“You wanted a fresh, dumb designer and, God help you, you found one,” wrote Maurice Sendak (1928–2012) to Frank Corsaro of their early collaboration on The Love for Three Oranges (it opened at Glyndebourne in May 1982). In 1978, the opera director had first commissioned the middle-aged author to devise the sets and costumes for a production of The Magic Flute that premiered at the Houston Grand Opera in November 1980. Sendak protested: “I had no idea how to do such a thing.” Nevertheless, Corsaro had correctly intuited that the illustrator’s exceptionally inventive visual storytelling skills, his ability to represent the darkness in one of the Grimms’ grimmest of stories for children, The Juniper Tree, which he was reading to his son at the time (child abuse and decapitation loom large), would be well matched to the opera’s sinister fairytale.

What Corsaro did not know was that Mozart was Sendak’s favorite composer—“a god I could really respect, because he was an artist”—and that The Magic Flute was his favorite opera. Sendak was to create designs for a dozen more stage productions over the next decade alone. Five of the most important—The Magic Flute, Where the Wild Things Are, The Cunning Little Vixen, The Love for Three Oranges, and The Nutcracker—are documented in an exhibition, now at the Morgan Library & Museum, of some 150 sketches, studies, and finished watercolors as well as dioramas, props, and costumes taken from among some nine hundred designs for those productions bequeathed to the Morgan by Sendak’s estate in 2013. (Their display here is also supported by loans from the Maurice Sendak Foundation.)

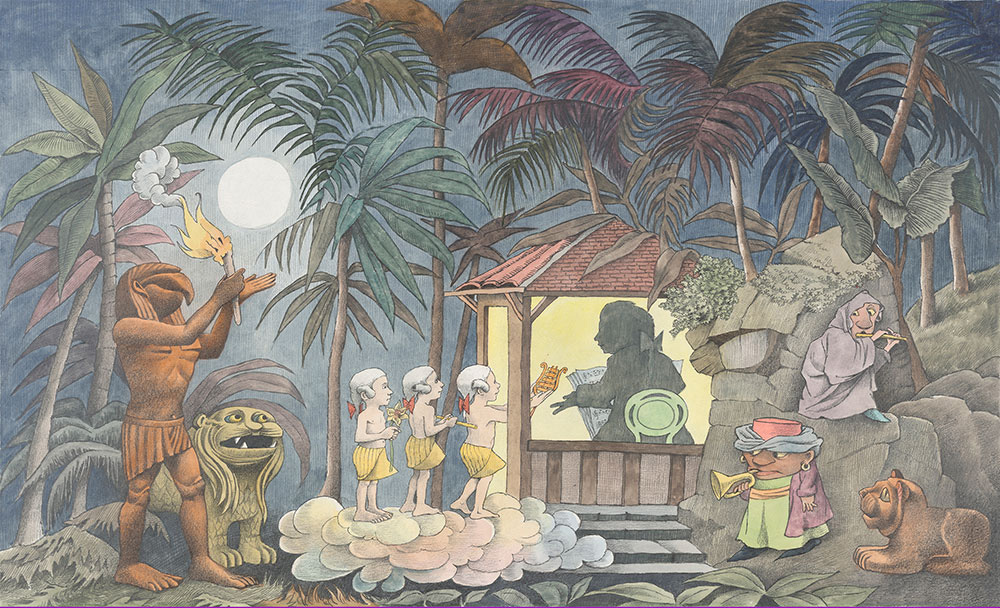

The first work you see as you enter “Drawing the Curtain: Maurice Sendak’s Designs for Opera and Ballet,” the diorama for The Magic Flute showing Prince Tamino in front of Sarastro’s temple (from which he hopes to rescue Pamina, daughter of the Queen of the Night), is an exemplary introduction to many of Sendak’s discordant preoccupations, fetishes that the world of musical theater allowed him to explore at a whole new level. For, like many of the other little-known designs here, this particular theatrical contraption shows Sendak fusing Baroque scenographic methods with motifs reflecting his own formidable erudition, his eclectic range of artistic tastes, ranging from antiquity (or riffs on it) to old movies, and, not least, his interest in historic books, toys, tchotchkes, and devices of all kinds.

Sendak’s use of painted scenery comprising wings, borders, cut cloths, and flats in this production, for example, allowed him to evoke the stagecraft of the inaugural production of The Magic Flute in 1791. Meanwhile, the Egyptian(ish) statues and hieroglyphics reference the role of such motifs in Freemasonry, as well as specific objects from the tomb of Tutankhamun. But with this mishmash of historic structures, styles, and exotic foliage, Sendak, who wrote about seeing Disney’s Pinocchio and Fantasia (both 1940) as among the fundamental artistic and emotional experiences of his Brooklyn childhood, also created what looks suspiciously like a scene out of a Hollywood Old Testament extravaganza. (One can almost picture the crumbling stonework falling—and bouncing.) And the proscenium arch, decorated with Egypto-kitsch and filtered through an Art Deco lens, might equally have been lifted from one of the 1930s moviehouses of Brooklyn.

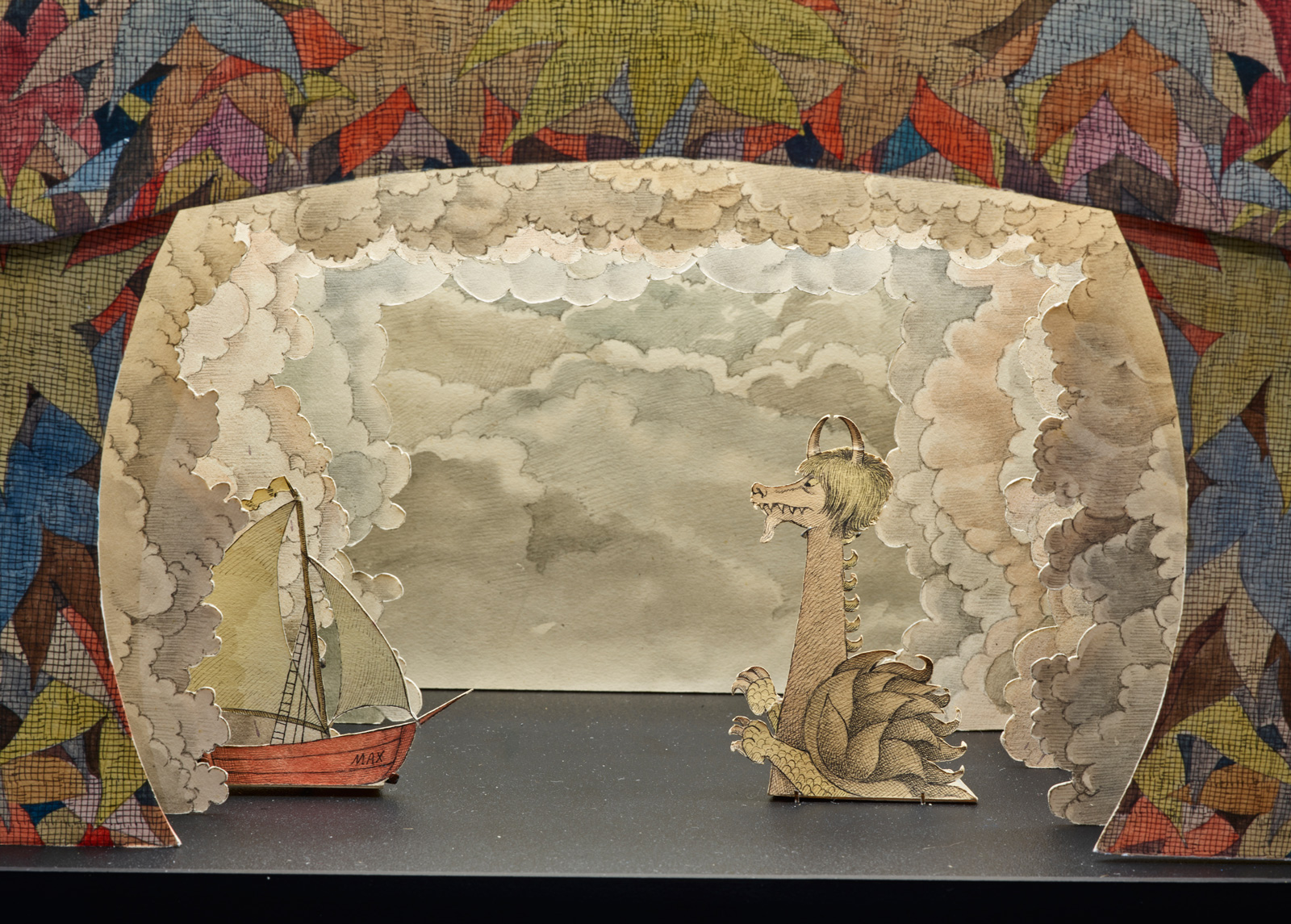

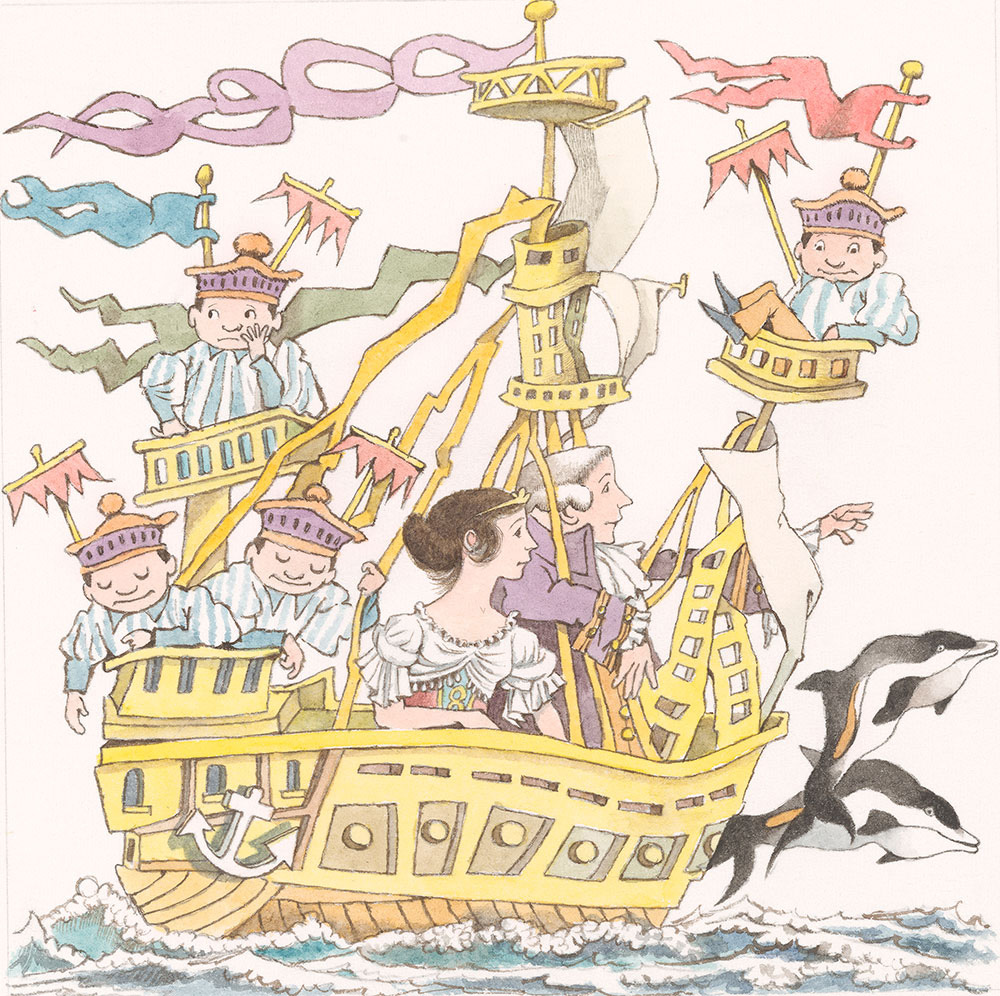

This motley assemblage nonetheless conjures something oddly familiar. For in his scenography for The Magic Flute (and other productions), Sendak devised, in effect, a series of giant pop-up books. The illustrator’s two-dimensional approach not only evoked historic stagecraft but enabled him to transfer illustration to the stage in the most direct and highly intentional way. Young Tamino alone in a scene framed by trees is decidedly reminiscent of an illustration from Wild Things (“That very night in Max’s room a forest grew”), but here animated. In two beautiful dioramas for the musical of Wild Things (a 1984 London production with Corsaro), both Max and the sea-monster spring up from the stage as two-dimensional figures set against layers of scenery that merely hint at a sense of perspective. In Sendak’s 1983 Nutcracker in Seattle, too, Clara rode in a ship as two-dimensional as the one in the design for it on waves created by layers of painted flats.

Indeed, Sendak had always been fascinated by the pop-up books of his own childhood as well as the mechanical books of an earlier era, like Lothar Meggendorfer’s International Circus (1888). As the playwright Tony Kushner has noted, “It is only on the stage that Sendak characters actually move among Sendak forests, houses, and ruins… But for all their depth, sound and motion, for all their atmospherically evocative power, [his designs] evoke nothing more powerfully than they do the book illustrations of Maurice Sendak.”

Advertisement

This is actually the fourth exhibition of Maurice Sendak’s work at the Morgan—and the most comprehensive of them. The museum was offered many of his stage designs, the exhibition’s curator, Rachel Federman, told me, but for reasons of space it focused on these five major productions. The special thing here is the chance to look at them alongside the works in the Morgan that directly inspired them, not least those from its distinguished collection of William Blake’s watercolors, drawings by the Tiepolos (père et fils), and music manuscripts. We are offered an unusually intimate understanding of the artist’s long history with the museum, as well as of his relationship to the work of specific artists.

In 1977, seeking a “color clue” for his preliminary drawings for Outside Over There, an unpleasant tale of an infant snatched away by goblins, Sendak “sat and looked through a magnifying glass at Blake’s illustrations for Milton’s ‘L’Allegro’ and ‘Il Penseroso,’ a suite of illustrations that I’ve always loved.” He began work on The Magic Flute in the next year, and the influence of Blake’s watercolors on those designs is evident. The diaphanous blue in the night sky of Blake’s The Goblin (circa 1816–1820) from L’Allegro, for example, is reflected in the background of the show scrim for the opera. Mozart is shown in silhouette on the scrim in the forest cabin in which he composed The Magic Flute, a structure apparently inspired by the simple wood-framed building also found in The Goblin. (Mozart in his Blakean cabin also appears, unaccountably, in a cameo role in an illustration in Outside Over There.) And in his design for the Temple of the Sun backdrop for the finale, Sendak seems to have adopted the pastel colors and luminous rainbow of Blake’s Milton’s Mysterious Dream.

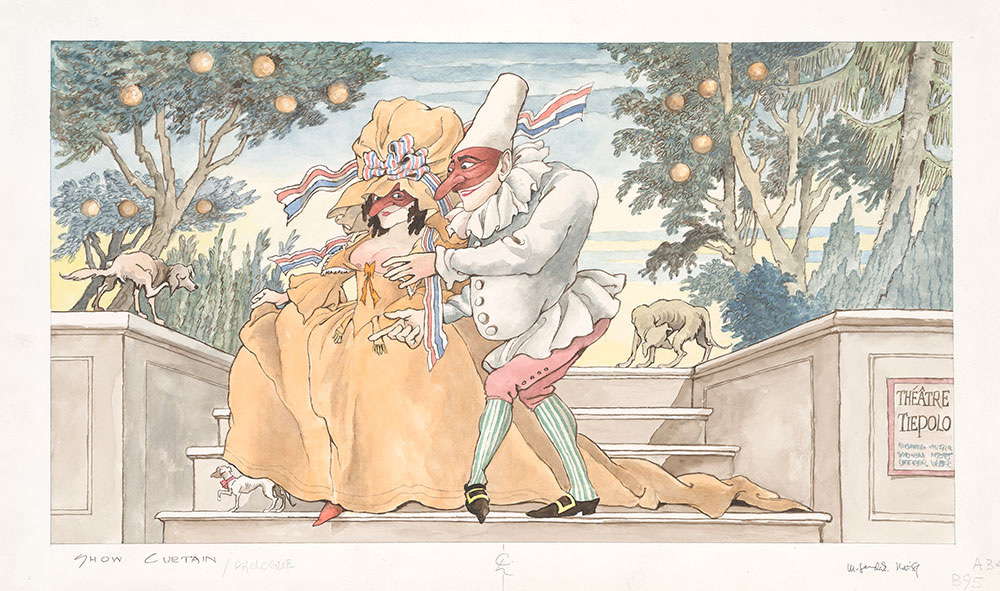

But while Blake and Mozart were preeminent in his artistic canon, Sendak borrowed most directly and shamelessly from the work of the Tiepolos in his designs for Prokofiev’s The Love for Three Oranges (another Corsaro production, which opened at Glyndebourne in 1982). He directly quotes Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo’s pen-and-ink drawing of The Chaperoned Visit, cheekily posing the mincingly genteel young couple as the Fata Morgana, the evil witch (here with a bonnet even more absurd than her prototype’s), stepping forth with her rival, the foppish Tchèlio. He also lifted from both Domenico Tiepolo’s Punchinello Beside a Villa Wall and Giovanni Battista Tiepolo’s famous drawing of the Drunken Punchinello to create a composite version for the curtain accompanying the march section of the opera.

“It is an odd matter indeed,” Sendak wrote to Corsaro at the time, “this almost magical union that occurs between stealer and stealee; it is as though I know what I want but can see it only inside (in this case) a Tiepolo drawing and then I can draw it out and make it quite properly my own.”

Notably, too, the sense of lurking menace that removes Sendak’s children’s books from the realm of the saccharine (one of the attributes that had attracted Corsaro in the first place) seeps into his stage work. It can be found in the scenery flat for Three Oranges, with its horridly grinning skeleton boat crew and in the gloomy ruins that haunt scenes from New York City Opera’s The Cunning Little Vixen (1981, again with Corsaro), probably inspired by the Romantic landscapes of Caspar David Friedrich and Samuel Palmer. Sendak even resisted The Nutcracker’s traditional “confectionary goings-on” in favor of a more sinister and erotic tale, closer to E.T.A. Hoffmann’s original story.

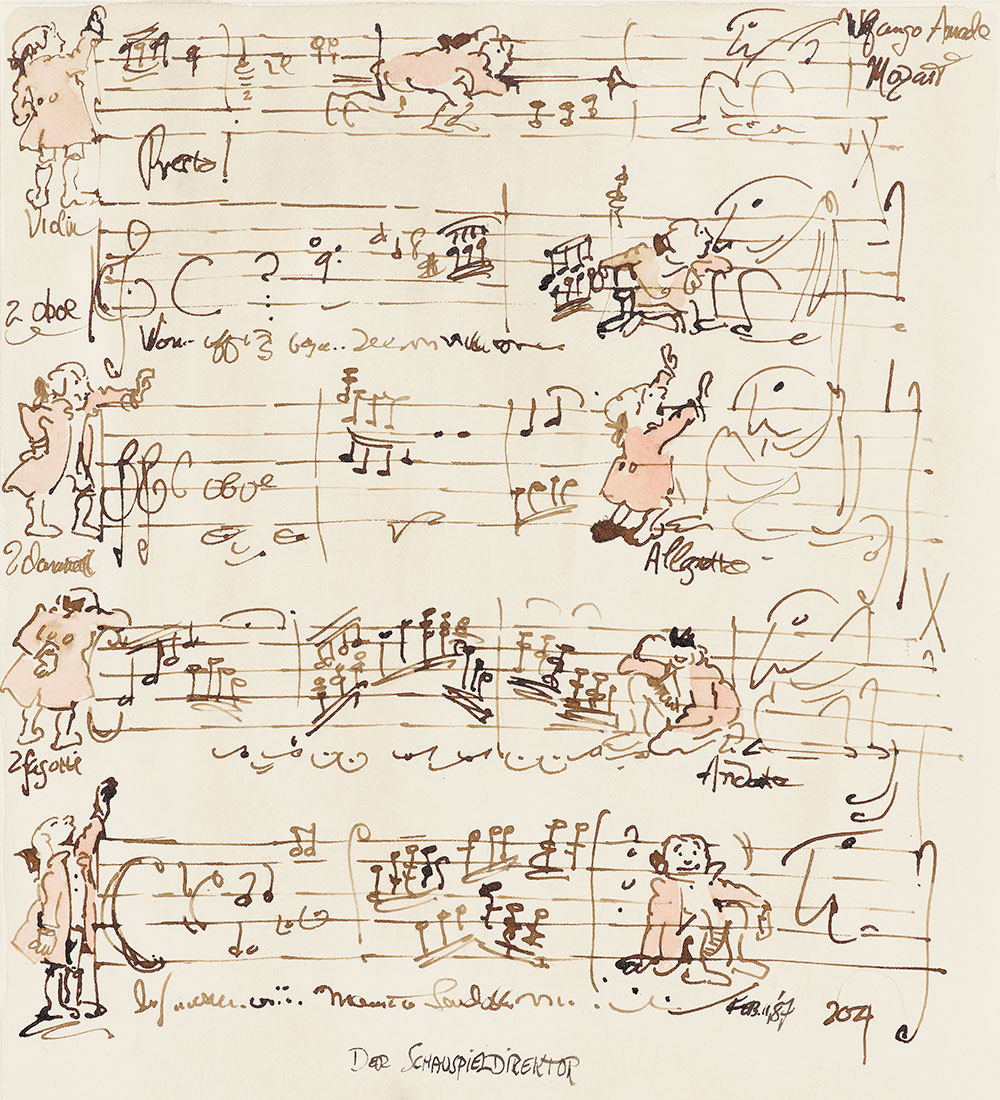

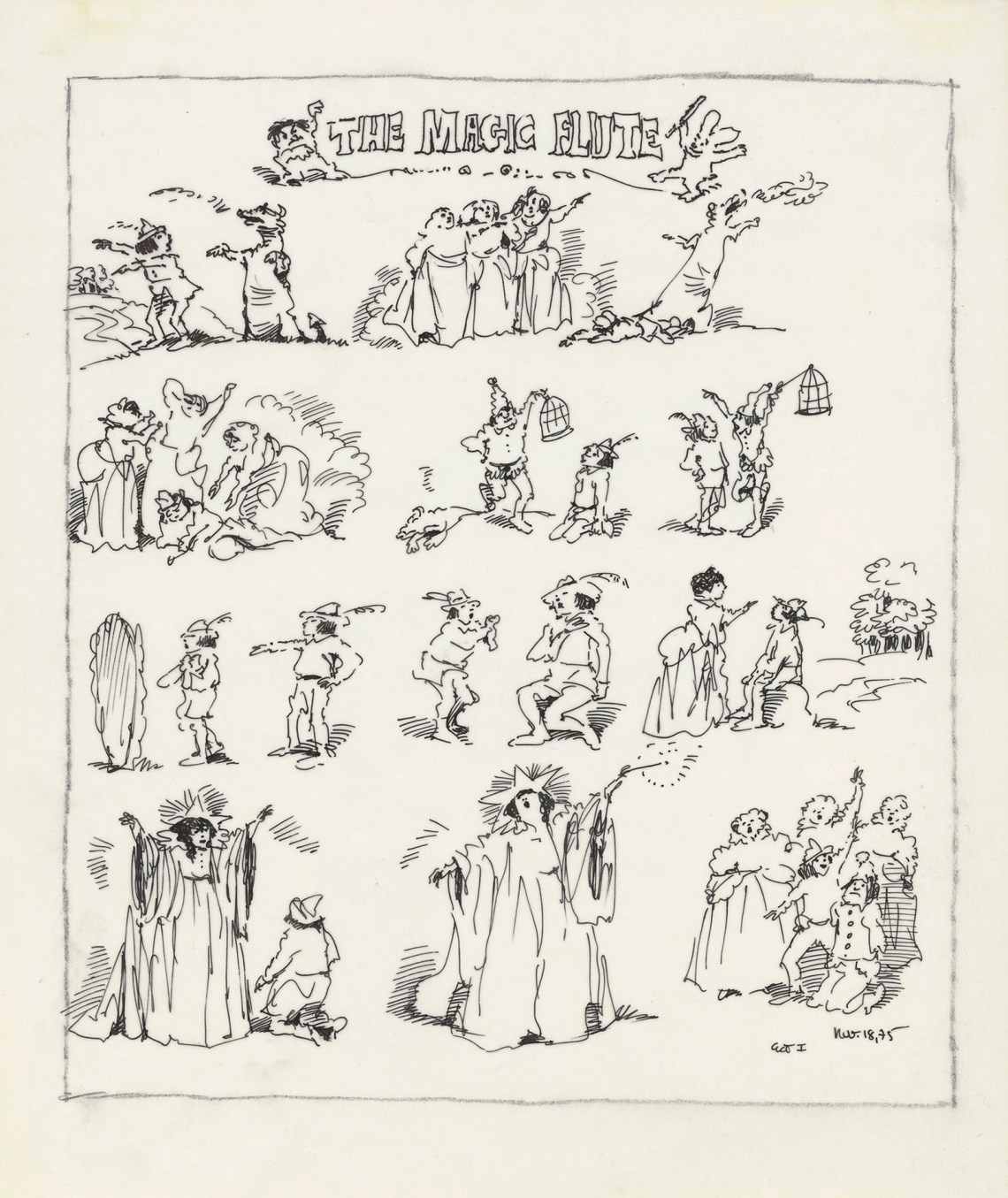

But the creepiness is tempered by much joy, especially in the storyboards. These reflect both Sendak’s initial ignorance of the conventions of stage design and what he called “the perfect good” of “hauling into my theater designs all the vast repertoire of my life as an illustrator.” Sendak had long created little storyboards of “fantasy sketches,” tiny sequential vignettes relating to favorite pieces of music. Among the most delightful is one for an imagined production of The Magic Flute, on which he had already begun working in 1975, and another for Mozart’s Idomeneo.

Advertisement

In both, the work of Sendak’s great musical hero has been subverted by the illustrator’s own peculiar comic sensibility—to glorious effect. In the Magic Flute sheet, the Queen of the Night stands in the foreground, her arms extended and head thrown back like an aging pop diva on a comeback tour. In the Idomeneo drawing, a figure in eighteenth-century dress removes the top of his sea-serpent costume, the head of which nonetheless intimidates a small group of onlookers. The finished storyboards for productions such as Wild Things and Three Oranges even show the little scenes divided into cells like those in a comic strip or an animated film.

Sendak himself identified the “crappy toys,” “tinsel movies,” and comic books of his childhood as “the only art I grew up with… and for some reason I find it very important.” A moving drawing by Sendak at the end of the exhibition, along with Mozart’s manuscript for Der Schauspieldirektor that inspired it, shows the great composer bounding through the illustrator’s version of the script as if in a Disney cartoon short. For all the revelations of this extraordinary exhibition, it is this drawing and Sendak’s sheet of watercolor costume studies for insects from Cunning Little Vixen (1981) that have remained most vivid for me.

These tiny human figures in bug costumes, each type meticulously labeled “grasshopper,” “ladybug,” “various beetles,” and so on, will not be corralled. Instead, they blithely cavort, negotiate, gossip, and dance in unison in little chorus lines across the page—it’s a sublime Sendak-style nuttiness that I defy you to resist.

“Drawing the Curtain: Maurice Sendak’s Designs for Opera and Ballet” is at the Morgan Library & Museum through October 6.