The spatial and haptic logic of the leporello differs fundamentally from that of the modern bound book. Whereas one can flip rapidly through the pages of a cut and bound codex, the accordion sheet of the leporello requires slower handling and does not so readily give up its secrets. The leporello may, additionally, be fully extended so that it forms a single uninterrupted expanse of paper, not unlike a scroll. Although the leporello did not originate in the West, it derives its contemporary name from Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni, in which the titular cad’s sidekick, one Leporello, lists his master’s prodigious sexual conquests. Artists who employ the leporello as a format for graphic work must contend with its simultaneous narrowness and broadness. The book can be held in one hand or unfolded across a room. It is at once discreet and voluble, discrete and continuous.

The artist Rick Barton, currently the subject of an intimate and refreshing exhibition at the Morgan Library, was a devotee of the leporello form and seems to have embraced its contradictions. Something of a graphomaniac, Barton embellished the folds of numerous slender leporello notebooks with wiry line drawings, frequently depicting queer café life in postwar San Francisco, where he lived from the mid-1950s to the mid-1970s, before moving to San Diego, the city in which he passed away in 1992.

To the extent that Barton is known at all in contemporary art circles, it is as an ad hoc drawing instructor who, over the course of chance meetings at San Francisco cafés, introduced the late Lebanese American poet and painter Etel Adnan to the leporello as a canvas for sketching. In her 1998 essay “The Unfolding of an Artist’s Book,” Adnan wrote that Barton performed a sort of “mystic transfer” when he shared his practice with her. She had watched him generate interlinked faces, bodies, interiors, and landscapes—reproducing the quotidian life swirling around him on pleated pages. Her fascination led him to encourage her to draw. He told her that a book he had been working on was now hers “to continue.” Adnan’s relatively brief account—“a thorough opium smoker and lonelier than a sailor,” “a great intellect,” “should have been a San Francisco legend”—has for some time been Barton’s only entry in the annals of art history. The curator Rachel Federman has greatly expanded his reputation with this show, as well as a biographically rich catalog essay.

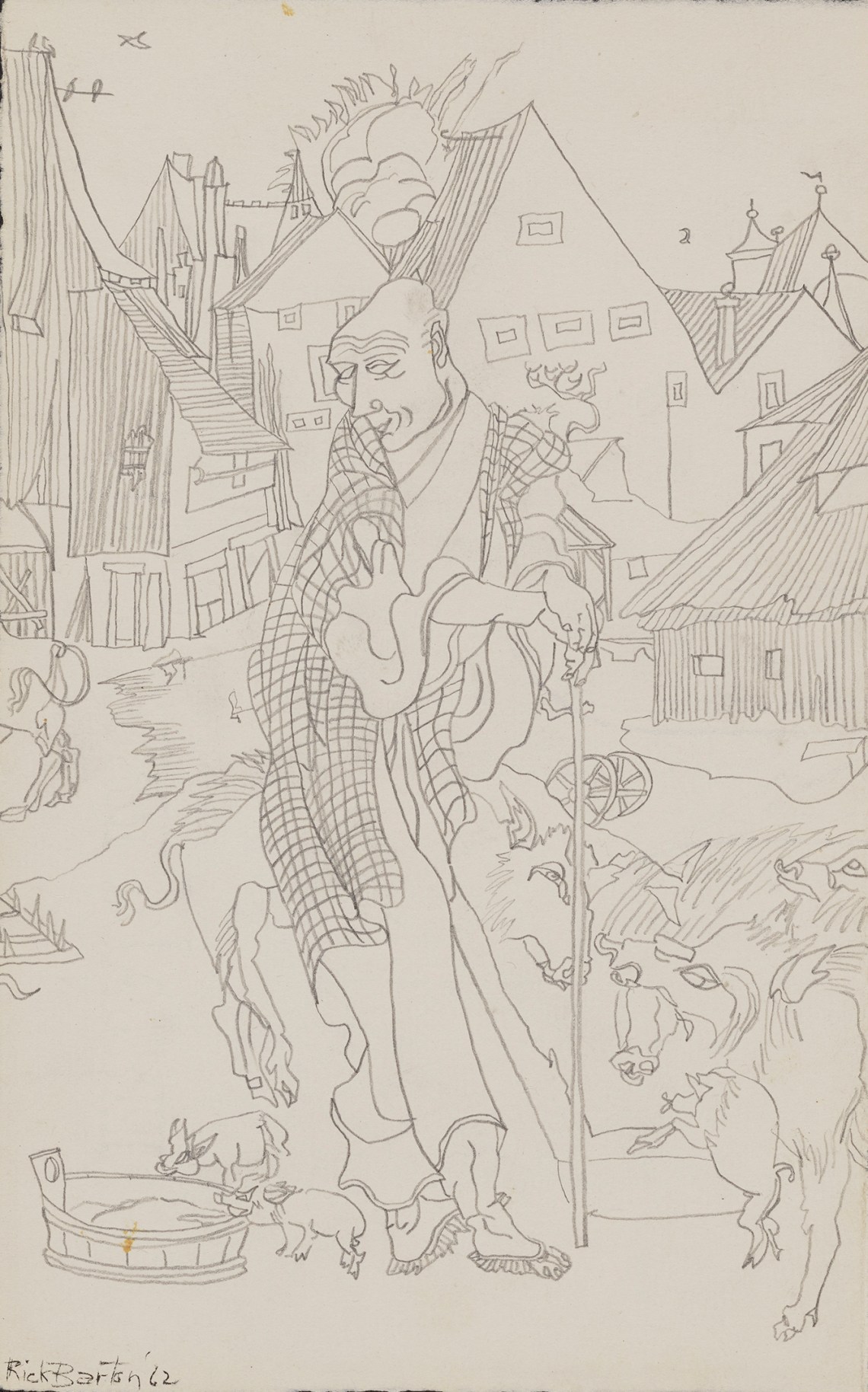

Born in New York City in 1928, Barton experienced poverty and periodic near starvation as a child (his single mother suffered from bouts of severe mental illness). He enlisted in the Navy at the age of seventeen and traveled to Asia, but was honorably discharged after recurring stays in mental hospitals. Although we know via anecdotes from friends that Barton attended Amédée Ozenfant’s School of Fine Arts in Gramercy, Manhattan, it was in China that he was introduced to the style of ink-based drawing that, due to its emphasis on the line, thrilled and consumed him. The Chinese tradition offered a way to conceive of drawing as a genre of nearly linguistic expression. As Barton told Adnan, “One day in Peking I was sitting on the main square drawing a chrysanthemum and a little boy stopped close, looked at what I was doing, and told his father: ‘Look, He is writing a chrysanthemum.’ He was right. I am a writer.”

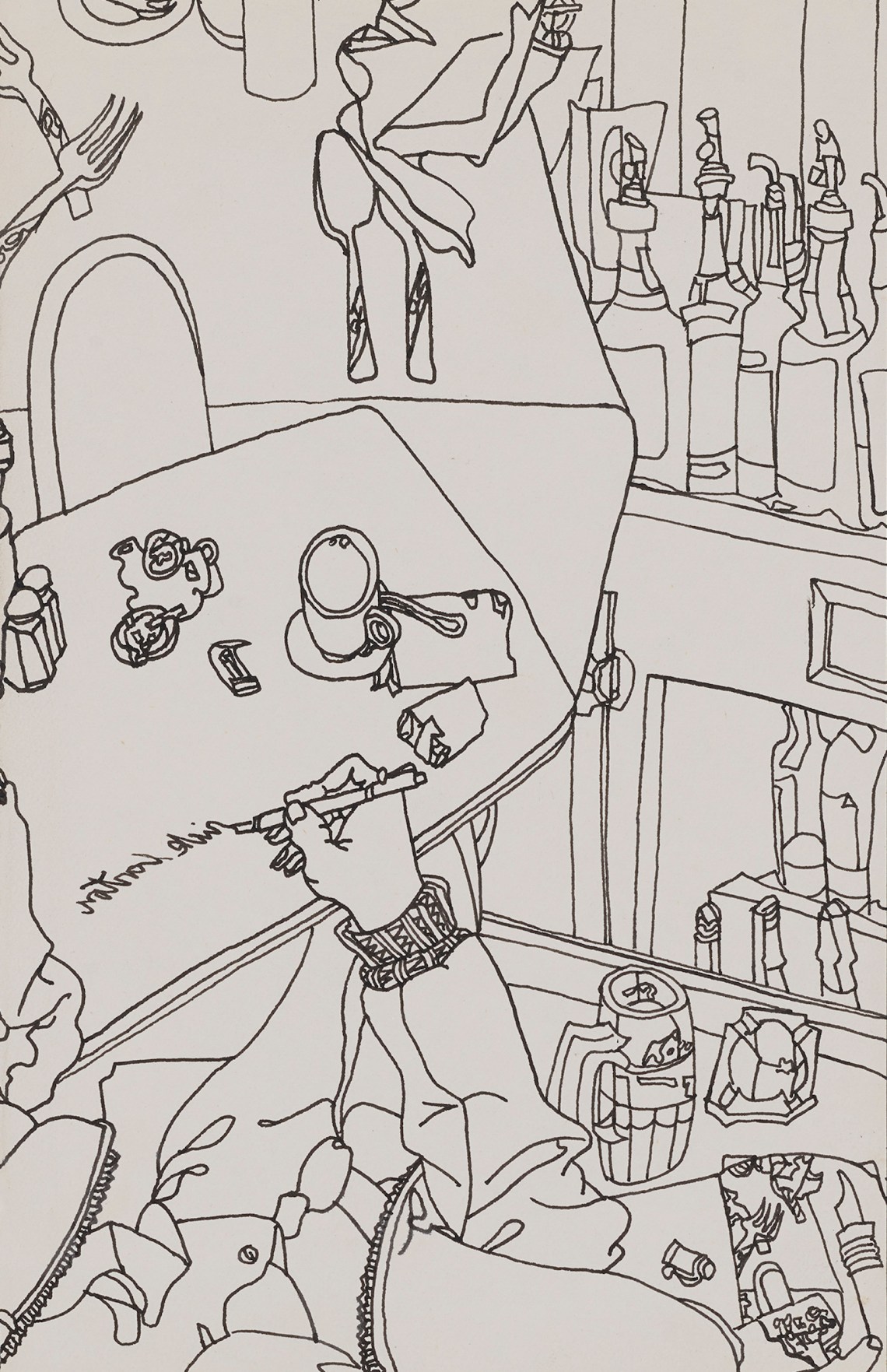

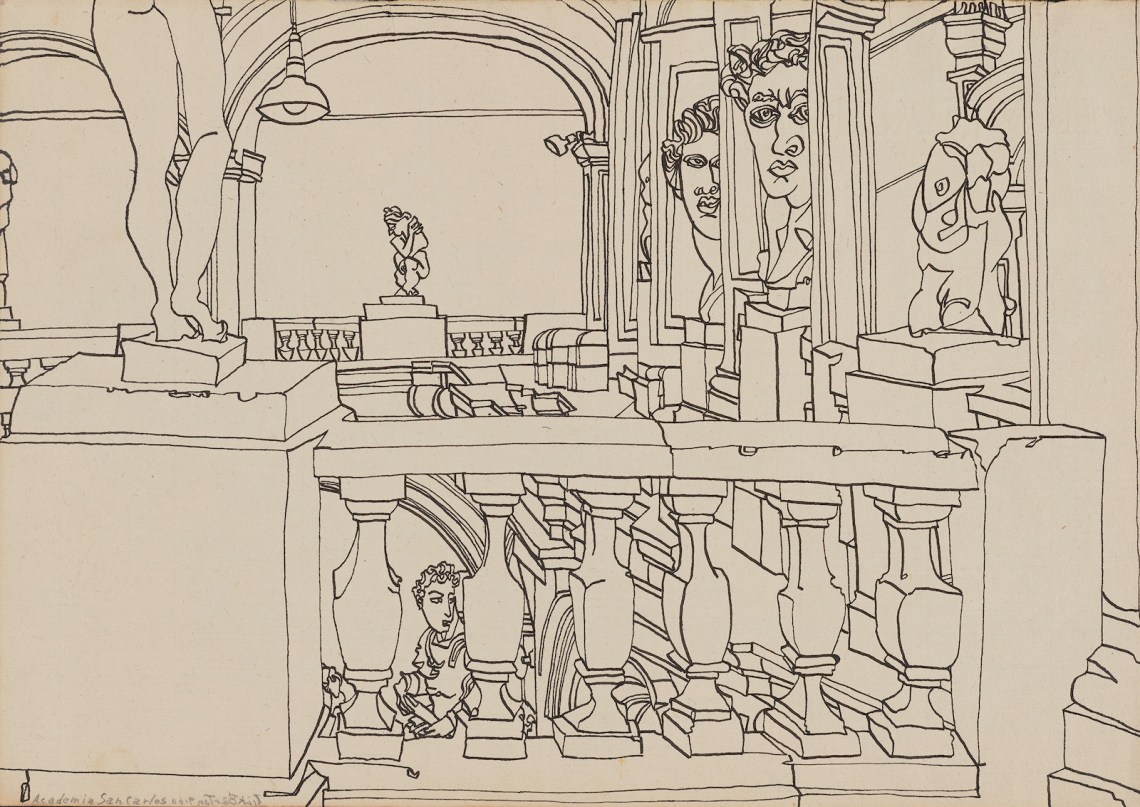

At the Morgan the drawings are grouped thematically to give a sense of Barton’s interests: “Intimate Interiors,” “Social Spaces,” “Ritual and Architecture,” “Flora and Fauna.” The works on the gallery walls, accomplished on single sheets of paper, are intriguing, if sometimes excessively neat. Barton’s linoleum block prints depicting ornate church façades or cluttered domestic interiors are measured and accomplished but no match for his wildly original ink sketches of the most mundane subjects: poorly mounted sinks, spidery pipes and electrical wiring, bare bulbs, backs of chairs. Twice incarcerated, Barton found in the repetitiousness of prison architecture and the expressive faces and bodies of his fellow inmates piquant subject matter for sketching. All these pieces suggest Barton’s place in a larger canon of American illustration; early Andy Warhol comes to mind, along with the antic works of such New Yorker habitués as Saul Steinberg and George Booth. Barton had the style of a graphic designer, coupled with the rapid eye and hand of a cartoonist.

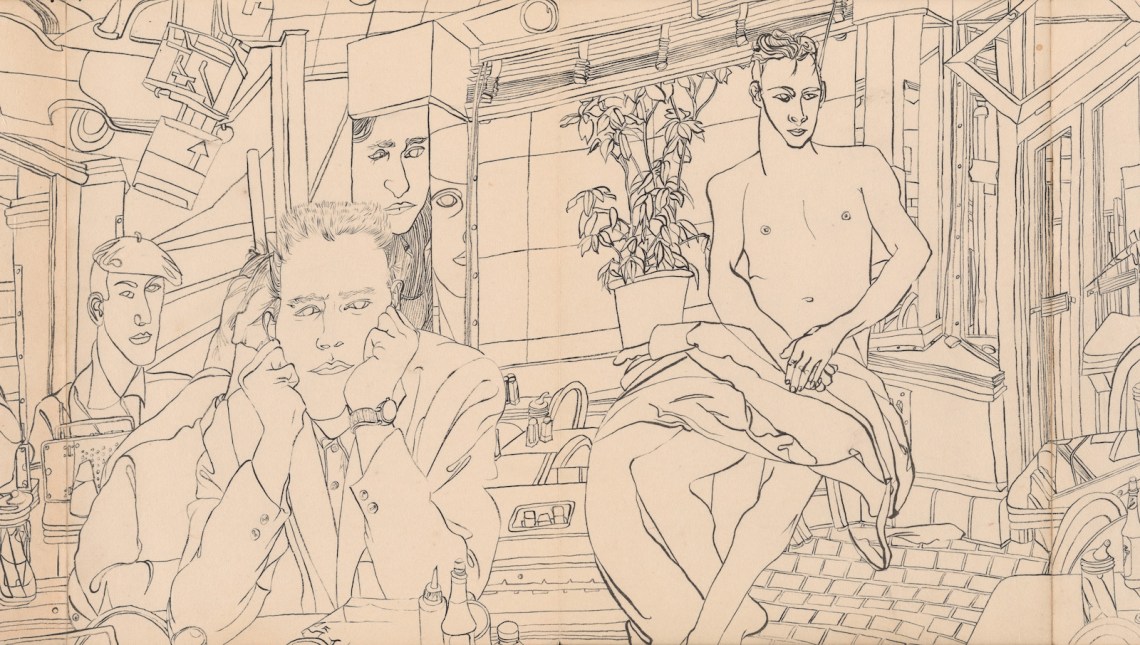

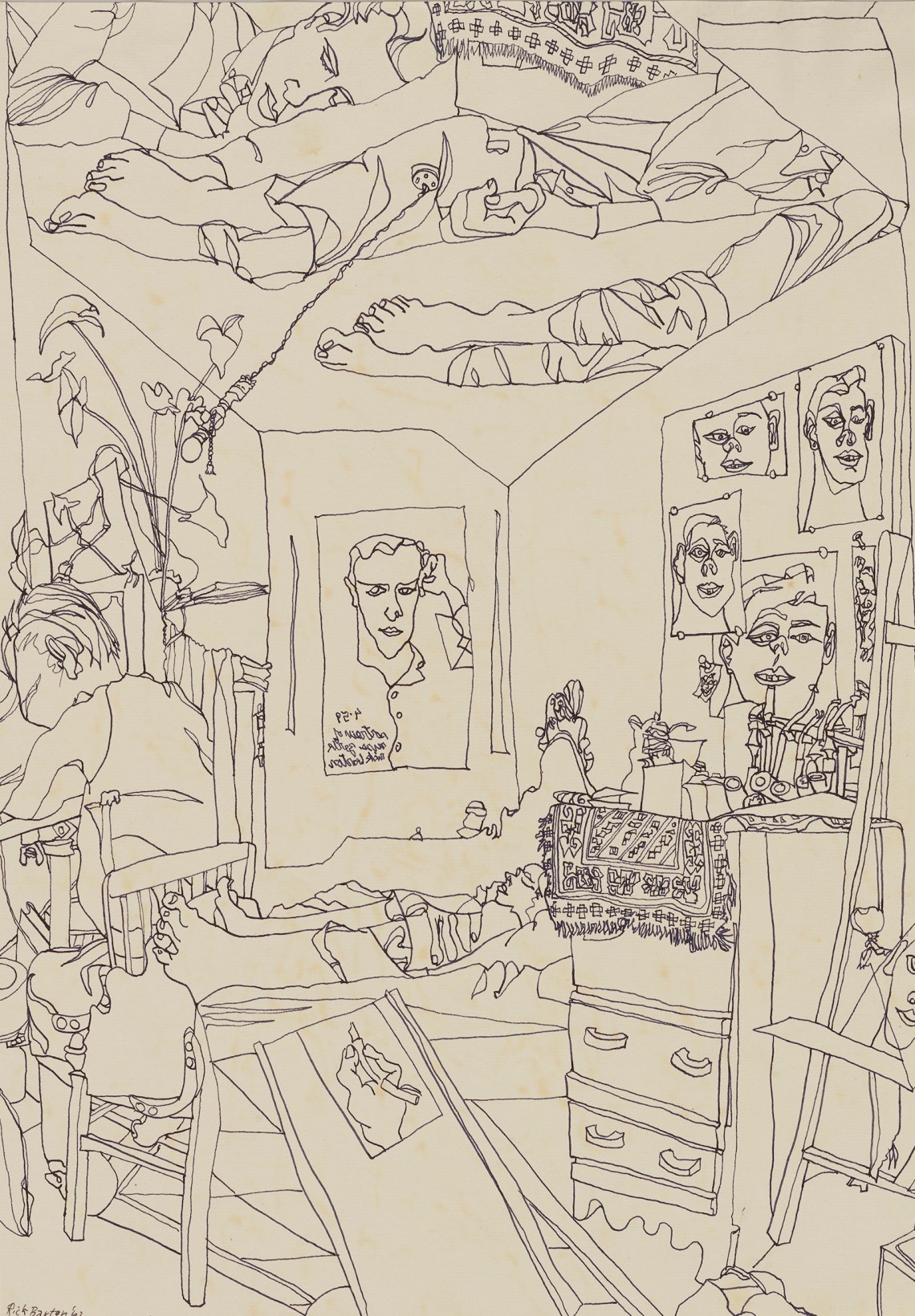

The show’s centerpiece and raison d’être, however, is a long vitrine containing a pair of extended leporellos. These large, illustrated books are not merely works of clever satire or virtuosic portraiture—although they are that, too—but also highly original narrative structures that play with time and space. In these series, we trace the faces and torsos of varied visitors to cafés where Barton, too, is apparently seated, sketching. Stylized contemplative men appear as relatively empty subjects in contrast to busily delineated bookshelves, chandeliers, wooden and mirrored surfaces, birdcages, cityscapes, signage, twining plants and plumes of smoke, table settings, hardware, rickety furnishings. The changing scene that Barton would have recorded over many hours appears as a long, slow camera pan with a surrealist sense of perspective and scale. Time seems to have been flattened and dragged across the folds of the leporello in an extraordinary feat of draftsmanship.

The phrase “writing a chrysanthemum” captures how fluidly Barton moved between graphical and lexical modes. His inked line enters only playfully, provisionally, into the task of fashioning figures and refuses to commit fully to the illusion of three-dimensional space. Like an oiled thread or a sinuous, glinting extension cord, it is supple but never subordinate to the representation of a given form. There is a resplendent frankness to this line that feels verbal, as if it wants to speak, not show; exclaim or even scream, not delineate. The simultaneous whimsy and emotional agony of Rick Barton’s style is not to be missed—its insoluble complexity, indefatigability, and humor is a balm for anyone who has begun to wonder if we are living in the worst of times. Barton, who struggled with addiction and was frequently persecuted for his sexuality, has wisdom to share. He wants us to know that the eye of the beholder is an unstable site in which terror and pessimism can unpredictably change places with a sharp, deep joy.