Berlin, Germany—On a Tuesday night in October, Kiez Bingo in the Kreuzberg area of Berlin is getting rowdy. “We play for a good cause and to get drunk,” proclaims the community event’s Facebook page. On this evening, the good cause is Welcome United, an activist organization that advocates for freedom of movement and radical reform of migration policy, and the place is crammed with people. Eric, a twenty-six-year-old Cameroonian volunteer, takes the stage. He speaks first in German, and then in English, ending with a protest rally cry: “No human being is illegal.”

Eric descends the stage stairs, beaming because he was able to deliver his speech in German, his fourth language. He checks in at the donation table, and then heads out down the street to Kiez Kantine, another neighborhood program of Welcome United that offers a weekly dinner to German locals and recent immigrants alike.

Eric has lived in Germany for three years, but his situation is precarious (which is why I am using only his first name). Immigration authorities tried to deport Eric back to Cameroon in late 2017, after his first asylum claim was denied. On a plane at Berlin’s Tegel airport, Eric started shouting that he didn’t want to go back. Eventually, the pilot stepped out of the cockpit. “Take him off the plane,” the pilot said. “I’m not flying with him on board.” Eric then found an immigration lawyer and appealed his case, albeit without success so far; he is now waiting for a decision on his third appeal.

Eric is one of more than 230,000 asylum-seekers and migrants who have been told they must leave the country but who seek ways to remain. His time here has coincided with a series of sudden seismic shifts in German society, as the country has engaged in a series of impassioned and sometimes ferocious debates over immigration following the government’s 2015 decision to temporarily open its border to asylum-seekers and admit close to one million people at the height of what became known as “Europe’s refugee crisis.” Foremost among these arguments has been the return of an old “integration debate”—about whether people from non-European countries can successfully become part of German society—even though no one can agree on what exactly German society is.

*

A small group of teenagers from Syria, Afghanistan, and other countries mingled in late September with adults in the courtyard of an old warehouse near the Spree river. The building is part of a nonprofit known as S27 (short for Schlesische 27), which supports arts education for young people, including refugees. They were there to celebrate the first anniversary of Clan B, a small youth group for teenagers who came to Germany without their parents.

Alaa was behind the bar serving tea, coffee, and beer. Now nineteen, Alaa reached Berlin after journeying from Damascus in late 2015 (a few months before Eric arrived). Alaa was fifteen, a shy, lanky teenager, at the time he was granted asylum. (Alaa also preferred that I used only his first name.)

S27’s history mirrors that of contemporary Berlin. The organization started in 1978 as the German-Turkish Youth and Cultural Center. In the 1960s and early 1970s, some 750,000 Turks immigrated to Germany on guest-worker visas. Although Germany had initially said they would have to return to Turkey after three years, the authorities later relaxed its immigration laws for a limited period; as a result, there is today a large Turkish population in Berlin, and 3.4 percent of Germany’s overall population has Turkish roots. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, S27 focused on bringing together young people from East and West; more recently, it has concentrated on supporting recently arrived refugees and immigrants from the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. In addition to providing job-training through craft apprenticeships, S27 also hosts small startup initiatives, like Clan B.

Alaa wasn’t formally a member of the youth group, but he was there to support his best friend, Amjad, who is also from Syria. Alaa told me he left Damascus after Syrian security forces started pressuring him to join the army (there is widespread evidence that the Assad regime has pressed boys as young as nine into military service as the civil war has ground on). At his family’s urging, Alaa left Syria along with his seventeen-year-old sister, traveling on foot into Turkey, taking a boat to Greece, and going on, by a series of buses and trains, to Berlin. Upon arrival, the siblings spent a few weeks in a hostel on Landsberger Allee before being assigned to refugee housing on the city’s outskirts.

“It was not nice,” said Alaa. “The walls were very thin, and I was afraid to leave my sister alone by herself.”

Advertisement

But one good thing came out of the temporary situation: Alaa met Amjad, and before long they were best friends. Now, if Alaa is sick, Amjad makes him soup; when Amjad needs a break from his house, he comes and stays with Alaa. Together, they’re a unit, navigating Berlin’s bureaucracy and dark winters.

“You can’t describe what it’s like to live as a foreigner in a country you don’t know anything about, not even its streets,” said Alaa. “I should have been home, playing with my friends. I didn’t get to see my siblings grow up. I lost that part of my life.”

By now, Alaa speaks German almost fluently (unlike many migrants from Australia, other European countries, or the US—such as myself) and is working in an apprenticeship program as a hospital aid, in which he makes 1,200 euros a month. Out of this stipend, he pays his rent and living costs, though it’s not much to live on in a city where the cost of living is rising. This fall, Alaa worked in a nursing home. When he has free time, he plays “Temple of Doom” and listens to music, or he visits his sister, who also received refugee status, for a meal. Still, even as he tries to make Berlin home, Alaa feels like a perpetual outsider.

“It’s not difficult to meet Germans, but it’s hard to interact because everything is different,” Amjad explained one night in a Dunkin’ Donuts on Alexanderplatz, with pop music blaring in the background. “There’s a barrier between us and them.”

“How people treated us started to change,” said Alaa, sipping from a giant cup of coffee. “They started to blame the problems that one person would make on all of us.”

*

In late August, I drove through the southern state of Saxony, where telephone posts along the back roads were plastered with posters from the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) and other far-right parties, advocating for stronger border control in advance of regional elections and even “Saxit,” a Saxon exit from Germany. Today, the AfD’s strongest support remains in the formerly Socialist and once Soviet-occupied eastern states, which, despite the vaunted success of reunification, have long felt disconnected from what was West Germany.

The AfD has capitalized on this divide and the real issues faced by Germans in the East—in particular, higher unemployment and rapid depopulation as young people have moved westward—through a virulent anti-immigration campaign, including an ongoing effort to link migrants and refugees to crime in the German imagination. Refugees and migrants do commit crimes, of course, just as any other segment of a population does: according to the most recent German government analysis, in 2018 refugees, asylum-seekers, and undocumented immigrants comprised 8.6 percent of general crime suspects, 12 percent of sexual assault suspects, and 15 percent of murder suspects. These rates are higher than the percentage of the German population (approximately 2 percent), but the raw data should be viewed with caution as criminologists point out that gender and age are major factors: young men commit more crimes in every society. (For example, back in 2014, young German men comprised only 9 percent of the population but were responsible for half of all crimes of violence.)

Yet nuance has been, unsurprisingly, lacking in some of Germany’s mainstream media. According to a 2017 study from DPA, the German press agency, national media were more likely to cover a crime when a refugee or migrant had committed it. The study found that broadcast networks had 50 percent fewer reports about non-German victims of violence in 2017 compared to 2014—despite evidence that violent crimes against this group had risen. This bias in media attention is exploited by far-right politicians and amplified by the echo chamber of social media.

“Keyword squatting” is a phrase coined by the Harvard scholar Joan Donavan to explain how a seemingly neutral term like “migrant” becomes associated on social media with an additional connotation such as “criminal.” Research into the effects of disinformation campaigns has further revealed that once a person absorbs a piece of information, it can have a lasting impact on attitudes and beliefs regardless of its veracity.

In Germany, far-right parties have found a receptive audience on Facebook and other platforms to spread misinformation about refugees and migrants. As of early November, the top ten German Facebook pages and groups with the most shared content about migrants, refugees, and asylum-seekers were all either German far-right groups or alternative and conservative media sites (these include the Epoch Times, a site that, according to the media watchdog NewsGuard, publishes false content and “promotes debunked conspiracy theories”; Tim K., a former police officer and right-wing social media personality; and the conservative-leaning tabloid Bild). Five of the top ten were associated with the AfD itself, including accounts like AfD-Gruppe Bundesweit, a page for AfD supporters. RT Deutsch (the Russian government-backed news channel in Germany) was another top performer, as were AfD politicians including the two co-chairs of the party’s group in the German parliament, Alice Weidel and Alexander Gauland.

Advertisement

Even outside the far-right media ecosystem, the majority of media articles linked to by the most popular Facebook posts portray migrants and refugees negatively, and more than half of the content was about their allegedly committing sexual or physical assaults or other crimes. The supposed sexual menace posed by migrants is a staple theme on these pages: “rapists,” reads one AfD ad plastered over an image of a ship carrying black people on the Mediterranean Sea. Other posts focused in a hostile way on the humanitarian groups that rescue people trying to cross the sea or on statements made by the German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

The edge of hostility that has crept into public discourse about foreigners has had its effects. Far-right hate crimes are on the rise in Germany: in the first half of 2019, 8,605 incidents were recorded—900 more than over the same period last year. According to a report from the Interior Ministry in May, the majority of hate crimes were committed against foreigners and were up nearly 20 percent. Anti-Semitic incidents are also on the increase: offenses rose by almost 10 percent in Germany last year, with violent attacks up by more than 60 percent.

None of this is news to Alaa. A few months ago, he was traveling on the S-bahn, an overground railway that runs in a circle around Berlin, when he noticed an older man staring at him. “Is everything OK?” asked Alaa in German. Glaring at him, the man shot back: “I don’t talk to foreigners.”

*

What makes someone part of a society? Is it speaking the language, understanding the laws and norms, having a job? Or does it also require feeling comfortable walking down the street and having a sense of belonging?

Over the past four years, one of the many debates about refugee integration has centered on German culture, and how refugees should assimilate to it. These discussions were not new, but they resurfaced for two reasons: in part because those in the center and on the left of German politics wanted to avoid the marginalization of new arrivals and the creation of parallel societies (as some claim happened with previous generations of Turkish, Lebanese, and Palestinian-Lebanese immigrants); and in part because the far right laid out a specific argument that Germany’s very identity as a nation was under attack from foreigners. Behind these concerns and anxieties is the fact that Germany’s demographics have been undergoing a long-term shift—nearly a quarter (23.6 percent) of the population now has an immigrant background.

In April 2017, the then-Interior Minister Thomas de Maiziere of the governing center-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) published an op-ed in Bild calling for the return of “Leitkultur,” or leading culture. Leitkultur originally stems from a scientific term used to describe the dominant plant varieties in a specific environment. De Maiziere argued that to be part of German society, one should adhere to German culture and values, for which he included a wide range of characteristics—from the broad, such as education and individual achievement, to the oddly specific, such as not wearing a burqa. According to de Maiziere, Germany was definitely Christian, part of the “the West,” and Germans were “enlightened patriots” that do not resort to violence in disputes.

De Maiziere’s argument was quickly rebutted by many across the political spectrum in Germany, including his boss, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who then published her own A-Z list on what it means to be German. Eager to articulate a more inclusive vision, Merkel recognized Germany’s Judeo-Christian roots while acknowledging the importance of Muslim and other religious communities. (She also mentioned bratwurst and punctuality.)

Still, the notion that there is something exceptional about European culture—an old idea that gained new currency in the age of empires and colonialism—has reared up again across the continent as a response to postcolonial migration. In September 2019, the European Union changed the job description of its migration commissioner to that of “Protecting the European Way of Life.” After the EU Parliament protested, “protecting” was replaced with “promoting.”

Many of the 1.06 million Syrian and other refugees granted asylum by Germany over the previous five years have received substantial state assistance to help them learn German and integrate into the labor market, as Alaa is starting to do. Germany spent an estimated 23 billion euros of its 343 billion euro federal budget last year on integration support. (In spite of this outlay, there was still an 11.2 billion euro budget surplus.) According to the government’s calculations, 35 percent of refugees who arrived in 2015 had landed a job by October 2018—no small feat considering a laborious process that does not recognize most foreign qualifications and requires new arrivals first to spend as much as two years learning German and a further two years in vocational training before they can even apply for a position.

Germany has an aging population, and its ability to sustain economic growth and meet its state pension obligations depends on allowing immigrants to become part of the workforce. One study estimates that already, in the next three years, Germany will reap in taxes from immigrant workers more than it spends on integration.

Yet as much as Merkel has fought, sometimes within her own party, for the right of Syrian and other refugees to remain and build new lives in Germany, she also wants to appear tough on migration—by speeding up deportations of rejected asylum-seekers, as well as “economic migrants.” The government has not proposed programs to allow for legal economic migration (such as another guest worker program); and for those like Eric who made it to Germany from Libya, it will not grant temporary work permits or provide integration support. It is an open question how effective the more restrictive policy has been. A report in the German newspaper Die Welt am Sonntag this month found that nearly 5,000 asylum-seekers who were deported from Germany over the past seven years later re-entered and applied again for asylum.

Instead, Germany, in line with the European Union, has shifted the focus of its immigration policy to funneling foreign and security aid to Middle Eastern and African countries in an effort to forestall people from moving. Merkel’s CDU has been in a fragile governing alliance with the center-left Social Democrats since 2017, and in an attempt to respond to the AfD’s rise has proposed a number of measures, such as a new 1 billion euro Development Investment Fund for Africa. In total, Germany spent some 8 billion euros last year on initiatives to cut migration by trying to improve the standard of living in countries where migrants originate.

The fact that thousands of people continue to move from West, Central, and East Africa through Libya, where many experience violence and abuse in detention centers, and then risk their lives to cross the Mediterranean Sea, as well as by other border points, to reach Europe poses a challenge to Germany’s governing consensus. Those who reach the country do not fall into neat categories: while some have fled economic scarcity, others are refugees from differing degrees of violence and persecution, but almost all are traumatized in one way or another.

*

Eric is originally from Douala, the business capital of Cameroon, the West African republic has been ruled by longtime dictator Paul Biya since 1982. Since 2016, a separatist insurgency has fractured the country, leaving thousands dead, half a million displaced, and some 1.3 million in need of aid. Today, the country ranks 150th out of 189 countries on the human development index, a UN ranking for standard of living; Germany is fourth. Cameroonian security forces, according to Human Rights Watch, torture detainees and conduct extrajudicial executions (there have also been abuses documented among the rebels).

Eric was persecuted back home, he says, though he preferred not to disclose details while his appeal is pending. He now lives in Brandenburg, a town that also gives its name to the mainly rural province surrounding Berlin, full of forests, rivers, and farms, that has seen support rise over the years for the far right. After September’s regional elections, the Afd became the second strongest party in local government.

Eric resides in a one-bedroom apartment in a sprawling gray building; for weeks after he moved in, he noticed that his elderly neighbor didn’t say hello in the hall, until one day when she saw him in a volunteer uniform for Die Johanniter, a local Christian charity (his middle name is Noel because he was born at Christmas). Now she and Eric chat regularly. Despite the tranquility of his surroundings, Eric says he can’t relax; he has to keep busy. Only constant movement takes his mind off his anxiety that he could be deported. That and the fact that he hasn’t seen his mother in over six years.

“She thought I was dead, two times,” said Eric. “She thought I’d died in Libya. When I checked my WhatsApp after several months, she had sent me a message that said, ‘Rest in peace, Eric.’ To see her again, it would be something I cannot describe.” Although Germany has a long-standing relationship with Cameroon, which it ran as a colony from 1884 to 1916, if Eric left to visit home, he would not be let back in. Cameroon, in fact, is one of the countries Germany is paying to take people back under “voluntary return” programs facilitated through the UN-affiliated International Organization on Migration (IOM).

For his part, Eric says he doesn’t want to go back to Cameroon. Living there, he said, is “like jail, but not like a physical jail—it’s like they force you to compress yourself.” The main feature of these voluntary return programs, which are advertised on the metro stations in Berlin, is that they pay participants a modest grant, around 1,000 euros, to leave. “I don’t want their money,” says Eric. “Even if it was 10,000, I wouldn’t take it. My freedom is worth more than money.”

To keep his mind occupied, Eric volunteers with an LGBTQ organization in Potsdam. He goes to community group meetings devoted to fighting racism and anti-migrant sentiment. He joined a local rugby team, which has given a structure to his days, though he’s also faced racism from some of the players. He is only the second black member to join the team, and currently its only one; the first, also a Cameroonian, quit before Eric arrived.

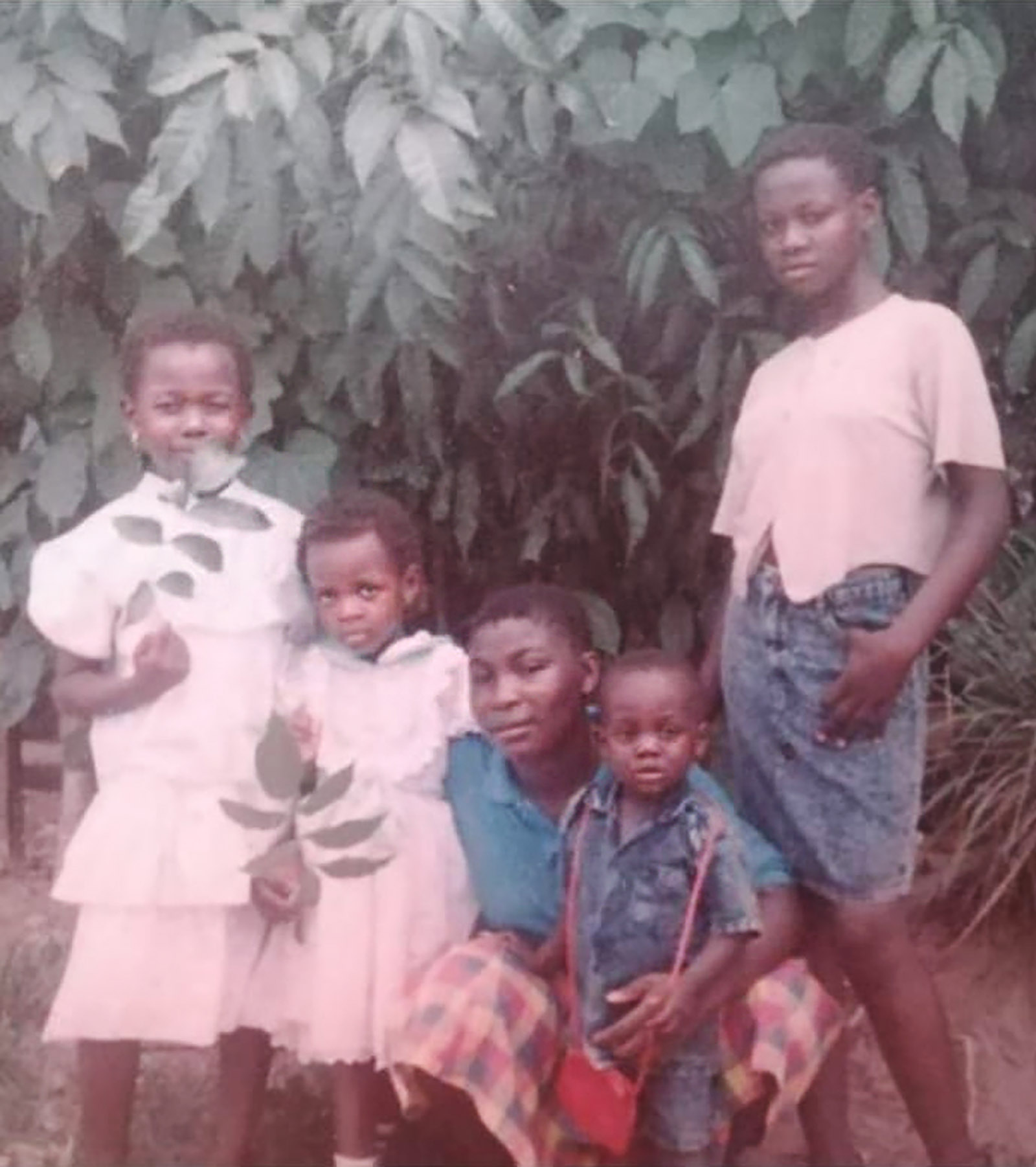

Earlier this year, Eric’s uncle called him from back home to ask him for money, because he was having health problems. Since Eric is not allowed to work, he receives only a small monthly stipend from the government (approximately 210 euros); he has nothing to save or send home. He had to say no, and a few months later, learned that his uncle had died. The guilt is something Eric carries around. On a tram into Brandenburg, he pulled up a photo on his phone of himself as a child with family members in a garden. Of the five people in the photo, only one is still in Cameroon. The others have scattered, to Italy, France, and America.

*

In 1994, the late British political theorist Stuart Hall delivered a series of lectures at Harvard on nations and diasporas. He proposed that everyone has a culture, and that there are cultural differences, but that what it means to be, say, Syrian, or Cameroonian, or German is constantly changing as people interact with each other. He described a country’s story about itself as a common way of creating meaning: “It helps us to see ourselves in the imaginary as somehow sharing in an overarching collective narrative, such that our humdrum, everyday existence comes to be connected with a great national destiny that existed prior to us and which will outlive us.”

We all want to belong, but when culture is used to exclude and divide, it hardens quickly into nationalism. The more a country tries to define its identity solely through culture, the more it turns in on itself. “The question is not who we are, but who we can become,” Hall said. Germany is poised uneasily in that polarity.

Each week, Eric takes a two-hour train journey from Brandenburg into Berlin to attend Welcome United’s Kiez Kantine. Sometimes, he helps cook; other times, he comes for the company. On a recent evening, the popular Tunisian song Sidi Mansour blasted in the kitchen as people gathered to chat. Outside, tourists and Berliners made their way to bars and clubs, oblivious of this modest attempt to create community for those who managed to make it inside.

This article received support from the EU-funded Migration Media Award. Additional reporting was by Raymond Serrato.