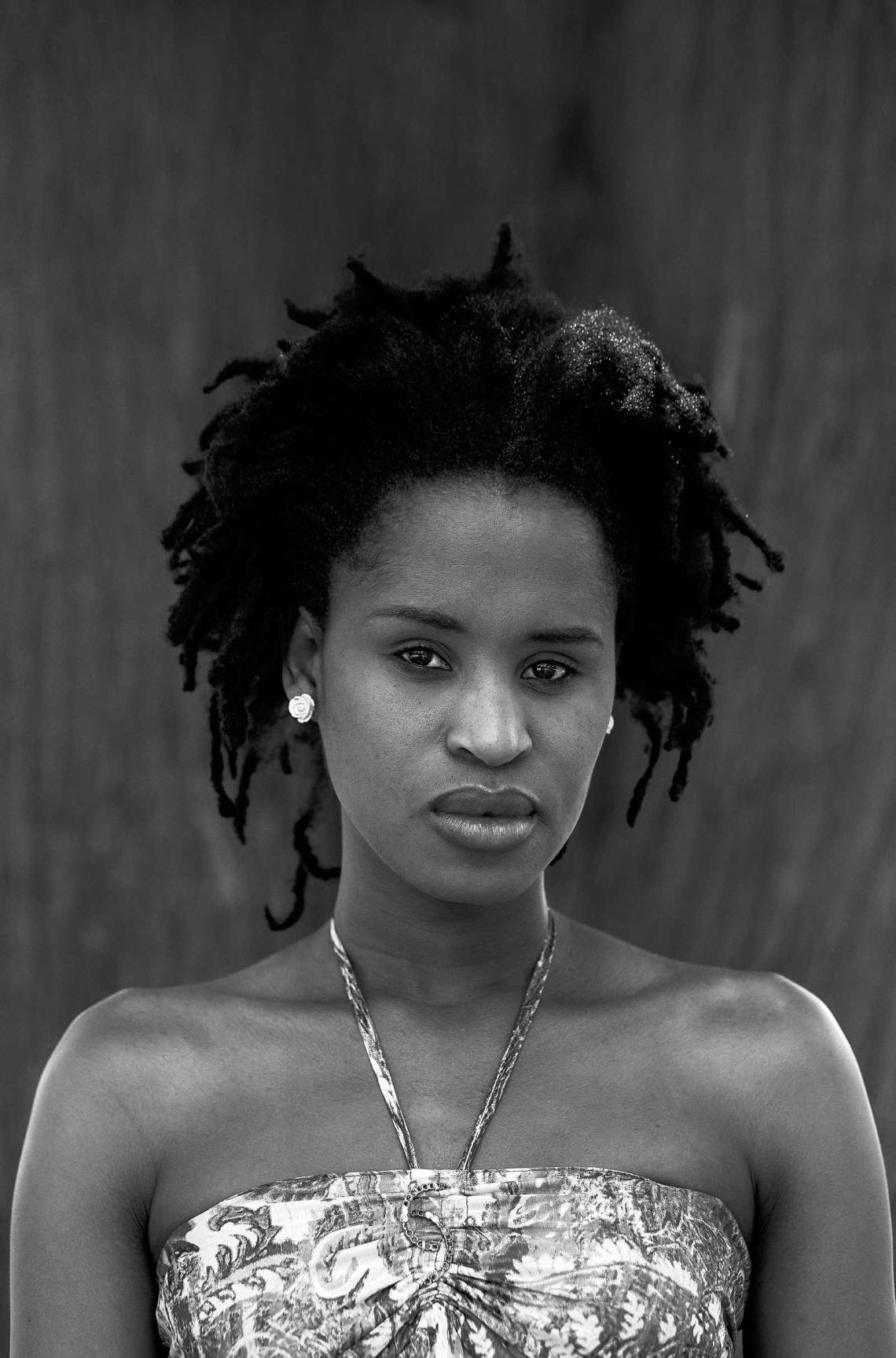

Gender fluidity is also the focus of Zanele Muholi’s “Faces and Phases”—the inclusion of which clearly demonstrates Charleston’s new mission to engage with the work of contemporary artists beyond those paying direct homage to the Bloomsbury Group. A series of beautiful black-and-white photographic portraits by Muholi show black lesbian, bisexual, trans, and intersex individuals living in South African townships where, despite liberal laws regarding same-sex marriage, discrimination and violence against the black LGBTQIA+ community is still widespread. The stark monochrome of Muholi’s photos sits in sharp contrast to the lush color palette on display in the Orlando exhibition in the room opposite, and her imposing portraits sit particularly well against the fresh white walls, exposed beamed ceiling above and brick floor below. Designed by Jamie Fobert Architects (also responsible for recent extensions at Tate St Ives, in Cornwall, and Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge), the compact, single-story new gallery has been constructed to complement the recently renovated farm building it sits alongside: two eighteenth-century conjoined barns, handsomely restored and redeveloped by Julian Harrap Architects into a cavernous events space and expanded restaurant.

Clearly, considerable effort has been made to establish a dialogue between Charleston’s past and present. Roger Fry, the renowned art critic and organizer of the pioneering Post-Impressionist exhibitions of 1910 and 1912, and the famous economist John Maynard Keynes were regular guests of Vanessa’s, the latter so frequently that he was given his own room, in which he wrote his most famous work, The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919). Occasional visitors included T. S. Eliot, E. M. Forster, Lytton Strachey, Benjamin Britten, and Peter Pears. No conversation was out of bounds at Charleston. It played host to as much lively debate as experimental artistic practice. Viewed as an annex of the original house, the new gallery allows for the display of contemporary work born of an avant-garde spirit similar to the Bloomsbury Group’s own artistic and intellectual endeavors.

Also on display is the stunning Famous Women Dinner Service, which the art historian and broadcaster Sir Kenneth Clark commissioned from Vanessa and Grant in 1932. Each plate in the hand-painted fifty-piece set depicts a famous woman, from Sappho to Greta Garbo, via Marie Antoinette, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and Flush, the poet’s beloved cocker spaniel (he could hardly be left out after Woolf had written his biography). It “ought to please the feminists,” Vanessa wrote to her friend Fry while she was working on the dinner set; indeed, it’s still a delight to look upon today, and as important a feminist project now as it was over eight decades ago. Admiring it now, one can’t help but think of Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party (1974–1979), her thirty-nine elaborate place settings arranged on a triangular table for mythical and historical female figures, which is on display in the Brooklyn Museum. Astonishingly, Chicago apparently conceived of the idea for her project long before she became aware of the Famous Women Dinner Service, which makes sense given Vanessa and Grant’s collection was never publicly displayed until now. For many years it disappeared without a trace.

Advertisement

The set was lost after being sold at auction in Germany by Clarke’s family following his death, and was only recently rediscovered after having been purchased by a private collector and brought back to England. So its return to Charleston—where it was created—is a celebratory homecoming, even though technically the Charleston Trust is still fundraising in order to keep the dining set there in its entirety as part of its permanent collection. They’re running an “adopt a plate” scheme, and those who’ve already donated include, amongst others, the Duchess of Cornwall (Jane Austen), Ali Smith (Virginia Woolf), Jeanette Winterson (Nell Gwynn), and Joanna Lumley (Ellen Terry). This seems to me where the new gallery can really come into its own. Although the set is very much a product of the house, to have displayed it there would have risked swamping the plates amid the surrounding decoration. In this new space, the dinner service appear in their full glory. It’s worth a visit to see them alone.

“Orlando…at the Present Time” and “Zanele Muholi: Faces and Phases” are on view at Charleston, Sussex, through January 6.