In 1733, four years after his return from England, where he’d been exiled for humiliating a French aristocrat, Voltaire wrote a series of philosophical letters describing England’s system of government and its embrace of free trade and religious tolerance. Written in a deliberately faux-naif style, Voltaire’s Letters Regarding the English Nation appear, at first glance, to be a satire of England’s peculiar customs. The English are “fools and madmen,” Voltaire begins his eleventh letter, On Inoculation: “Fools, because they give their children the smallpox to prevent their catching it; and madmen, because they wantonly communicate a certain and dreadful distemper to their children, merely to prevent an uncertain evil.”

Voltaire was not describing vaccination as we know it today but its precursor, variolation, whereby practitioners would take a small amount of pus from a lesion on a smallpox victim and introduce it under another person’s skin in the hope of inducing an immune response. However, on closer reading, it’s clear that far from being an anti-vaxxer, Voltaire was a supporter of variolation and his real targets were opponents of empirical science. Describing smallpox as a “cruel disorder” that kills one in three of those infected and leaves survivors “horribly disfigured,” Voltaire asks rhetorically: “Aren’t the French fond of life? Do their women not care about their beauty?”

Voltaire was right to be concerned by French resistance to the procedure. In 1723, smallpox killed 20,000 Parisians, including Voltaire’s close friend Génonville (Voltaire also contracted the disease but, after being copiously bled by a doctor, miraculously survived). By contrast, Voltaire explains, in England and countries such as Turkey where variolation had been widely adopted, no one inoculated against smallpox had “ever [been] known to die” and “no one is marked” by the disease.

Were he alive today, Voltaire would no doubt be appalled to learn that despite three hundred years of scientific progress, France remains the most vaccine-hesitant nation in the world, with one in three French people believing that vaccines are unsafe and nearly half saying in November 2020 they would turn down a coronavirus jab, compared to 21 percent in the UK.

On the other hand, he would be encouraged to learn that, thanks to President Emmanuel Macron’s decision in the summer of 2021 to issue vaccine passes, with proof of a second shot required to visit a restaurant, gym, concert hall, or sporting event, 80 percent of the population is now double-jabbed. Yet, in Britain, where the government has so far resisted mandatory vaccines and been reluctant to adopt strict Covid-19 control measures, immunization rates are stuck at 70 percent.

Certainly, this fall, I felt far safer visiting Paris—where I was required to mask up and present my vaccine pass at the Eurostar check-in desk at St. Pancras International and again at a brasserie on the Île Saint-Louis—than I did living in London, where, until recently, mask-wearing was not required in public spaces and, to judge by the conversations in the locker room of my local gym, many young people remain vaccine hesitant.

There are many theories as to why, despite the strides made in vaccinology, the populations of mature Western democracies remain resistant to vaccination. Some people’s suspicions may stem from revelations about past unethical medical practices, such as the 1932 Tuskegee syphilis study in which hundreds of Black men in rural Alabama went untreated for syphilis for forty years. Others may be concerned about rare adverse events, such as the blood clots associated with AstraZeneca’s coronavirus vaccine. Another theory is that the present generation of parents has grown complacent: they are no longer familiar with the infectious diseases of the twentieth century that were successfully suppressed by vaccines, such as measles, which used to render children blind and deaf, and polio, which in one in two hundred cases causes irreversible paralysis and often left survivors dependent on iron lungs to breathe. Instead, it is the remote risks of vaccines that they fear.

In the history of anti-vaccination sentiment, the disgraced English physician Andrew Wakefield’s flawed 1998 Lancet paper linking the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine to autism looms large. Certainly, since Wakefield fled to Florida in 2010 and was embraced by prominent anti-vaxxers such as Robert Kennedy Jr., support for his bogus theories has grown on social media, and spawned a toxic network of anti-vax websites, YouTube videos, and discussion threads. (Make no mistake, this is big business: according to a report by the Centre for Countering Digital Hate, the anti-vax industry boasts an annual income of $35 million and generates advertising revenues of $1.1 billion for tech companies such as Facebook and Twitter.)

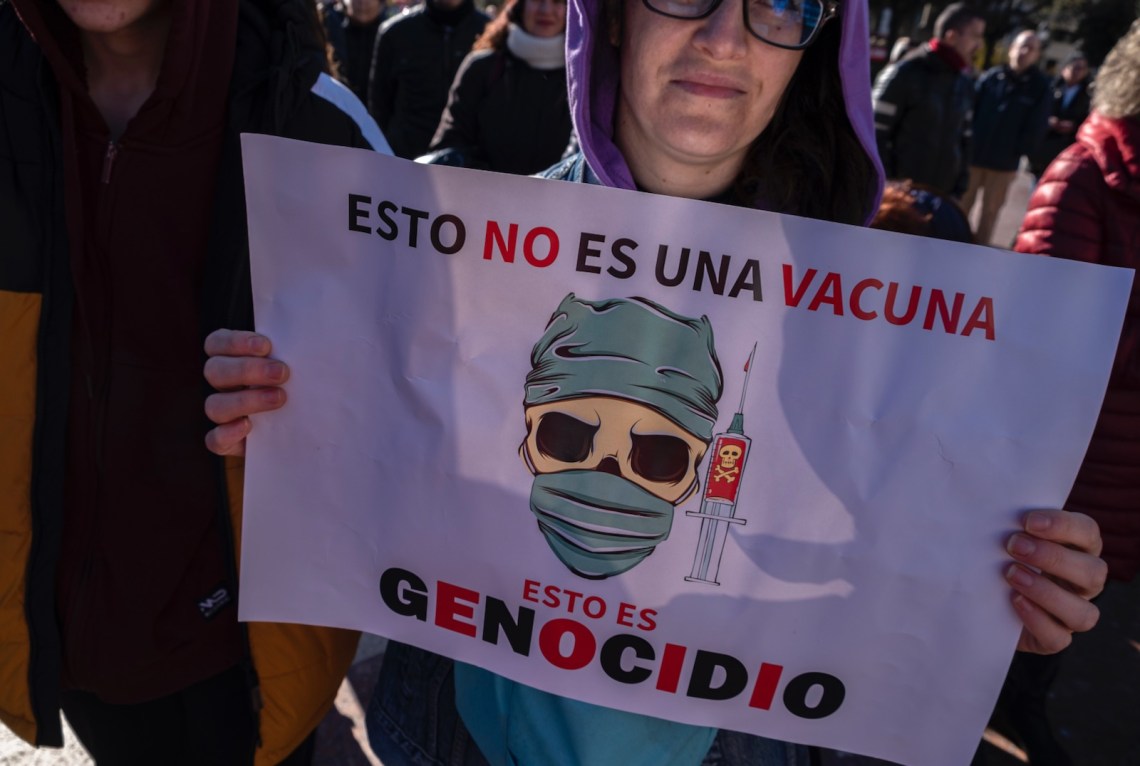

The upshot is that, from Melbourne to Munich and Memphis, regulations requiring people to present proof of coronavirus vaccinations are drawing increasing ire from anti-vaxxers and populist politicians. In the United States, one in five adults are reportedly opposed to coronavirus jabs and the governors of several Republican states have come out against vaccine mandates for health workers and schoolchildren. Meanwhile, the wilder fringes of the anti-vax movement are convinced that Covid-19 is being spread by 5G technology and that vaccines are a plot by Bill Gates and Big Pharma to microchip and “enslave” the populations of Western democracies.

Advertisement

Most worrying of all is the situation in Austria, where low vaccination rates have seen the ruling conservative People’s Party instigate a fourth national lockdown and grant the police extraordinary powers to issue on-the-spot fines to anyone who fails to meet the “2G” rule (one “G” for geimpft, meaning vaccinated, the other for genesen, meaning recovered). In response to this crackdown, some Austrian anti-vaxxers have likened their situation to the persecution of Europe’s Jews under the Nazis and have taken to wearing yellow stars bearing the phrase “ungeimpft” (unvaccinated). Such analogies are odious and historically illiterate: Jews were forced to wear identification that singled them out for abuse and later made it easy to deport them to extermination camps. By contrast, no one has proposed rounding up and gassing anti-vaxxers; on the contrary, in many cases vaccines make the difference between life and death.

All of which poses the question: Why, more than any other medical procedure, do vaccines provoke such heated passions?

One answer lies in the history of the state’s attempts to compel compliance through vaccine schedules, particularly in England during the Victorian period. Under the Compulsory Vaccination Act, which originally came into force in 1853 and was amended in 1867 and 1871, failure to vaccinate a newborn before the age of four months could result in a fine of twenty shillings and imprisonment. As the medical historian Nadja Durbach shows in Bodily Matters (2004), her excellent study of Victorian opposition to the act, resistance to vaccines stemmed from a constellation of factors, including concerns about the expanding influence of the state, beliefs in the rights of the individual, and ideas about the sanctity of the human body.

Opposition was particularly fierce among middle-class adherents of the relatively new discipline of homeopathy, as well as the working classes, who regarded vaccine mandates as an infringement of their liberties and a violation of their children’s bodies. (The growing popularity of homeopathy in this period can be seen as a reaction to the professionalization of medicine and the attempt by orthodox practitioners to assert a monopoly over medical practice and theory.) In cities such as Leicester in the Midlands, where magistrates freely handed out fines to parents with unvaccinated children, and in Keighley in Yorkshire, where several members of the local medical board were imprisoned for refusing to enforce the law, opposition to vaccination became a badge of honor. Robert King, a Leicester man, was fined in 1877 for failing to vaccinate his child even though the child had since died (of causes not recorded); his treatment by the authorities transformed him into a martyr for the Anti-Compulsory Vaccination League. (The league was founded in 1866 by Richard Butler Gibbs, a noted vegetarian and food reformer. Like other anti-vaccination groups, such as the National Anti-Vaccination League, founded in 1874, its members also tended to be vegetarians, anti-vivisectionists, and supporters of temperance. By 1870, the AVCL had 103 branch leagues and claimed 10,000 members.)

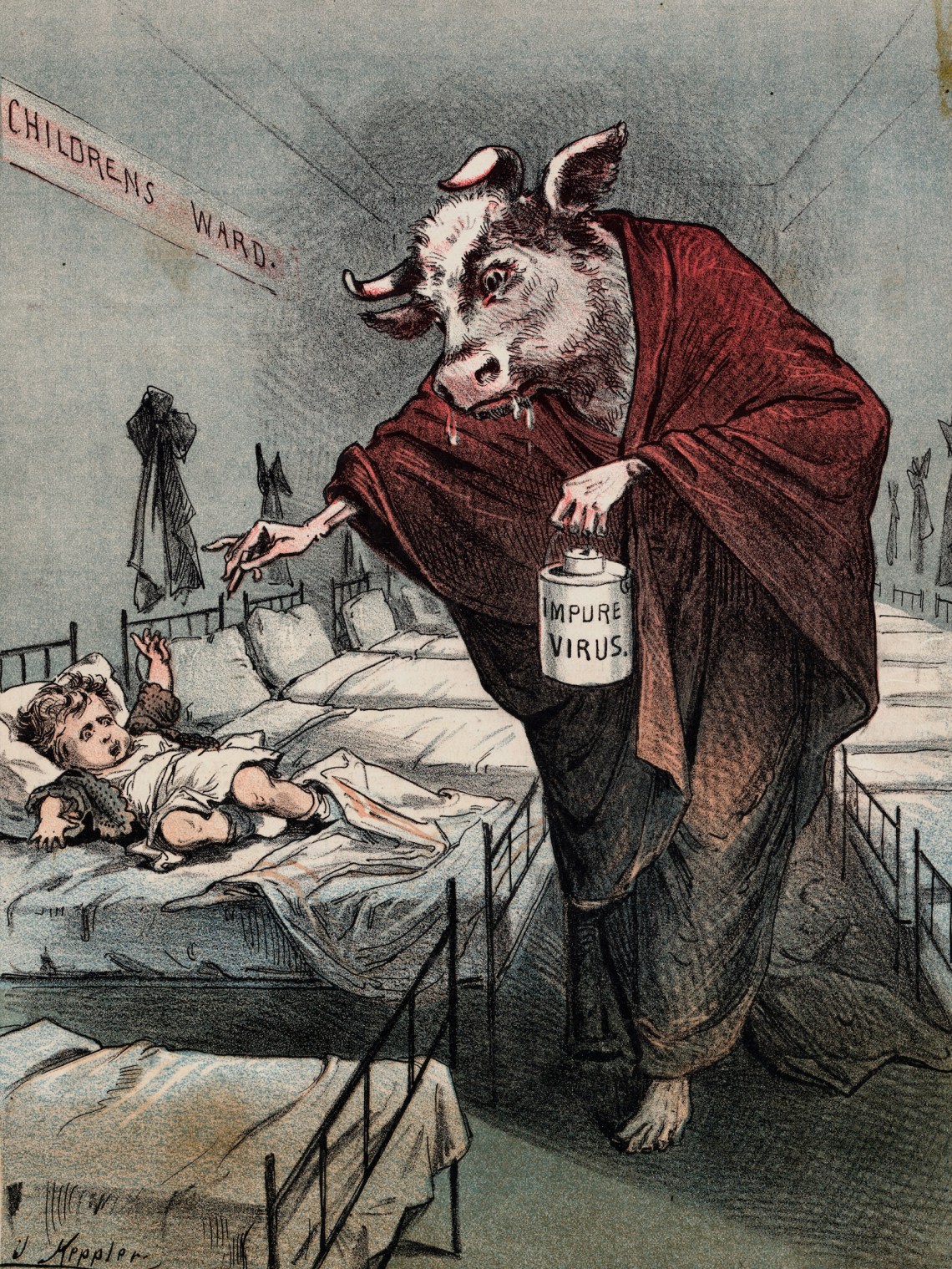

Another reason vaccines elicit strong emotions, as the nonfiction author Eula Bliss observes in her book On Immunity (2014), is that the act of inoculation—the word comes from the Latin word for graft or implant—lends itself to a wide array of metaphors, from the “scarring” of flesh, to the “contamination” of blood, to the “violation” of the body. During this time, anti-vaccination advocates drew on Gothic tropes about vampires and vivisectors. For instance, in an 1881 handbill, “The Vaccination Vampire,” the homeopath J. J. Garth Wilkinson portrays the vaccinator as a “bloodhound” hunting down childbearing women and contaminating their milk with his “poisoned lancet.”

This is hardly surprising given the way that our bodies prime our metaphors and metaphors govern the way we think and act. Nor are such fears necessarily irrational. In an era before standard manufacturing procedures, vaccines were frequently unsanitary and unsafe procedures that exposed patients to real risks. This was particularly the case in the 1870s and 1880s when, to preserve vaccine supplies, vaccinators would use the “arm-to-arm” method to extract “lymph” from children with the best vesicles, or sores, before inoculating the new day’s arrivals. Little wonder that many parents feared the procedure would result in their children being accidentally infected with syphilis and other blood-borne diseases, a fear captured by the image of the Vaccine Upas Tree, a supposedly toxic tree that was used in political cartoons, including those popularized by anti-vaccinationists, as a metaphor for anything that was poisonous.

Advertisement

Nor were such fears then confined to the masses or the scientifically illiterate, any more than they are today. The meanings attached to inoculation are fundamentally bound up with authority: who gets to wield the needle, and who doesn’t. When, in the 1720s, in the midst of a smallpox outbreak in Boston, the Puritan preacher Cotton Mather, who had lost his wife and several children to measles, smallpox, and other diseases, became an advocate for variolation, the fiercest opposition came from the New England medical establishment. (Although Mather was also disliked in Boston because of his involvement in the Salem witch trials, he was also a member of the Royal Society in London, the leading scientific society of its day.)

It was in 1796 that an English country doctor named Edward Jenner discovered a far less risky method of immunization, using pustules from milkmaids infected with the cowpox virus (a cousin of smallpox that caused a far milder disease, yet was closely related enough to confer immunity to smallpox). Yet the procedure was painful: it entailed scoring the flesh and smearing calf lymph into the cuts, and by the 1860s most working people preferred variolation by a local “wise woman” to the lancet of an unfamiliar medical officer.

Much as today, Victorian-era vaccine hesitancy was tied up with distrust of the medical profession and of the power of the modern state. In that period of imperial expansion, it became increasingly important for nations to regulate the health of their populations against epidemics of smallpox, cholera, and other preventable diseases that had the power to roil economies and topple governments. Authorities thus defended mass immunization as a rational scientific program, undertaken for the common good.

Today, whether we realize it or not, we are all implicated in this biopolitical calculus. While most of us are happy to submit to vaccination in our own and other peoples’ interests, a recalcitrant minority see it as an affront to their liberty and freedom of choice. That conflict has been more or less a historical continuum. What is surprising, and demands more explanation, is the persistence of a fear of harm caused by vaccines in the face of overwhelming scientific evidence that vaccination is a boon to health and, for the most part, safe.

Voltaire would have been fascinated by this phenomenon. His letters were in part an attempt to contrast the empiricist psychology of John Locke with the a priori speculations of his countryman René Descartes. Voltaire apprehended that, in its purest, abstract form, reason could be a cul-de-sac that leads one to doubt everything. Instead, he advocated tempering rationalism with observable facts about the world, an empirical approach that was exemplified by Isaac Newton and other leading English scientists associated with the Enlightenment.

What Voltaire could not have foreseen about the situation we face today is that conspiracy theorists would seek to undermine trust in the scientific establishment by turning its observations against it. A prominent feature of contemporary anti-vax websites is that they are not afraid to engage with the science of vaccinology; indeed, many anti-vaxxers have spent more time studying the literature on vaccines than those who tend to take the findings on trust. The difference is that whereas mainstream scientists accept that theories based on empirical observations may change if a better theory comes along, conspiracy theories are by definition unfalsifiable. They are doubt masquerading as truth, rationalism divorced from empiricism.

Ironically, while we might see in Voltaire’s ideas the intellectual roots of a republican tradition that animated the French Revolution and underpins the authority of the French state, which can today enforce vaccine compliance even on a highly dubious populace, England took a more tolerant, conciliatory path. Faced with increasingly organized protests—in 1885, a 100,000-strong mob paraded through Leicester with an effigy of Jenner and a child’s coffin inscribed “another victim of vaccination”—officials in Leicester varied the regulations to permit vaccine refuseniks to instead quarantine at home for fourteen days (contacts of the original case were also confined for a fortnight). Known as the “Leicester method,” the isolation and quarantine measures took the heat out of the anti-vaccination rebellion.

This was followed, in 1898, after the convening of a Royal Commission to reexamine the case for and against Jenner’s vaccine, by an exemption for “conscientious objectors”. Then, in 1907, Britain abandoned compulsory smallpox vaccination altogether. Although Britain suffered further epidemics of smallpox, in 1902–1904 and 1928–1931, the Leicester method proved surprisingly effective. In 1934, Britain experienced its last indigenous case of the disease.

In America, anti-vaccine sentiments also crystallized around vaccine mandates and concerns about the dangers of vaccines. Protests were particularly marked in Philadelphia, where, in 1907, several people died after receiving smallpox jabs that had been contaminated with tetanus. But whereas, two years earlier, the US Supreme Court had upheld the right of states to set vaccination policies, by 1907 only two thirds of states had compulsory vaccination laws. This only began to change in the late 1970s when, following renewed outbreaks of measles and pertussis (whooping cough), the Carter administration initiated a major federal vaccination drive, with the help of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and celebrities such as Muhammad Ali.

The “no shots, no school” campaign at first paid off. By the end of Carter’s term, all fifty US states had school vaccine requirements, and many required vaccinations for preschoolers. However, in 1982, NBC broadcast the film DPT: Vaccine Roulette, which associated the diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine with cases of encephalopathy in children. Although no causal link was ever proven, the documentary sparked widespread concern and, together with the growing list of required vaccines, marked a watershed moment for the modern American anti-vax movement, mobilizing an army of parents. This new movement would, as the science journalist Arthur Allen put it in his 2007 book Vaccine, “expose US vaccine policies to systematic questioning for the first time in nearly a century.”

The result of these contrasting histories is that while the United States and France today mandate a long list of vaccines for school-age children, in Britain the Victorian experience made politicians and administrators wary of compulsion. Far better, they reasoned, to make vaccines free and easy to access and persuade parents to take up the offer voluntarily through well-orchestrated public health campaigns. (A high degree of public trust in a system of free, socialized medicine, through the UK’s National Health Service, has undoubtedly aided this cause.)

Until now, this has also been Britain’s approach to the coronavirus. Whereas the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and other European countries that require citizens to carry Covid-19 passes have witnessed increasingly violent protests in recent weeks, in Britain, where the government has so far resisted vaccine passports, dissent has been far more subdued. The question, as we enter the third year of the coronavirus pandemic, is whether we are now seeing the limits of this conciliatory approach.

Ever since the coronavirus emerged from an unknown animal reservoir in China at the close of 2019, public health experts have been warning that no country can be considered safe from Covid-19 until every other country in the world enjoys similar levels of herd immunity, the protection from disease that a critical mass of immunized people affords to the vulnerable individuals among them. This is usually estimated to require the inoculation of 70 to 80 percent of the population, either through vaccination or natural infection.

However, as we saw with the surge in deaths among the unvaccinated that accompanied the spread of the Delta variant, natural immunization is a risky strategy. And although it’s too early to say whether vaccines will prove as effective against the recently discovered Omicron strain of the virus, there’s good reason to believe that those who have received three-shot vaccination will be less likely to develop severe disease and require hospitalization than those who haven’t.

For those who refuse to undergo vaccination, though, the only other tools that authorities have to hand are quarantines and home isolations, plus lockdowns and mask mandates—measures that also tend to infuriate those who, like anti-vaxxers, feel the government has no right to dictate citizens’ behavior on health matters. But what worked for Leicester in 1885 may no longer be sufficient. The world is far more interconnected than it was in the nineteenth century: globalization and international travel, together with glaring disparities in public health provision, mean that unvaccinated populations in one part of the world can quickly become breeding grounds for new variants that may spread everywhere faster than we can detect them and isolate cases to prevent further transmission.

Perhaps we have reached the limits of empiricism. Perhaps the time for reasoning with anti-vaxxers is over.