San Juan, Puerto Rico—Of all the things I did not expect to see on the barricades outside San Juan’s Justice Department after midnight, it was a boy blowing a shofar at the cops. Noel, as the polite, tousle-haired, tefillin-wearing kid introduced himself, was a University of Puerto Rico student who had been spending nearly every waking hour on the streets since the first days of the protests that eventually toppled Governor Ricardo Rosselló. They had been the most beautiful days of his life, he said. Once, he had yearned to leave Puerto Rico and its paltry job prospects. Now, there was nowhere else he’d rather be. He raised the shofar.

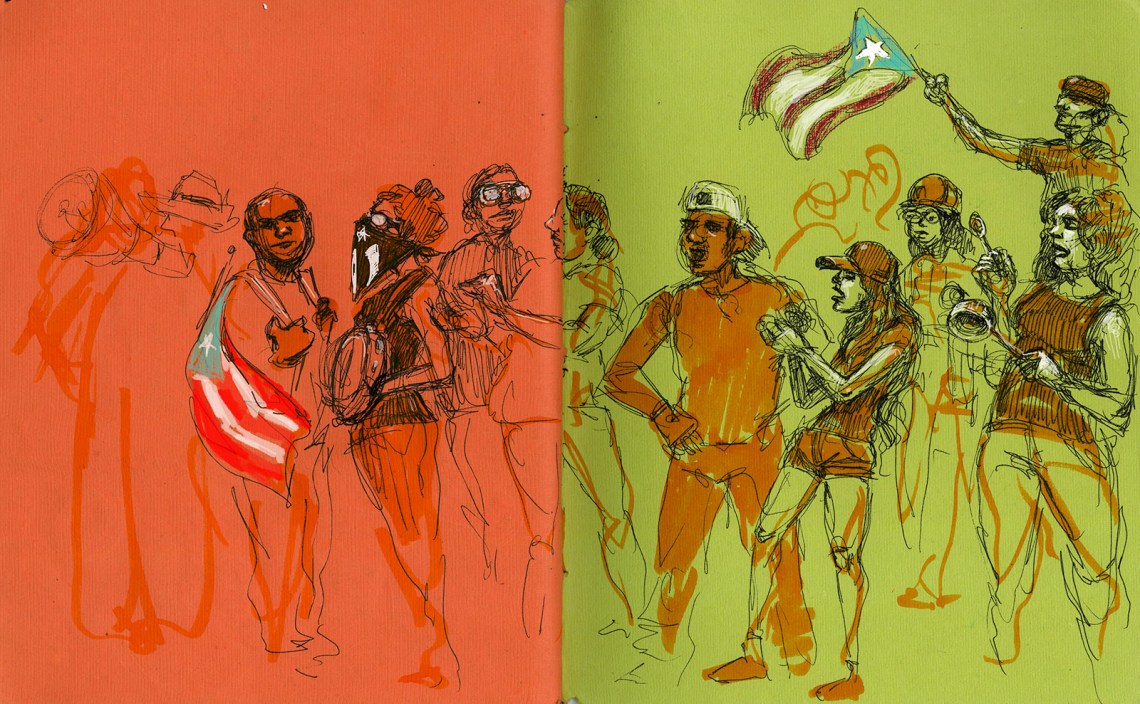

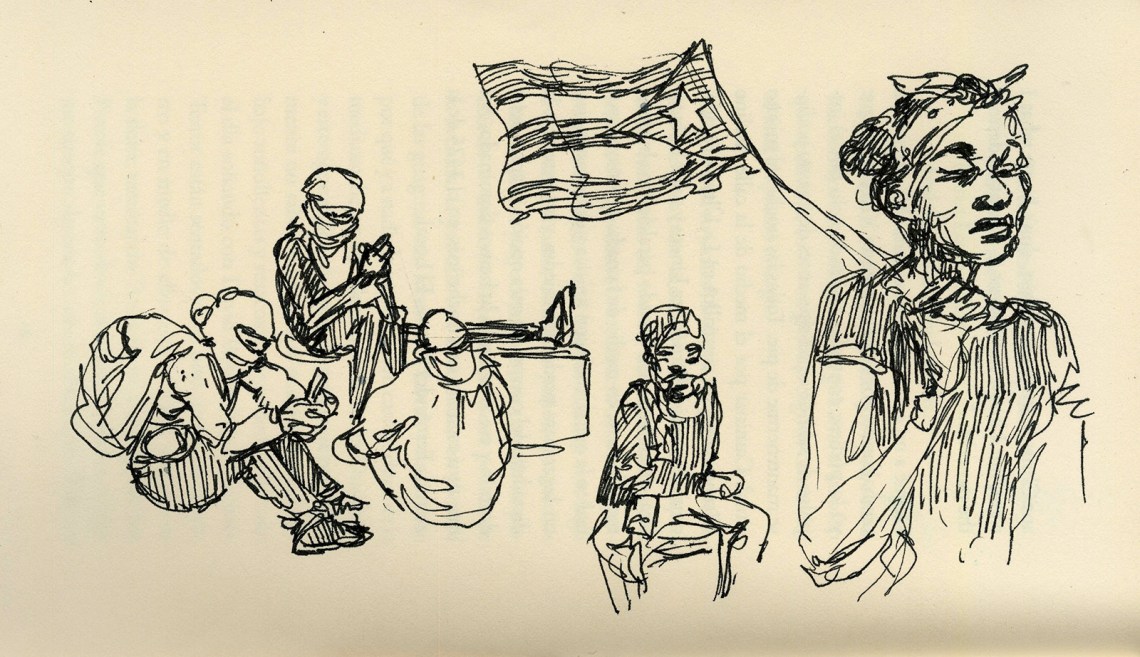

“This isn’t just for the synagogue. It’s for moments of history,” he told me. A few minutes later, fifty or so protesters hopped the concrete fence that separated us from the highway. The cars halted before them. The protesters were young, exquisite, and mostly masked. They waved Puerto Rican flags, banged on pots, shook the outstretched hands of supportive motorists, then jumped up and down, bathed in the headlights, ecstatic in their own bodies.

I arrived in San Juan on July 26, two days after Rosselló had announced his resignation, and everyone seemed convinced that a new Puerto Rico was being born. “I had nearly given up,” said José, a restaurant manager whose design studio went bankrupt after Hurricane Maria. “The citizens of a colony are now teaching the citizens of the empire what people power can do,” wrote my friend Christine Nieves, an organizer on the island’s eastern end. Sugeily Rodríguez Lebrón, a performer with the radical artistic collective AgitArte, told me she had waited for this moment her entire life.

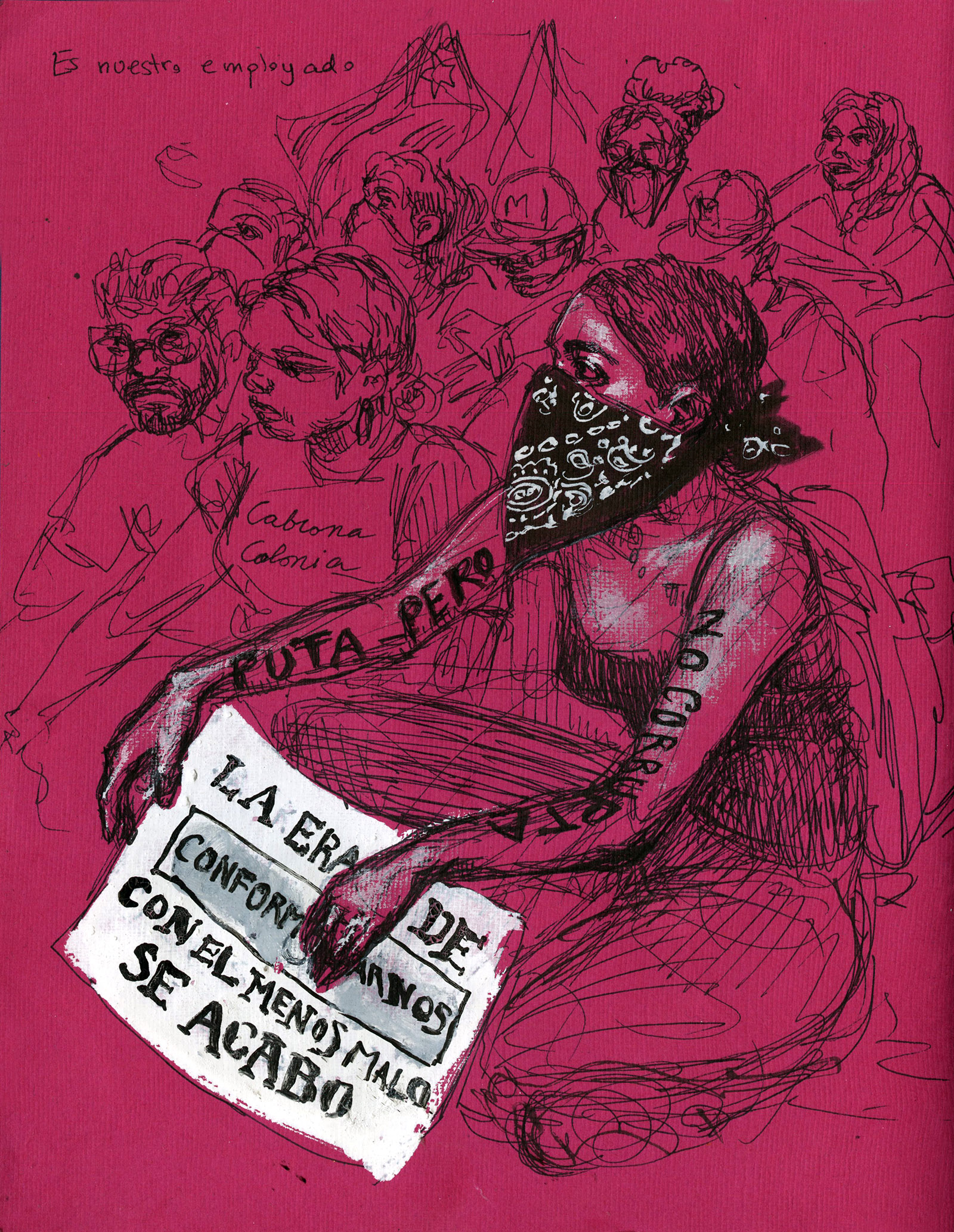

The protesters had done more than boot Rosselló from office. They wanted the head of every politician that had cheated and mocked the island, whether or not they had taken part in the recently leaked texts and chat messages between the governor and senior officials. “Clean the house,” the slogan went, and by the day, protesters improvised new chants savaging each potential Rosselló heir apparent. Protesters repudiated Puerto Rico’s two-party system as a corrupt Punch-and-Judy show in which each side took turns to build their patronage networks and made empty promises of either statehood or greater autonomy; and they rejected, too, the neocolonial Fiscal Control Board imposed by Congress in Washington, D.C., that has been wrecking the island’s economy with austerity measures in order to service unpayable, possibly illegal debts.

The protests had revealed, in the words of Puerto Rican writer Ana Teresa Toro, “the true social animal that we are: a beast that is joyous, wild, indocile and untamed, that has slept… until now.” Protesters renamed the streets around La Fortaleza “Calle de la Resistencia” and “Calle de la Revolución.” The barricades in front were transformed into stages for selfie posts. One person after another clambered up, grinned, and waved their pale-blue independence flags.

To understand how we got here, we have to look back to Hurricane Maria in 2017. According to a Harvard study, more than 4,000 Puerto Ricans died in Maria’s wake, mostly the old and the poor. They were killed not just by the storm, but by the months of neglect afterward, by exhaustion, infections, injuries, by lack of electricity, by the heat and lack of meds, by the leptospirosis in the water, by heartbreak at losing their world. Many of their bodies were left to rot in trailers, then cremated hurriedly without autopsies, so that Governor Rosselló could present an artificially low death count. His wife hastily constructed a charity, Unidos por Puerto Rico, that hoarded desperately-needed aid in the San Juan convention center. At the time, Puerto Ricans told me it was so she could use the donations as a backdrop for photo-ops; the FBI is now investigating the organization’s finances. In the leaked chats, his buddy joked about feeding Maria’s dead to vultures.

Realizing that they had been abandoned by both the local and federal governments, Puerto Ricans turned to their neighbors and to the diaspora, creating an island-wide network of mutual aid centers that exists to this day—learning about their own strength, solidarity, and resilience in the process. More darkly, post-Maria trauma also led to an upsurge of domestic violence. Last November, the feminist group La Colectiva Feminista en Construcción camped outside Rosselló’s mansion to demand that he declare a state of emergency over the epidemic of violence against women. Police expelled the women with pepper spray and batons. On July 11, La Colectiva Feminista called the first of the protests that brought down Rosselló.

Advertisement

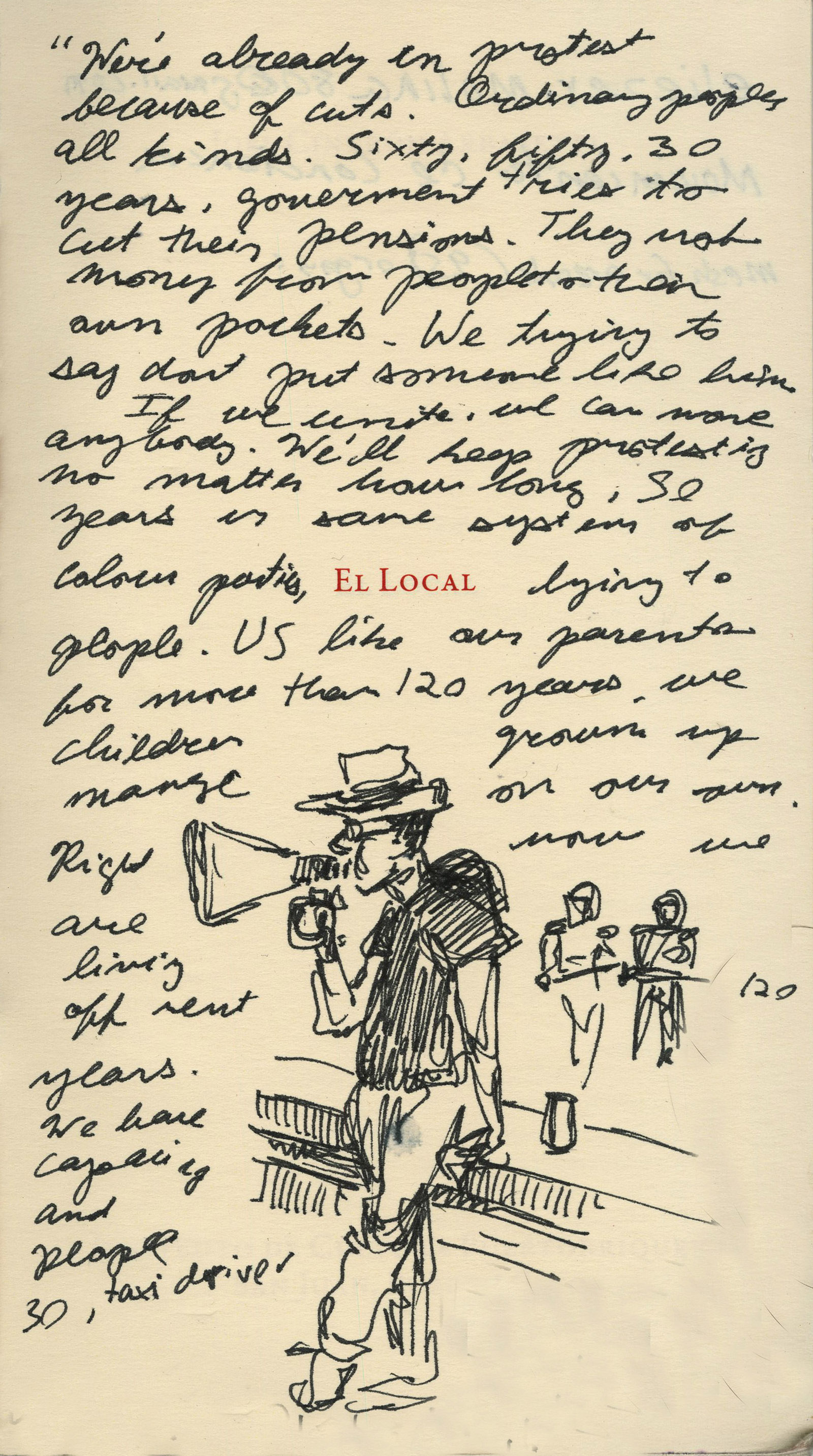

But the roots of the protest movement are deeper still. They go back to other, older struggles, including the 2010 student strike at the University of Puerto Rico, a sixty-two-day-long, bitterly fought battle against budget cuts that saw the emergence of the asambleas, public assemblies that Puerto Ricans are now using in cities across the island to break through isolation and hash out what should come next. Along with two hundred other people, I sat at one such asamblea in Caguas, a city about twenty miles south of San Juan. Held outside City Hall, with the building’s awning acting as shelter against the pouring rain, the meeting was led by Giovanni Roberto, a former student leader who came out of those strikes and then founded the first mutual aid center in Caguas that helped his neighbors survive Maria. A quiet man with dreadlocks, perpetually dressed in black, Roberto ran through their democratic process—of breaking into groups, designating a speaker, and each group presenting a priority. I saw every type of person, from Antifa punks to tiny abuelas, debating how they would seize the moment and try to decolonize their country.

Back in San Juan, Rosselló’s New Progressive Party (PNP) is engaged in a squalid knife-fight over who now gets to be in charge. First, Rosselló appointed Pedro Pierluisi, a former lobbyist for a coal company that polluted the island’s groundwater with toxic ash and a lawyer for the Fiscal Control Board, as secretary of state—making him next in line of succession even though he had not been confirmed by both houses of Congress. The Puerto Rican Supreme Court put a stop to this apparent coup attempt when the justices overturned his appointment on August 7. Then the job of governor fell to Wanda Vázquez, Rosselló’s justice secretary, who has herself faced criminal charges for corruption, despite the fact that she has repeatedly said she does not want the job.

In the leadership vacuum created by Rosselló’s disgrace, American newspapers like The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal have editorialized why additional powers should be granted to the very Fiscal Control Board that the protesters wanted to dissolve. “Before the whole situation with Rosselló unfolded, the conversation in D.C. was toward a bill to end PROMESA,” said Manuel Natal, a member of the Puerto Rican House of Representatives who is affiliated with the new progressive party Movimiento Victoria Ciudadana, referring to the 2016 law that created the board. He went on:

Now the needle has moved in the opposite direction. We’re calling for more democracy in PR, not less. The conversations about the possibility of a federal coordinator to act in the place of the governor, as was the case before 1952, would be another confirmation of what we already know. We are a colony of the US. They do with us how they please.

Puerto Rican party politics are dominated by the question of the island’s status vis à vis the US. Voters choose their party based on their preferences for statehood, independence, or the current “commonwealth” status. While these options presented by the parties were seldom mentioned in the protests, Puerto Rico’s colonial condition underpinned everything they were fighting against. One common slogan was Ricky, renuncia, y llévate a la junta (“Ricky, resign, and take the junta [Fiscal Control Board] with you”). Ricky did resign: a spoiled and venal colonial administrator, he had grown too embarrassing for his bosses to continue to back. But llévate a la junta? The junta is firmer than ever, and only the US Congress can dismantle it.

Puerto Rico is a colony, and as such, its government has only those powers the US Congress grants it. Puerto Rican legislators might protest the closing of their schools, the cutting of their pensions, or the gutting of the great university that has produced so many of the island’s most subversive and iconic leaders, but ultimately, the junta and Congress overrule them. When I asked about what it would take to llévate a la junta, activists offered me two options. First, the 5 million-strong Puerto Rican diaspora now living in the US could make Puerto Rico a political issue, advocating for their families on the island, who, as colonial subjects, are not allowed to vote in federal elections. Second, Puerto Ricans can make the island ungovernable.

Advertisement

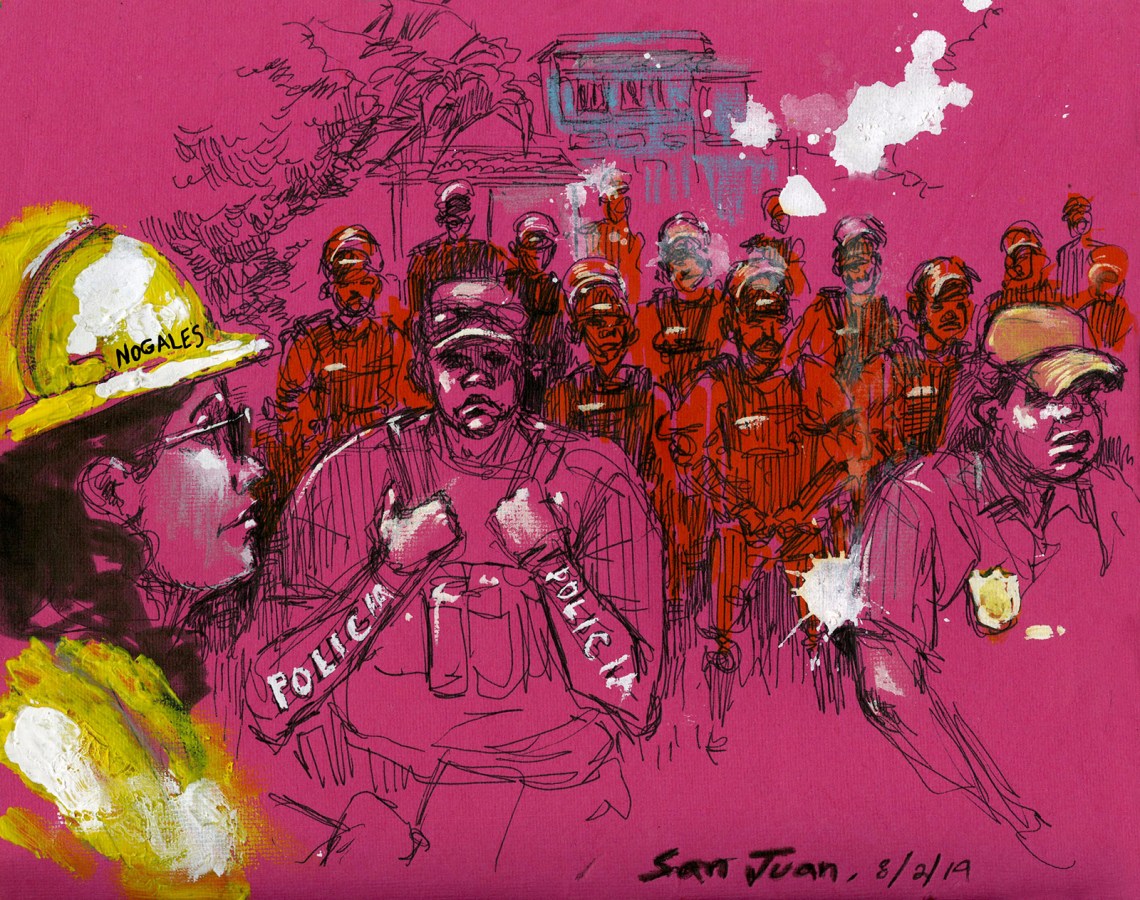

On August 2, the day Rosselló officially left office, protesters crowded in front of La Fortaleza, banging their pots and pans, singing old songs and new ones, counting down the minutes as though it was New Year’s. The names Calle de la Resistencia and Calle de la Revolución had been scrubbed off the walls, but the protesters held signs rejecting Pierluisi, Wanda, colonialism, the junta. A woman served portions of roast pig to the protesters, then walked around holding the pig’s severed head, a bandana printed with the words “Ricky, renuncia” in its mouth. The whole activist constellation was out: queers and socialists, environmentalists and independentistas, all the people who had marched alongside one another for so long that, up until this summer, protests felt more like family reunions. There were drag queens. There were members of the teachers’ union, whose retirees were seeing their pensions cut. There were organizers against toxic ash dumps. There were feminist activists with tape over their mouths holding hands. And there were flags: the once-banned Puerto Rican flag, now ubiquitous.

The flags were still there later that night, when a few blocks over, near the old city walls of Viejo San Juan, a teacher screamed in the faces of riot cops all kitted up in shiny black. “Don’t use violence,” she yelled, pointing in their visored faces, while behind her stood a mass of beautiful young people whose own faces were concealed behind goggles, bandanas and gas masks. Anticipating more tear gas, I put on my own goggles, which began immediately to fog in the heat, to draw the unfolding confrontation. The riot police pushed forward. In front of them stood young women, all at least a head shorter than the heavy-set cops. The girls linked their arms to make a wall. The police shoved. The girls held up their skinny arms. The police did not break through.

As I watched the young women hold back the cops, I thought how incomparably fine this place was, a fineness I can only describe using old fashioned, sentimental, Spanish words like fuerza and valor. This fineness was there in spite of Maria, in spite of the corruption, the mendacity of the political class, the downed power lines, the concrete suburbs, the McDonalds and Walmarts, its whole condition as a colony, whose masters, whether Spanish or American, had eventually abandoned it to desuetude.

It was this fineness that Ricky had never recognized. How could they have been so blind to it, these mediocre blanquitos with their ill-fitting suits, who were so ill-suited for the positions of power they occupied? Yet how could it be otherwise? If there was one thing the chats revealed, it was their contempt for their own people. How they hated Puerto Ricans, and as for Puerto Rico, it was nothing but a place to bleed. After a stint in government, they could retire to McMansions in an American suburb and live as lobbyists, secure in their belief that they, too, qualified as white Americans.

Sometimes, even those mediocre politicians realize how bad brute force can look in the international news. The police did not fire tear gas that night.

The next day, after the Caguas asamblea, I had drinks with a writer named Jefry López Pagán. “People think Puerto Ricans aren’t serious?” he demanded, thinking of all the American press reports that had marveled at the protests for their music, color, and dance. “Well, after all these years of colonialism—Spanish, American—we have learned to celebrate in spite of it all. What is Bomba but a people’s cry of indignation?”