A sudden bang erupts in the opening moments of Memoria, as if volleyed from the edge of a dream. It rouses Jessica (Tilda Swinton), a Scottish orchidologist far from home and suffering the insomniac’s usual fog: night drips into day and hallucinations leak into waking life. Like the ghosts and monsters that the filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul has previously lured from the forests of his native northeastern Thailand, the sound in Memoria, his latest feature, is both spectral and terrestrial. At times it seems a phantom audible only to Jessica; at others, an emanation from the landscape. As we drift through central Colombia, from Bogotá to the rural village of Pijao, the mystery of the sound’s origin gives way to that of its course: how it moves through Jessica and moves her through more than just this world.

That opening bang is an offscreen sound, cleaved from any visible source. The search for its cause, though, involves not just the ear but all its fellow senses. “What was that sound?” is another way of asking: What do I know about the material world and how it behaves? Memoria’s sound design nudges prosaic scraps of ambient noise into the spotlight: a chair’s metallic shriek as it scrapes across the floor; blaring car alarms in a dark parking lot; the percussive drone of unrelenting rain. A backfiring bus becomes the crux of an early scene when Jessica watches, in broad daylight, as a man hears the blast and flings himself to the ground at a busy crossing. When he clocks the explosion’s pedestrian source, he leaps into a sprint anyway, as though the false echo of a violent noise is as true as its memory. The camera stays with Jessica’s bewilderment, her face furrowed as if in recognition of another life unraveled by the troubling gap between hearing something and knowing what you really heard.

In pursuit of her own apocryphal sound, Jessica meets with a young sound engineer, Hernán (Juan Pablo Urrego), at his studio in a university’s music department. This is the first time she attempts to describe that early-morning bang; the need to give it a tangible form is also a need to share it in language. Hernán’s English is as shaky as Jessica’s Spanish, but he’s committed and attentive, building off her stilted approximations: “It’s like…a big ball of concrete falling into a metal well…surrounded by seawater.” She resorts to gestures, too, her hands sculpting the air to limn the ball’s size and movement, though each sound he plays in response to her prompts is slightly amiss. Finally, one articulation steers close: “It’s like a rumble from the core of the earth.” Hernán pulls up a folder of Foley effects—postproduction sounds made to mimic real-world noises—and imports a track, its frequency displayed onscreen as a multicolored waveform. “Look at this mountain,” he says, dragging his cursor and clipping its peak to round off the sound. Stunned by the near-perfect recreation, Jessica has no words.

The irony, of course, is that we have already heard this impossible sound and will have heard it over and over by the film’s close, no clumsy verbiage or gesticulation needed to conjure it. In an interview at last year’s New York Film Festival, Apichatpong told the novelist Katie Kitamura that the film’s soundscape was an “integration of the audience and Jessica,” the kind of shared listening that cinema makes possible. Like Jessica in Hernán’s studio, we are tasked with reassembling a memory—listening becomes a search, or a way of testing cause and effect. What might make a sound like this, and how might we seize its particular textures? We leave the studio with a collaged Foley track, traces of real, recorded sounds clipped and distended in the service of an unreal one.

It might be tempting to read the sound in Memoria as a metaphor in the narrowest sense—a scaled-up analogy or a cipher promising hidden meaning—but I prefer the poet Mary Ruefle’s definition: “If metaphor is not idle comparison, but an exchange of energy, an event, then it unites the world by its very premise—that things connect and exchange energy.” Over twenty years of multimedia work, Apichatpong has made people, places, and sometimes even the frame that holds them permeable to such exchanges. No surprise that the longest-standing motifs in his films are sleep and convalescence, two states that pry open the body’s borders. Since his clash with junta-imposed censorship following the 2006 military coup in Thailand, Apichatpong has mobilized both these motifs toward more pointed criticisms of state politics. In Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010), kidney failure becomes karmic retribution for a former soldier’s killings. Sleep itself is the sickness when, in Cemetery of Splendor (2015), two ancient kings and their warring phantoms cast a group of unsuspecting soldiers into narcolepsy.

Advertisement

In Memoria, Jessica’s insomnia has a counterpart in her sister’s hospitalization for a deep and strange fatigue. During a visit to the ward, Jessica befriends Agnes (Jeanne Balibar), an archaeologist studying human remains recently exhumed during the construction of a tunnel. In a sterile lab, we see technicians in white coats clean soil from calcic grooves while Agnes shows Jessica the jumbled skeleton of a young girl, likely six thousand years old, casually arrayed on a steel bench, its coarse texture in jarring relief against smooth metal. There is a hole in the skull—maybe a vestige of trepanation, Agnes suggests, inviting Jessica to feel it. She traces the missing bone with a rubber-gloved finger, hesitating, as if her touch might release something she cannot understand. Soon, Jessica confronts another mystery: when she returns to the studio in search of Hernán, there are no signs that he ever existed.

*

In September 2020, after fourteen years of work, Colombia opened the Túnel de la Línea, a highway tunnel that links Bogotá to the coastal port of Buenaventura. The passage was an infrastructural mega-project with no parallel in the region, its long-touted convenience of a piece with the government’s rhetoric of economic progress. But what President Iván Duque called “the dream of an entire country” also devastated the environment through which it cut: along La Línea’s 5.4 mile run, punched through the central Andean range, there has been water contamination and pollution severe enough to shut down a nearby school. Memoria contains a few shots of the tunnel’s construction, frames of a gaping, subterranean maw filled with hard-hat workers and bulldozers tearing through earth.

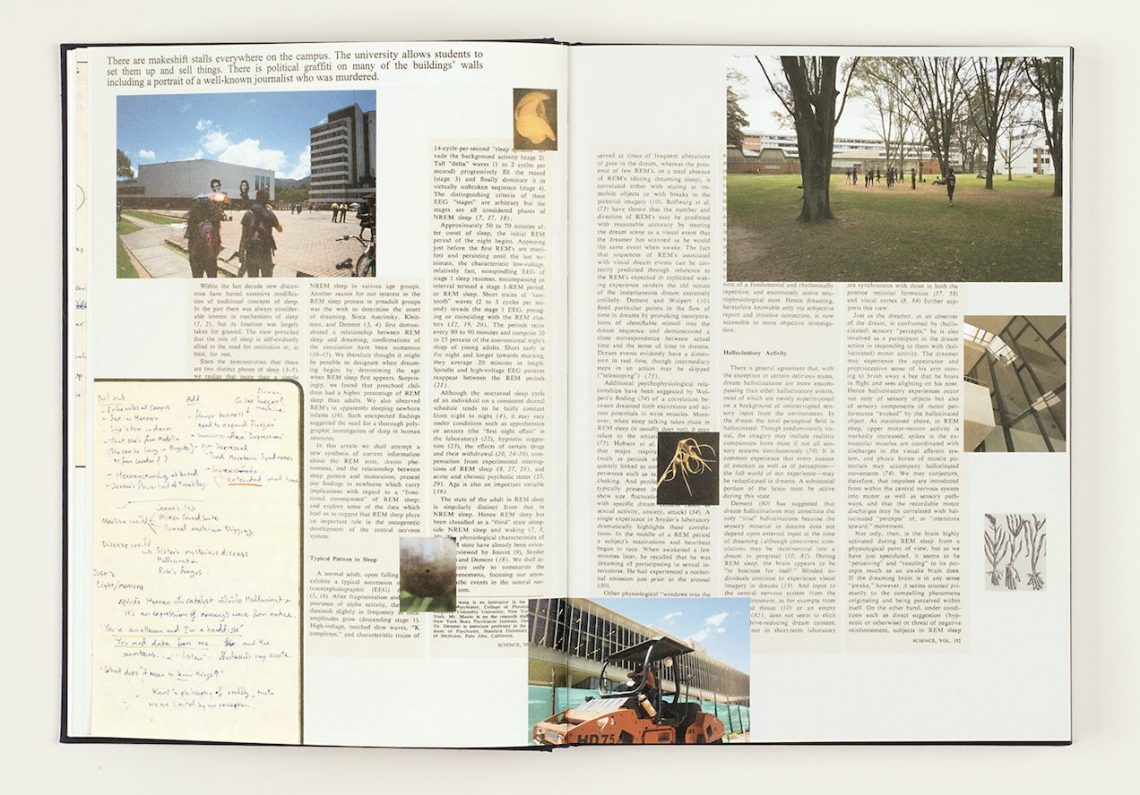

La Línea itself is never mentioned by name in Memoria, but the history of its construction is addressed in an artist’s book that documents the film’s production, published last year by Fireflies Press. A stunning collage of Apichatpong’s creative process, the volume gathers on-set photographs, research notes, and shooting script annotations. Its visual flow—not a single page number—complements the film’s own suggestive collections. A hollowed-out mountain pass and a hole in a trepanned skull; a vanished young man and a much older one who emerges from the ether, sharing his name; two white women summoned to Colombia, in part for their expertise in native biomatter: these sly doublings are everywhere in Memoria but strewn gently enough to feel like coincidence, which in Apichatpong’s work is always by design.

In its first half, Memoria’s elliptical structure comes to seem like a counterpoint to its many scenes of empirical research. Early on, we see Jessica in a library leafing through magnified pictures of orchids pocked with disease; on the way to Hernán’s studio, we glimpse a lecture on the making of stringed instruments and the absorbent properties of wood. Then there’s the archaeology lab, filled with forensic specialists trained to transform old bones into statements of historical fact. Jessica’s own research depends on preservation’s promise of permanence: when she visits a refrigerator manufacturer’s warehouse looking for a cooler in which to store orchid specimens, the saleswoman explains one model’s specialist tech, all coated alloys and pathogen filtration devices, but what she really extols is its ability to freeze time. Over the course of Memoria Jessica pursues the kind of containment that the film refuses in its very form, punctured as it is by so many narrative omissions that sounds and images move through it like wind through a net.

This tension seems to echo Apichatpong’s own ambivalence toward both the regulatory functions of western science and the relative flux of animist spirituality. He has criticized the distortion of Buddhist doctrine by Thailand’s military dictatorship, which has long weaponized the sanctity of religious tradition to justify oppression. “Animism has resulted in manipulation, sexism, and violence,” he reflects in a handwritten note included in the Memoria book.

People have a right to evolve, to be challenged intellectually…. [In] certain circumstances, the belief in ghosts hinders this process for the sake of preservation of culture. The rituals and belief need to be documented, but not protected when it chains people to their bubble in the time when we share space and resource[s], in [a] capitalist system.

But he has also confessed that animist intuitions saturate his own worldview, even now: “This idea that everything has life in it somehow…even though I don’t believe it, I cannot shake this feeling.”

Advertisement

*

Memoria’s second half takes place in a lush, creekside stretch of Pijao, cradled in mountains roiled by decades of guerrilla warfare. Here, Jessica encounters a man scaling fish amid the verdure, whose name also happens to be Hernán (Elkin Díaz). This older Hernán, like the titular character in Uncle Boonmee, has perfect recall, engulfed by ceaseless torrents of memory. But Hernán’s is a more roving kind of hypermnesia, able to replay memories housed in the trees and stones around him. He limits what he sees and where he goes, he tells Jessica, because “there are plenty of stories already.” “Like this stone,” he offers, picking up a chance object and relaying, as if by transmission, the story of a man whose friends robbed and beat him up during his lunch break. It happened before their time, but the sonic vibrations, he explains, “were embedded in this stone.” The first Hernán sought to grasp Jessica’s cryptic sound by remastering it in the studio’s hermetic hold; this one is at the mercy of his environment and the sonic deluge it circulates through him.

Soon, the pair have made their way to Hernán’s modest home, nestled in a swaying, sunlit copse. After they share a potent drink, Jessica peruses his room and sits on his bed, pausing, struck by a sudden recollection: “I was hiding under the bed with others…we could hear everything,” she recounts aloud. “They were searching for us.” She recalls her mother touching her fingers, her nose burning, skin peeling, but Hernán interrupts—she was never here. Like “an antenna” to his “hard disk,” he tells her, she is reading his memory. When Jessica begins to cry, moved by the sensations of trauma, he asks, in a line that seems both pointed and innocuous: “Why are you crying? They are not your memories.”

The question may not be strictly accusatory, but it returns us to the proprietary tensions Memoria raises throughout—about bones, flowers, stories wrested from the earth, and even the film’s own making. This is Apichatpong’s first production abroad, and he has said that he chose its setting for its relative unfamiliarity to both himself and Swinton, whose wan and angular face brandishes her alien presence from the film’s first scene. How might his interest in porosity play out in a region famously destabilized by endless extraction, whose terrestrial riches—petroleum, coffee, orchids—have been fodder for centuries of colonial plunder? Never mind the construction of La Línea; for decades, mining companies have exploded mountains for Colombian gold.

But Apichatpong knows that a protagonist disoriented by the lure of a novel locale is a trope in itself: Jessica’s namesake is the plantation owner’s wife in Jacques Tourneur’s I Walked With a Zombie (1943), another white woman whose itinerant fugue takes her through lands riven by colonial violence. He evades the exoticism that trope risks by locating mystery not in a region’s inscrutable terrain but in a lone, vexing sound, the through line in a film full of dissonance. Maybe Memoria is an attempt to ask what kind of narrative filmmaking is still possible when jungles, mountains, and the people in their midst are already brimming with so many stories of their own. Toward the end of the film, we learn, at last, the unlikely source of Jessica’s bang: an extraterrestrial vessel hidden in the forest’s canopy. The revelation feels a little odd, even twee, but it also makes sense from a director who has been testing, from his earliest features, just how many dimensions and ways into knowing a film can hold.