In September, the Whitney reopened “Mutualities,” the first New York solo show of multidisciplinary artist Cauleen Smith, with the addition of five of her “In the Wake” banners from the museum’s collection. These works—colorful, blood-spattered fabric updates on medieval-style heraldry—were originally included in the 2017 Whitney Biennial, and they now hang from the ceiling on the museum’s ground floor, newly powerful after a summer of protest signage.

Upstairs, two of Smith’s films are on view. Sojourner (2018) screens as disco balls, one spinning on a record turntable, throw light around the darkened room; the words of jazz legend Alice Coltrane serve as both soundtrack and prop, hand-sewn into the dayglo orange banners carried by a cast of women onscreen. Pilgrim (2017) also features Coltrane—this time, her Turiyasangitananda Vedantic Center in California—as well as nineteenth-century activist Rebecca Cox Jackson’s New York Shaker community. The third pilgrimage site is LA’s Watts Towers, a folk art sculpture and monument, which also appears in Sojourner—a landmark created by Italian immigrant Simon Rodia, which miraculously remained unharmed during the 1965 Watts Riots. These shared references spill over into Firespitters, a series of illustrations of books that hangs on nearby walls.

Smith, who trained as an experimental filmmaker, has long made work centered on exchange, borrowing from Afrofuturism and science fiction (the work of Octavia Butler, for example) to create imaginative utopias, built of reciprocity and care. The titles of Smith’s shows are often emblematic of this, like “We Already Have What We Need,” which was on view at Mass MoCA until March of this year. Smith, who is now teaching at CalArts, was recently awarded the Studio Museum’s Joyce Alexander Wein Artist Prize, created fifteen years ago by jazz impresario and musician George Wein to honor his late wife. I spoke to Smith about reading lists, collectivity, and making artwork for the future. Our conversation has been edited and condensed.

Stephanie LaCava: Your solo show “Mutualities” originally opened at the Whitney in February, only to close and reopen with the museum in September. How long was the show in the making? Did it change at all with the pause of the pandemic?

Cauleen Smith: I feel so fortunate that “Mutualities” was opened again. In addition to the show having an extended life, visitors are now greeted by even more of my work (the added banners). That is enormously gratifying. We did have to change some things to make it safer for visitors. In the main chamber of the exhibition, where Sojourner plays, we had designed a really fabulous twelve-foot-long lounger bench covered in blue shag carpet. We called it the Cookie Monster. I loved that thing and really felt that it was crucial to influencing the way one might experience Sojourner, because it was so clearly an invitation to stay and make oneself very comfortable. Covid-19 means we are not allowed to be comfortable in public space any more. And this greatly saddens me. It will have some pretty profound effects on future work.

You studied film and have worked as a director, screenwriter, cinematographer, and, at times, producer of your films—two of which, Pilgrim (2017) and Sojourner (2018), are showing at the Whitney. Who are the filmmakers who feel most vital to you now?

I’ll be honest, I do not pay much attention to narrative cinema anymore. I feel like it’s an ancient language, and twentieth-century art form. Much the way that theater was the dominant form of the nineteenth century. Film language has now become television serial drama language, and TikTok language and Instagram language, and, most importantly, video game language. The grammar and syntax have adapted to these ever-evolving platforms. So the gatekeeping, craft-oriented culture of cinema has dissolved. I’m quite happy to be free of auteurs—almost all of them male, most of them racist and/or misogynistic. I don’t miss much of that.

What was exciting about making the transition from the commercial film world to the conceptual art world was the way in which the tools of planning a production in film served me so well. I still apply the same craft; I just do it in several dimensions and media at once. But in my mind, all of the elements of my installations and all of the medias involved, from drawings to chairs to wallpapers to videos, are building one single experience: a conversation. Maybe it’s not a linear narrative anymore, but the world-building is still in play. I just use space more dynamically as a tool to move people.

I was taken with the styling of Sojourner: the colors and clothes of the women, the transistor radio props (I think of Jean Cocteau’s Orpheus). Did you have specific references in mind (I read about the Life magazine spread on Watts Towers.) For some reason, I keep coming back to the woman in the neon streetwear shirt.

Advertisement

Cocteau’s Orpheus is one of my favorite films and definitely a reason that radios pop up in my movies. Also, the radio is in direct conversation with Bill Ray’s photographs that he took at Watts Towers [for Life magazine]. I am interested in analog communications devices. In the same way that young people feel a sense of discovery on TikTok, I always felt [growing up] as though the radio was a portal to all manner of elsewheres. So I use it like a talisman in many of my works.

More importantly, the film features figures from Black spiritual and cultural history, and writings from women from different eras, including Rebecca Cox Johnson, Sojourner Truth, and the Combahee River Collective, as well as the music of Alice Coltrane. What does it mean to you to put these voices in conversation with one another?

Temporality and monumentality and mobility co-mingle in the imagination. Rebecca Cox Jackson, Alice Coltrane, and The Combahee River Collective ([the group’s name] a homage to Harriet Tubman), Noah Purifoy, and Simon Rodia all created space through their work and faith to enable others to actualize themselves. They created pathways toward liberation, autonomy, and self-determination. These figures embody models for radical generosity.

People tend to dismiss utopian experiments as failures because they inevitably end. My question is: Why do we think that forever equates with success? How do we measure success?

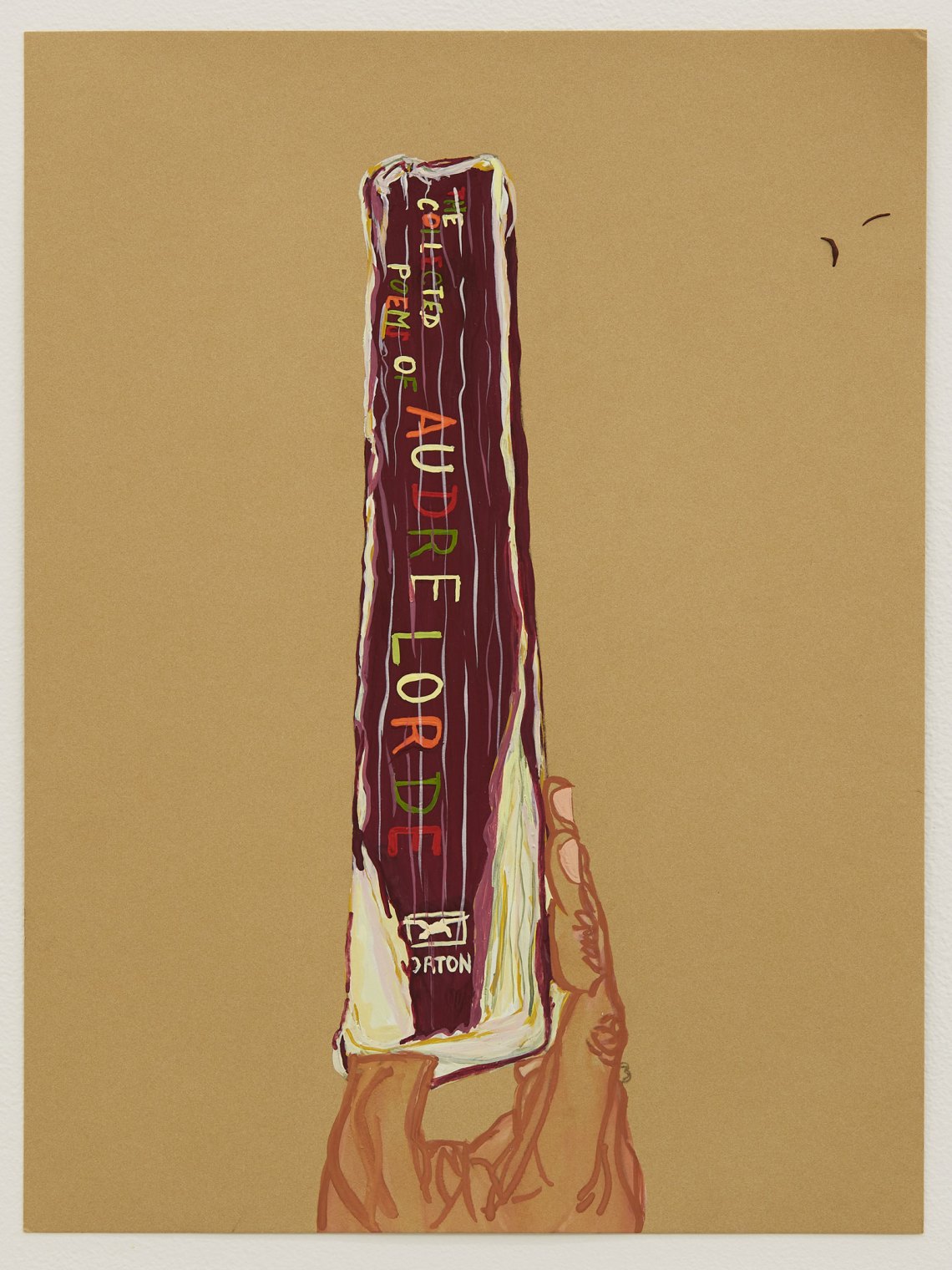

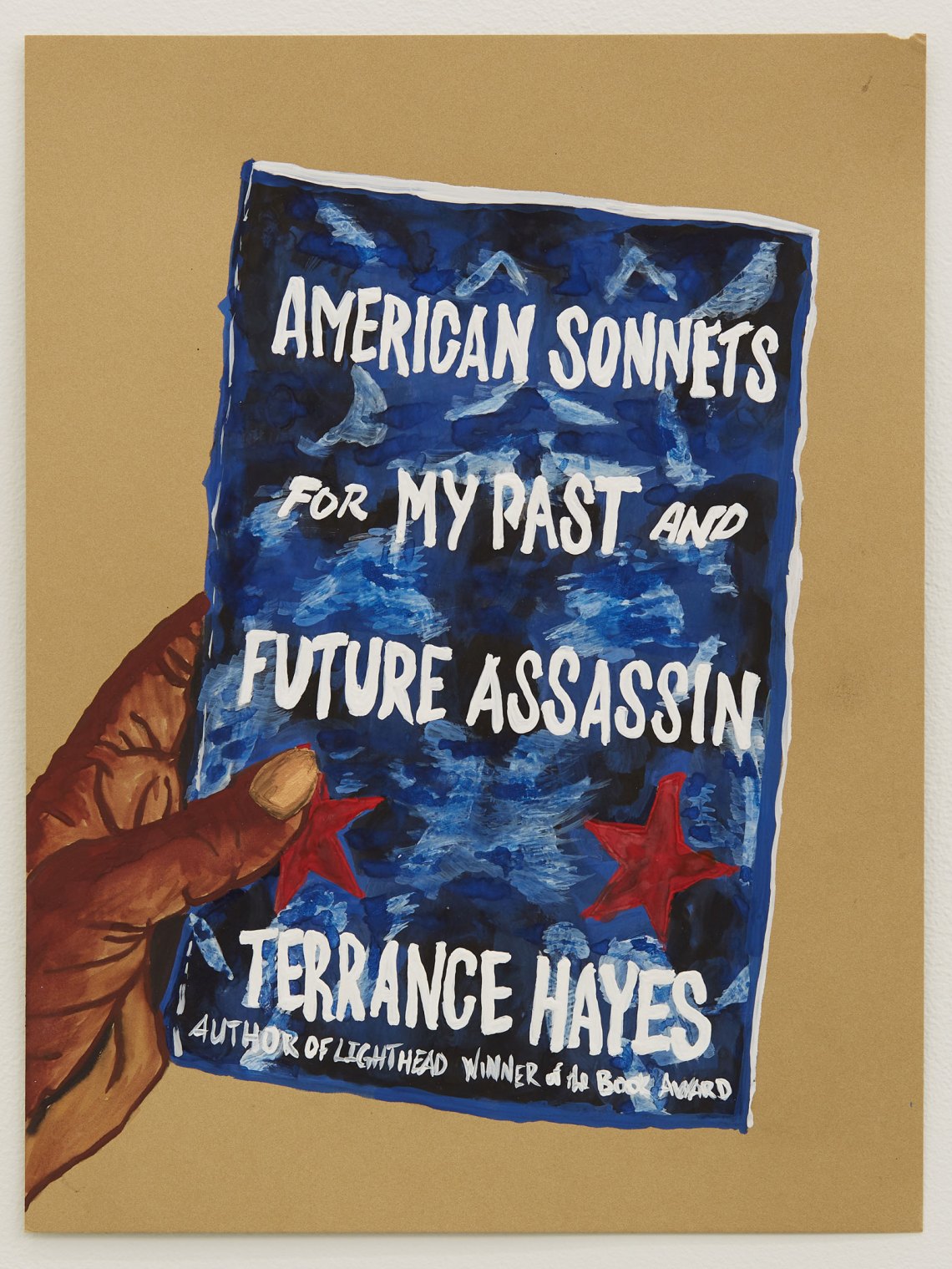

Part of your ongoing Firespitter series, illustrations of books and sometimes the hands that hold them, is on view. I loved, for example, the worn spine of The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde and I was reminded of all the times I’ve seen her work referenced in the past few months. I looked at your reading material works—also illustrations and paintings of lists and books—from as far back as 2015 (Human 3.0 Reading List 2015-2016) and then the more recent BLK FEMINIST Loaner Library, and many of those titles have recently been recommended in the reading lists that have circulated on social media since the summer’s uprisings, with people seeking knowledge of this country’s history of racism and inequality through study. The titles from these past works of yours have been assembled and can also be accessed through the Whitney’s library.

Could you elaborate on what you were thinking about in conceiving these alternative canons? What have you made of the recent practice of shared reading lists and free libraries?

I love reading lists because they reveal so much about the recommender, and they always provoke people into pointing out absences and oversights. A reading list is a provocation and an invitation for discourse. I think the reading lists that proliferated this summer were wonderful because they suggest that the work of developing consciousness and understanding our socio-political conditions is work that individuals must, to some extent, do for themselves.

The list operates in lieu of every Black person’s having to conduct very depleting and alienating personal tutorials with their white friends. Those days are over. Scholars have done the work. Ignorance is no excuse. Get an audio book. Subscribe to a podcast. Whatever! The information is out there, and all of these lists really demonstrate that the information has always been out there—along with the willful refusal of many to engage with it.

I’m curious, what have you been watching and reading during the pandemic? Are there any new voices you’ve discovered over the past few months that you could imagine placing in the canon of books you’ve created or putting into conversation in future films?

I am always just playing catch-up. The early weeks of the pandemic were wonderful in this respect at least: because no one was even communicating, so I could read with impunity! I didn’t feel the tug of social obligations or have to negotiate the interruptions of travel.

Now Zoom interrupts everything all the time. But for a couple of months, I was a reading fool. So I read Sara Ahmed, Kathryn Yusoff, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Glen Coulthard, Derek Jarman’s garden books, Imani Perry, [Fred] Moten, [W.E.B.] Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction in America. And some truly amazing Black speculative fiction from N.K. Jemisin, Nnedi Okorafor, and Tomi Adeyemi. I think a Black speculative fiction reading list is in order.

Advertisement

I’m doing some research for a new body of work, but it’s too early in the process to make any of it sound coherent. But wandering around with ideas is so much fun.

This summer, amid so much uncertainty, I found such inspiration in listening to Sun Ra. Would it be right to say that Afrofuturism is central to your work?

I’ve always loved science-fiction and discovered Octavia Butler quite accidentally and fortuitously just by browsing bookstore sci-fi sections. I think I found Dawn (1987) first. There was a crazy picture on the cover of a white woman with red hair strapped into a machine with tentacles. I cracked the book open and saw some names that looked Ghanaian, so I bought it and was hooked after that.

It wasn’t until I stumbled onto [writer] Mark Dery’s article [“Black to the Future,” in which he coins the term “Afrofuturism”] and got hip to [writer and musician] Greg Tate that it all started to click and I understood my interest in sci-fi as being directly linked to my interest in the experience of race and geography and history and memory. And then there was the afrofuturist.net website, where I would just read everybody’s conversations.

Before those encounters, I had been thinking of sci-fi as a shameful hobby, with people dismissing the entire genre, not a tool or a conceptual framework. Those New York intellectuals changed everything for me. For most folks, it’s easier to latch onto a single personality as opposed to the genre itself. But I find the structures and strategies of science fiction to be incredibly generative. Sci-fi takes what can be known about the present and past to imagine possible futures or parallel realities.

So the slogan “Make America Great Again” appears in Parable of the Talents because Butler was researching and writing during Ronald Reagan’s presidential campaign and that was his slogan. And here we are in 2020 and her book is even more chilling for its prescience. Sun Ra and Butler are models for me, but sci-fi itself is a formal structuring agent.

I love the way it seems your work is ultimately centered in optimism. Perhaps this relates to what you’ve said, in relation to Afrofuturism: “There’s gotta be something else, the after-the-trauma.” I wonder if you could speak to this—and also, to the idea of care and the collaborative nature of artistic production and community.

I think of it as pragmatism, really. I just need tools for how to proceed, for how to keep it moving. I sometimes need a reason for constructive moves that extend beyond my own conditions. So I like to create practices that push toward that extension. Ideas that produce motion despite affective conditions. It’s about the right now and the everyday. It‘s about how we relate to one another. It’s about relations between beings and the planet. It’s about understanding that this planet is our spaceship, and we die without it.

Art at its best gives much and demands little in return. Wouldn’t it be marvelous if we applied that ethic to every other aspect of life?