LAGOS—Around the time I decided to take writing seriously, my family moved to a new town. Before that, I had spent my school holidays away from home, in houses where the books seemed orphaned and unattended to. I remember filching a worn copy of People of the City from a bookshelf, beginning to read it: maybe it could teach me a thing or two about how to write a novel. And since I was only fifteen, I saw no error in lifting entire paragraphs of Cyprian Ekwensi’s story and, after changing the characters’ names, putting them into mine.

I was anything but subtle. I described a man who, like Ekwensi’s Amusa Sango, “was seeing a new city—something with a feeling.” And then I continued echoing Ekwensi directly: “The madness communicated itself to him, and in the heat of the moment he forgot his worldly inadequacies and threw himself with fervour into the spirit of the moment.” I felt pricked in my conscience, but I figured that my plot was so different from his, and that, being so far apart from him in age and renown, my sin was sure to go unnoticed.

Ekwensi, born in 1921, was one of the first Nigerian writers to publish a novel in English. He was prolific, and by the time of his death, in 2007, his output totaled nearly forty novels, along with short-story collections, children’s books, and film scripts. People of the City, which came out in 1954, predated Chinua Achebe’s better-known Things Fall Apart by four years and was preceded in Britain only by Amos Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard. That no one speaks of Ekwensi as the father of Nigerian literature is perhaps due to the undisguisedly didactic and moralizing character of the stories he told.

The clash between tradition and modernity was the central concern of the writers of Ekwensi’s generation; his eyes, by contrast, were firmly fixed on the emerging Nigerian middle class—its angsts and lusts and stereotypes—and his work gained a wide readership. In Jagua Nana, for instance, published in 1961 (and which won the Dag Hammarskjöld Prize), the lead character is a sex worker. Outraged by the sexually explicit language in the novel, the Catholic and Anglican churches in Nigeria vehemently disparaged the book, and it was banned in schools. People of the City had already introduced the themes and setting he would return to throughout his career: the city as a “hill” of wrongdoing, where “everyone mounts his own and descries that of another.”

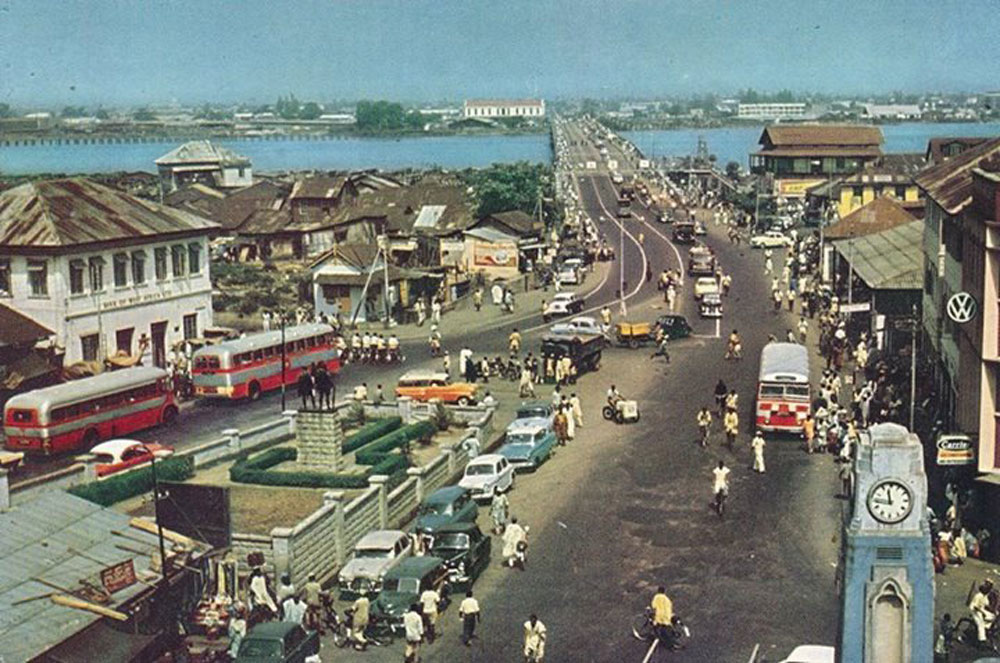

People of the City is set in the late 1940s to early 1950s, in an unnamed city, at a time when West African countries were clamoring for self-government and independence from Britain. The colonial officers began to relinquish control to indigenous civil servants, politicians, newspaper editors, and detectives. Connections between Nigeria and Britain remained close—Nigerians didn’t require visas to travel to Britain. In 1951, Ekwensi won a scholarship to study pharmacy at London University. While on the ship to England, he began work on People of the City. Written by a young man en route to the center of the British Empire, the book reflects his impatience with colonial dithering: the people of West Africa now had sufficient wisdom to govern their cities; it was time for the British to go.

Any Nigerian writer who has tried to write about Lagos as a city with feeling descends from Ekwensi. Starting in 2005, with Sefi Atta’s Everything Good Will Come, the last decades have seen that cohort grow in number. Atta’s feminist novel covered 1971 to 1995, years of military dictatorship, a time when it was nearly impossible to keep family life and politics apart. In contrast, Teju Cole’s Every Day Is for the Thief, set sometime around the mid-2000s, after the country’s return to democracy, is the introspective account of a Nigerian who has been abroad coming back to the city where he once lived. And the 2018 collection Lagos Noir, includes thirteen stories that, as editor Chris Abani writes in his introduction, capture “the essence of noir, the unsettled darkness that continues to lurk in the city’s streets, alleys, and waterways.”

Amusa Sango’s city is surely dark and unsettling. He is a crime reporter for the West African Sensation, and he knows, we are told, the “smell of news.” In one instance, it is the story of a woman and her child killed by men to whom she’d lent her husband’s gramophone. In another, it is a ritual murder of a man by a society that he’d joined to better his fortunes, and whom they kill after he refuses to turn over his firstborn son. Amusa can sniff out the news because he knows the city he lives in, its drive to make good, and the dangers that lie in the way. “What is the secret of getting ahead in the city?” he asks.

Advertisement

Later, at his first meeting with Beatrice the Second, the woman he’ll eventually marry, Amusa says, “The city is overcrowded, and I’m one of the people overcrowding it… If I had your idea, I would leave the city; but it holds me. I’m only a musician, and a bad one at that. A hack writer, smearing the pages of the Sensation with blood and grime.”

He realizes, like many city dwellers, that year by year it becomes more difficult to disentangle his idea of fortune from the city’s promise, one that may well prove to be illusory or instead bring misfortune. Amusa makes strategic alliances and finds the door shut in his face as a consequence, or he succumbs to his naïveté: he is evicted from his house after his friend raises an uproar there; when he writes a story favoring that same friend, he finds himself fired.

But Ekwensi also builds Amusa up. Well-known as a crime reporter and the leader of a highlife band—“a most colourful and eligible young bachelor”—most girls in the city have his address. Although he is a catch, he is engaged to be married to Elina, who is in a convent, but from the start of the novel he is pursued by Aina, whom he sleeps with and feels conflicted about but refuses to make happy. His marriage to Beatrice receives the reluctant blessing of her father.

Unemployment, homelessness, women who wear “loose, revealing trifles, clinging to the body curves so intimately that the nipples of the breasts showed through”—Amusa must struggle with all these. That the arc of a man’s life tends toward marriage, that his prestige is underscored by the match he makes, is as prominent a theme in the novel as the vagaries of the city. The people of the city are sexual beings, men and women all lusting after one another (even if Ekwensi’s women often seem more eagerly lascivious than their male partners).

For twenty-six-year-old Amusa, the story ends with the prospect of happiness. His bride says to him, “Amusa, let’s snatch happiness from life now—now, when we’re both young and need each other.” Nothing is said about work and getting back on his feet. What matters is his youth, and the triumph of love.

By 2100, Lagos is estimated to become the largest megacity in the world, with eighty million inhabitants. There is a jostle—in academia, policymaking, speculative fiction, futurist studies—to propose what kind of city it will become. Are there hints to be taken from Ekwensi? If the Lagos that inspired his writing in the late 1940s was already overcrowded and subject to the sorts of clichés that remain current, how about the Lagos of 2100? What the city demands most, as an antidote to failure and a prerequisite for survival, is wariness.

When I lived in Lagos, as a teenager with my family and as an adult making a life on my own terms, the size of the place made it cheerless. The scale of desperation unfolding in front of me made me anxious; I had a hunch that many people, including my friends and family, might not realize their dreams of a better life. Yet, though many Lagosians pray for a miracle or breakthrough in their businesses, they also rely on something other than the supernatural: they are streetwise; they know an opportunity when they see one.

In Lagos, a story is told about a teenage boy who picks up a stray naira bill, an insubstantial sum, and there and then he turns into a yam. People who saw this transformation gather around, distressed. They agree to wait for someone to pick up the yam. A man with a limp shows up, slices off a chunk, and blood spurts out. Then, for several minutes, he chants unintelligible words. Right before the eyes of the agitated crowd, the yam reverts to a boy with a bloodied right ear. In another version of the story, the teenage boy pisses on the bill before picking it up. He stays human and proceeds on his way, eager to spend the money.

In People of the City, the city remains nameless, even though numerous clues—the use of Yoruba in conversations, a rendezvous by the lagoon—point to Lagos as the archetypal West African city where the story of Amusa’s coming-of-age takes place. The atmosphere is noir, and everywhere vice is interleaved with virtue.

Adapted from Emmanuel Iduma’s introduction to People of the City, which will be published by New York Review Books Classics on June 9. Iduma will be in conversation on Zoom with NYRB Classics Editor Edwin Frank, also on June 9, at 6 PM.

Advertisement