He was born John Robert Lewis in a wooden house that had no electricity in Troy, Alabama. He had ten siblings, including a brother who was born deaf. His mother called him Robert. As a child he played and ran through the 120 acres his father owned with twenty siblings and cousins. He loved the life of his childhood. Something made him different.

At fifteen he wrote a letter to Dr. King saying he wanted to integrate the high school in Troy. Dr. King called him “the boy from Troy.” Washing dishes at American Baptist Seminary in Nashville, he studied nonviolence, the way of Gandhi and Thoreau with Reverend James Lawson. By 1963 he had been arrested forty times.

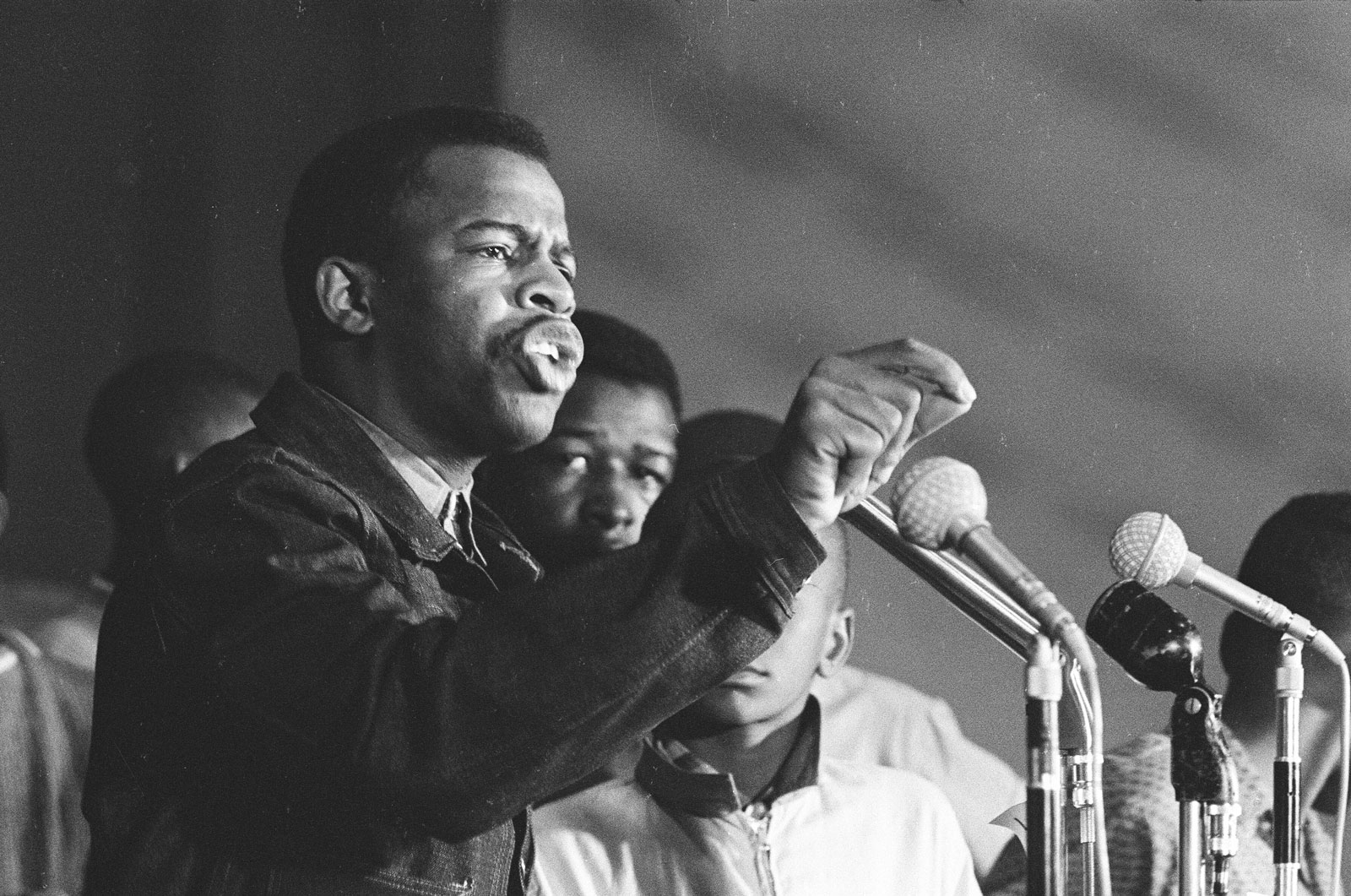

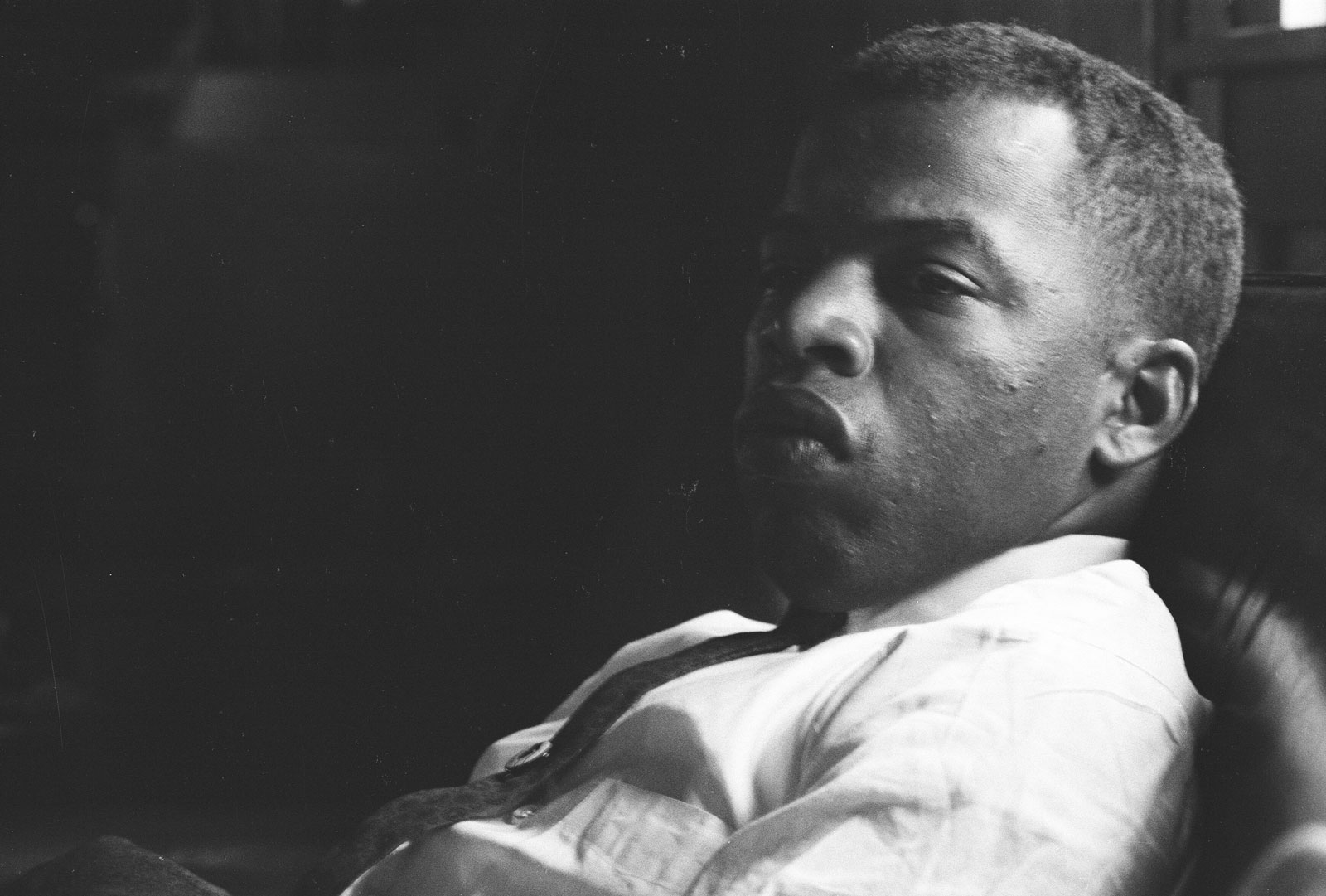

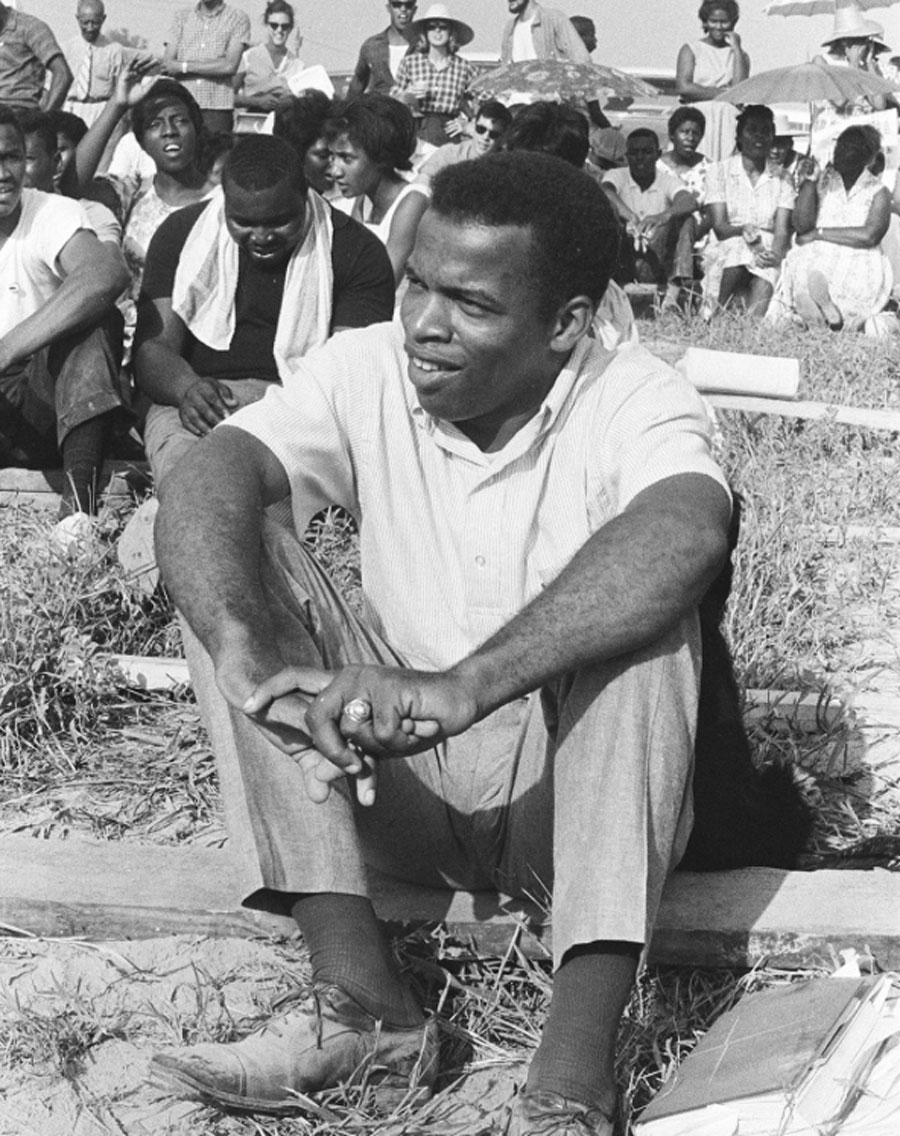

When, in the summer of 1962, I first saw him sitting in the corner of a small church in Cairo, Illinois, I knew who he was. John Lewis was a Freedom Rider. I gazed at him with wonder on that morning in southern Illinois. John was twenty-two years old. That summer he had asked the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) for ten dollars so he could work in Virginia, but for some reason Jim Forman had sent him to Cairo. I had never been in the South and I probably had never heard anyone from Alabama speak. Then, in that small church, he got up to speak. Though there might have been as few as fifteen people there, his voice exploded across the room with passion. I was transfixed. I would not leave the movement for another two years and in another sense I would never leave John.

In 1963 I moved to Atlanta to work full time for SNCC. John had a small apartment in West Atlanta and asked me to move in with him. Our third roommate was Sam Shirah, a white student organizer, who was also from Troy. Growing up in Troy, John seldom saw a white person. His mother wouldn’t let him buy ice cream at the drugstore because they made the “colored” children sit outside on a bench. Last year my wife, Nancy, and I ate lunch with John in that drugstore. Everyone wanted to shake his hand. Now Troy celebrates a “John Lewis Day.” Both Sam’s great-grandfathers fought for the Confederacy. John’s were slaves.

John had a quiet, naive side. It was easy to underestimate him, and throughout his life many people did. That is because in many ways he never changed from what he was—a farm boy from Alabama. In 1997 I had a show in Atlanta and John came to visit. I was very excited that he was coming to the opening. I stepped outside the building to greet him. He was sitting in the driver’s seat of a car. “Notice something?” said John. “No,” I answered, standing by the window. “I’m driving,” he said. John was fifty-seven and had just learned to drive.

In late January, when I learned of John’s diagnosis, I flew to Washington to stay with him in his home. By then he was mortally ill, and we knew we might never see each other again. He lay in bed with a large picture of his mother by his bedside. I stayed upstairs in a guest room. Fifty-seven years earlier we had been roommates. We were roommates again. Each morning I made tea in the basement, then carried it upstairs to sit by his side.

A few weeks ago he said on the phone, “I am going back to Atlanta.” John said they had stopped the treatment. It was no longer doing any good. John wanted to be home with the things he had collected with Lillian. In the very corner of his bed where he slept and would die were a group of SNCC posters and photographs. Every one of them was made by me. In the open attached garage were John’s cats and kittens. He fed them every day, just as he had fed chickens as a boy. When he returned to Atlanta, I asked him about the cats and he said, “I don’t think they recognized me.” His voice had changed. It was raspy. He sounded short. It wasn’t much of a conversation.

I had been filming John for years and I wanted so badly for him to see the finished film, the film I called SNCC. He might have watched ten minutes before he fell asleep. Then I called to say goodbye. He said “yes” a few times, he could hardly speak. I told him I was sure that I would see him again. That wasn’t exactly true, but I know John believed there was something after death. I had asked him how he felt about Julian Bond and Jim Forman and all the SNCC people who had died. “How does that make us feel, John?” I asked. “How does that make you feel?” and he said, “Do you remember Stanley Wise?” Sure, I said, we were with him in Cambridge. “Sometimes I feel I can pick up the phone and call him. But he is not there.” Now it’s John who is not there.

Advertisement

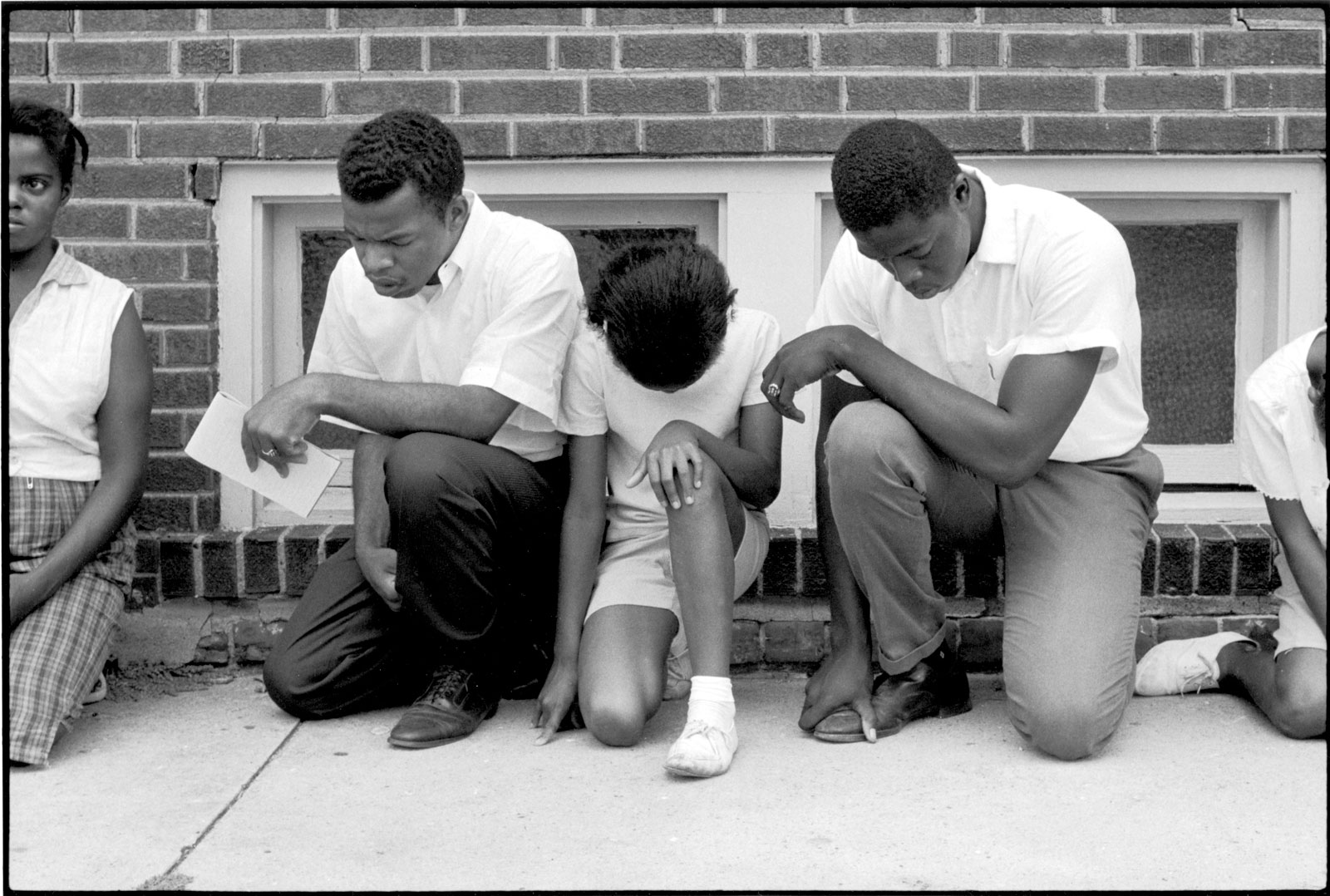

John Brown was held as a terrorist. When he was captured at Harper’s Ferry, all his abolitionist supporters fled or went into hiding. Thoreau alone saw John Brown as a saint. John Robert Lewis was an American saint. He took the blows for freedom upon his own body, and like Kafka’s Hunger Artist, became the physical embodiment of the movement. He believed so profoundly in the American ideals of equality that he repeatedly put himself in harm’s way to achieve these goals for everyone. As SNCC chairman he was the chosen symbol of the black uprising. SNCC was the point of the spear of the movement. Early in the Nashville sit-ins they locked the doors of a Woolworth, and when clouds appeared in the closed-up room John said, “They’re going to gas us.” At Rock Hill, South Carolina, a mob hit him in the head with a Coca-Cola crate. In Montgomery they beat him bloody as he tried to protect a white Freedom Rider whose teeth had been knocked out. His courage came from centuries of justice denied.

That last day I sat on his bed to film him, then rearranged his quilts as I got up to leave. Now he has left us. His soul will be with us forever.

Go to rest with the angels John, we will miss you.