In March 1962 the choreographer and dancer Trisha Brown debuted Trillium, her first original performance, at the Maidman Playhouse in New York City. In the three-minute work, she attempted to sit, stand, and lie down in quick, unpredictable succession. With enough repetition and acceleration, she recalled, she’d reach a point where “lying down was done in the air.”

Brown’s repertory of more than a hundred pieces, composed over fifty years, comes together in such moments of balanced precarity. While her peers at Judson Dance Theater—the postmodern performance collective she cofounded in 1962—made much of everyday motions like walking and running, Brown took those steps and tipped them on their sides. In Ballet (1968) she climbed a ladder, then bear-walked across parallel ropes. In Man Walking Down the Side of a Building (1970), she enlisted her then-husband Joseph Schlichter to tread from the seventh story of a brick building in SoHo to street level, a hands-free harness his only steadying device. In Walking on the Wall (1971), Spiral (1974), and Working Title (1985), dancers in harnesses move horizontally across museum walls, wind themselves around tree trunks, and float above their peers on a proscenium stage. For Brown, who died in 2017, any plane could be a surface for dancing.

She conducted her earliest experiments with movement in Aberdeen, Washington, where she was born in 1936. At five years old, according to the scholar Susan Rosenberg, daring to balance on croquet balls left her with a ruptured appendix: “she fell on a croquet stick.” Learning how to pole vault left her with a penchant for being airborne. Her “yard was slanted,” she remembered, and her older brother “had me starting on the high side. His theory was that if I could get into an arcane area of sports, and I was good at it, then I could beat the Russians.”

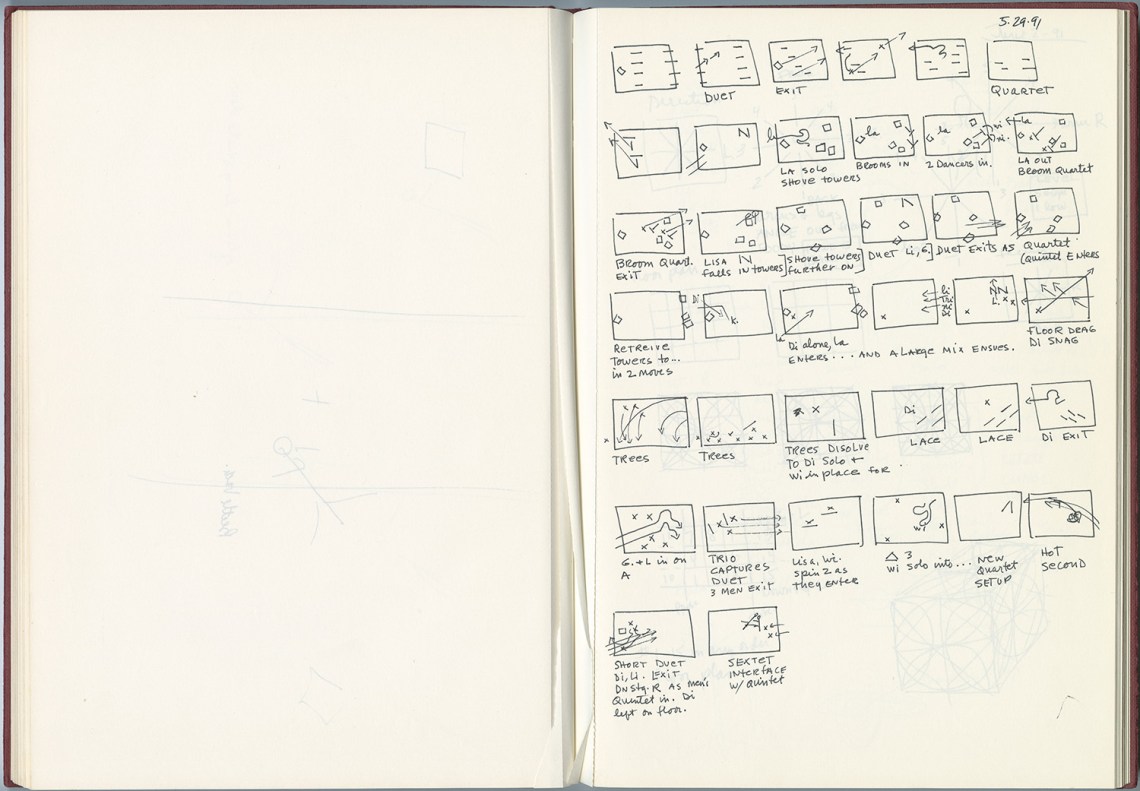

There was great precision and effort behind her dances’ instabilities. She described Son of Gone Fishin’ (1981) as “great tumultuous dancing” undergirded by “regiments of organization.” “If you cut your right hand too wide,” she explained, “you have to take a tuck in the next thing on the left.” In that piece the dancers lurch forward, run backwards, and swing their arms and legs like loose propellers. What could be a prelude to falling becomes, instead, a transition to the next precarious pose. The resulting phrases are like slipknots, moments of tension built to give way. Brown paid close attention to her staging, too: the crevasses of a corporate plaza, the recesses of a gallery, and the wings of a theater were all spaces where even the simplest movements—a flick of the wrist or a lift of the heels—could take on new dimensions. In Glacial Decoy (1979), she pushed the limits of a proscenium stage by having her dancers hover near the wings. For the critic Alan Robertson, this arrangement left open the possibility that Brown had commissioned “dozens, maybe hundreds of dancers dancing along, far away, where we can’t see them”—backstage, just beyond the theater doors, perhaps in New Jersey. She hadn’t, but her dances had sprawled across city streets before: in Roof Piece (1971), fifteen dancers were stationed on downtown New York City rooftops and played a loose game of telephone. As Brown originated improvised movements and passed them down the line of dancers, lunges, arm wind-ups, and hip swivels made their way beyond each dancer’s individual line of sight.

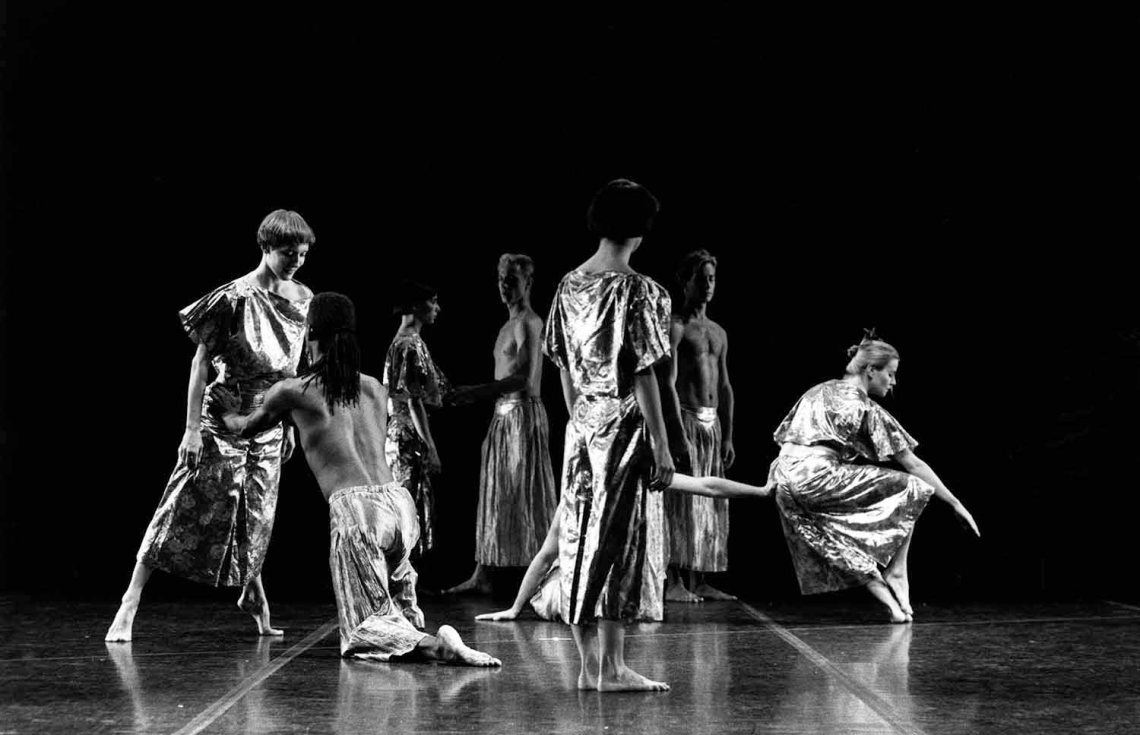

Founded in 1970, the Trisha Brown Dance Company (TBDC) belatedly celebrated its fiftieth anniversary season this May at the Joyce Theater with restagings of Foray Forêt (1990), a tensile twenty-eight-minute work for nine dancers draped in costumes that ripple like colorful liquid metal, and Astral Converted (1991), its arcane, undulating companion. Each features costumes and lighting design by Robert Rauschenberg, a longtime collaborator of Brown’s. Astral Converted has aluminum set pieces from Rauschenberg, too, and music by John Cage, who was a major creative inspiration to her. In both dances, Brown’s ability to choreograph uncertainty—each pivot and trip by a given dancer reinforced by other members of the ensemble, who collectively serve as a sort of bearing system—is on display.

Foray Forêt, first staged for the Biennale de la Danse de Lyon, opens with a cluster of dancers gathering and dispersing toward the back right corner of the stage, each simultaneously attentive to the others’ movements and revolving in solitary orbits. When the group pauses to observe one dancer tipping off balance, a second holds out his hands to brace her, a moment of structure that steels the performance against collapse. “She loved being disoriented,” recalled the dance scholar and former TBDC member Wendy Perron in a lecture given months before Brown’s death. In Foray Forêt, Brown resists consistent dancer couplings and recurring phrases. The dancers variably flirt with the wings of the stage—repeatedly approaching them without exiting—and hover near its center, where they form clusters that bubble and pop, leaving behind gaping holes of black floor. When one creates an L with his body at stage left—his back pressed to the floor, his feet pointing toward the ceiling—another uses him as a springboard to float offstage, her stomach pressing against the soles of his feet, another dancer waiting in the wings to ease her landing.

Advertisement

As a dance student at Mills College and later a teacher at Reed College, Brown bristled at the dominant idea that dances should be choreographed to music. She set her dances to silence instead, and by the 1980s she felt confident that her “dancing [had] its own time.” Music wouldn’t subsume the dancing, but could it add anything? Brown was open to finding out: as Rosenberg asserts in Trisha Brown: Choreography as Visual Art (2017), her incisive history of Brown’s work from 1962 to 1987, “she was impatient with the coughing that threatened to interrupt her silent theatrical performances.” Foray Forêt draws its sonic texture from Brown’s experiences rehearsing in city lofts, where the thrum of car alarms and laughter floated up from the street. Brown’s directions call for a live “local marching band” to play at a distance from the stage.

At the Joyce, it was the five-piece Jina Brass Band, under the direction of Sunny Jain. The band weaves through the theater’s lobby and backstage corridors before briefly, to the delight of the audience, making its way across the stage. The dancers periodically seem to gravitate toward the band but stop short of following them offstage, sly reminders that they are moving with the music but not to it. The Jina Brass Band specializes in “baraat songs, classic Punjabi songs, [and] upbeat Bollywood numbers,” and one of the tunes that ricochets across the performance hall is a rendition of a love song featured in the Bollywood classic Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge. That the film came out five years after Foray Forêt is a reminder that Brown designed her dances to remain contemporary. Each staging of the dance welcomes a new take on what sounds might accompany it.

*

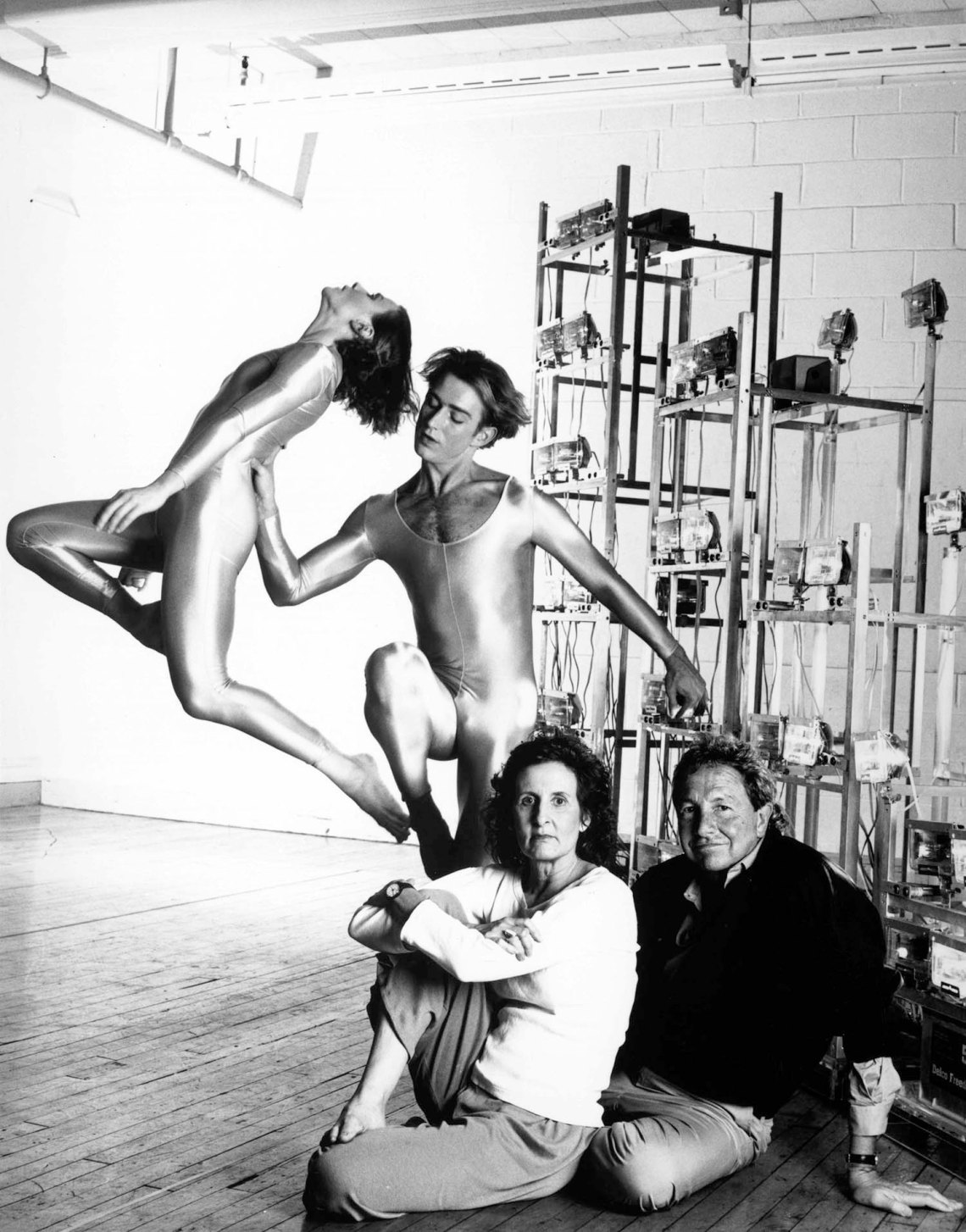

In 1997 Brown wrote about her partnership with Rauschenberg on the occasion of a Guggenheim Museum retrospective of his art. Brown described their working relationship as “a sleight of hand located in the mind, where both participants remain vigilant to their separate disciplines as they cantilever their expectations in suspense of the result.” One had to be prepared, but flexible; on guard, but open to the unexpected. Collaboration was, she concluded, “life and death in the aesthetic zone.” In a 1964 letter to her friend and collaborator Yvonne Rainer, Brown described what it was like to teach dance: “Put out a dance idea and watch 20 imaginations dish it back.” She knew that even the most intricate score would look different on each dancer’s body, or under a different instructor’s direction.

She didn’t fortify her dances against variation but welcomed it through planned moments for improvisation and open-ended instructions like “line up.” It is this foundational receptivity that has kept her work pliable for contemporary restagings. In November 2021 the TBDC, now under the leadership of Associate Artistic Director Carolyn Lucas, gathered a small, in-person audience at the Mark Morris Dance Center for a lecture on and demonstration of Set and Reset (1983), an effervescent group dance that Brown developed using her system of “memorized improvisation,” in which she and a group of dancers would experiment with movement until they had latched onto replicable sequences. (Set and Reset was also a collaboration with Rauschenberg, and for it he designed segmented, gauzy wings that kept the dancers in view even when they had “left” the stage.) In April, the British dance company Candoco restaged that work for a group of disabled and nondisabled dancers across the street at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Just days before the TBDC’s return to the Joyce Theater, Brown’s first male dancer, Stephen Petronio, included a tribute version of her Group Primary Accumulation (1973) in his own company’s Joyce season.

Group Primary Accumulation was originally staged in the sunken plaza of the McGraw-Hill Building in midtown Manhattan, where onlookers peered down at it from street level. Even Petronio’s proscenium staging captured Brown’s attentiveness to the ways a body can transform when it is placed at—and viewed from—different angles. Adapted from a solo work, Group Primary Accumulation features four women lying prone, arranged like rungs on a ladder at center stage. They methodically build a sequence through repetition and addition: pivoting their hips; then pivoting their hips and arching their backs; then pivoting their hips, arching their backs, and clawing at their stomachs; and so on. As the gestures accumulate, each recedes in focus, like a letter swallowed by a word and then a sentence. The women abruptly swing their bodies two times to the left: the sentence has been recast in italics. The audience’s gaze, once drawn to the gap between the floor and the dancers’ arched backs, now fixes on the dancers’ flexed toes. The dancers, previously in a row, are staggered. A smooth formation is now a craggy one.

Advertisement

Astral Converted, adapted from the shorter Astral Convertible (1989), debuted on an outdoor stage at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. and is also meant to be seen from above. “Knowing that our future choreographers are all seated in the third balcony,” Brown explained, “I thought I would make a dance for them.” The dance is wry and technical, with virtuosic shifts in the dancers’ body weight and a keen sense of space, as the performers navigate around each other and Rauschenberg’s aluminum columns, which are placed irregularly around the stage and light up and emit sound when a dancer approaches. It opens with eight dancers arranged in two rows; one group is seated, the other lying down. The prone group flows through a series of gestures similar to those in Group Primary Accumulation and then puffs up to a seated position.

The piece takes off as the dancers, wearing shimmery silver bodysuits, move like electrons, whizzing past one another and sometimes colliding. One performer easily flips another over his shoulder. A second drags his peer, in a fetal position, from stage right to left as she flutters her legs to help propel them both. Two dancers upstage swing a third like a hammock, or a taffy pull. In a standout moment, the veteran company members Leah Ives and Kyle Marshall seem to pass gravity between them. Marshall flips Ives over him one moment; the next, she settles into a chair pose and he rests upon her knee; they cartwheel in tandem. Cool and assured, all nine dancers maintain their composure in a performance that has no central axis or direction. They teeter without a fixed edge.

Astral Converted marks the return of one of Brown’s earliest props. When she attended an outdoor workshop led by the choreographer Anna Halprin in 1960, Brown famously performed with a broom, her feet leaving the floor as she swept. She would later yearn for the time she was “distinctly able to levitate.” Midway through Astral Converted, two dancers step out from stage right, a wooden push broom in each of their hands. They sweep in long strokes around the aluminum structures near the stage wings, alternatively treating the brooms like extensions of their bodies—leverage for gliding and lunging—and tipping them like pas de deux partners. In this dance, friction is just as important as flow. When the dancers sweep toward a pair of seated performers, the latter swerve away just in time to avoid being swept up, the space between them polarized.

“Many people say that my dances are easy and that a basic accountant could do them,” Brown lamented in 1979. “Actually my dances are very structured. They are planned carefully and require immense concentration.” That concentration is demanded not only of her dancers but of her audiences. Astral Converted is not a performance that clings to center stage, its dancers facing only the house, their every step signaled. Instead, it asks viewers to crane their necks and lean forward to see what’s happening behind one of Rauschenberg’s glinting columns. And there’s never just one place to look. As the broom sequence takes place downstage right, a solo unfurls to its left. Are these sequences meant to be taken together or watched separately? Do they reward the attentive viewer—whose rowmate may not have noticed the spectral figure upstage—or prove that even the most rigorous viewing of a Trisha Brown dance will never quite reveal the springs and levers that hold it together? But Brown preempts an easy conclusion. She cuts off the dance mid-sequence with a full blackout; its final gasp comes from the audience.