In her memoir Self-Portrait (2019), Celia Paul describes being baffled by the prospect of life-drawing classes when she first arrived at the Slade. “It seemed so artificial to me to draw a person one didn’t know or have any involvement with,” she writes. “I needed to work from someone who mattered to me.” Paul’s stress on the particular affinity between portraitist and subject—and her discomfort with that relationship made impersonal—reminded me of a confession Maeve Gilmore makes in A World Away (1970), her account of life with her husband, the artist and writer Mervyn Peake, famous for his Gormenghast books, one of the most lauded Gothic fantasy series ever written. In 1938, a year into their marriage, the first drawing Peake sold at his debut solo show was of his wife. It felt to Gilmore like a violation, as if her actual body were being traded: “It seemed inconceivable that a drawing, made alone and imperatively, should go to a house of strangers, hang on their walls, and be looked at, liked or disliked, spoken of by people we didn’t know or care about.”

Paul is speaking from the point of view of the artist, and Gilmore of the sitter, but Gilmore was an artist, too. Although they lived forty years apart, the parallels between these two young British women are uncanny. Both arrived at art school as excruciatingly shy teenagers from strong religious backgrounds—at seventeen, Gilmore was a “convent-reared girl, with a built-in nervousness,” so full of inhibitions it took her half an hour just to enter the classroom—and each found herself immediately in thrall to an older male artist who also happened to be her teacher, Paul with Lucian Freud and Gilmore with Peake. Twenty-five years old, with dark hair and eyes, he was, Gilmore remembered, the most romantic-looking man she had ever seen. The attraction between them was instantaneous, and they married the following year.

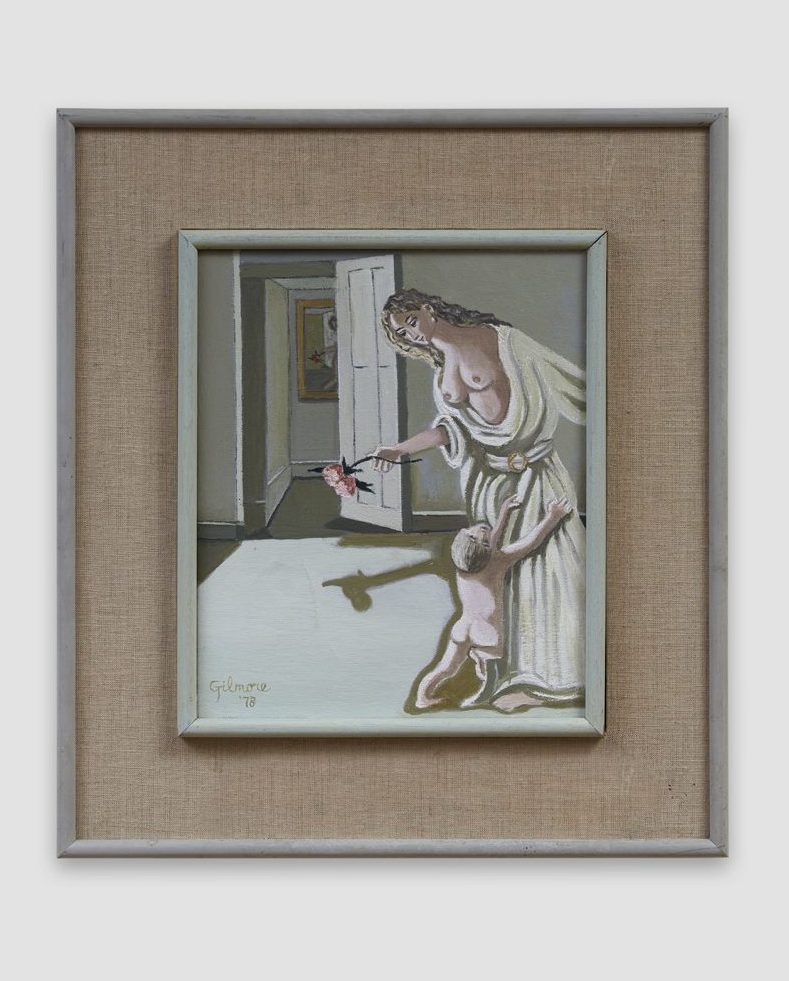

This is where Paul’s and Gilmore’s paths diverge. Paul felt claustrophobic sitting for Freud, resentful of the time it took away from her own painting. When their son was born, she firmly disengaged from the day-to-day demands of motherhood, refusing to participate in conventional domestic drudgery. Her Bloomsbury studio, where she still lives and works alone today, has always been a retreat from the wider world. Gilmore’s “cocoon,” by contrast, wasn’t complete without the presence of her beloved husband and their three children.

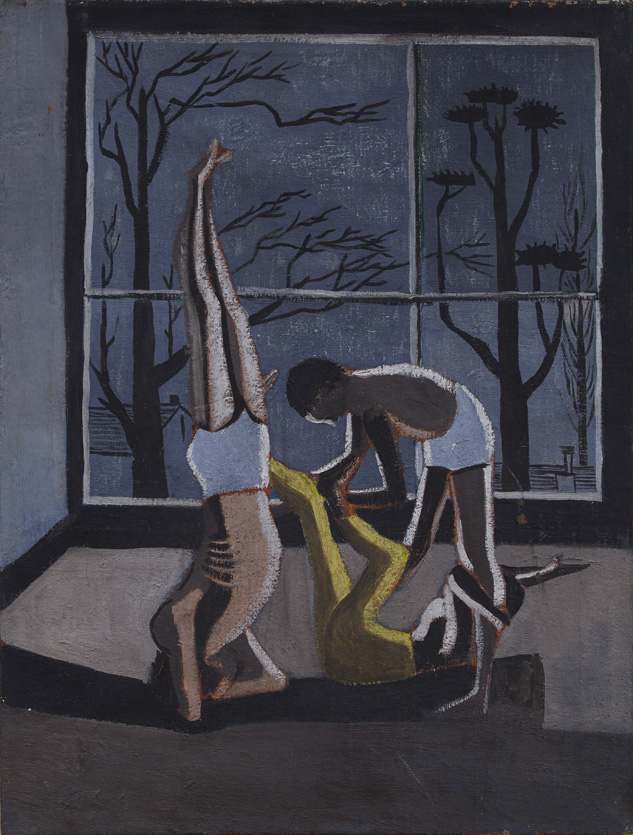

It’s this strong sense of familial, rather than individual, isolation that comes across in the twenty paintings currently on display at Studio Voltaire in London, the first institutional solo exhibition of Gilmore’s art. In Le Châlet, Sark (1973), the large, ugly house the family lived in during their three-year residence in the Channel Islands in the late 1940s is set against a brooding gray sky. Three lone figures stand in the foreground: Gilmore and her two sons, their feet deep in the long grass as if they’re being swallowed up by the wild, untamed garden. In Acrobatic Children at Night (c. 1958), the tumbling, scantily clad children—all long limbs, taut ribcages, and gaunt shadows—are portentously framed by a floor-to-ceiling window, through which loom the black silhouettes of bare-branched trees, ominous and threatening. The children inside are oblivious and safe.

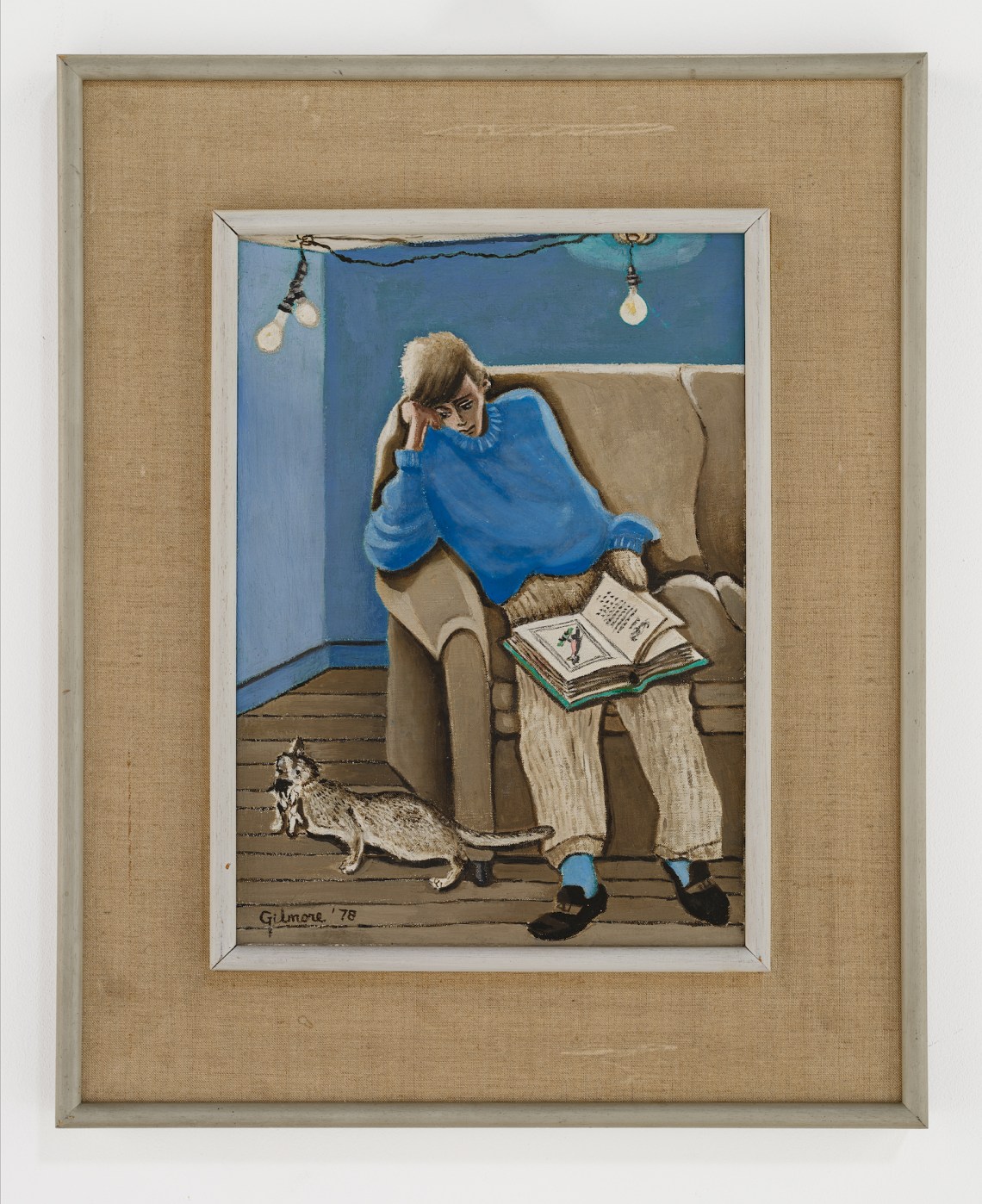

Windows feature often in Gilmore’s work, and she always paints them from the inside looking out, the demarcation of a threshold to a more dangerous world. But there’s also something unsettling about her interiors, all but stripped of the usual connotations of comfort, occupied by either furniture or figures but seldom both. The only exception in the show is Boy Reading (1978), a small oil painting of a teenager sitting on a sofa. There’s an open book lying in his lap, but he’s distracted, looking at the cat stretched out at his feet instead. Both creatures look at ease, but there’s nothing cozy about the scene. The striking blue of the boy’s jumper and socks, echoed in the icy pigmentation of the wall behind him, is the only splash of color amid a palate of grays. The floor is stripped wooden boards, and strung from the ceiling above are three bare, glaring lightbulbs. Stare at it long enough, and the room begins to look like something one might stumble into during a nightmare, or the site of an interrogation. The home may be a refuge, but it’s not an idyll.

Gilmore’s “blue-eyed thugs”—the nickname the poet Louis MacNeice gave her two eldest children, Sebastian and Fabian (already age nine and seven when their sister Clare was born, in 1949)—are the subjects of nearly half the paintings. Rarely traditionally posed, the boys are caught, almost as if unawares, deep in their own imaginative worlds. They “lived wild lives with us in our studio,” Gilmore writes in A World Away. “Mervyn would draw them at any moment, playing and fighting.”

Advertisement

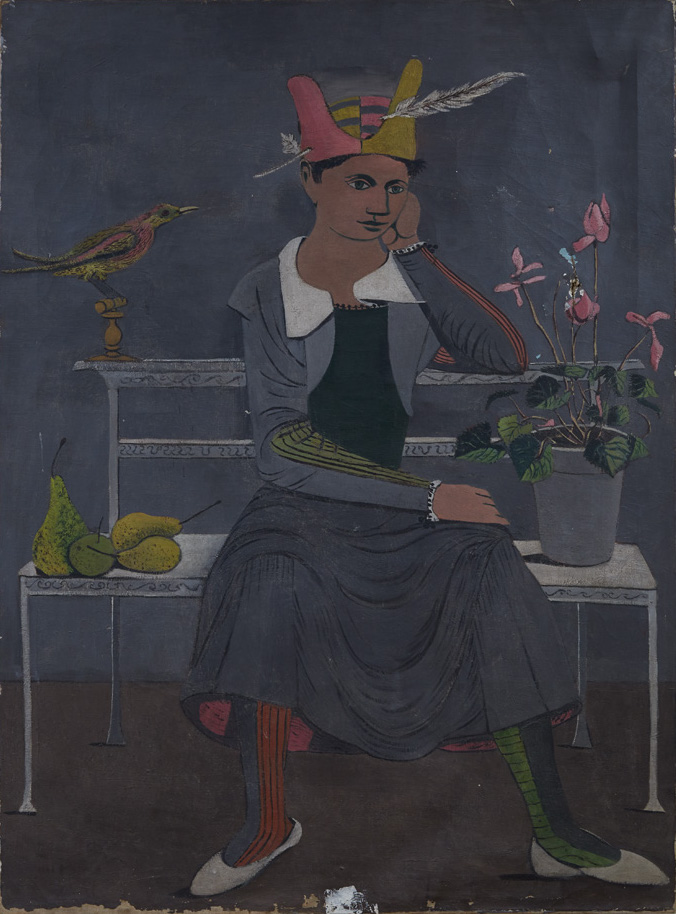

Her portraits are more studied than the firm but spare pen-and-ink sketches that Peake doodled around the margins of his manuscripts, but they still give a sense of animation and movement, of lives being lived. The child in Boy in Window (c. 1956) looks only momentarily suspended, one hand leaning on the open sash, the other holding back the curtain, a leg arched out of view. The drooping white feather of his Native American headdress flops down over the pane, and the green tendrils of two sprouting onions discarded on the windowsill reach aloft, a clear line of vigor that courses up through the canvas. There is quietness and absorption here, even as childish fantasies of colonial warfare provide a whisper of latent violence. Two Boys, Cat’s Cradle (c. 1952), meanwhile, is an angular, almost Cubist composition. The sharp lines of the strings that bind the four hands together, which form a pyramid that draws one’s eye to the center of the painting, are echoed in the crisp outlines of the boys’ clothes. Their single-minded focus is reflected in the opaque black background. For the duration of the game, at least, nothing else matters.

*

It’s tempting to think of Gilmore as yet another female artist subordinated to her husband’s career or exploited as his muse. She did exhibit early on, in the 1930s, but as marriage and motherhood forced her attentions inward, her work adapted accordingly. Not only were her family and their home life the great themes of her painting, but she used the domestic environment itself as a canvas. In one of the family’s London homes, she adorned the wall along the staircase that led up to her studio with pirouetting ballet dancers and painted every surface of the kitchen with intricate, colorful murals featuring animals, figures, and woodland scenes. These, of course, were never seen by the public, nor were they ever meant to be. Indeed, until now, if Gilmore has been known at all it has been as keeper of her husband’s flame.

Peake’s work supported his family. He had already exhibited at the Royal Academy and other galleries before he met Gilmore, and from the late 1930s was much in demand as a book illustrator. When World War II broke out he was keen to serve his country the best way he knew how, immediately volunteering his services as a war artist. Though he applied several times, he was turned down and instead conscripted into the army. Ill-equipped for a life of military discipline, he suffered a nervous breakdown in the spring of 1942 and was hospitalized for six months. Through it all, Gilmore provided him with emotional and practical support. Following Peake’s discharge from the army he began writing in earnest, and always shared his drafts with her. She was his first reader on Titus Groan (1946), the first Gormenghast novel. After Peake’s death from early onset dementia in 1968, she finished the last installment of the series using notes he had left behind. It would be wrong, though, to interpret Gilmore’s story as one of personal artistic frustration. “I always seem to have been able to paint when there is intense life surrounding me, despite the eternal meals, the fights of one’s children, and the constant demands of domesticity,” she writes with agonizing honesty in her memoir. “It is now, with more time and less friction, that I find it harder. I miss Mervyn.”

Sark Interior (c. 1947)—an empty room looking out onto a moonlit landing with a painting of a dead tree on the wall, a few sprigs of flowers in a glass of water on a table, and the family cat curled up in a discarded newspaper in the doorway—is reminiscent of Dorothea Tanning’s dreamlike hallways or Leonora Carrington’s uncanny rooms. While the images are always drawn from real life, Gilmore uses carefully chosen objects with symbolic effect to achieve an atmosphere not quite of this world. But her surrealism is more grounded in the domestic than anything either Tanning or Carrington painted. It’s her richest subject, and the site in which she appears to have been most comfortable.

I wish the exhibition had included a particularly astonishing self-portrait that Gilmore painted in 1978, in which she stands proudly bare-breasted in a dark room, framed by the open doorway, her arms held high above her head. It’s strongly reminiscent of Tanning’s self-portrait Birthday (1942), right down to the inclusion of a small animal, like a witch’s familiar, front and center in the scene—though Tanning’s is a mythical bat-like creature with the wings of a hawk and sharp clawed feet, while Gilmore’s is the family cat. Like so many of Gilmore’s paintings, it’s a scene both deeply grounded in reality—there are three saucepans lined up on a shelf in the foreground and a kitchen sieve hanging from a hook on the wall—but one that might, on first glance, just as well belong in a fairy tale. Consider also the soft eeriness of the blue-eyed thugs sitting calmly side-by-side in Boys in Orchard (c. 1954), a cat cradled between them. The ground is littered with fruit, but the light is darkly foreboding and the trees are gaunt and spindly. Gilmore loved to paint the trees on Sark, “warped by the wind into strange, grotesque and sometimes ghostly shapes.” She was drawn, she said, to their sinister, almost spectral “loneliness.”

Advertisement

The dark skies, stark trees, and inauspicious shadows might best be interpreted as the various demons with which Gilmore lived: Peake’s mental illness, then his progressively debilitating physical symptoms as the dementia took hold. This was the reality of their life together. Ultimately, Gilmore’s paintings are an intimate record of that reality, down to the chipped and worn edges of the canvases that have hung not on gallery or museum walls but in family homes. All but two on display still belong to the Gilmore estate, which one suspects is what the artist herself—once so disturbed by the idea of her own portrait, painted by the man she loved and who loved her, hanging on a stranger’s wall—would have wanted. “What is made in silence, out of passion and craftsmanship,” she writes, “should not be displayed until long after the passion has died away.”