Two recent archival projects documenting Black life in America coincided in 2014. First, the Museum of Modern Art premiered the restoration of the 1913 Lime Kiln Club Field Day, the oldest surviving feature with an all-Black cast. Second, the African American Home Movie Archive was created as a space to collect, digitize, and provide access to home movie collections from the 1920s to the 1980s. Archival preservation efforts have become increasingly attentive to visual materials that have been systematically discounted, with home movies in particular recognized as a unique repository of intimate histories. They are especially important as private records of Black life, as rare examples of Black people exerting agency over how they’re documented, free from the demands of mainstream film circuits that have been historically bound by capital and white supremacy.

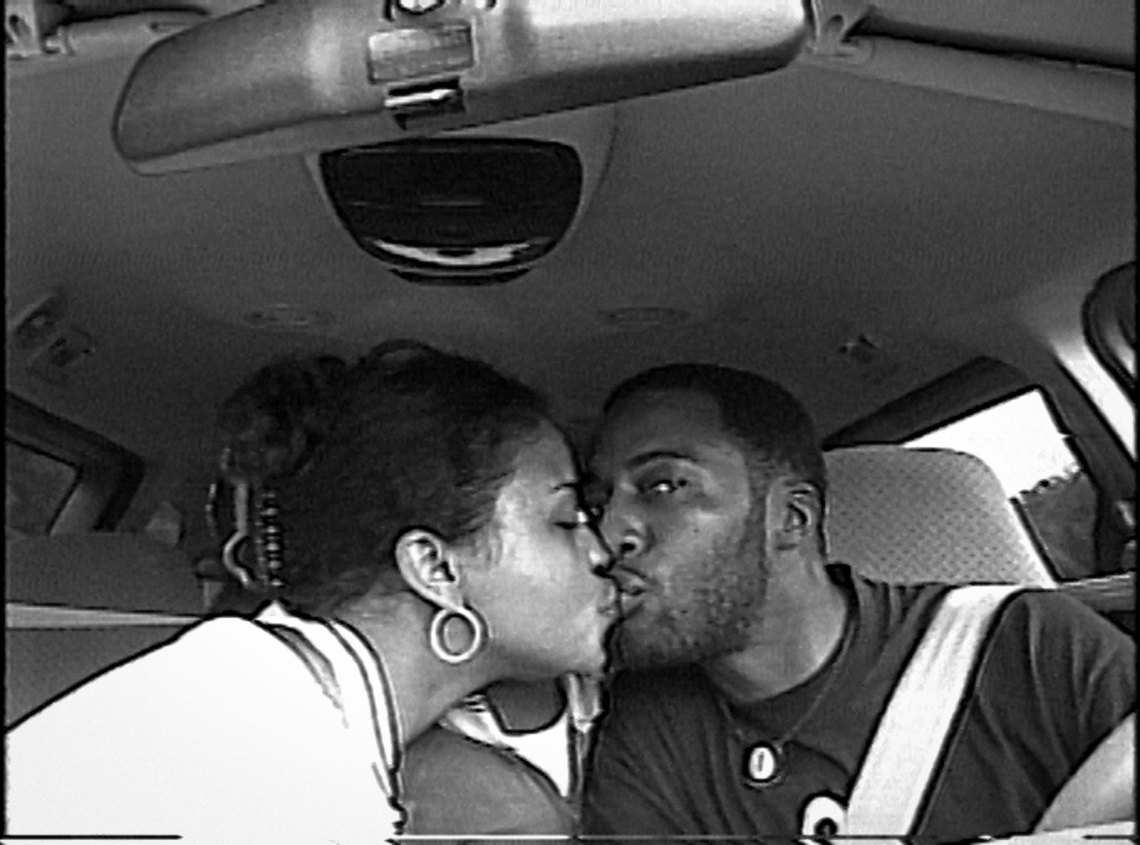

These two archival endeavors also form a point of convergence for the work of artist and filmmaker Garrett Bradley, whose Sundance-awarded documentary on the effects of the carceral system, Time, is now streaming on Amazon Prime. Her work America (2019) draws on footage from Lime Kiln Club Field Day to imaginatively supplement the archival losses of African American cinematic history with a hypnotic sequence of vignettes. Time is also a work about augmentation and loss, but on a more intimate scale: Bradley explores the irrecuperable cost of time stolen by incarceration from a family, and attempts recovery through storytelling, a collaboration between the director and the family’s home movie archive. The film centers on Fox Rich, who becomes a kind of co-director when she shares with Bradley eighteen years of home movies that she made during her husband Rob’s imprisonment, which Bradley weaves into her own footage. Time tells the story of the Richardsons and their six children, as well as their larger community, with an acute awareness of how one person’s incarceration suffuses the daily lives of so many more.

The film’s anchoring in the everyday counters familiar depictions of incarcerated people that foreground spectacle or reinforce non-belonging, the expulsion from social life; and Fox Rich’s resilience resists the exhausted trope that individual heroics are either a fair demand or a solution for dismantling systemic injustices. Time instead offers an urgent, expansive meditation on how survival is always collective, making visible what we sometimes are unable or unwilling to see. I spoke to Bradley recently about the release of Time, the need for collaboration, and the importance of honoring the small things we do every day. Our conversation has been edited and condensed.

Yasmina Price: Where are you existentially, emotionally, ideologically?

Garrett Bradley: For the past few weeks I’ve been talking about Time to support the release of the film. I’m simultaneously working through America, and its new iteration as an installation [at MoMA, Nov 21, 2020–Mar 21, 2021]. And so, it’s a lot of team-building and team-working, in a very different way from what filmmaking requires, which is always fun. So much of the work is about bringing the best out of people. Identifying what in their work world brings them joy and finding ways to make that an integral part of the process….something that then aids the larger goal.

[With the release of Time] I’ve been presented with a lot of questions, a lot of the same questions over and over again. And that becomes an interesting exercise, an opportunity to break outside of the question: What is the question actually questioning? That’s something I’ve been thinking a lot about—and I think it’s specific to Time—thinking about erasure, thinking about this current moment, where we have such an unprecedented amount of allyship in our movement toward racial equality in America, and a lot of that being inspired by technology and optics around things that have always been happening. When we consider the prison industrial complex, it only furthers this idea of erasure—that we have such little visual evidence of 2.3 million incarcerated Americans. So how do the questions being asked reveal expectations and possibilities for what can be done in this moment? How, as artists and filmmakers, can we think about our craft as a tool of proof? Maybe that’s what art is? Proof of something less obvious? Proof of things hidden, less considered?

That makes me think of an idea presented by abolitionists—that prisons are the creation and management of surplus populations that are excluded from social life. How have you been thinking about space and separation, and how can we build roads or bridges to overcome that? Whether it’s the fact of how carcerality works as separation, or the situation we’re in right now, where we can’t meet each other physically in the same ways?

Something we’ve been talking about a lot, in the context of both America and Time, is how can we not take for granted examples of resistance that exist in the everyday, and that are seemingly mundane? Like love. Like staying in touch with one another, unity, maintaining one’s individuality parallel to performance? How can we think about these practices as active forms of engagement with resistance? And I think that this year has helped to illuminate for everybody what many of us, historically speaking, have always experienced and known.

Advertisement

Collaboration is clearly so crucial to the way you work, but does that extend across time, in the sense of the lineage of filmmakers you’re working within? I see your work within a tradition of Black women filmmakers who have been attentive to the everyday in ways that show that there is radical or even revolutionary potential in the mundane. Are there filmmakers or cultural workers in other mediums who you’ve been thinking with?

It’s a challenging question because I have spent a lot of time and energy building and being a part of a community that is not inherently connected to my practice. It’s always been really important to me that I have a job that’s totally separate from filmmaking, that I have friends and family members and people whom I’m in dialogue with who come from all different types of ways of thinking and working and living in the world.

I can tell you that when I was growing up, when I was younger and in film school, and studying religion in college, I was looking at Billy Woodberry, Charles Burnett, Julie Dash, and John Cassavetes, who were hugely inspiring to me. I had an opportunity in high school to assist Linda Goode Bryant and Laura Poitras on their [2003] film Flag Wars. And have continued to be inspired by the work they have done separately as artists and activists—their ability to constantly evolve and respond to the needs of now. It wasn’t until I graduated from school that I learned about Madeline Anderson, Ngozi Onwurah, Fronza Woods…William Greaves, who completely shifted my entire perspective, and Wong Kar-wai, and a lot of [Andrei] Tarkovsky films and Neorealist films from Italy, all as reference points. I remember seeing Steve McQueen’s Hunger while I was an intern at the Telluride Film Festival…But I’m also really inspired by music, by Sonny Rollins and Art Blakey and John Coltrane and Alice Coltrane and Neil Young and Lil Wayne, and so many others that I’ve benefited from.

Black artists have historically and are presently facing and working against incredibly restrictive established narratives. I see your work as part of a project of resistant storytelling, of reinterpretation and reimagination.

This is a slight deviation, but I do think it’s connected and really interesting—that for both Time and Alone (2017) [a short film about her friend Aloné Watts, weighing the decision to marry boyfriend Desmond Watson, after his incarceration], when I had the privilege of being able to show the film to an audience and actually have an in-person Q&A, a lot of the questions were around the legibility of the crime itself; like, “Why didn’t you go into the crime? Why didn’t you focus in on the details of the crime?” And I think that for me, it was really important to talk about the effects [of incarceration] being just as important as the facts [of incarceration] themselves.

There are different ways to tackle the same issue. I don’t think there is one singular approach that is more valid than others. Time, for instance, stands on the shoulders of Ava [DuVernay]’s 13th, and I see them really working together. The facts and the effects need to work together. I also want the work to be nourishing, to be therapeutic, to be something that we ourselves could go to and knew was for us, in addition to being something that was maybe eye-opening for those who were not yet aware. And so, when we talk about the universality [of a story], who are we really talking about? There’re 2.3 million people incarcerated in the country right now, if not double, triple that number affected if you take into account family and loved ones. So this is a major experience in the country. Questions around universality, legibility are, to my mind, deeply coded.

Something else the film illuminates is how Black survival in the US has always depended on inventing forms of community, of having these sort of flexible kinships beyond the nuclear framework. Did the process of filming Time make you think of community differently or did it perhaps reinforce ways you already conceived of how we collectively support each other?

Advertisement

I think it really reinforced this idea of thinking about unity, and staying connected to the ones that we love as a form of resistance. That that is an inherently political act. The reason why I think that that’s so important is that, unless we’re out in the street protesting or involved in something more directly political, I think many of us might feel that we are disengaged from participating in an active movement. And that is further validated by the fact that to be Black in America is already an exhausting experience. In the process of making the film, it was a reminder, and hopefully a reminder to everybody who watches the film, that one is participating in a beautiful and active and critical way just by their maintenance of familial ties, the ties to those that you love, and by your ability to hold on to yourself as you see yourself.

Something I was thinking about, too, is how waiting is such a critical piece of all of this. Waiting as repetition and waiting as anticipation—and also as nostalgia. Fox has to occupy all of these different forms of waiting at once, and one scene that genuinely broke my heart was when she’s on the phone, and at first she’s sort of laughing it off that she’s once again not getting answers from the court clerk’s office about Rob’s release date, and then the scene builds into this emotional crescendo where, at the end of it, you see her facade crack a little: this brave face that she’s been putting on falls apart a bit.

I did feel as if we deserved—as Black women, as Black families—to have that moment of just being like, You know what, I am going to be angry. I am going to have that, that breath, and I am also going to show you that I can do that and still keep it moving, because that is what is required of me. That to not have it would have been also to potentially reinforce the sort of more externalized ideas of strength that are not sustainable or real.

Yeah, because there’s this myth of the strong, invincible Black woman, which ends up being an additional burden and an erasure of all sorts of different networks of care. How have you been sustaining yourself, personally—what has been giving you comfort?

Walking has always been an important of part of my life. And my relationships with my family and my friends, and cooking food. Those three things. I’m naturally a pretty quiet person, I’m naturally more introverted; I am more comfortable in a place of contemplation and listening and observing than I am of being the center of something. So I think a lot of what feeds me is finding spaces where I can be of service to others.