For most of his twenty-seven-year career in national politics, Jair Bolsonaro has been a fringe figure on the far right of Brazilian politics, hopping among nine different political parties and yelling his support for Brazil’s bygone military dictatorship into empty congressional chambers. All that has changed. Last weekend, the former army captain won over 46 percent of the vote in Brazil’s presidential race—close to an outright win in the first round. He goes forward to the run-off election on October 28 as the clear favorite.

Brazil has been a democracy with direct presidential elections since 1989, but for the preceding quarter-century it was ruled by a brutal military government. Bolsonaro is not merely nostalgic for that era; he would reintroduce the dictatorship’s political ethos, preserved and intact, into modern Brazil.

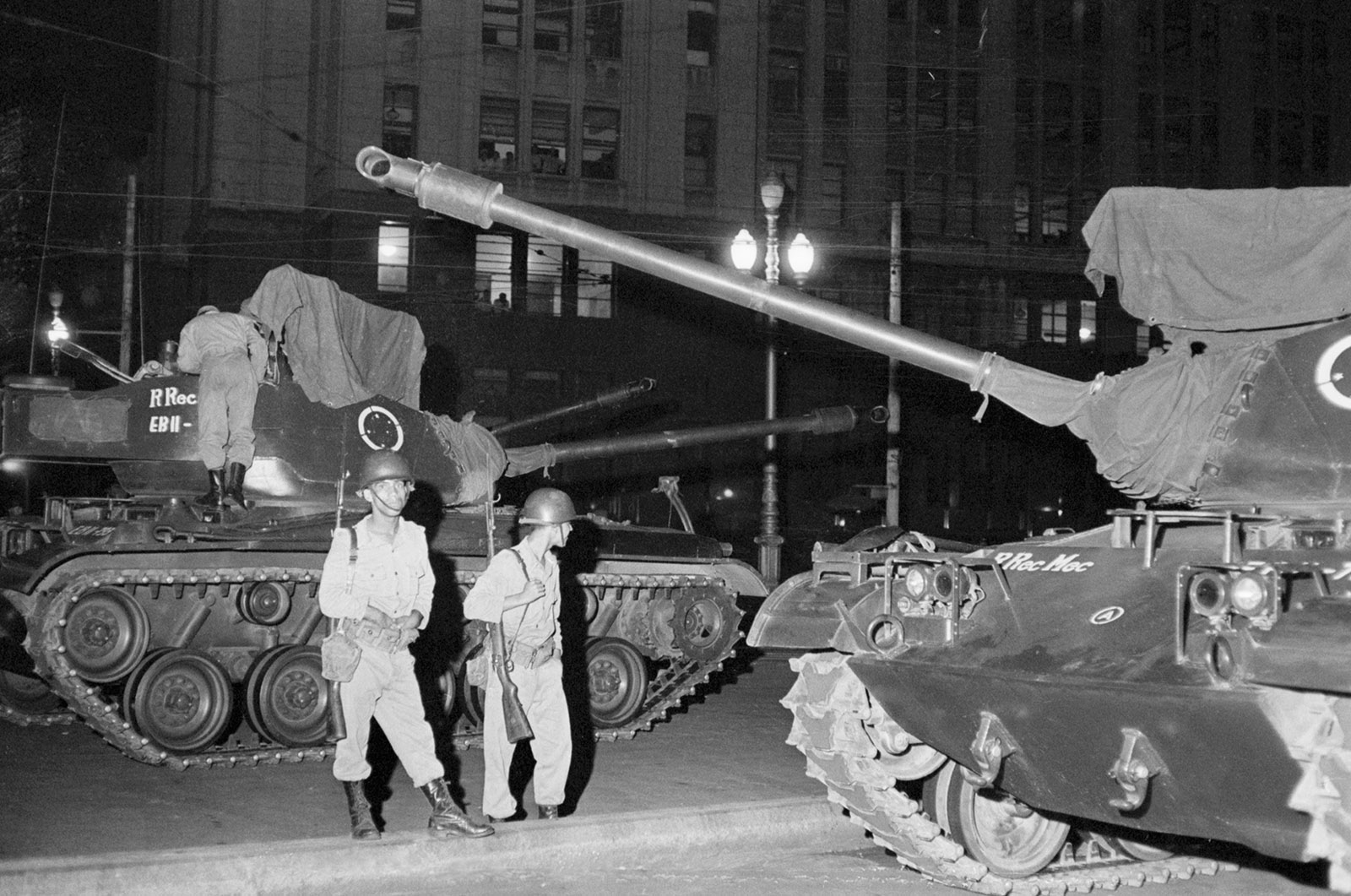

It was on March 31, 1964, that a group of poorly equipped members of the Brazilian Armed Forces began marching on Rio de Janeiro, where the elected president, João “Jango” Goulart, was in residence. A large conspiracy to remove him had already formed, but the action was not supposed to start that day. Outraged by what he saw as Goulart’s communism and subversion, General Olímpio Mourão Filho jumped the gun and made his way toward the Atlantic coast. Goulart flew to Brasília, the capital, but when it became clear to him that the military high command was now intent on his removal, he fled and then, under threat of arrest, went into exile in Uruguay. Tanks were parked outside Congress, and invoking an “Institutional Act” with no legal basis whatsoever, the junta declared that the left-wing members of the Congresso Nacional had lost all their legal rights.

These are the events and images often recalled when we talk about what is called, correctly, Brazil’s “military coup,” or “golpe militar.” Often forgotten, though, is that a huge part of Brazil’s political and economic elite supported the golpe at the time. Even before the First Institutional Act, the Congress declared the presidency “vacant” while Goulart was still in the country, in clear violation of the Constitution. Then, after forty of their colleagues had been expelled by the putschists, 361 of the remaining representatives voted to install Marshall Humberto de Alencar Castelo Branco—who had been plotting with generals, the United States, and some politicians to remove a legitimate president—as leader of the country. The US ambassador in Rio was certain that Brazil could become “the China of the 1960s” (in other words, turn communist), and wanted Jango out. All the major Brazilian newspapers except one supported the coup. Hundreds of thousands of mostly well-heeled Brazilians, suffering from an economic recession and believing Goulart was too left-wing, had already made known their preference for his removal in a series of marches “of the Family with God for Liberty.” Many of them believed rumors, intentionally spread by conservatives, that it was actually the president who was planning his own, communist coup d’état.

As part of Operation Brother Sam, Washington secretly made tankers, ammunition, and aircraft carriers available to the coup-plotters. None of that was needed. Some historians believe that one reason why Jango didn’t mount any defense is that he believed, like much of the rest of the political establishment, that the military would soon call elections as scheduled. It’s not clear that the Brazilian people actually supported the coup, and it is possible that Goulart would have been elected again, even allowing that, at the time, the majority of the population, including many descended from slaves and living in crushing rural poverty, were excluded from voting by literacy requirements. But almost everyone who truly mattered to Brazil’s political system was on board with Jango’s ouster, which is why these early days are often referred to as a “civil-military” dictatorship. The elites expected a relatively quick return to normalcy, as they saw it.

The problem with authoritarian regimes, however, is that they tend not to do what is asked of them and then just step aside. The “civil-military” dictatorship soon became simply a military dictatorship, one that tortured and killed thousands of dissidents.

Apologists for Brazil’s military regime plead that state murders numbered “only” in the hundreds, but those numbers refer to documented urban cases and ignore entirely the thousands of indigenous people who were reportedly slaughtered as the military regime rushed to develop the Amazon. And they forget the huge part that Latin America’s largest country played in shaping the region. In 1971—the same year that Bolsonaro entered the Armed Forces—Brazil supported a military coup in Bolivia. Later that year, it prevented a left-wing coalition from winning elections in Uruguay by moving troops to the border and threatening invasion. With encouragement from Washington, Brazil’s military rulers also worked to undermine the Allende government in Chile. When a CIA-backed coup installed General Pinochet in 1973, Brazilian intelligence officials were in Chile’s national football stadium, helping to turn it into a center for the detention, torture, and murder of the political opposition.

Advertisement

“The Brazilian dictatorship’s body count is relatively low when compared to Chile or Argentina, but it was abroad that it had the most devastating impact,” wrote Tanya Harmer, a historian at the London School of Economics, in a 2012 journal article. “Both through its example, its interference in other countries, and its support for counter-revolutionary coups.” Most notably, Brazil’s military dictatorship helped devise the infamous Operation Condor, an international network of terror and extermination across South America. Born of a fanatical anti-communism, the regimes under Condor murdered political opponents by the tens of thousands.

So when, in 2016, President Dilma Rousseff was impeached—in a process that may have been legal, but badly dented the legitimacy of the government—some began to talk about this history again. Mostly, it was those on the left, opposed to the new right-wing government of Michel Temer, who saw parallels between 1964 and the process by which largely corrupt lawmakers voted to oust a left-leaning president for a technical violation of budget rules. But it was Bolsonaro’s political ascent this year that has forced the whole country to look back on its past.

Bolsonaro’s ideology is best understood as Operation Condor plus the Internet. Recent international reporting has compared him to Donald Trump or seized on his contempt for identity politics, pointing out his record of sexist, racist, and homophobic statements, but these characterizations are insufficient. What Bolsonaro offers is an explicit return to the values that underpinned Brazil’s brutal dictatorship. Bolsonaro did not need to be “red-pilled” to believe that political correctness had gone too far in today’s Brazil; he has been consistent in his views for a long time. In 1999, just eight years after full democracy returned to Brazil, he went on TV to say the following:

Voting won’t change anything in this country. Nothing! Things will only change, unfortunately, after starting a civil war here, and doing the work the dictatorship didn’t do. Killing some 30,000 people, and starting with FHC [referring to then-President Fernando Henrique Cardoso of the Brazilian Social-Democratic Party]. If some innocents die, that’s just fine.

Besides defending the military regime more virulently than most of its actual leaders ever did, he built his political career on attacking human rights and LGBT people, repeatedly saying things like “the minority has to shut up, and bow to the majority.”

I spoke to Bolsonaro in 2016 before he voted to impeach Rousseff. He said the world would celebrate her removal, since he would be helping to stop Brazil from becoming North Korea. Later that day, when he dedicated his impeachment vote to the man who had overseen the torture of Rousseff in her days as a left-wing guerrilla, he became the public face of uncompromising opposition to the politicians who had run the country for over a decade (even though he often worked for them and benefited personally from the privileges bestowed on parliamentarians). And as more and more of Brazil’s political conversation has moved on to social networks, members of a new Brazilian alt-right have been able to spread misleading or outright false information about their preferred leader, Bolsonaro, and their hated left-wing enemies.

Over the next two years, as crime worsened and Brazilians watched Temer, an extremely unpopular president of very questionable legitimacy, roll back workers’ rights yet fail to restart the economy, support for the return of military rule shot up. And why not? If you were rich and stayed in line politically, things were never that bad—this kind of nostalgia was often reproduced in media and historical memory. Brazilian democracy has enjoyed only a few decades, and according to the folk memory of the dictatorship, there was far less of the corruption that many believe plagues Brazil today. One reason for the dictatorship’s unmerited reputation for clamping down on corruption is that it did clamp down on reports of corruption: in one case, when a diplomat announced he would publish a book about graft under the military government, the regime kidnapped, tortured, and murdered him.

“It’s really strange that so many people now believe that the military regime somehow delivered safety to Brazilians or managed the economy well, since, by the end of the 1970s, they were very often seen as corrupt and incompetent, and crime statistics were worsening due to the government’s own policies,” said Marcos Napolitano, a historian at the University of São Paulo and an expert on the dictatorship. His research has shown that by encouraging mass migration into urban slums with no public services, and allowing a militarized police to routinely use extra-judicial killings to control marginalized populations, the dictatorship actually set the country on the path toward its current widespread violence. The security services turned the logic of extermination they had used to eliminate the left opposition against the urban poor, and waged a low-level war that has never ended. Napolitano added:

Advertisement

It’s clear the way that Brazil transitioned into democracy has allowed for the return of politicians praising the military regime. There was no effective investigation into the crimes committed by the state, while instead there was a process and negotiation and reconciliation that allowed society at large to avoid a real discussion of what happened. And now there are some political elements that really remind us of the past. There’s a bitter middle-class resentment against the left, including parts of the left that aren’t even socialist.

Bolsonaro has never apologized for any of the incendiary positions he took over the decades. But he did moderate his tone slightly during this year’s campaign, after a late conversion to free-market economics that won him the support of international investors. Bolsonaro’s campaign slogan—“Brazil above all, God above everyone”—more or less explicitly recalled the patriotic, pro-family language of pre-1964 coup protests against Jango by hardline conservatives. By the time Brazilians voted last Sunday, some moderates were so fed up with the other options that they found ways to wave aside what Bolsonaro has actually said he wants to do.

“I voted for the PT [Workers’ Party] before, but we’re so tired of them,” said Bolsonaro supporter Carla Silva, a forty-five-year-old white acupuncturist at a voting center in an upper-middle-class neighborhood in São Paulo. When I asked if she considered him dangerous, she responded: “Oh, I am totally against his plan to give everyone guns, and what he has said in support of beating LGBT people. For the love of God, I’m against his rhetoric. But he won’t be governing alone, and he won’t be able to do everything he wants.”

Then there are those who appear to be fully behind Bolsonarismo. As Silva finished speaking, a young father and son walked out of the polling booth. The boy, maybe seven or eight years old, was carrying a giant toy rifle. In today’s Brazil, that is a clear family endorsement of Bolsonaro’s proposal to arm civilians and order police to shoot to kill criminals. Almost everyone I spoke to that day said they supported Bolsonaro. Some shouted it at me angrily and proudly, as if they knew that it was a transgressive thing to say, but they were going to do it anyway.

Support for Bolsonaro is highest among rich white Brazilians (especially rich white Brazilian men) and Evangelical Christians, but it’s impossible to win 49 million votes without backing from lots of regular people, too. On Sunday, carwash operator Julio Cesar Alves, thirty-seven, explained why he voted for Bolsonaro, even though he had happily voted twice for Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, Rousseff’s predecessor as leader of the Workers’ Party.

“I don’t think he will be great, necessarily, but he’s what we need right now,” said Alves, before explaining that he could barely pay his bills, and that his poor neighborhood has become more dangerous recently. “And I’m against the program to pay criminals in jail even more than I make.”

This is a myth, an example of the disinformation that is circulated and gains credence via social media. Most Brazilian prisoners live in appalling conditions. When I asked Alves where he heard about it, he responded, “Everyone knows, just check the Internet,” and pointed to my phone. Over the last few weeks, Brazilian social networks—especially the Facebook-owned WhatsApp messaging service—have been inundated with rumors and lies that clearly favored Bolsonaro. Most common are hysterical denunciations of the Brazilian left, which supposedly seeks totalitarian powers and supports criminality.

But the left was not the biggest loser in Sunday’s election. Former São Paulo Mayor Fernando Haddad, selected as a surrogate for Lula after the former president was imprisoned on corruption charges and banned from running again, managed 29 percent, and his center-left Workers’ Party will, just barely, remain the largest party in Brazil’s lower house. It was the parties in the center, which backed the impeachment of Rousseff, that were decimated—and largely supplanted by members of the previously tiny party that Bolsonaro chose as his election vehicle. If Rousseff hadn’t been removed, it’s easy to imagine that the center-right Social-Democratic Party (PSDB) would now be in a good position to win back power from the PT, said Flávia Biroli, a political scientist at the University of Brasília:

The PSDB made a gigantic tactical error supporting the impeachment, which has had consequences for the whole country. For decades, Bolsonaro had always been a bizarre figure from our past that never fit into Brazilian politics. But it was the present moment—the widespread anti-political sentiment, the death of the center, and a global environment that is more tolerant of these kinds of challenges to the status quo—that allowed him to take center stage.

Haddad, seen as a capable moderate within the PT, will face Bolsonaro in the run-off. He has a chance, but his opponent is the front-runner. And even if Haddad wins, the ideology that powered South American dictatorships is back. He would face a radical right in Congress and powerful factions among the population that would view him as illegitimate and likely spread misinformation to undermine him. In the days since Bolsonaro won the first round, he has refused to sign a pledge not to spread false information online. Instead, he claimed, without evidence, that he would have won already if the voting machines had worked properly; and he pledged to “put an end to all types of activism in Brazil.”

Some Brazilians fear, not precise parallels with the past, but frightening new scenarios. Perhaps the impeachment wasn’t actually a repeat of the 1964 ouster. Perhaps Rousseff’s removal was just the prologue, the first act, to be followed by a Bolsonaro win, and then consolidation of authoritarian rule: a digital-era dictatorship that does not need direct army intervention to suppress dissent and rule by fiat. Maybe Lula’s imprisonment, after a bitter court battle, made this all possible. Or perhaps Haddad will scrape by with a win but then falter, inspiring a more violent conservative reaction.

A few days after last weekend’s vote, I spoke to Ivo Herzog. In 1975, when Ivo was just a boy, his father, Vladimir Herzog, a left-wing journalist, was abducted, tortured, and killed by the dictatorship. The photo of Vladimir’s dead body shocked the country at the time. Ivo, who now works at an organization named for his father that promotes human rights and historical memory, the Instituto Herzog, has been involved in efforts to rally a broad front of opposition to Bolsonaro’s election campaign, but Ivo is not optimistic.

“I think we may be taking a huge step backwards. I’m very afraid,” he said. “The political situation puts me under intense stress. I can’t sleep without medication. But I’ve decided now is not the time to back down from the fight.”