US Attorney General William Barr’s defense of unchecked executive authority in his recent speech to the Federalist Society had an unpleasant familiarity for me. It took me back to a time in my life—during the late 1990s, as a graduate student in England, and the early 2000s, teaching political theory in the politics department at Princeton University—when I seemed to spend altogether too much time arguing over the ideas of a Nazi legal theorist notorious as the “crown jurist” of the Third Reich.

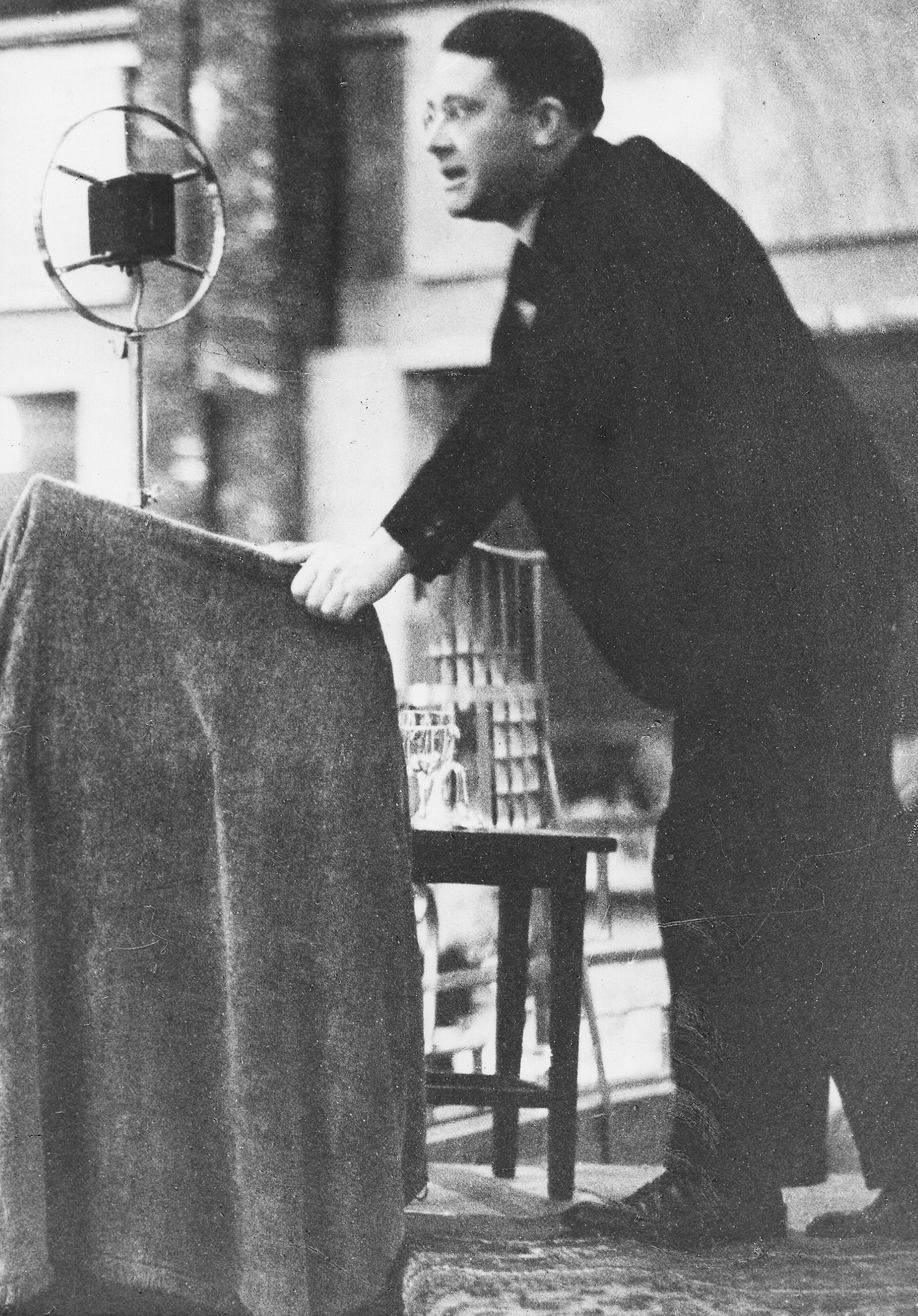

Carl Schmitt’s work had then become popular in universities, and particularly in law schools, on both sides of the Atlantic. The frequent references to his “brilliance” made it evident that in the eyes of his admirers he was a bracing change from the dull liberal consensus that had taken hold in the wake of the cold war. Schmitt’s ideas thrived in an air of electrifyingly willed dangerousness. Their revival wasn’t intended to turn people into Nazis but to rattle the shutters of the liberal establishment.

Schmitt was supposed to be a realist. For him, laws and constitutions didn’t arise from moral principles. At their basis, there was always a sovereign authority, a decision-maker. Schmitt stipulated that the essential decision was not a moral choice between good and evil but the primally political distinction between friend and enemy. And that distinction, in order to be political in the most important sense, had to generate such intense commitment that people would be prepared to die for it. He set out this view in a brief work, The Concept of the Political, in 1932. Only a few years later, he and many of his fellow Germans showed that they were prepared to kill for it. And kill and kill and kill.

In spite of his ideas’ serving this dismal role in recent history, I found that there were always one or two students for whom the simplicity of Schmitt’s dualistic choice was appealing. All the complex reflections and reasoning that enter into responsible political judgment could be dismissed in favor of one very simple binary opposition. We all want our justifications to end somewhere, to bring an end to the process of providing reasons for our beliefs, values, and actions, and those prepared to listen to an authority telling them exactly where that should be are unburdened. I liked to think that most of the students who embraced Schmitt’s work were attracted to the view merely as a theoretical position and were as lacking in real enmity as the anemic liberals whom Schmitt despised.

But in the same period that I encountered these tousle-haired Schmittians in flip-flops, there was in the United States a tremendous craving for action to avenge the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, and prevent further loss of American lives. Impatience at endless diplomatic wrangling, including the United Nations’ failure to take seriously the Bush administration’s case for invading Iraq, made simple decisionism and the idea of the unchecked executive ferociously appealing in US political life. The concept of the “enemy combatant” became sufficiently vague for the executive branch to apply it more or less at will to whatever person it pleased. And for many of those advocating pre-emptive war, or rendition and torture, on the grounds that terrorists might attack us with weapons of mass destruction, the sense of “it’s them or us” developed a new and ugly intensity.

The problem of containing the terrorist threat was not construed as one of detection and policing. It was a war. And for prominent thinkers and politicians on the right, it was a civilizational battle for “Judeo-Christian values” against “Islamo-fascism,” a friend-enemy distinction that remains deeply rooted in parts of American society today. This ill-defined enemy is the specter constantly evoked by the people Trump has chosen as his advisers and officials. Their mythic world-historical struggle has become detached from the actuality of counter-terrorism operations. General Michael Flynn, a veteran of the “global war on terror,” wrote in his 2016 book The Field of Fight:

We’re in a world war against a messianic mass movement of evil people, most of them inspired by a totalitarian ideology: Radical Islam. But we are not permitted to speak or write those two words, which is potentially fatal to our culture.

The idea that “evil people” might destroy “our culture” is alarmingly bellicose rhetoric, but one that is evidently persuasive for certain people. Steve Bannon uses it, too. He made a speech via Skype at a Vatican conference in 2014 in which he stated that “we are in an outright war against jihadist Islamic fascism.” These are just the beginning stages “of a very brutal and bloody conflict.” He called upon the “church militant” to fight this “new barbarity.” In the White House, Bannon’s main initiative was the racist and deeply harmful travel ban on people from Muslim countries. Trump’s Executive Order 13769 restricted entry to the United States for citizens of Iraq, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen on the grounds—disputed by most counter-terrorism experts—that it was an essential counter-terrorism measure.

Advertisement

So the views expressed in Barr’s Federalist Society address were not new ones. Not only has this Schmittian approach to constitutional doctrine come to be accepted as one respectable view among others in law schools, it has become increasingly accepted as a feature of American politics as well. Barr described the travel ban as “just the first of many immigration measures based on good and sufficient security grounds that the courts have second guessed since the beginning of the Trump Administration.” The president, when acting, or claiming to act, in the interests of national security, should be allowed unlimited scope for decision-making. Barr told his audience that the Framers’ view of executive power—

entailed the power to handle essential sovereign functions—such as the conduct of foreign relations and the prosecution of war—which by their very nature cannot be directed by a pre-existing legal regime but rather demand speed, secrecy, unity of purpose, and prudent judgment to meet contingent circumstances. They agreed that—due to the very nature of the activities involved, and the kind of decision-making they require—the Constitution generally vested authority over these spheres in the Executive.

Constitutional experts have denounced this view of the unchecked executive not only as a misinterpretation of Article II of the Constitution, but as a dangerous attempt to place the president above the law.

Barr’s view is the final reductio ad Schmitt of our political era. As US attorney general, at the head of the Justice Department, he is charged with upholding the rule of law, but he admires only lawlessness in moments of crisis. He claims in his Federalist Society speech that America’s greatness has been achieved through its most savage conflicts, from the Civil War, through World War II “and the struggle against fascism,” to, most recently, “the fight against Islamist Fascism and international terrorism.” Barr even folds into this narrative the “struggle against racial discrimination,” while using his office to defend a blatantly racist president. These “critical junctures” when the country has been most challenged, he claims, are the moments that have brought the Republic “a dynamism and effectiveness that other democracies have lacked.” Such moments of decision gained that significance precisely because this was when the presidency “has best fulfilled the vision of the founders.” By this, Barr means the urgent, secret decisions that forge a strong and vital sovereign authority.

This is not just a theoretical position for Barr. He previously supported President George H.W. Bush’s pardoning of Caspar Weinberger, Reagan’s secretary of defense who was charged with obstruction of federal investigations and lying to congress about the Iran-contra affair. That reckless criminal enterprise presumably represented the kind of “dynamism and effectiveness” that the liberal rule of law tries to suppress. Barr admires action.

He also fears that the commitments motivating sovereign decisions and actions will become etiolated if removed from the sustaining light of Christian faith. Religion is the only basis, he has claimed, for the kind of commitment that is conducive to greatness. In a recent address at Notre Dame, Barr poured contempt on the “high-tech popular culture” that distracts us from our fundamental commitments. Willfully disregarding the First Amendment’s establishment clause, he told his audience that “as Catholics, we are committed to the Judeo-Christian values that have made this country great.”

Barr claims to have extremely high-minded motivations. Unlike the frivolous and profane culture that surrounds him, he has understood how to lead a dignified human life:

Part of the human condition is that there are big questions that should stare us in the face. Are we created or are we purely material accidents? Does our life have any meaning or purpose? But, as Blaise Pascal observed, instead of grappling with these questions, humans can be easily distracted from thinking about the “final things.”

The “militant secularism” rampant in America, he insists, endangers this spiritual vocation. Will Barr be remembered, I wonder, for his determination to confront important and intractable theological and philosophical problems? Surely not.

He will be remembered, rather, for defending an impeached president who tried to bribe a foreign power to dig up dirt on his domestic political rivals. And for mischaracterizing Robert Mueller’s report into Russian interference in the 2016 election, then lending his support to the bizarre view, promoted by Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, that Ukraine was responsible for the electoral meddling. Barr may also be remembered for eccentrically jetting around Italy, Britain, and Australia, in an effort to gin up support for a baseless conspiracy theory about the “deep state” involving George Papadopoulos, a junior adviser to the Trump campaign and convicted felon. He will be remembered, too, for accusing the FBI of “spying” on the Trump campaign and for dismissing the Inspector General’s report that vindicated the FBI on the substantive issues on the same day that the president called the agency’s officers “scum.”

Advertisement

Like Barr, Carl Schmitt held a moralizing view of secularism and liberalism as inadequate to the true seriousness of life. But commentators have been puzzled by what this “seriousness” consists of and whence the demand for such deep enmity arises. The political philosopher Leo Strauss criticized Schmitt for implicitly resting “the political” on moral foundations, even as Schmitt claimed the realm of politics was entirely distinct from morality. One prominent German scholar, Heinrich Meier, made a very influential argument that this moral basis was supplied by Schmitt’s Catholic faith. The “ultimate values” that demand the “ultimate sacrifice” must derive from the hidden theistic basis of this thought. Is this what Schmitt has in common with Barr?

A more obvious explanation for Schmitt’s demand for enmity, for his condemnations of a liberal culture that weakens that hostile will and of the rule of law that obstructs it, is racism. He was, after all, not just a Catholic but a Nazi. His actions and unpublished writings betray a virulent anti-Semitism. We do not need to invoke an esoteric theism to account for what can be sufficiently explained by bigotry. And many would argue that in our own time the mythic crusade against the civilizational threat of “Islamo-fascism,” and the manufactured fear of the supposed barbarian hordes who must be prevented from flooding in from the south by an impregnable border wall, are barely disguised manifestations of a similar racism. It has nothing at all to do with the meaning of human existence, or “final things,” or anybody’s God.

The reality of the “war on terror,” though, is becoming further and further detached from the mythic crusade against “Islamo-fascism.” The greatest terrorist threat America now faces comes from domestic terrorists. And national security policy has pivoted away from the Islamic world toward more traditional geopolitical rivals such as Russia and China. We’re not engaged in a binary civilizational battle. As the myth becomes unsustainable, Barr and his allies will have to find a new enemy to justify their view of the president as the indispensable, unitary sovereign at the head of an executive branch that is perpetually on a war footing. They will be forced to ramp up the rhetoric of apocalyptic conflict—as Barr is indeed doing.

This doesn’t mean, of course, that they will need a foreign war (though, as the escalating confrontation with Iran shows, this may remain an option); all authoritarian regimes create their own internal enemies. No one should doubt Barr’s capacity and will to do this. In his original tenure as attorney general, from 1991 to 1993, Barr disbanded the counterintelligence team of the FBI that had been focused on the Soviet Union during the cold war but whose expertise and Russian language skills seemed less relevant in 1992. He instead turned the FBI’s attention to gang-related crime and violence and became a leading advocate of the mass incarceration policies that have since so disproportionately affected America’s black population.

And today, during his second tenure leading the Justice Department, in December 2019, he returned to these themes—apparently disputing the right of Americans of color to protest police violence. Law enforcement must be respected, he said, adding ominously that “if communities don’t give that support and respect, they might find themselves without the police protection they need.” In effect, he reserved the right to make decisions about who should and should not be afforded the protection of the rule of law, a notably Schmittian reflex.

Barr is not just another craven defender of Trump. Just as Carl Schmitt’s identification of parliamentary democracy’s weaknesses in the 1920s and his increasingly authoritarian rhetoric in that period had a basis that was quite independent of the cult of Hitler, so William Barr represents a cast of legal thinking (or perhaps, more accurately, anti-legal thinking) that has its own origins and supporters. One clear ally is John Durham, whom Barr has placed in charge of his inquiry into the FBI’s conduct in the Trump–Russia investigation.

Durham’s colleagues have constantly assured us of his integrity, but his natural tendency, too, is to speak in the crudest terms of friends and enemies. In a lecture to the Thomistic Institute at Yale University in November 2018, Durham was discussing his investigation into the destruction of tapes showing CIA torture (an investigation that resulted in no indictments) when he chose to describe the alleged malfeasance revealed by the tapes as no more than “the unauthorized treatment of terrorists by the CIA.” This is a troubling description: as Durham must know, not all of the young Muslim men subjected to torture were terrorists. At least twenty-six of them were found to have been wrongfully detained. He also chose a bizarre analogy to describe his deeper motivations: he compared himself to the 1970s movie cop “Dirty Harry,” a white officer with little respect for due process who often shoots-to-kill black criminals and displays a sociopathic lack of conscience about doing so. Durham told his audience a story about Harry Callahan encountering a “black militant” who can’t comprehend Callahan’s unselfish motivation “to serve.”

Durham now serves a master who views lawless conflict—the “critical junctures” that “demand speed, secrecy, unity of purpose, and prudent judgment”—as the most important engine of progress, the vital heart of American power, that will bring a wider reckoning with “final things.” Independently of Trump and this presidency, William Barr, his henchmen, and his Federalist Society supporters represent a powerful threat to the fundamental values of liberal democracy.