In the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley, California there is a 1988 letter from Ferdinand Marcos Sr. begging Reagan to intervene in the racketeering and fraud case that Rudy Giuliani, then the attorney for the Southern District of New York, was pressing against him and his wife Imelda in US Federal Court. “I remain your obedient servant,” Marcos signs off, invoking the long colonial relationship between the US and the Philippines. Reagan declined, no doubt because the US had already shifted its support from Marcos to his successor, Corazon Aquino. He would, he said, rather let the lawyers do their work and the judicial process take its course. Sick with lupus and exiled in Honolulu after being overthrown in 1986 by a civilian-backed coup, Marcos was at the nadir of his career. By September 1989 he would be dead.

Ever since their downfall, the Marcoses had plotted their return in earnest. News stories and FBI files detail their failed efforts to secure weapons and overthrow the Aquino government. By the 1990s, however, the family’s fortunes began to turn. Imelda was put on trial in Manhattan and acquitted in July 1990. The following year she and her family were allowed to return to the Philippines by President Aquino and her successor, Marcos’s cousin Fidel V. Ramos, on the condition that the family would surrender at least some of the billions they had plundered from state coffers. They never did. Rather, the next three decades saw the steady recovery and rehabilitation of the Marcoses’ reputations in the country.

After returning to the public eye with two failed runs for the presidency, Imelda settled for representing the congressional district of her husband’s hometown in Ilocos Norte. Her eldest daughter Imee and son Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. took turns as governor and congressional representative of their province, then as senators. Bongbong ran for vice president in 2016 but lost to then representative Leni Robredo. He refused to concede and demanded recount after recount, each of which he lost. But his claims meant that he remained, like his mother and sister, publicly visible as the aggrieved party cheated out of his rightful victory.

Later that year, despite vigorous protests from the victims of martial law, President Rodrigo Duterte allowed the burial of Marcos’s corpse at the National Hero’s Cemetery in Manila. The culmination of the family’s comeback was Bongbong’s landslide victory in the presidential elections this May, which returns the Marcoses to the summit of political power. Bongbong’s twenty-eight-year-old son, Sandro, now occupies the congressional seat that belonged to the family like an old home, auguring the continuation of the dynasty well into the next generation.

How did this happen? What accounts for the Marcoses’ return? Many observers have noted that, since 2009, Bongbong has used an army of vloggers and social media influencers to drastically revise the history of his father’s rule, redrawing the years of martial law as a “golden age” and Marcos Sr. as the “best president” the country has ever had. YouTube and TikTok videos depicted the Marcoses as a normal and unpretentious bourgeois family: in one, Bongbong said that he decided to run for the presidency while streaming Ant-Man with one of his sons. He studiously avoided interviews and debates, making it impossible to hold him accountable for his family’s depredations and question his plans for the future. Instead of Duterte’s aggressive persona, he projected a more benign figure who sought “unity” and a return to “prosperity,” eager to please and care for people rather than kill them. At the same time, Bongbong’s troll army mercilessly attacked his opponents, spreading rumors and all sorts of vile misinformation about their families and even threatening violence.

Other factors helped account for Bongbong’s success. With Sara Duterte, President Duterte’s daughter, as his vice president, Bongbong offered continuity with what had been a popular regime, even as he distanced himself from its violent drug war. The Marcos family’s billions were most likely used to buy votes and the support of local officials. The opposition was relatively weak: lacking in resources and ideas, and unable to form coalitions, they failed to attract a sufficient following. The most promising challenge came from Leni Robredo, who was at first hesitant to run; despite a late surge, she fell woefully behind the Marcos-Duterte tandem. But Bongbong’s landslide victory has also been decades in the making. Indeed, the return of the Marcoses is difficult to understand without considering the history of what scholars like Ruby Paredes and Michael Cullinane have called “colonial democracy” in Philippine politics.

*

The Philippine nation-state is an imperial artifact. Waves of colonial domination—by the Spanish starting in the late sixteenth century, the United States from 1899 to 1941, the Japanese from 1942 to 1945, US neocolonial rule through the cold war and beyond, and now the looming influence of China—have decisively shaped the country’s political economy, social structure, and culture. Recurring acts of resistance in the form of local rebellions, Muslim uprisings, anticolonial revolution, guerilla warfare, communist-led peasant revolts, workers’ strikes, failed military coups, and civil society protests punctuate this history of colonial hegemony.

Advertisement

Each colonial power looked for ways to contain such resistance: Catholic conversion under Spain (close to 80 percent of the population today remains Catholic), public education under the US (American English remains one of the official languages and one of the most widely understood in the country, and the US continues to be regarded with affection and trust by the majority of the population), militant anti-Western nationalism under Japan (anti-US sympathies remain strong among radical nationalists), and anticommunism under the pressure of the US during the cold war (despite waging a fifty-year Maoist insurgency, the longest in the world, the Communist Party of the Philippines remains a relative outlier in the country’s politics). But colonial governments’ attempts to shape the conduct of their subjects only inspired new forms of resistance—dissent, rebellions, fugitivism, sabotage—that put their power and legitimacy back in question. This dialectic of domination and resistance, not surprisingly, made for a persistent crisis of authority.

One of the most important means for resolving this chronic crisis of colonial authority was elections. Beginning in the Spanish period, elections were introduced to secure the support first of prominent village heads (datus) and, later, landowners and entrepreneurs who had benefitted from the agricultural and commercial revolution of the nineteenth century. They came to make up the upper class of native society, the principalia. Exempted from tribute and forced labor (both of which they were required to collect from natives), local elites were allowed to choose among themselves who would occupy the lowest rung of the colonial bureaucracy as village headmen and municipal governors. These elections were subject to the approval of the Spanish governor-general and the veto power of the parish priest.

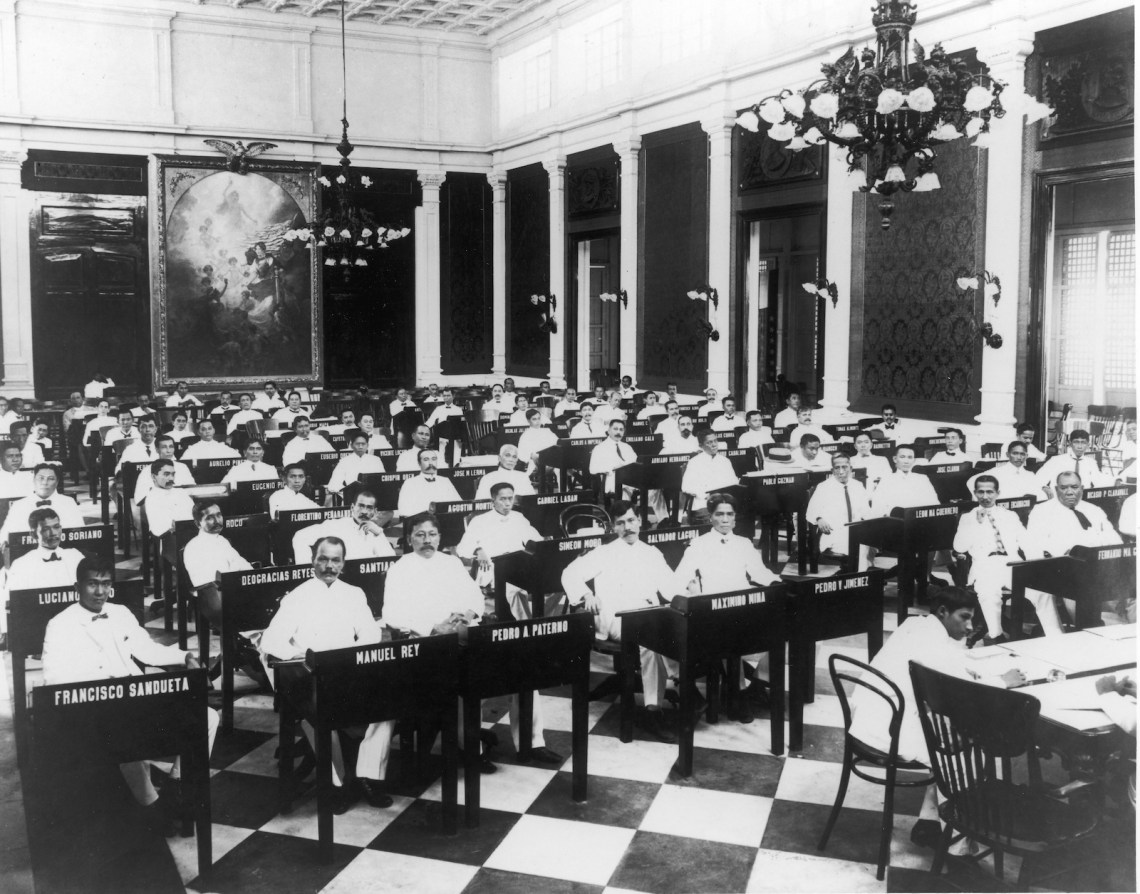

During both the Revolution of 1896 against Spain and the First Republic of 1899, which soon went to war against the US, elections were held among the Revolutionary and Republican leaders to organize a postcolonial society under provincial elites, most of whom self-consciously referred to themselves as an “oligarchy of the intellect.” These leaders sought regime change, eventually defeating Spain and resisting the US in a brutal guerilla war. But they were also anxious to fend off a social revolution from below stirred by the very anticolonial movements they had led, which drove them to collaborate with the US (and later, Japan) to suppress threats to their authority. Capitalizing on this fear of social revolution among the Filipino elites, the US offered them electoral means for securing their local bases of power. In the first local elections of 1902, then in the national election for the colonial assembly in 1907, the US colonial administrators limited the franchise to property-owning men fluent in either Spanish or English—fewer than two percent of the population. Elections were thus a way of orchestrating collaboration and counter-insurgency.

The franchise was gradually expanded in the 1930s as elite women won the vote, and in the aftermath of independence in 1946, the Second Republic instituted universal suffrage. On the one hand, elections in this postindependence period made social change possible by giving everyone the right to vote. The poor were politically empowered even as they continued to be economically and socially marginalized. On the other hand, elections also gave rise to extensive corruption, vote-buying, and vigilante violence on the part of powerful families seeking to win office. Elections became vehicles for promoting political dynasties, since only the wealthy had the means to run expensive campaigns. They also encouraged illicit activities such as smuggling, illegal gambling, drug dealing, extortion, and outright stealing from state coffers. In other words, they were popular democratic means that more often than not created undemocratic social effects, propping up what in effect was an oligarchic autocracy.

It was under the contradictory conditions generated by colonial democracy in a postcolonial era that Ferdinand Marcos Sr. managed to win his first presidential term in 1965 and reelection in 1969. He sought to resolve the country’s crisis of authority once and for all by declaring martial law in 1972. Instead, he intensified it. Marcos ruled by decree, replacing Congress with a rubber-stamp parliament and installing a compliant judiciary. He rewrote the constitution to extend his tenure and did away with checks and balances. He expanded the military and the police to brutally suppress his left-wing critics and quash the private armies of rival oligarchs, whose properties and businesses he confiscated and redistributed to his family and cronies. Imprisonment, censorship, torture, and extrajudicial killings meted out to his opponents became the hallmark of his regime. Marcos also set about systematically looting the country, redirecting loans and foreign aid to his family’s pockets. He demanded substantial shares in every major business deal, depositing billions in Swiss and overseas bank accounts and buying up real estate in the United States and elsewhere to stay liquid.

Advertisement

Meanwhile, Imelda set about constructing the cultural scaffolding that would give the regime its sheen of authoritarian modernity. She commissioned buildings done in brutalist style—the joke then was that she had an “edifice complex”—to host lavish film festivals, Bolshoi ballet performances, classical music concerts, and Miss Universe beauty pageants. The couple’s propaganda machine transfigured them into “Malakas” and “Maganda,” the mythical first people of the Philippines, depicted emerging from bamboo stalks on the walls of the presidential palace. In Imelda’s personal chapel, a large gilded mirror appeared on the altar, reflecting her image as she prayed. The excesses of Imelda and her family were the stuff of legend: aside from the thousands of shoes, she would order the closure of entire department stores for the day while she dropped millions of dollars on jewelry and clothes. She avidly collected European masterpieces worth hundreds of millions and purchased New York, New Jersey, Hawai’i and California real estate, including the Crown Building, Herald Center, and the former estate of Charlie Chaplin. She would throw hundred-dollar bills into the air in her hotel suite and watch in amusement as her coterie of “blue ladies”—socialites who accompanied her on her diplomatic trips—scampered on the floor to grab the money.

Eventually, the crimes of the Marcoses would catch up with them. By the early 1980s, the economy had undergone a severe contraction, the country’s debt had risen to unsustainable levels, and over a third of the population lived below the poverty line, forcing thousands to seek employment abroad. Resistance to Marcos’s rule intensified, especially after the dramatic assassination of his chief rival, Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino, on the airport tarmac as he returned from his exile in Boston in 1983. The Communist Party grew rapidly, especially in the countryside, as did the Muslim separatist movement in the South, while opposition from the Catholic clergy became more pronounced. There also emerged a well-organized anti-Marcos solidarity movement both in the Philippines and abroad, joined by US senators and congressmen who decried Marcos’s thievery and human rights violations. Worse, the Pentagon started to sound the alarm about the waning ability of the Marcos administration to safeguard American bases in the face of left-wing challenges.

Confronted with this crisis, Marcos went on American TV and called a snap election for February 1986 to prove his enduring popularity. In doing so, he inadvertently mobilized the very forces he sought to contain: civil society groups opposed to his rule put forth Ninoy’s widow, Corazon Aquino, as their presidential candidate. Electoral observers came from the United States and other countries, trailed by the international media, to expose Marcos’s corruption. His strategy to consolidate power through the ballot had backfired: the elections became an international spectacle and proved to be the dictator’s undoing. As Marcos declared victory, forces loyal to Aquino rejected his claim and joined elements of the military in a coup, gathering for four days at EDSA, one of Manila’s main thoroughfares, to call for his overthrow. Finally the US, now anxious to dispense with an unreliable client, provided helicopters to take the family away from the palace, transport them to Guam, and eventually deposit them in Honolulu. Corazon Aquino took her oath of office, inaugurating the post-Marcos era—or rather, from the perspective of recent events, the beginning of the Marcoses’ protracted return.

*

The overthrow of the Marcoses was accompanied by popular expectations for social change, many of which were reflected in the 1987 constitution. But after a brief period of democratic debate and reform, regime change, as in the past, was followed by the restoration of elite rule. Coming from the old oligarchy, members of the Aquino government enacted neoliberal reforms that benefited mainly the wealthy as well as some sectors of the middle class, further amplifying the great inequality between rich and poor. As in many other parts of the world, the rural and indigenous population suffered the most, often left unprotected from the frequent natural disasters that visit the archipelago. Patterns of dispossession and displacement continued: many were forced to migrate to the cities, swelling the population in the slums and sharpening the sense of precarity among their inhabitants. Food insecurity remained acute and unemployment and contractual employment spread further, driving those who could to seek jobs overseas. Illicit activities, from drug dealing to illegal gambling, became even more widespread. In the face of continuing communist and Muslim insurgencies, violent right-wing militias and vigilante groups mushroomed. Supported by the military with the approval of the Aquino administration, they spread terror and wreaked havoc, especially in rural areas. Beset by a series of coup attempts and military demands to end negotiations with the Communists, the Aquino government resumed arresting and torturing left-wing dissidents just as the Marcos regime had.

The so-called EDSA Republic lunged from crisis to crisis. In a farcical repetition of recent history, a later president, Joseph “Erap” Estrada, was overthrown by a popular uprising known as EDSA II in January 2001, barely two years into his tenure. He had been charged with gross corruption and was deeply despised by the “respectable” members of the oligarchy for his populist crassness. Try as they might, reformist presidents such as Fidel V. Ramos, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, and Corazon’s son, Benigno “PNoy” Aquino, could not do enough to address the rising discontent of the people.

Duterte’s campaign in 2016 seemed to his supporters to offer a solution to the failures of oligarchic rule. He promised to solve what he considered the country’s most pressing problem: the scourge of drugs, particularly crystal methamphetamine, known as shabu in the Philippines. Empowering the police and vigilantes, Duterte launched a bloody drug war that targeted poor communities. The progress of the war was measured in the harvest of corpses that appeared nightly on street corners, walkways, and under bridges. Duterte regarded drug users and dealers—he made no distinction between the two—as social enemies who threatened the very existence of the nation. Just as colonial authorities sought to execute insurgents who threatened their rule, so Duterte’s policy of summary executions was no less than the continuation of a counterinsurgent war.

Many of Duterte’s promises went unmet. The drug war did not result in any appreciable decrease in drug use or the prosecution of any major drug lord; corruption, especially in the midst of the Covid pandemic, became even more blatant; political dynasties and oligarchic rule expanded. And yet Duterte’s murderous bluster, misogynistic rants, and unremitting drug war continued to prove popular among an electorate searching for a strongman to deliver quick solutions to deeply rooted problems. He ended his presidency with an impressive 73-percent approval rating.

*

Bongbong’s level of popular support—like Duterte’s—cannot be explained simply by social media disinformation or sheer coercion. Is there something else in Philippine political culture, shaped as it is by this history of colonial democracy, that favors authoritarianism and oligarchic domination? One answer can be found in the systems of patronage that have long mediated power relations in the Philippines. For example, in his letter to Reagan, Marcos Sr. positions himself as a client appealing to his patron for aid—a relationship of subservience deriving from the long history of colonial rule. Elite collaboration with colonial rulers was built on a shared desire for mutual dependency between rulers and ruled: colonial authorities needed local elites to consolidate their power with labor, favors, votes, and political muscle just as elites looked to the colonial state to secure and expand their positions of privilege by giving them money, jobs, food, or military and legal protection. From the Philippine perspective, these patron-client ties followed a moral economy of deference, or hiya (literally “shame”), and reciprocal obligations, utang na loob (“debt from the inside”).

At the same time, patronage provides an idiom for articulating demands from below. In a predominantly Christian country like the Philippines, clients of whatever social class have traditionally called upon those in power to live up to their obligations using the language of prayer and ritual acts of charity: peasants expecting landlords to provide them with aid during times of hardship; workers asking bosses to give them higher wages; domestics requesting money to take care of sick relatives; debtors seeking forgiveness for their loans from creditors; voters asking politicians for jobs in exchange for their votes. The dictator, for his part, acts as the client of powerful patrons like the US and China even as he extends his patronage over the masses of the country’s people. These patron-client ties, bound by reciprocal obligations but also prone to disruption, reinforce social hierarchy and ongoing inequality between the two parties, narrowing the chances for popular democracy.

Under such unstable conditions, it is not difficult to imagine how patronage politics can cultivate the ground for the emergence of authoritarian rule. Amid actual and perceived disasters, they tend to generate the desire among both patrons and clients for a benevolent—and patriarchal—dictator who promises order, material comfort, and cultural meaning. But they can also produce periodic tensions, since patrons are prone to neglect or exploit their clients and fail to deliver on their promises. Crisis is thus an integral part of the patron-client relationship that in the Philippines defined both colonial domination and postcolonial oligarchic rule. Those who deviate from the relationship’s terms—socialists, feminists, trade unions, critical journalists, artists, and activists—are either coopted or targeted for harassment, censorship, and persecution. This political culture has precolonial precedents, but its modern workings grew out of colonialism and counterinsurgency. Any meaningful opposition movement in the future will have to contend with its structural features and historical force.

Judging from his cabinet appointments, Bongbong will most likely continue many of Duterte’s policies and those of his predecessors: the neoliberalization of the economy, the rule of oligarchs, the appointment of cronies alongside compliant technocrats, systematic graft, censorship of the media, the red-tagging of critics, and the continuation—however attenuated—of the drug war through police impunity. With Sara Duterte as vice president, the administration will undoubtedly insulate Duterte from the International Criminal Court investigations into his human rights record as well as resist any attempt to seize the Marcos family’s assets. But the tone will change in accordance with the cosmopolitan upbringing of Bongbong and those around him. Duterte was stridently hostile toward the US and the EU for their criticisms of his human rights record and fawned on China, which applauded both his strongman rule and his willingness to let it control large sections of the South China Sea. Bongbong seems poised to be more conciliatory with the foreign powers whose aid he needs, and early signs indicate that he will be less compliant with Chinese assertions of sovereignty over the South China Sea. Compared to Duterte, he likely will make fewer blatantly sexist remarks, given his mother and wife’s considerable influence over him, and far less provocative statements about crime and criminality.

In short, Bongbong offers a more mellow authoritarianism—one many Western powers, including the US, will find tolerable—even as he leaves the more virulent attacks to his lesser deputies. Judging from the last elections, counter-hegemonic forces both in the Philippines and in the diaspora, such as the reformist “pink” movement of Leni Robredo, have fallen far short of contesting the patronage-driven practices of oligarchic authoritarianism. But given the country’s history of resistance movements and the conditions of generalized precarity that cut across all social classes, the new administration will have to deal with what amounts to a state of permanent crisis that is bound to mobilize new forces and present possibilities for change.