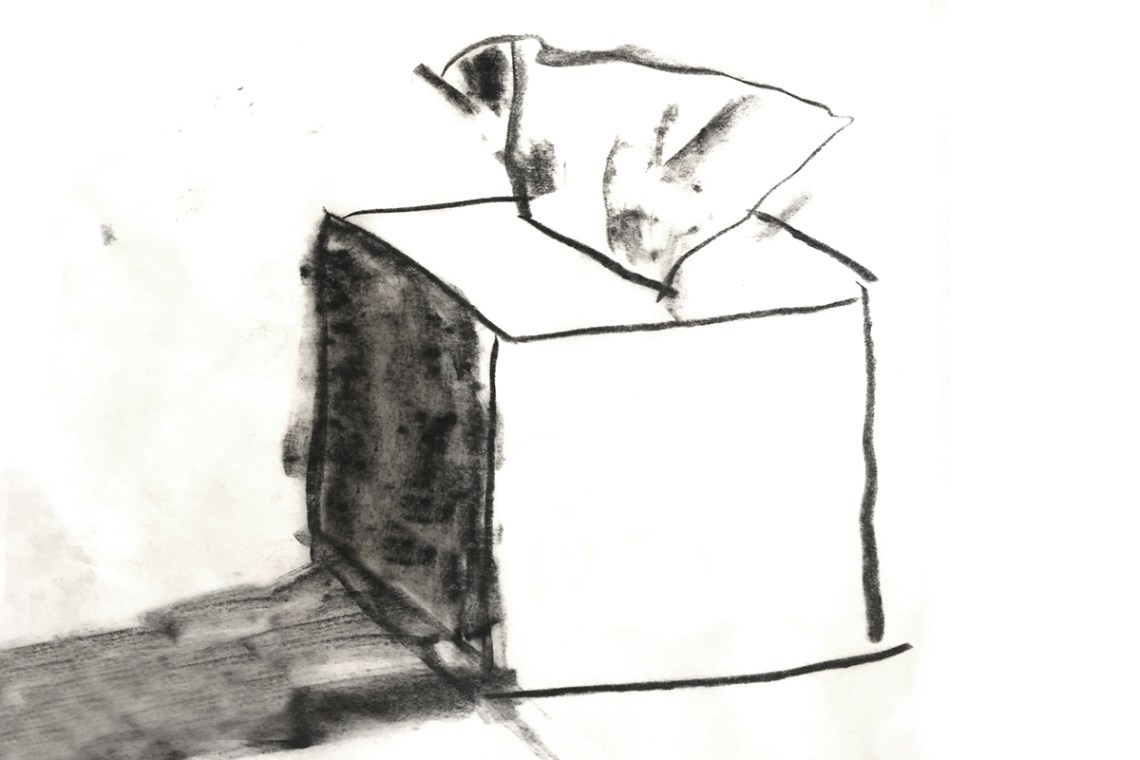

In the windowless clinic where I work, the back hallway is lined with a row of small square rooms. Inside each room is a desk, a computer screen, a box of tissues, two chairs, and little else. This is where the clinic counselors meet with patients—mostly women, some trans or nonbinary patients, anyone with a uterus—who have come in for their abortions.

In those small rooms, most of the day’s work is completed without me. The counselors have a set of questions they’re required to go through with each patient, but often the conversation goes off script. A woman starts talking about the things going on in her life: a fight with her partner, her younger kid’s asthma, her sister’s wedding next week, her mother’s alcoholism. All of it is relevant, if it feels relevant to her; the counselor affirms this with an attentive silence, a sympathetic gaze, the occasional mmmm, ah, I see. Sooner or later they’ll get around to the specific questions critical to today’s visit: Is she certain of her decision and ready to proceed today?

Eventually most patients will walk down another hall to one of the procedure rooms, which are larger, with a more clinical ambiance—equipped with an exam table and stirrups, an electric suction device, sterile surgical equipment, an ultrasound machine. These rooms are where I spend most of my day, performing aspirations.

An aspiration is an efficient, relatively gentle approach to emptying the uterus. It involves a small tube, manual or electric suction, and a circular, back-and-forth motion of my hand and wrist. Today it is how every doctor performs nearly every early abortion; it is also used to manage prolonged or complicated miscarriages. (I cringe when I hear the outdated term “D&C,” which stands for “dilation and curettage” and refers to an old-fashioned, physically harsher version of the procedure involving a sharp-edged surgical scraper.)

Occasionally—perhaps for one or two patients each day—there is a pause, a hiccup in the clinic’s streamlined activity. Before she makes it down the hall for her procedure, I am called into a counseling room to review her case and speak with her.

Like most of my patients, she has come into the clinic for an abortion, or at least to find out if she’s eligible for an abortion. Unlike most of them, perhaps she hasn’t definitely decided what she is going to do. Or she came in because of some symptoms: she is bleeding, possibly miscarrying; she wants to know what I can tell her, what her options are. Or the nurse who performed an ultrasound couldn’t find a pregnancy in the uterus, raising the possibility of an implantation in the fallopian tube or elsewhere.

After we discuss the details of her situation, assuming they don’t present an emergency (uncontrolled bleeding or symptoms that suggest an ectopic pregnancy), I tell her that how we proceed will be largely based on her goals and preferences: Is she certain about terminating the pregnancy, or does she need more time to think about it? If she is already miscarrying, does she prefer the idea of letting her body pass the tissue on its own, or would she like medications or an aspiration procedure to speed up that process? Does she wish to discuss all of this with her partner or a loved one, or would she prefer to decide alone?

She often seems surprised at how much time we spend discussing these personal, nonclinical elements of her decision. When she asks me, “What do you recommend?” I tell her, “There’s no real basis for a medical recommendation in this case. Any of the options I’ve presented are safe and reasonable. It’s a personal decision. It’s really up to you.”

Then I see a look in her eyes, like: You’re kidding. Up to me? Sometimes it is a look of fear, at least at first. But inevitably it transforms into something else: a deep, probing, inward gaze that shows me she is, in my presence, accessing a very private place within herself. I have not provided her access to this place—she can get there without me—but I have given her permission to enter it. To withdraw, for a moment, from me and my medical expertise, from the judgments and biases of her friends and family, from the shouts of the protesters in the parking lot. This is one of my favorite parts of my job: watching her go into that place and emerge from it with a decision—or a thoughtful question, or just a word, or yet another expression on her face, one of resolution or sadness or grief or relief. Whatever it is, it comes from within her. It belongs to her.

Advertisement

She came in for an abortion, and what she got instead, or first, was a glimpse of this: her agency; a vision of what her future will look like, even if it’s just the next few days, or the next week, or the next hour; her self.

These are just some of the many things we stand to lose with the overturning of Roe v. Wade. Those private conversations in windowless rooms. That secret place inside. Those aspirations.