We are all foodies now, aren’t we? We want to know where our food comes from; whether any sentient beings killed to provide our daily fare have led the best lives possible; and if our vegetables have been grown without using anything that could be bad for us. We want to know who farmed them, and how, and that the farmer can make a decent living. And we wish to be assured, not only of the quality of our food, but also of its safety, security, and sustainability.

So, naturally, you’d expect an exhibition titled “Food: Bigger than the Plate” to trade on the universal Foodism of the educated, enthusiastic people who might attend it. For example, say the co-curators Catherine Flood and May Rosenthal Sloan in their catalog introduction to the section on “Trading”:

The issue of how our food gets to us does not tend to be replete with sexy or even palatable stories. Where celebratory narratives around the trade of food do exist, they often treat provenance as a feel-good factor. This runs the risk of unhealthily fetishizing so-called “foodie” culture by celebrating too fervently buying choices that are simply out of reach for most of us.

As the co-coiner of the “f”-word, when the late Ann Barr and I published The Official Foodie Handbook in 1984, I have to dissent. Though we were poking gentle fun at what we had noticed and anatomized thirty-five years ago, foodie culture is now less about flaunting how much you paid for your chicken, and more to do with caring about the welfare of poultry raised for food. That is why Europeans, including (for now) Britons, are so horrified and disgusted by the threat of “chlorinated chicken” imported from the US. It is not a question of harming the consumer; it is about why, if the chicken has lived in decent conditions, it should be necessary to treat its carcass with chemicals? Being a foodie today entails not consumer fetishism, in fact, but precisely ethical considerations about our diet—albeit, yes, from a certain position of privilege and comfortable choice.

You get a shock when this exhibition, ostensibly devoted to food, begins with the topic of excrement. But there is a logic to this. While it is not, perhaps, the first thing we like to think of when the topic of food is on the table, waste in every sense is a vast and genuine moral problem. This is especially true in those parts of our planet where the population must contend with chronic shortages of calories, while the rest of us, from retailers to individual eaters, throw out unthinkably large quantities of perfectly edible, nutritious food every day. The reverse pathway of the exhibition’s rooms, from excreting to eating, is thus anything but frivolous; it is explained by this quotation froma Dutch design student in the co-curators’ essay: “I imagined the current design world as an organism. What does it eat? What does it excrete? Well, I see it shitting chairs…” The student, Mathilde Nakken, “subverted the classic project of the industrial designer by baking 100 iconic chair designs in bread.” Her 2015 manifesto project was titled “Make Food, Not Chairs.”

Disappointingly to me, then, this V&A exhibition is less about food than conceptual art and design. These terms, together with subversion, are very much its watchwords. Hence the almost amateurish—or deliberately improvisational—appearance of this good-sized show at Britain’s premier design and crafts museum, with hundreds of stacked plastic crates and flimsy wood-fencing delineating sections. Even the catalog’s typewriter-like font matches this low-rent look.

The organization of “Food” proceeds from composting (including the commercial use of night soil and urine) and farming, to trading and cooking. Only in the final section, eating, do we get a few curious recipes—but even this is in keeping with the mission to realize “a more just, biodiverse, and beautiful food system,” rather than being about what we put in our mouths.

The section “From the ‘smart kitchen’ to ‘kitchenism’” pays lip-service to the Frankfurt kitchen of 1926, the modernist architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky’s first-ever fitted kitchen. This includes two metal scoops said by the caption to be kitchen drawers, but it took a good deal of imagination and careful study of the catalog photo of the Frankfurt kitchen to work out how these scoops fit into the scheme with the conventional rectangular solid wooden drawers alongside.

“Kitchenism” turns out to be a term invented by the architect Charles Jencks, famous for his better-known coinage, “Post-Modernism.” The word refers to his idea of the kitchen as the central social hub of his designs for a chain of cancer-care centers in the UK. Kitchenism replaces the traditional vestibule for a reception area, Jencks explains, because “The centrality of food and drink allows people to enter and exit without declaring themselves, try things out, listen or leave without being noticed. You can insinuate yourself in the kitchen on any number of pretexts.”

Advertisement

The show is indeed very keen on “subversion.” The curators find it in everything from reusable coffee cups made from used coffee grounds to a film by “Honey & Bunny,” the conceptual artists Sonja Stummerer and Martin Hablesreiter. A video playing in the final room shows them dressed alike and sitting at a conventionally laid table. From whole cucumbers set before them, they peel strips. Instead of eating any, with perfect comic timing they each place a strip over one eye, from their foreheads to their cheeks. The film is truly an injunction to play with your food—an invitation that the curators’ leaden prose makes sound a lot less fun: “When we upend our ideas of what is proper around the table and start to explore the bigger picture of what is on our plate, the power of eating as a means of celebration, subversion and citizenship comes into focus.”

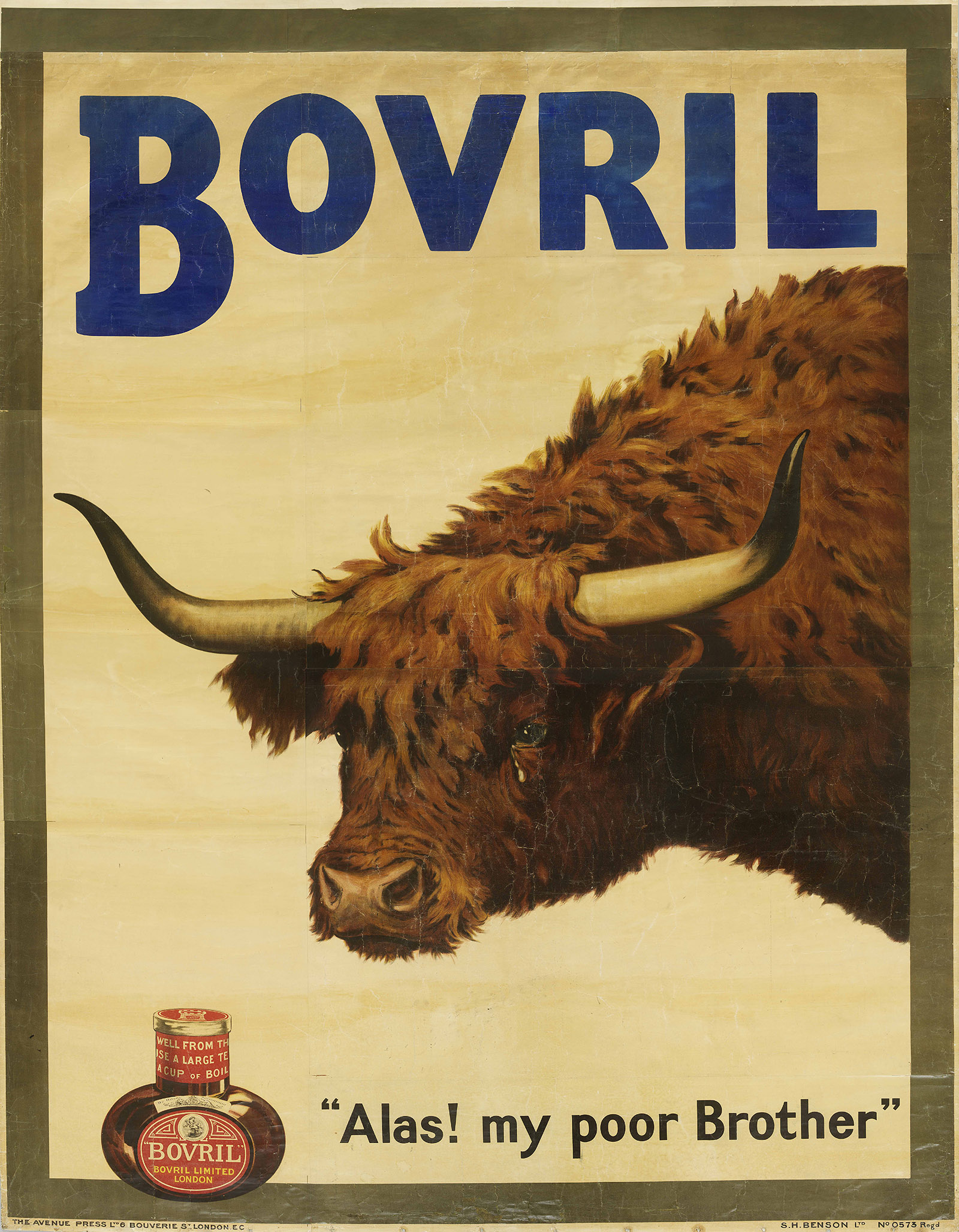

That reflects a weakness of a show dominated by captions rather than images. One striking exception to this rule is the 1905 advertising poster for the beef concentrate Bovril that shows an enormous shaggy-coated, longhorn steer peering at the tiny jar of Bovril in the left-hand corner, with a tear dropping from his eye: “Alas! my poor Brother.” No beef tea was on offer, but it is with relief that I can report there is some actual, edible food in the exhibition.

The Loci Food Lab, a traveling food stand run by the Center for Genomic Gastronomy (“an artist-led think tank that examines the biotechnologies and biodiversity of human food systems”), presents a tablet that tells you how to compose “a personalized, bioregional” snack from a wooded area of Britain. From a list of desirable virtues of “a great food system,” you can choose three items to sample. The base of my tiny canapé, assembled with tweezers, was a cracker made from “Essex chia seeds, British yellow peas & quinoa from Home Farm Nacton.” On this was “wild spread: foraged English mushrooms & wild herbs,” plus “revitalized relish: tomatoes too ugly for local restaurants & supermarkets,” topped by “pop heritage: crisped Essex barley & Somerset spelt,” and wee blobs of “sheep shaped landscape: Seven Sisters cheese made in Haywards Heath, Sussex.” It was arrestingly crunchy and savory.

To be sure, the Comté cheese made using microbes taken, we’re told in the label, from chef Heston Blumenthal’s pubic hair is as playful as it is subversive. But there is much that is challenging—from intellectually stimulating to simply difficult, even repellent—in this exhibition, such as the recent use in agriculture of endophytes, newly discovered micro-organisms that live inside plants. But it is amusing to learn that there’s an Endophyte Supper Club “where biological hobbyists meet to identify, discuss and taste” them. Some of these will no doubt lead to the development of biopesticides or biofertilizers. But the theme of this scatter-shot show remains elusive: Is it about food really, or is it a show of food-related conceptual art?

The V&A could usefully have taken a leaf out of its own history. In the catalog foreword by the museum’s director, the historian and former Labour Party parliamentarian Tristram Hunt, we learn that the V&A boasted the world’s first “purpose-built museum refreshment rooms,” designed by William Morris’s firm. The V&A also included, Hunt goes on, “an early food museum, alongside displays of working fish hatcheries—installed by the eccentric, visionary zoologist Frank Buckland.”

As it happens, I belong to a Birmingham-based dining society that bears Buckland’s name and celebrates his bizarre ambition to eat one member of every living species. But this long-ago pioneer of zoöphagy (1826–1880) was also a forerunner of what we would recognize today as a true foodie, one who thought long and hard about food-security issues and alternative agricultural modes. He urged mankind to eat new, sustainable sources of protein, especially insects, and to care for the environment for the sake of all the planet’s creatures, including the non-edible ones. Buckland’s ideas about food would have been something the curators might fruitfully have pondered when planning this show. Educational it is, but you’re never entirely clear whether you’ve wandered into a biology class or a design studio.

Advertisement

“Food: Bigger than the Plate” is at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, through October 20.