In the summer of 2018, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents brought hundreds of people—flown thousands of miles from the Mexico–US border—to the Albany County Jail in upstate New York. With the Trump administration’s immigration policies in full force that summer, ICE and Border Patrol agents were tearing families apart, putting children in cages at the southern border, and moving their parents to private detention centers, state prisons, and local county jails all over the country. By July, 330 of these migrants detained by ICE were being held at the Albany County Jail.

Albany County has a 1,040-bed jail across from the Albany Airport. Originally constructed in 1931, the jail was rebuilt and expanded in the 1980s at a cost of $30 million, with renovations and further additions in the years following. Over the last four decades, numerous other counties—both across New York and nationwide—have been building new and bigger jails at enormous cost. Altogether, these developments amount to a vast expansion of carceral capacity, much of it in rural counties and regional cities like Albany. Incarceration rates have been rising in much of the country, even as incarceration rates in large metropolitan areas have fallen. The jail boom in rural America, fueled in part by federal policies, is being used by federal agencies like ICE and the US Marshals Service (USMS).

There are over 3,000 counties in the United States, and almost every one has a jail, usually run by the local sheriff’s department. ICE and the USMS use space in many county jails to detain immigrants, people seeking asylum, and those in pre-trial custody on federal charges. Federal detention in county jails is an often-overlooked facet of mass incarceration in the US. During the past four decades, this relationship between federal agencies and county jails has encouraged jail expansion, and has, in many cases, rewarded anti-immigrant policy among sheriffs and county administrators. At the same time, increased jail capacity nationwide has provided ICE with more sites for detention, forcing advocates and organizers to find new approaches to combat the arbitrary and capricious ways that federal agencies can transport people to jails and detention centers all over the country.

The USMS and ICE’s practices of issuing per diem payments to sheriff’s departments for the use of county jails has created incentives for local administrators to build bigger jails and increase operating budgets. The revenue this excess jail capacity generates then subsidizes the cost of detaining and incarcerating local people, and, in many cases, offsets the enormous local costs of jail construction or renovation. This $1.3 billion-a-year federal market for jail beds has resulted in a carceral arms race, with counties competing to produce more capacity to lock people up, in turn creating a geographically dispersed and flexible resource for agencies like the USMS and ICE.

This federal jail bed market was created in part by the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984, a bill sponsored by Senator Strom Thurmond and championed by then Senator Joe Biden and other Democrats, as well as the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996. The 1984 act increased the average number of people detained by the federal government by 32 percent within a year and increased demand for flexible detention capacity in the United States. Federal criminal caseloads almost doubled in the 1980s, growing from 28,921 in 1980 to 47,411 in 1990. The new “tough on crime” policy at national level soon had an effect at the local level, too. Local jail capacity in the US had grown by less than 1 percent each year between 1978 and 1983, even declining in 1984. But in the wake of the 1984 act, counties began to build, and jail capacity jumped by 4 percent in 1985 alone. Countrywide, county jail capacity doubled over the following decade.

The 1996 act further increased the federal demand for flexible detention space. This bipartisan legislation, which was supported by Biden and signed by President Clinton, transformed immigration law and border enforcement and expanded the federal detention market in two ways: first, it defined new federal crimes related to border crossing, offenses for which people are often held in USMS detention in local jails. People charged under these provisions made up about 10 percent of all bookings into federal pre-trial detention in 1996, but constituted 40 percent of USMS bookings in 2008 before the end of the Bush presidency. They have remained at high levels across both the Obama and Trump administrations.

The 1996 act also increased the number of people detained in Immigration and Naturalization Service (later ICE) custody from under 80,000 in 1995 to more than 180,000 in 2000. The law tied criminal law to immigration law more closely than ever before, increasing the number of people subject to mandatory detention and summary removal from the country without the right to appear before an immigration judge. And Clinton era legislation intensified the effect of racist policing practices for immigrants of color, who were thrust into a newly streamlined criminal justice system–immigration enforcement pipeline.

Advertisement

Through the early 2000s, the federal government continued to fuel local jail capacity expansion with planning support and direct capital funding. That aid has since shifted to a different model: now, funding flows to counties via payments for detaining immigrants and people facing federal drug charges—people criminalized as a consequence of racist federal policies. This is incarceration as a service, whereby the federal government pays local agencies for jail cell space, and counties use the money from the federal government to secure funding on the municipal bond market, via convoluted nonprofit shell companies and lease-purchase agreements. As a result, only a small share of people detained by the federal government are held in federally run facilities, with most people facing federal criminal charges held in the growing network of mostly rural jails.

Although the increased demand for flexible detention from the 1980s to the present is staggering, contracts between local governments and federal agencies for detaining immigrants date back to 1950. In this way, ICE and the USMS work in tandem. This was the case for Albany County, which had signed a contract with the USMS, and not with ICE, long before the immigration policies of Jeff Sessions, Stephen Miller, and Donald Trump. By fiscal year 2019, almost half of all people detained pretrial while facing federal criminal charges were charged with immigration-related “crimes” created in the 1990s such as illegal border crossing, up from about one in three in 2016. As a recent Government Accountability Office report to Congress confirms, ICE staff believe that using USMS contracts are “the fastest and easiest option” for the agency to expand detention capacity.

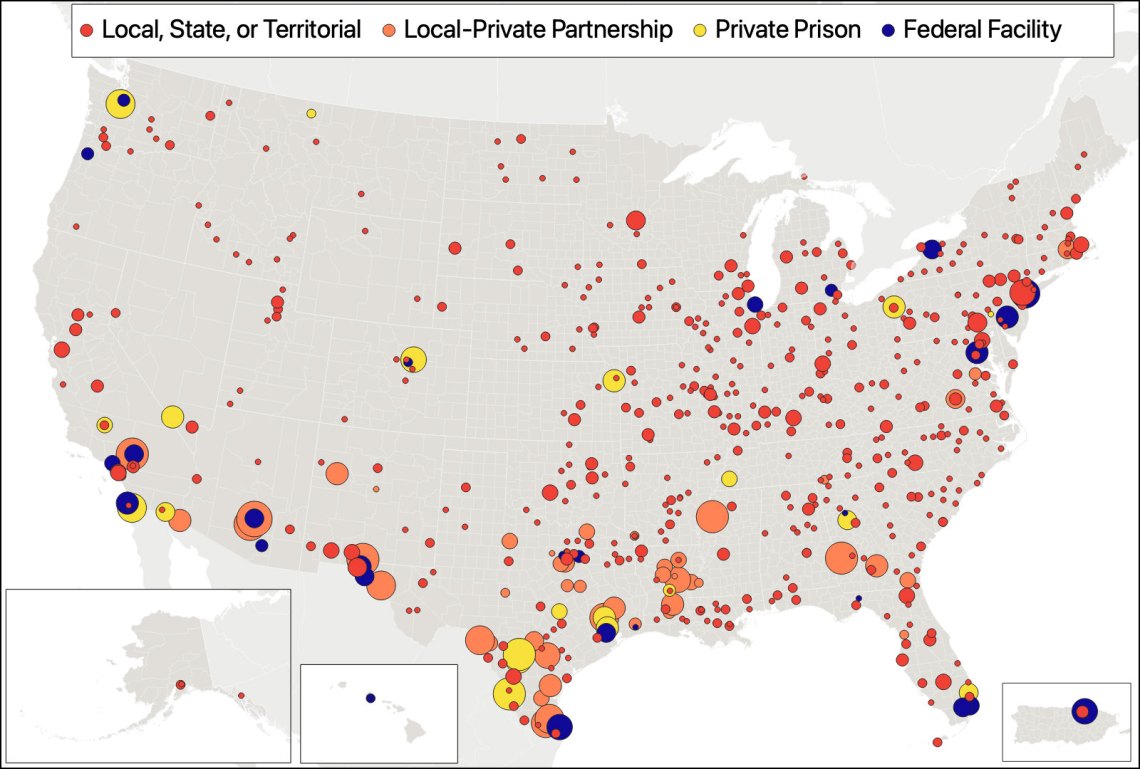

During the summer of 2019, when federal detention (by both ICE and the USMS) was at a peak, there were nineteen states in which all of those facing federal charges or deportation were locked up in local jails. Another fourteen states used a combination of local jails and a few state prisons for federal detention. Only two states primarily used federal facilities, and four primarily employed private facilities. The geographic extent of federal detention and the local jail bed market laid out here is based on documents obtained from the US Marshals by a Freedom of Information Act application and from ICE through new congressional disclosure requirements, and has not been previously reported.

Federal agencies often circumvent contracting directly with private prison companies by using local governments as an intermediary. To avoid open-bid requirements that come with more public transparency and accountability, federal agencies will contract with a local government, which in turn contracts directly with private, for-profit detention providers. Money then passes through to the company, with the local government taking a cut for administrative services. For example, through a contract with Tallahatchie County in the Mississippi Delta, the USMS has used a CoreCivic prison to incarcerate people from all over the US and US territories, including Puerto Rico, South Texas, and the District of Columbia. ICE’s contract with CoreCivic for a detention facility in South Texas was run through the city of Eloy, Arizona—a practice that the Department of Homeland Security’s own inspector general found contravened federal procurement regulations. For the ICE detention facility in Charlton County, Georgia, operated by the GEO Group, ICE’s contract is with the county, which takes a small $2,500 fee, before passing on a $1.9 million per month payment to the GEO Group, according to the Atlanta Journal Constitution.

In the wake of President Biden’s recent executive order directing the Department of Justice not to renew contracts with private prisons, there have been calls to end the use of private immigrant detention facilities by the Department of Homeland Security, whereby private companies administer a larger share of detention capacity compared with that of either the USMS or the Bureau of Prisons. As the geographer and abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore has explained, however, private prison companies are parasites on the publicly owned system, fed by the 1984 crime act and the 1996 immigration act. This federal funding has also helped to reshape local politics across the United States, shoring up county elites that organize to invest in jails and police in lieu of real economic and social development. While the private prison industry may be a soft target for some progressive politicians, the underlying problem has always been racist criminalization and public investment in policing, detention, and incarceration.

Advertisement

Over the course of 2020, prison and jail populations across the country did decline, as the Covid-19 pandemic made incarceration even more of a public health crisis and the national wave of Black Lives Matter demonstrations and accompanying demands to defund the police and #FreeThemAll influenced policy. Jail and prison populations went down 13 percent between early 2020 and the end of September, while federal prison populations dropped by 15 percent, as a recent report from the Vera Institute, for which we work, found.

ICE detention has fallen steeply since January 2020, thanks in part to border closures and in part to the “Remain in Mexico” policy that forces asylum seekers to wait in Mexico for their cases to be heard in immigration hearings held remotely. (ICE’s budget has not been substantially reduced, however, and some advocates fear that the agency will increase detentions as border restrictions are relaxed and asylum seekers are allowed to reenter under the Biden administration’s restoration of pre-Trump era immigration protocols.) The number of people detained by the USMS fell only slightly before increasing again at the end of the year. There are now more people detained by the USMS than at any time in the agency’s history: nearly 64,000. Any reduction in the incarcerated population from the past year remains a fragile gain in 2021—jails and prisons nationwide are still open, their budgets fully funded.

*

When hundreds of people were sent to the Albany Jail that summer of 2018, local immigrants’ rights advocates mobilized to provide support. Today, immigrants in detention can access a New York State–funded attorney once their case goes before an immigration judge through the New York Immigrant Family Unity Project. When people were transferred from the border to Albany in 2018, however, they still had to earn the right to have their asylum cases heard by an immigration judge. First, they needed to demonstrate that they had a “credible fear” of returning to their home countries. Local advocates—led by the Immigration Law Clinic out of the Albany Law School, the New York Immigration Coalition, and the Legal Project—coordinated with Albany’s Sheriff Craig Apple to connect the detained people with legal support. In the end, 93 percent of those detained were deemed to have demonstrated credible fear and were able to bring their asylum cases to court. Most were then represented by Family Unity Project attorneys, who went on to fight with them for the right to remain safely in the United States.

For his part, by the fall of 2018, Sheriff Apple had persuaded the county legislature to redirect some of the revenue from ICE to services for immigrants. The legislature agreed to allocate $170,000 of the nearly $4.8 million in per diem payments toward immigrant legal representation, community outreach, and training for law enforcement. The county also allocated over $940,000 in revenue from ICE to provide property owners in Albany with a tax cut in 2019. For the Albany Times Union, Mallory Moensh reported Sheriff Apple saying: “We’re going to continue to show compassion, mercy, kindness and restore human dignity to these people by simply reinvesting a tiny bit of money that we’ve made off of their incarceration.”

In the spring of 2019, the sheriff sent a letter to the US Citizenship and Immigration Services Albany Field Office stating that the Albany County Jail would no longer house people who had not been arrested on a judicial warrant, effectively limiting ICE, which makes arrests on administrative warrants, from using the facility. By the summer of 2019, ICE was no longer sending immigrants to the Albany County Jail. “ICE didn’t feel they had control of the facility [the Albany County Jail], and it was interfering with their bottom line, which is deportation,” one local advocate told us.

But because increased federal demand has helped spur new capacity since the 1980s, federal agencies have options. ICE now sends people to the Federal Detention Facility in Batavia, in western New York, and to the Rensselaer County Jail. ICE is also currently using the Orange County Jail, the Clinton County Jail, and the Montgomery County Jail, and has the ability to detain people in Chautauqua, Allegany, and Monroe Counties. And that is just in upstate New York.

The Rensselaer County Jail is a 473-bed jail in South Troy, across the river from Albany. Built in 1992, it was expanded by 192 beds in 2007. In January of 2018, Rensselaer County Sheriff Pat Russo signed a 287(g) agreement, a provision in the federal immigration code allowing local law enforcement to be deputized as ICE agents, giving them the power to detain and deport people based on immigration status under administrative warrants. Rensselaer County is the only county in New York State, and one of only seventy-five in the country, to have such an agreement with ICE.

Back in 2007, Rensselaer County commissioners and the sheriff looked to the revenue that the nearby Albany County Jail was generating from the US Marshals Service. The local paper, the Troy Record, quoted a statement from the then Albany County Sheriff: “Thankfully, the members of the Albany County Legislature had the foresight to look to the future while they planned the renovation and expansion of the old jail.”

Counties that built enormous jails have indeed planned for the future—one in which incarceration rates in rural and small metropolitan areas are now more than double those in large metro areas. They were also ready for the Trump administration, which, however incompetently, used the infrastructure on hand to increase federal detention by 30 percent. After decades spent in the Senate pursuing tough-on-crime policies that encouraged and resourced jail construction, President Biden has now committed his administration to advancing racial equity, supporting underserved communities, and welcoming immigrants. To make good on these promises, he will have to overturn his own legacy.