Charlotte Anna Perkins was born squarely within the Victorian era, on July 3, 1860, in Hartford, Connecticut, twelve years after the first women’s rights convention, held in Seneca Falls, New York, and less than a year before the Civil War broke out. By the time Gilman died in 1935, she’d seen her country go to war, women achieve the vote, and the early years of the Great Depression. She’d also glimpsed more than a few of the material advances that would come to reshape the lives of women and families, among them the legalization of condoms, the invention of the zipper, and the sale of frozen foods.

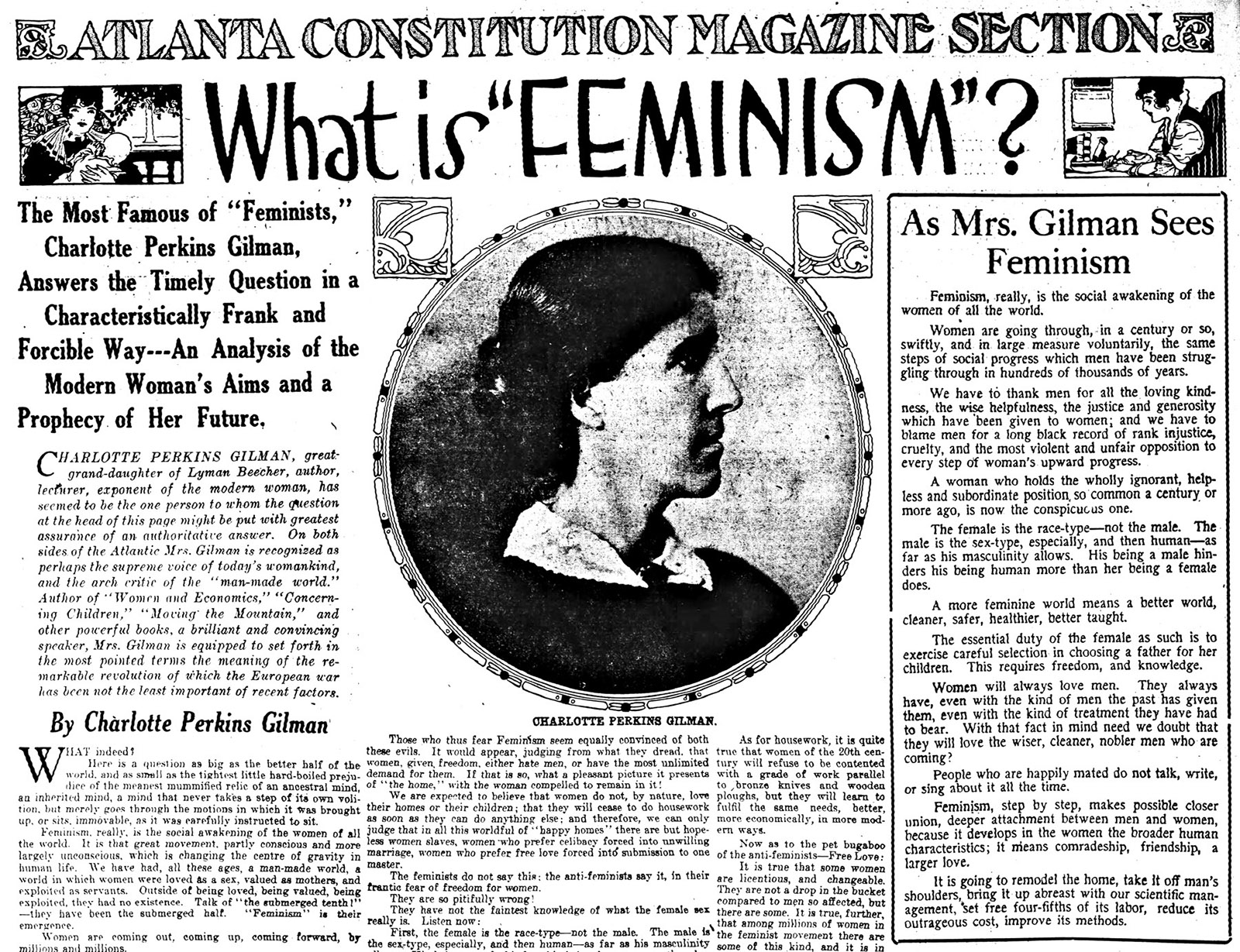

Gilman was never merely a witness to history’s unfolding. From an early age, she yearned to mold society to her vision, an impulse she inherited from her paternal line, the prominent nineteenth-century Beecher clan. Her great-grandfather, Lyman Beecher, and great-uncle, Henry Ward Beecher, were influential ministers. Her great-aunts included Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of the popular 1852 abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Catharine Beecher, an author and educator who promoted women’s higher education and founded her own school, and Isabella Beecher Hooker, a leader in the suffragist movement.

This lineage proved far more impressive than her father’s fitness for parenthood; he vanished when Gilman and her fourteen-months-older brother were still infants, leaving his wife to raise the children alone. Over the next eighteen years, the threesome moved nineteen times, living in boarding houses and the homes of various family members throughout New England. The familial generosity ceased in 1873, when Gilman’s mother finally filed for divorce, an extremely rare decision at the time, of which the Beechers did not approve.

This unstable upbringing had a profound influence on the eventual adult. Though by background and appearance a member of the white upper-middle class, Gilman enjoyed few of its attendant privileges, whether comforts like new clothing or the less tangible advantages of a formal education. (All told, she recorded four years among seven different elementary and secondary schools, leaving school when she was fifteen.)

During early adolescence, she fashioned herself as a stoic, consciously cultivating personal deprivations and choosing the bracing rewards of intellectual study and physical exercise over all—other than the joys of imagination: “I could make a world to suit me,” she recollected thinking in her autobiography. This creativity extended to the sartorial realm. She designed and sewed her own clothes, even her own special “species of brassière,” and at a time when tight, constricting corsets were a staple of women’s wardrobes, she refused to wear one. At seventeen, she confided to her diary that she would never marry, because doing so would thwart her plans to better humanity.

It isn’t difficult to see in this fiercely individualistic young woman the seeds of a radical. Possibly, the combination of her self-directed reading and lack of traditional schooling allowed for the habit of unconventional thinking that characterized her long career. Certainly, witnessing the travails of her visibly unhappy mother, forced to rely on the charity of extended family, impressed upon the girl the necessity of financial independence. In 1878, at age eighteen, she enrolled in classes at the Rhode Island School of Design and began earning money as a commercial artist.

In 1879, Gilman fell in love with a young woman her age, Martha Luther. It was her first significant romantic relationship, and she fervently hoped they would become life partners. Intense same-sex attachments were common among women during the nineteenth century, whether adolescent “romantic friendships,” in which two girls exchanged passionate endearments, or adult “Boston marriages,” in which two spinsters set up house without the economic support of a husband.

Eventually, though, Luther called off the relationship and announced her engagement to a man. Gilman was devastated. In her 1882 journal, she emphatically swore off “love and happiness” and re-committed herself to public service, declaring “work” would be her emotional salvation.

Ten days after writing that journal entry, however, Gilman met a charismatic young painter, Charles Walter Stetson. For two years she refused his repeated proposals, until finally breaking her anti-marriage vow. On May 2, 1884, she and Stetson were wed in a small ceremony in Providence, Rhode Island.

Less than a year after the wedding, Gilman gave birth to their daughter, Katharine, and then succumbed to a postpartum depression, lasting nearly three years, that became the genesis of her most famous work. In the spring of 1887, desperate for help, she traveled to Philadelphia to undergo the now-infamous “rest cure” with Dr. Silas Weir Mitchell, the era’s venerated nerve specialist (Edith Wharton was also a patient). His treatment: “Live as domestic a life as possible,” and “never touch pen, brush, or pencil again as long as I lived,” Gilman later wrote in an essay. She tried to do as he prescribed—and then suffered a nervous breakdown.

Advertisement

Yet, before long, she found the strength to reject her doctor’s orders and make her own diagnosis. The emotional confines of marriage and motherhood were smothering her, she decided, and she would pursue her own course of treatment, what she cheekily called her “west cure.” In the summer of 1888, she persuaded Stetson to agree to a separation, then moved with Katharine across the country to Pasadena, California, where, after a bumpy start, she finally embarked on her ambition to become a “world-server” and began writing and publishing in earnest.

*

In literary terms, Gilman was never a masterful writer. Unlike her contemporary Wharton, who created some of America’s greatest fictional heroines, Gilman wasn’t interested in, or perhaps capable of, orchestrating a wide cast of characters with complex inner lives, or perfecting a prose style. Even so, what she brought to the page retains a distinctive place in American letters: a captivating mix of perspicacity, subversiveness, and humor, propelled by an admirable taste for experimentation and an inexhaustible work ethic.

The Yellow Wall-Paper is rightly regarded as Gilman’s best fictional work. She wrote it in a two-day white heat during the summer of 1890, but it didn’t appear in The New England Magazine until January 1892. (Her rejection letter from The Atlantic read, “Dear Madam, I could not forgive myself if I made others as miserable as I have made myself.”) A chronicle of one woman’s descent into madness, the story is commonly interpreted as a feminist critique of Victorian America’s patriarchal medical system. But it is also a notable example of Gothic fiction, recalling the unreliable narrator of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart,” published a half century before, and anticipating Shirley Jackson’s psychological suspense stories a half-century later.

The plot begins straightforwardly. A never-named narrator and her physician husband, John, have retired for the summer with their newborn to a long-abandoned country house, so she may rest. The narrator is suffering from what her husband dismisses as a “temporary nervous depression—a slight hysterical tendency.” Forbidden to work, she is confined to a nursery at the top of the house, a spacious room with windows on all sides and a “repellant” yellow wallpaper stripped off in giant patches. “I never saw a worse paper in my life. One of those sprawling flamboyant patterns committing every artistic sin,” the narrator confides in the secret diary that comprises the story. More ominous: “There is a recurrent spot where the pattern lolls like a broken neck.”

Soon, she detects the figure of a woman trapped inside the paper, “creeping” behind the pattern, with whom she eventually merges completely. The ending is left hauntingly unresolved: When John faints after discovering his wife crawling around the perimeter of the room, is the narrator triumphant? Or does the fact that she continues to “creep over” his body mean she’s now trapped in a never-ending cycle?

*

In December 1892, Gilman’s husband filed for divorce. Two years later, when the divorce was finalized, Gilman relinquished full custody of her daughter to Stetson, garnering even more public disapprobation. She mined this turmoil for “The Unnatural Mother,” drafted in 1893 and first published in an 1895 issue of The Impress, a literary weekly put out by the Pacific Coast Women’s Press Association, of which she was the editor at the time. About a young mother who warns the townspeople of a coming flood instead of tending to the safety of her baby, the story plays on popular conceptions of maternal feeling; the mother saves the town, dying in the process, but is posthumously castigated anyhow for risking her child, who survives. (Intriguingly, the mother’s name, Esther Greenwood, is also that of the heroine of Sylvia Plath’s 1963 autobiographical novel The Bell Jar. It is entirely possible that Plath read Gilman, though scholars haven’t determined if the reference was intentional.)

Once she’d found her stride, Gilman was unstoppable. In 1893, she published her first poetry collection, In This Our World, to warm reviews. Around this time, she decided her primary concern to be the “woman question,” particularly suffrage and economic independence. She also became involved in the so-called Nationalist movement, a short-lived nineteenth-century network of socialist groups committed to nationalizing private property (the name bears no relation to our contemporary understanding of nationalism). Inspired by Edward Bellamy’s 1888 hugely successful utopian science fiction novel, Looking Backward: 2000–1887, the movement’s central principles—most notably, a belief in progress and an emphasis on communal values—made a deep mark on Gilman. She incorporated ideas about cooperative living into her feminism and spent the years between 1895 and 1900 constantly traveling as a public speaker, a woman “at large,” as she liked to put it.

Advertisement

In 1898, she published her first important nonfiction book, Women and Economics, which argued for the necessity of female economic independence to the improvement of marriage and the family. Foreseeing our current debate over “work-life balance,” she advocated for professionalizing housework and for building communal living spaces with public kitchens so that women wouldn’t be permanently stuck alone cooking and cleaning. The book catapulted Gilman into a yet higher sphere of influence and crowned her the leading intellectual of the women’s movement.

The turn of the century brought a new chapter in Gilman’s life. In 1900, she married her first cousin, George Houghton Gilman, a Wall Street attorney, and settled down with him in New York City. Over the next several years, she published three more nonfiction books: Concerning Children (1900), The Home: Its Work and Influence (1903), and Human Work (1904). Along with contributing articles to a wide range of mass-market magazines and newspapers, as well as academic journals, in 1909 Gilman inaugurated her most ambitious endeavor to date: her own monthly publication, The Forerunner.

For more than seven years, she wrote, edited, designed, typeset, and produced every inch of eighty-six issues, each twenty-eight pages long and going out to 1,500 subscribers. Free to unleash her voice whenever and however she wanted, without having to constantly navigate the complicated strictures of the publishing marketplace, she let loose in an inspired torrent of “stories short and serial, article and essay; drama, verse, satire and sermon; dialogue, fable and fantasy, comment and review,” as she described in her statement of purpose. The cover image, her own pen-and-ink illustration, perfectly captures her politics: an infant of genderless appearance stands atop a globe flanked by a couple—the woman supports the child with her left arm, the man supports the woman with his right arm, and with their free hands, they hold the globe between them, that is, the fate of the family and of the world at large.

It was in these pages that she first published, over the course of 1915, what is, besides The Yellow Wall-Paper, her most significant work, the satirical, utopian science-fiction novel Herland. While most science fiction takes place in the future, Herland is about an all-female society set in Gilman’s present day. Two thousand years before the story takes place, a volcanic eruption blocked off the country’s only point of egress, killing most of the men in the process; those who remained, murderous slaves attempting to violently seize power, were obliterated by an uprising of women. Eventually, the survivors, all female, discovered that via parthenogenesis (asexual reproduction) they could get pregnant and give birth to five girls apiece, who were also parthenogenetic.

In this way, Herland had created and maintained a thriving population over the millennia. When they’d reached the risk of overpopulation, they instituted the practice of choosing biological motherhood; that is, a woman could decide for herself if she’d give birth to a child or instead channel her generative energies into designing a new building, for instance, or writing a novel.

The story begins when three American men on a scientific expedition—Terry, a male chauvinist playboy; Jeff, a sentimental doctor; and Vandyck, a sociologist and the feminist-minded narrator—stumble upon this mythical place they’d never believed to be real. The book’s comedy turns on the ways in which their sexist presumptions—many, sadly, still recognizable today—are toppled. Far from the “sublimated summer resort—just Girls and Girls and Girls” that Terry had imagined Herland to be, they discover instead an ideal society that is communal, co-operative, and peaceful. Herlanders maintain a simple vegetarian diet and exercise daily. Their clothes are uncomplicated, airy, and comfortable; there isn’t a corset, or even a special brassière, to be found. The means of production are entirely self-sustaining. Laws are revised every twenty years.

There is a snake in this garden, however—not in the plot, but in Gilman’s conception of this utopia-in-her-time: a desire for racial purity. For all her progressiveness when it came to equality for the sexes, Gilman was a xenophobe, a regrettably common response at the turn of the last century to the waves of immigrants resettling in urban areas. This prejudice dovetailed with her simultaneous embrace of eugenics, then a respectable academic field and a widespread enthusiasm even among, or especially among, social reformers. Between her passion for science and sociology and her constitutional faith in the forward march of progress, Gilman was quick to adopt the idea that some human populations are genetically superior to others, and that by playing to the strengths inherent to each race, poverty could be eradicated and society vastly improved.

Moreover, at a time when sex education and effective birth control weren’t widely available, Gilman saw in eugenics an answer to the scourges of sexually transmitted diseases (a major public-health issue until penicillin was found to treat syphilis in 1943) and involuntary motherhood. Feminists and activists in general were divided over eugenics: Margaret Sanger, Emma Goldman, and Olive Schreiner all shared Gilman’s views, while Jane Addams, Lillian Wald, and Florence Kelley fought against them.

Viewed one way, the practice in Herland of women’s consciously deciding whether or not to give birth is a refreshing rejoinder to the age-old expectation that all women must become mothers. Viewed another way, it appears perilously similar to the then-widespread use of involuntary eugenic sterilization as a means for controlling “undesirable” populations. Now considered a gross abuse of human rights, during the twentieth century eugenic sterilization was practiced in thirty states, starting in 1907 and lasting into the 1970s. Although the practice of sterilization does not appear in Herland, and there is no evidence that Gilman advocated for the practice in real life, it cannot be overlooked that she believed native-born white people to be genetically superior to other groups.

By the 1930s, eugenic feminism was on the wane; Gilman’s “race awareness,” as she called it, did not win her many new followers, and she came to be regarded as far less relevant than she once had been. By the time she died, in 1935, all her books were out of print, and early posthumous efforts to keep her reputation alive foundered. It was not until the 1970s, amid the renewed interest of second-wave feminists, that scholars rediscovered this forgotten writer. Yet their initial rush of excitement in doing so was often replaced, as her writings on race came to light, with a sense of confusion and disappointment. How could it be that this progressive feminist activist followed such an injurious line of thinking?

And yet, so much of what Gilman fought for has reverberated over the decades. Her vision of a companionate marriage founded on economic equality between the sexes, and the need to free women from the burdens of housework, anticipated many of the issues later taken up by modern feminism, from American women’s fights in the 1960s for equal employment and pay to Italy’s 1972 Wages for Housework campaign. Likewise, her conviction that gender identity is fluid and not fixed foreshadowed third-wave feminists’ concept of a continuum of gender. The Forerunner might even be seen as a precursor to the “riot grrrl” practice of self-publishing zines. Even our most contemporary concerns with the sexual predation of women in the workplace can be traced back to Gilman’s idea that revolutionizing marriage would free wives from the conjugal obligation to serve their husbands’ erotic needs—“sex slavery,” as she called it.

Even Gilman’s manner of death evinced her progressivism, presaging today’s right-to-die movement. On August 17, 1935, three years after being diagnosed with incurable breast cancer, she “chose chloroform over cancer,” as she wrote in her suicide note, before deliberately overdosing herself. At that time against the law throughout the US, euthanasia is today legal in a handful of states. In death, as in life, Gilman chose to make her own rules.

This essay is adapted from the author’s introduction to The Yellow Wall-Paper, Herland, and Selected Writings, by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, in a new edition published by Penguin Classics.