In 1974, in a remarkable essay titled “The African Presence in Caribbean Literature,” the great Bajan poet Kamau Brathwaite reflected on the sometimes striking ways in which Caribbean cultures contained traditions and rhythmic patterns resembling those in West Africa. For Brathwaite, it was impossible to understand contemporary Caribbean—and, for that matter, African-American—culture without examining these African traditions, which had been transmitted across the Atlantic and transformed during the bloody centuries of the European slave trade. The Caribbean’s cultures were not entirely the same as their origins an ocean away, of course, but inextricably interwoven into their fabrics were the African religious images, cadences, and terpsichorean rhythms that had traveled from the shores of West Africa to the West Indies.

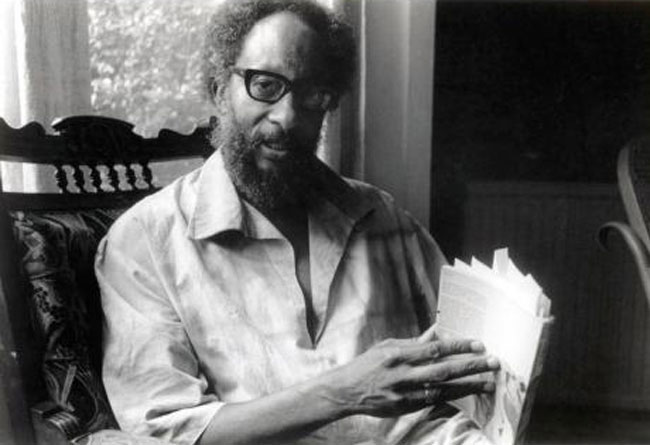

Yet as Brathwaite noted, many critics refused to see this African presence, in part because they still interpreted the value of Caribbean literature and culture in relation to European aesthetic standards. To counter this, he wrote, we must “redefine” the word “culture,” so that the Caribbean is not solely judged on its “Europeanity.” “Likewise,” he continued, “the African presence in Caribbean literature cannot be fully or easily perceived until we redefine the term ‘literature’ to include the nonscribal material of the folk/oral tradition, which, on examination, turns out to have a much longer history than our scribal tradition.” For Brathwaite, who died earlier this month, the key to understanding the Caribbean was to accept and study its orality: the way people spoke among themselves, local music, non-Christian religious rituals.

Rather than being ashamed of this oral tradition, which was an all-too-common reason for critics to eschew the Africanity in our contemporary Caribbean cultures, Brathwaite argued that we should embrace it, refusing to blindly follow the traditions of the European colonizers. In the wake of his death, I found myself thinking again of that essay, which I had first read in graduate school. And then I recalled, with a start, another memory related to Brathwaite, orality, and embarrassment, a moment I had pushed down into the dim place of the self where we hope things will disappear, like lost dreams. But, of course, the memory was still there, sepia at the edges with shame, and, like a gust of wind, Brathwaite’s death had pulled it back up.

I was in graduate school in Florida, in a small, largely white class that was discussing Brathwaite’s distinctive use of language, particularly in relation to his famous comment that he had been deeply influenced by T.S. Eliot—less by Eliot’s poetry than by the idiosyncratic rhythm Eliot used when reading his poetry aloud. We were examining “The Dust,” my favorite of Brathwaite’s poems, which is rendered entirely in vernacular dialogue. I decided to offer to read it aloud, since I was the only student from the Caribbean in the classroom. Because of the anxiety I had carried around with me for most of my life, I rarely volunteered to read anything out loud. But I had enjoyed “The Dust” so much that I decided to push past my trepidation.

The poem, which is presented as a series of unmarked conversations between people talking about the darkening state of affairs in their life—“de pestilence” ruining crops, the seemingly biblical omen in a volcano’s smoke—is a simple yet captivating evocation of what Brathwaite called “nation language.” Brathwaite developed the term as an expansive alternative to the more commonly used “dialect,” which, he noted, carried a “pejorative” connotation. In a 1976 lecture, which was later revised as a 1984 essay in The History of the Voice, Brathwaite famously defined nation language in contrast to the Eurocentric imagery that colonization had imposed upon our nations in the Caribbean. Many of us, he noted, had been raised so wholly on European history, languages, and art that we knew more about English kings than about our own islands’ heroes—like Nanny of the Maroons, who led an army of escaped slaves and free-born blacks against the British in Jamaica. We learned to write of snow and that distant Mother Country’s kingdoms, but lacked the language for our own world, for the hurricanes with their blind cyclopean rage and the dinghies rotting away in their sleep on our beaches and the beautiful madness of rum shops.

To capture those—the things we actually lived with—we needed to use nation language. “Nation language,” Brathwaite wrote, “is the language which is influenced very strongly by the African model, the African aspect of our New World/Caribbean heritage. English it may be in terms of some of its lexical features. But in its contours, its rhythm and timbre, its sound explosions, it is not English.” Nation language might occasionally resemble standard English, but it is utterly unlike the English that our colonizers employed; instead, Brathwaite wrote, “it is in an English which is like a howl, or a shout or a machine-gun or the wind or a wave.” It appears from the start of “The Dust,” which begins with a conversation rendered in the way I spoke back home:

Advertisement

Evenin’ Miss

Evvy, Miss

Maisie, Miss

Maud. Olive,how you? How

you, Eveie, chile?

You tek dat Miraculous Bush

fuh de trouble you tell me about?

As I read “The Dust” aloud, I imagined speaking to my friends back home, embodying the conversations Brathwaite conjures up. It was the kind of piece that, as Brathwaite knew, is meant to be read aloud, so you can hear those howls and winds and waves. The rhythm of the words felt smooth, easy, natural. I found myself even more bewitched by the poem’s colloquial melodies as I read. The one other student of color, who also had some Caribbean heritage, smiled and quietly hummed as the rhythms passed over her, because she, too, could hear that transatlantic music, those songs stretching from Senegal to St. Lucia.

But when I looked up at the end, I saw a white male student—an older, published writer who dominated all of our conversations—staring at me with a mocking, wide-eyed grin. He started laughing. I should read all of the poems from now on, he said. He declared that Brathwaite had either been uneducated when he composed “The Dust,” or that he had to be making fun of the people in the poem. What had felt natural to me, I realized, was foreign and farcical to him. I began to feel as if I had put on a kind of vaudevillian comedy routine in the student’s mind, if not a peculiar classroom minstrelsy. A few other white American students were smiling, while the others seemed unable to decide what expressions to wear.

I felt angry, but also ashamed. I knew, immediately, that he saw me and the poem—and, by extension, the poet—as inferior. He had implied as much in an earlier conversation about the Nigerian novelist Amos Tutuola, when he suggested that the reason Tutuola had written his first novel, The Palm-Wine Drinkard (1952), in vernacular was because Tutuola “didn’t know enough English” to compose it otherwise. (Tutuola’s book was the first African novel to be published in English outside of Africa, but, rather than considering the intention behind Tutuola’s linguistic choices, many white critics at the time, in language either subtly or overtly racist, argued that Tutuola was insufficiently educated; as Dylan Thomas put it, the Nigerian author knew only a “young English.”) Vernacular, in the student’s mind, was not a language but a stepping-stone, a failure to be a “mature” artist.

Between Europe and America, Charles de Gaulle is said to have declared upon his arrival in Martinique, there is nothing but specks of dust. Whether or not the tale is true, the fact that it could be true is telling: that for de Gaulle and my classmate alike, the Caribbean nations were little more than the dust of Brathwaite’s poem. The student had come into the class presuming that authors from our small islands were of less importance than the great “civilized” writers in our course, like T.S. Eliot—and Brathwaite’s nation language had only further convinced him of this.

I knew I shouldn’t take his mocking to heart, but I did. When you live in one of those dust-speck islands, it can be difficult to feel that your world “matters” on the stage of the world in the same way that large, powerful countries do, and one of my goals in taking the course had been to hopefully see precisely the opposite demonstrated: that the poets of my region were no less worthy of serious scholarly discussion and interest than the canonical giants of Europe and America. But the student’s response hit me hard. I fell silent, as I often had through my life, and retreated into the little nautilus shell of my introversion. I felt ashamed, both for how I spoke and then for my embarrassment, and I hated it. I still had not learned to accept myself, to accept the language of our canes and stoops and sea; instead, I let myself feel diminished by someone who knew nothing of my world.

Later, the incident in the classroom reminded me of an extraordinary scene from Is Just a Movie, Earl Lovelace’s satirical 2011 novel, which speaks to some of the same anti-colonial concerns as Brathwaite’s poems. In it, the narrator, a Trinidadian calypsonian named Kangkala, is initially excited when he hears that an American director has come to his island and sent out a call for local talent; and, for his audition, Kangkala proudly performs one of his songs, which he declares is a “poem.” But when Kangkala realizes that his entire role consists of dressing in a grass skirt and being shot, along with the other black actors, by the film’s white heroes, he revolts, indignant at the idea that he is meant to be nothing more than a nameless, faceless black prop in a white foreigner’s film. When he is “shot” on set, he refuses to lie down and die like most of the other local actors, who justify the indignity by saying, like the director, that “it is just a movie.”

Advertisement

Lovelace’s narrator clings to something deeper. He is not merely a body; he is a country, a principle of self-respect. “Either I’m nobody, or I’m a nation,” Derek Walcott writes in his grand poem The Schooner Flight, in a fiery statement that could have as easily come from Kangkala. What animates Walcott’s sentiment is the same élan vital of Lovelace’s scene: the choice one must make between being a nondescript corpse in a star-studded film, or standing up for the dignity not just of oneself but of one’s country. The moment in the novel is both tiny and triumphant, a rejection of the old colonizing order. I returned to reading Brathwaite’s work in The Arrivants and Ancestors, searching for the same subversive fire that made Kangkala, like Brathwaite himself, refuse to lie down and be tamed into an old, demeaning role.

*

From the time I was young in Dominica, I saw that shame was an anchor all too many of us dragged behind us. Some people, to be sure, were proud of the island, working tirelessly to improve it and to show the riches—both artistic and natural—we already had. Yet so often I remember hearing a casual refrain that America, and to a lesser extent England, were the places we should leave for when we were old enough, that the future was elsewhere. On trips with my family to the United States, almost no American we ever spoke with had heard of Dominica; at best, they assumed it was the same as the Dominican Republic, though they often did not know where that country was, either. We casually internalized this idea of invisibility as a nation, this idea that we were unimportant and infinitesimal in the grand scheme of things. To gain any shred of recognition and respect, the thinking went, we had to go abroad and present ourselves in a “civilized” manner, speaking not with nation language but something closer to BBC English.

And even speaking nation language among ourselves was an idea that occasionally sparked fiery debate. When someone argued that we should teach Creole in school and speak it in the government, affronted Dominicans would lash out: How, people demanded, will it help us get jobs abroad if we converse like uneducated fools? How humiliating would it be if the prime minister gave a speech in that kind of language? Who would respect us if our leader can’t even speak proper English? My mother, obsessed in the way of old colonial subjects with the idea of propriety, chided me frequently for speaking our vernacular; I was to use the Queen’s English, she said, or no one would take me seriously, no one would hire me, no one would take a look at me abroad.

Perhaps channeling de Gaulle, the Trinidadian writer V.S. Naipaul was notorious for belittling the Caribbean, unable to escape his own self-loathing about being from an entire region he viewed as culturally inferior to England. He frequently berated his fellow Trinidadians, for instance, calling them “monkeys” and other epithets. In his 1962 book The Middle Passage, he declared that the Caribbean simply had no history to speak of: “History is built around achievement and creation, and nothing was created in the West Indies.” If any prominent West Indian bore the anchor of shame, it was Naipaul.

Brathwaite, however, threw off this burden. Born in Barbados in 1930 and educated both at home and in the UK, Brathwaite argued that, from a young age, he had been primed to become an “Afro-Saxon”—a black Anglophile schooled more in English history than his own. After completing his studies in Britain, he relocated to Ghana in 1955 to work as a colonial education officer, where he found, to his pleasant surprise, a world much more aligned with his sense of self. There, for the first time, he felt a kind of cultural kinship that forever altered his aesthetics, showing him the deep connections that existed between Africanness and Caribbeanness. He soon rejected iambic pentameter as an “English” meter unable to capture the rhythms of our islands; in its place, he explored the “African” rhythms in the dancing and singing of the Afro-Caribbean religious practice of kumina; and in the particular stresses on words in kaiso, as in the songs of the calypsonian Mighty Sparrow. In 1970, in Jamaica, Brathwaite founded Savacou: A Journal of the Caribbean Artists Movement, which sought to publish new, radical Caribbean writing.

Because Brathwaite believed in nation language, it was inevitable that Savacou would feature it, and this—particularly in Savacou 3/4, a provocative 1971 double issue dedicated wholly to nation language—instigated an explosive debate in the region’s literary community. While some writers defended Brathwaite’s decision to privilege nation language, a number of critics blasted Brathwaite in print, arguing that he was only contributing to shameful stereotypes of the illiteracy and stupidity of Caribbean people.

Perhaps the most virulent of these critics was the Tobago-born poet Eric Roach, who declared, in an article containing a series of charged metaphors, that English literature, not nation language, was the only path to civilized, progressive writing. His stance was clear from his article’s title, “Tribe Boys vs. Afro-Saxons,” which deployed an image of “tribal” people—by implication, African-descended—as civilization’s antithesis, echoing the fraught sort of language that white American critics had used to condemn the rise of jazz in the United States decades earlier. “Are we going to tie the drum of Africa to our nails,” Roach asked in a representative passage, “and bay like mad dogs at the Nordic world to which our geography and history tie us?” After all, he continued in a sentence that appears to contain a remarkable apology for colonialism, “we have been given the European languages and forms of culture—culture in the traditional aesthetic sense, meaning the best that has been thought, said, and done.” Unsurprisingly, Roach quickly became a symbol of reactionary poetics, while his supporters quoted his article. Savacou and Roach’s rabid response had helped push Caribbean artists into making a decision: to embrace Brathwaite’s anti-colonial vision, or to continue emulating English literature. Although this tension had always existed in Caribbean writing, Brathwaite’s challenge to writers to use nation language shifted the course of our literature forever.

Despite the schism that Brathwaite’s work helped expose, Brathwaite himself encouraged Caribbean writers to form communities and stay in touch. When Roach, who suffered from depression, committed suicide in 1974, Brathwaite wrote a celebration of his writing as a “splendid” contribution to the history of Caribbean literature. Brathwaite wanted writers in the region and its diaspora to remain in touch, encouraging, for instance, the poet and scholar John Robert Lee to put together an email list of Caribbean writers that continues to this day as a way to share writing, news, and more. Some of his attempts failed, like his goal of creating what the St. Lucian poet Vladimir Lucien describes as a “Caribbean Library of Alexandria” in his home in Irish Town, Jamaica. Brathwaite had kept an extraordinary archive of work from the region, including early drafts of literary works, recordings of broadcasts, interviews, and more; tragically, the library was destroyed by Hurricane Gilbert in 1988. He may have lost his archive to that most Caribbean of forces, a tempest, but what matters more than what was lost, perhaps, is the deep love for our islands that moved him to create an archive in the first place.

And the archive’s existence, though brief, partly symbolizes why Brathwaite’s influence has been so enduring: his dedication to preserving and being a direct part of Caribbean literary culture. In the late 1960s and 1970s, for instance, Brathwaite would frequently visit the University of the West Indies campus in Barbados, where he would read his poems to rooms filled with the very people he wrote about. Both his verse and his delivery resonated with many there, including Lee, who told Lucien he was “exposed to Brathwaite’s distinctive and fine reading, which influenced my own reading later.” Indeed, Lee observes, every Caribbean writer since Brathwaite likely bears some of his influence:

Certainly, the comfort with and absorption of and unapologetic use of our “nation language” by the generations following Kamau reflect his deep and seminal influence. So unless one did some very close study, there is no major writer since Kamau who does not reflect, directly or indirectly, his mentorship.

That mentorship emerges from how daring Brathwaite’s poems were, employing not only nation language but also novel structures—“I Was Wash-Way in Blood,” for instance, is presented as if it is a newspaper article—and fonts influenced by computer games. This latter mode Brathwaite famously termed “Sycorax video style,” a name that captures the peculiar juxtapositions of Caribbeanness so well: on the one hand, there is Caliban’s mother in The Tempest—casually denigrated by Shakespeare as a “foul” and “damn’d witch,” rehabilitated by Brathwaite into a kind of animating spirit, a non-European muse. She was, he wrote in ConVERSations with Nathaniel Mackey, “the lwa who, in fact, allows me the space and longitude—groundation and inspiration… that I’m at the moment permitted.” On the other hand, “video style,” a term that evokes Brathwaite’s desire to make his poetry live on the page—as in projects like X/Self—as if it were multimedia.

Today, some of these Sycorax video-style poems can seem dated, with their arcade-game fonts and in-your-face spoken-word-poetry wordplay, and Brathwaite’s anticolonial message also feels like a product of a previous generation, a generation that had to fight for and through independence. Yet his oeuvre is so vast and extraordinarily varied that it is impossible to sum up Brathwaite by any one of his styles, and his poems still feel subversive to me, still feel essential if one is to understand Caribbean literature.

I think of “The Emigrants,” the only poem of Brathwaite’s I was taught in secondary school (where, perhaps tellingly, we read very little of our region’s literature), which describes the complexity of leaving the Caribbean. Brathwaite conjures up a series of emigrants, waiting to leave their islands for countries that, ironically, do not want them. The emigrants dream of a golden welcome; in reality, they will be turned away from jobs, denied housing:

What Cathay shores

for them are gleaming golden

what magic keys they carry to unlock

what gold endragoned doors?But now the claws are iron: mouldy

dredges do not care what we discover here:

the Mississippi mud is sticky:men die there

and bouquets of stench lie

all night long along the river bank.

Much like Samuel Selvon’s novel The Lonely Londoners (1956), the poem evokes the bleak, Eliotic wasteland that awaited Caribbean emigrants, particularly those heading to London—the so-called Windrush generation, named for the ship many of them had sailed on in the middle of the century—who would be turned away from the jobs and homes they had imagined were awaiting them in the Mother Country.

Yet Brathwaite’s poem still resonates today, particularly in the wake of the recent Windrush scandal, in which a large number of people from that generation were harassed over their immigration status decades after the fact, and some were even deported from the UK. The scandal was the result of the appositely named “hostile environment” policy, which sought, as then Prime Minister Theresa May put it bluntly in 2012, to “create, here in Britain, a really hostile environment for illegal immigrants.” Even though the Windrush generation had come to Great Britain legally, as subjects of the British Empire, the Mother Country still, apparently, didn’t want them in it—a sentiment that would have hardly surprised Brathwaite, who knew better than to expect much from the country that had treated its West-Indian citizens so callously when they arrived. Even now, England seemed determined, once more, to make us feel the drag of that old shame.

*

Like the crop-culling pestilence in the “The Dust,” shame will destroy us, eventually, if we let it linger too long. After the incident in class, I told myself to never to let what had happened in that classroom occur again; like Kangkala in Lovelace’s novel, I would stand up and speak in the face of indignity. So I did. Some days later, I told the student off in class. The nation language in Brathwaite’s poem, I said, was no less worthy of respect than Eliot—and why did he lionize Eliot’s Waste Land, which used a variety of languages and voices in dialogue, but dismiss “The Dust” for its own linguistic complexities? Why, I asked, did he assume that nation language verse was lesser by definition, if not for racial reasons? The student never really answered me; he retreated, instead, into the kneejerk defense for white Americans who have had their prejudice pointed out to them, rejecting the notion that he was a racist. The teacher redirected the conversation, but I knew I had gotten to him, if only for a moment. Whether or not I had changed his mind in the long term mattered less to me than the fact that I had defended myself, finally.

Shame, to be sure, is difficult to unlearn; when you are so accustomed to the weight of its anchor, the clang of its rusted chains, it feels strangely light to walk without it. Yet Brathwaite’s poems continue to be a paean to the power of rejecting colonially imposed shame. Brathwaite showed me a new, richer path to self-respect, aiding me in acknowledging the sea-crossing language that ties Africa to the Caribbean shores I grew up on, and, through this, he helped me remember how I love my old home when I needed to rediscover that love the most.