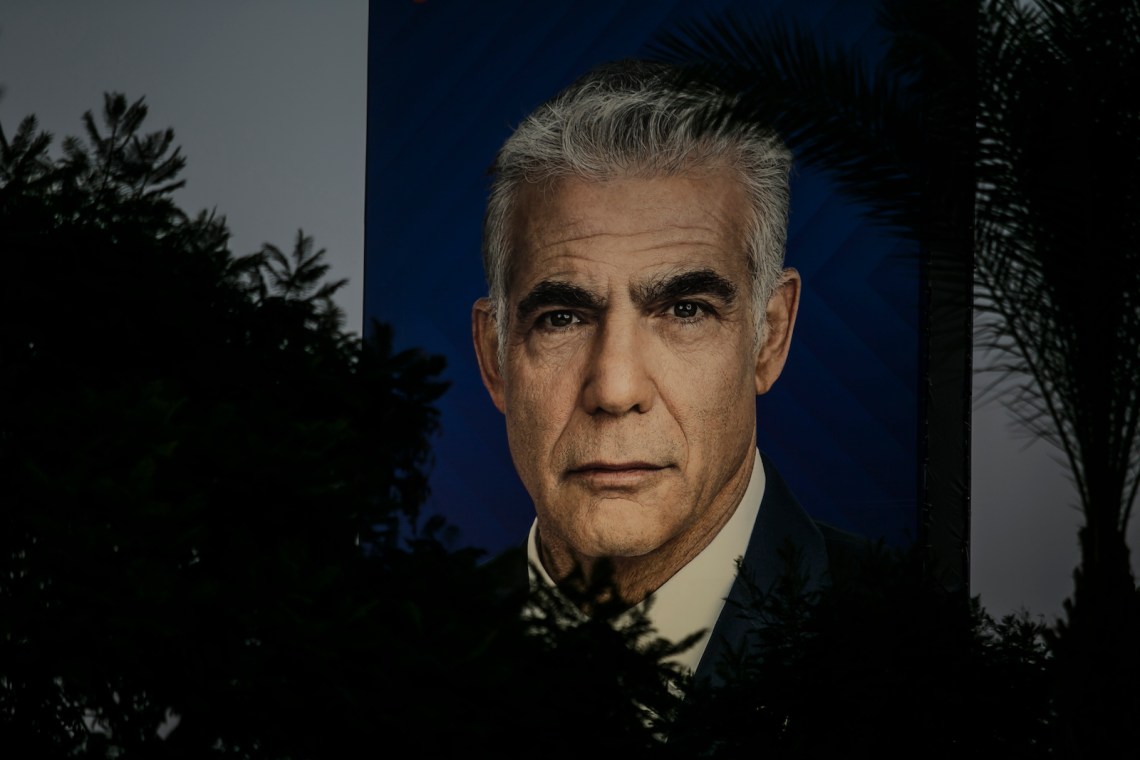

Now that Benjamin Netanyahu is poised to return to the prime minister’s residence, the miscalculations of the fractious bloc that momentarily displaced him appear in stark relief. Over the course of five elections since April 2019, the basic strategic assumptions of the disparate parties united solely by their opposition to Netanyahu hardened into a kind of common sense: that the centrist former TV host Yair Lapid was the most plausible alternative to Netanyahu; that there existed a significant segment of secular right-wingers and moderate religious Zionists who, disillusioned less by Netanyahu’s politics than by his personal conduct, would join the centrist and center-left parties in unseating him; and that it would be possible to unseat him without an explicit commitment to formal political cooperation with the parties representing Palestinian citizens of Israel.

This approach has failed. The parties opposed to Netanyahu’s right-wing religious bloc will need a new strategy if they ever hope to attain power, but there are many obstacles on the path to reinvention. A secular, social-democratic ethos was once hegemonic in Israel, but today secular liberals increasingly find themselves a minority among Israeli Jews. At the same time, the Israeli right has steadily radicalized, fueled by the daily exercise of violence and brutality required to maintain the indefinite occupation of the West Bank and the siege of the Gaza Strip. In this crucible, what remains of Israel’s left will either reinvent itself or vanish.

*

Yair Lapid was always a less than perfect candidate. His advantages over other would-be challengers to Netanyahu were mainly cosmetic—a familiar, handsome face and a TV career that had accustomed him to a life in the limelight. He was an avatar of secular Israeliness, famous for his columns in the daily Yedioth Aharonot and for breathily asking during interviews, “What’s Israeli in your eyes?”

He entered the Knesset in 2013 with a party boasting nineteen seats, propelled by the energies of the 2011 social protests, which had begun with frustration over the high cost of living but quickly devolved into an antipolitical bourgeois revolt. With a mandate to represent Israel’s urban middle class, Lapid served as finance minister in Netanyahu’s government until December 2014, when he departed for the opposition. His signature policy changes were ending the military draft exception for ultra-Orthodox yeshiva students—which infuriated the Haredi parties—and eliminating the value-added tax on first-time homebuyers.

Despite a decade in parliamentary politics, Lapid never articulated a coherent ideological alternative to the nationalist-neoliberal synthesis first formulated by Netanyahu: management of the occupation of the West Bank and siege of Gaza combined with tech-driven economic growth and increased consumer spending, which was spurred by lower taxes and liberalized import tariffs. His relegation to the opposition late in 2014, when Netanyahu dismissed him along with then justice minister Tzipi Livni, triggering snap elections, was a matter more of realpolitik and personal animus than of principle. Netanyahu had chosen to form a coalition with the Haredi parties, who would not, and would never subsequently, agree to sit with the arch-secularist Lapid.

Whereas for some politicians stock phrases and inspirational cliches dress up an agenda, for Lapid they took the place of one. As the comedian Lior Schleien, roughly Israel’s equivalent to Jon Stewart, caustically observed in late October, Lapid has staked out contradictory positions on nearly every issue, from the status of Jerusalem in any future peace negotiations—Lapid in the past claimed that “all of it is ours,” while more recently he endorsed a two-state solution—to his own service record in the army. In what has perhaps been his most sophisticated political statement, a manifesto published by the liberal daily Haaretz in March 2020, he drew on a Burkean notion of tribalism to defend privileging Jews over the idea of universal, egalitarian citizenship, and on a Hayekian concept of individual freedom. It was a conservative centrism in a defensive crouch, focused on preserving the status quo in the face of the threats Netanyahu’s return poses to the rule of law. It was also an explicit gesture toward the politics that Netanyahu and Likud, Israel’s “national liberal” party, once represented.

Whether this messaging reflected Lapid’s personal philosophy or not, it had a clear intended audience. For the last five elections, Israeli media and politicians have fixated on a political demographic referred to as the “soft right”—secular conservatives and territorial maximalists disillusioned by Likud’s turn to a religiously inflected right-wing populism, and “moderate” settlers and religious nationalists disturbed by the Kahanist takeover of religious Zionist politics. Their geographic centers were thought to be the affluent, tree-lined suburbs of Ra’anana (where former settler leader Naftali Bennett lives) and the so-called “consensus settlements” of the Gush Etzion bloc. It was imagined that enough of these voters could be swayed to vote against Netanyahu.

Advertisement

It is not that such people do not exist. In the winter of 2020 Gideon Sa’ar, an ambitious erstwhile Likud hawk who had once challenged Netanyahu for the party’s leadership, split to form New Hope, a party of his own directed at these voters. New Hope won six seats, and its members served in the fragile government headed jointly by Bennett and Lapid—until, ahead of the last election, it merged with former IDF chief of staff Benny Gantz’s Blue and White, with which it soon formed the right-wing, statist National Unity Party. But the soft right was much smaller than Lapid’s would-be coalition partners recognized. Like Never Trump Republicans, its adherents were overrepresented in the media and in elite policymaking circles. Among ordinary voters, they were scarce even compared to the Kahanist fringe that, by November 1, had ballooned into the Knesset’s third-largest party.

The persistence of the belief in this demographic was also a kind of political wish-fulfillment, born of the desire to return to a time before the radicalization of the religious Zionist movement. For there had, in fact, once been prominent moderates among the settlers: figures such as the late Rabbi Yehuda Amital, a founder of the religious Zionist flagship Yeshivat Har Etzion who supported the Oslo Accords, and his colleague the late Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein, who rebuked more right-wing religious Zionist rabbis for justifying the 1995 assassination of prime minister Yitzhak Rabin by a religious nationalist and exhorting religious soldiers to disobey orders to evacuate Jewish settlements during the 2005 “disengagement” from the Gaza Strip.

Yet they were, nonetheless, settlers living on occupied Palestinian land. “Both Rav Amital and Rav Lichtenstein chose to build their yeshiva beyond the Green Line,” Mikhael Manekin, a veteran activist and left-wing religious Zionist, observed on social media after the election. “In the end, the conditions of life influence ideology. Extremism doesn’t come from nowhere, but from the clear decision to bind religious life with the subjugation of another people.” On November 1 the Religious Zionist ticket led by Betzalel Smotrich and Itamar Ben-Gvir claimed the plurality of votes in supposedly establishment settlements like Efrat and Ofrah, as well as in hardline bastions such as Itamar and Yitzhar.

Perhaps the greatest error by Lapid, Gantz, and other leaders of the anti-Netanyahu camp was their refusal to accept a simple mathematical fact. Any path to blocking Netanyahu’s return required open cooperation not only with the moderate Islamist party Ra’am—which became the first independent Arab-led party to enter a ruling coalition when it joined the Bennett-Lapid government in 2021—but with the other Arab-led parties as well. After the March 2020 elections, Gantz received more endorsements than Netanyahu for prime minister, giving him the first stab at forming a coalition. Ayman Odeh—then the leader of the Joint List, a coalition of Arab-led parties that began to collapse in the winter of 2021—had committed to supporting the formation of a Gantz-led minority government while remaining outside the coalition, as the Arab-led parties Hadash and Mada had done for Yitzhak Rabin’s minority government in 1993. But members of Gantz’s party rejected a minority government backed by the Joint List. Gantz joined another Netanyahu-led government instead.

Such hostility to a coalition supported by the Arab-led parties never disappeared. Throughout the campaign, Lapid could never articulate a full-throated commitment to Jewish-Arab political partnership out of fear that doing so might give ammunition to the right. Yet this reluctance was not just a matter of strategy. “There were ideas that we couldn’t agree with, and [so] they couldn’t be in a government,” Yesh Atid MK Karine Elharrar said of the Arab-led parties in a post-election interview with Israel’s Army Radio earlier this month. Elharrar is far from alone in this view. Those ideas—the demand for full civil and political equality for Palestinian citizens of Israel and an end to the occupation of the West Bank and the siege of the Gaza Strip—proved unacceptable for much of the anti-Netanyahu coalition.

In the summer ahead of the November elections, pollsters had stressed repeatedly to Lapid that his equivocation could depress Arab voter turnout. When I interviewed him for my previous piece for the Review in August, Ron Gerlitz, executive director of the political psychology research group aChord, told me that Lapid risked losing “seats for his bloc.” His prediction appears to have been borne out. While this month’s 53.2 percent turnout among Arab voters was higher than the 44.6 percent of the March 2021 election, it was much lower than the high watermark of 64.8 percent in March 2020, which saw the then-united Joint List emerge as the third-largest faction in the Knesset. This time, two Arab-led parties, Ra’am and Hadash-Ta’al—a merger of Odeh’s Hadash and the liberal nationalist party Ta’al, headed by Ahmed Tibi—finished with ten seats total, just shy of the twelve seats that, according to the pollster Samar Sweid, would have prevented Netanyahu from forming a coalition. Balad, the Arab-nationalist party that split from the Joint List this fall, failed to cross the electoral threshold.

Advertisement

But even if the anti-Netanyahu bloc combined with the Arab-led parties had won more seats than Netanyahu’s right-wing and Orthodox bloc, that would have only meant yet another round of elections as long as Lapid and Gantz’s parties objected to a minority government supported by Hadash-Ta’al. Given the choice between accepting political equality with Palestinian citizens and letting Netanyahu return to power, they repeatedly chose the latter.

*

The persistent inability of the liberal, secularist, and social-democratic parties to form a governing coalition is the culmination of a profound yet gradual shift in Israeli society. Over coffee in a Jerusalem café this summer, a young Israeli academic floated the theory that the seventy-five years since Israel’s founding can be divided roughly into three periods, each oriented by a different central question. From 1948 to 1977, the question was what kind of state was to be built. Menachem Begin’s election in 1977, followed by his unlikely peace treaty with Egypt’s Anwar Sadat, marked the transition to the next phase, which lasted from 1978 to 2005. The question then was what peace might look like. In the aftermath of Rabin’s assassination, the collapse of the 2000 Camp David talks, and the outbreak of the second intifada, the horizon of a two-state solution receded. The Israeli public turned inward and began to ask a new question: What is the meaning of a Jewish state?

The last decade-plus of Netanyahu’s rule has seen that question gradually answered in favor of traditionalist Orthodoxy and religious nationalism. In the 2010s, the term “religionization” began to appear in work by scholars of contemporary Israeli affairs. It was both an approximate translation of the Hebrew neologism hadata—which refers to the increasing prevalence of religious language, themes, and symbology in Israeli public life—and a diagnosis of the broader shifts that Israeli society appeared to be undergoing. As the scholar Yoram Peri put it, “it appears that the collapse of [Labor] Zionist hegemony in Israel is being filled by an Orthodox Jewish approach.”

Hadata had become a keyword in a new culture war. Parents of students enrolled in secular state-run schools complained that Orthodox and right-wing religious groups were overseeing a range of activities within them, in some cases rewriting curricula, as part of a multimillion-shekel initiative funded by the ministry of education—headed at the time by Bennett—to “deepen Jewish identity.” The Secular Forum, an NGO founded in 2011, warned that Israel’s public education system was “undergoing an aggressive religious radicalization to the detriment of our democratic society.” Even where religious programming was not explicitly nationalist, it raised secular parents’ hackles.

But the issue of school activities and curricula was a symptom, not a cause. While religion in Israel has always been a more public matter than in Western liberal democracies, Israel’s lightning victory in the 1967 war unleashed a messianic fervor that gradually remade the relationship between synagogue and state. The hitherto dominant Labor Zionist ethos—which imagined the Zionist revolution as in part the liberation of the Jews from the strictures of traditional religion—began to fall away. A new religious nationalism, strongly infused by a right-wing Jewish millenarianism, took its place. By the 1980s the surging settler movement imagined replacing the secular state with a halakhic kingdom and expelling the Palestinians from the West Bank by force.

The spread of the new religious Zionist hegemony accelerated rapidly through the 2000s, as the settler right assumed leadership roles in the army, the media, and the schools. By the time hadata had become a matter of public debate beyond the academy, the quiet revolution in Jewish Israeli life was mostly complete; the secular parents’ protests were much too little, too late. Not only were religious Zionists firmly ensconced at all echelons in the leadership of the state—serving as IDF division commanders and ministers of education—but even the once politically quietist Haredim, ultra-Orthodox Jews, had joined in efforts to reinforce traditionalist Judaism as the foundation of Israeli identity, objecting to attempts to curtail the power of the rabbinate or recognize conversions and marriages performed by non-Orthodox rabbis.

This shift has reverberated far beyond politics. A nationalist form of traditional religion increasingly suffuses the Israeli public sphere. Sometimes the results have been amusing: male celebrities wearing phylacteries posted smoldering selfies; pop singers who’d never been devout began to pepper their lyrics with “B’ezrat hashem.” Liberal educational advocates tried to give the turn to religion a pluralist spin and launched initiatives of their own to teach non-Orthodox approaches to the Torah and Talmud in public schools, but they only supplemented the growing saturation of Israeli public life with religious texts and themes.

Religionization was in some sense a vanguard project of religious Zionists. But the rhetoric in which they cast their bid for leadership of the state—the putative defense of Jewish identity in Israel—also became the ideological glue of a broader, emergent bloc comprised of Mizrahi traditionalists, Sephardic and Ashkenazi Haredim, and the nominally secular ethnonationalists of Likud. Begin had pioneered this appeal to Jewish tradition in the late 1970s by making Likud the party of the Mizrahi working classes excluded by the ruling Labor Zionists. Netanyahu perfected it.

Since his first bid for prime minister in the 1990s, Netanyahu, despite being neither religious nor Sephardic, demonstrated an almost preternatural ability to unite and galvanize these groups against those they took to be their enemies. In 1996 the Chabad Hasidic sect campaigned for him with the slogan “Bibi is good for the Jews,” implying that anyone who voted against him was hostile to Jewish interests. In 1997 Netanyahu was recorded whispering to Rabbi Yitzhak Kaduri, a Sephardic kabbalist, that “on the left, they’ve forgotten what it means to be Jewish.” Israeli political discourse came to revolve around the division between “the people”—good Israeli Jews—and “the left,” traitors more loyal to “the Arabs” than to their own people. To oppose prayer in military ceremonies or religious instruction in public schools came to be seen as a betrayal of Jewish identity; to support territorial compromise, a betrayal of Jewish security.

Israel’s putative liberals did not help their own case. There is a long history of secularist and Labor Zionist condescension and disgust toward traditionalist religion—often with a European-colonialist and racialist cast, aimed at Mizrahim and Haredim. That history has continued into the present. During a speech at a 2015 election rally for the center-left parties held in Tel Aviv’s Rabin Square, the artist Yair Garbuz lamented that the country had been “taken over” by “amulet-kissers, idol-worshipers, and those who prostrate themselves on the graves of sages.” The right quickly seized on Garbuz’s remarks as proof of the left’s hatred of Judaism.

With the near disappearance of the two-state solution from political discourse, left-wing and centrist parties such as Meretz and Lapid’s Yesh Atid made secularist policies like public transportation on the sabbath a significant part of their platforms. Yet they failed to realize that, when a 2009 survey found that more than 60 percent of Israeli Jews “believe that the State of Israel should ensure that public life is conducted according to Jewish religious tradition,” this agenda was an electoral non-starter. Finding the new Israel alternately repulsive and unrecognizable, Israel’s WASPs—white, Ashkenazi, secular progressives—sunk into a kind of cultural despair.

But while they understood that they had been defeated politically, their sense of victimhood blinded them to the power they continued to wield. Israel’s secular, Ashkenazi elites have, after all, been the greatest beneficiaries of the country’s high-tech, capitalist globalization: far more likely to be university educated, they dominate the upper ranks of corporations, law firms, and academia. The secular elite’s refusal to acknowledge its own enduring privilege further enabled Netanyahu and the right to use the “Jews versus the left” division as a weapon of right-wing class war. Paradoxically, while it was Netanyahu’s own economic policies that enriched the largely secular elite, he has also been able to harness the resulting resentment of the Mizrahi working class and religious traditionalists to keep the right in power.

The defense of Judaism, Jewish identity, and traditionalist religion is crucial to this strategy. To paraphrase Stuart Hall’s famous quip that race is “the modality through which class is ‘lived,’” one might say that in Israel orientation toward religion is the modality through which class is lived. This is true in a double sense: not only is a religious definition of Jewish nationhood wielded to affirm Jewish superiority over non-Jews, it also defines the internal divisions within Israeli Jewish society. To attack religious observance or religious folk practices is understood as an assertion of an Ashkenazi, secular, enlightened supremacy over working-class Mizrahi traditionalists and the Orthodox that dates to the founding of the state. The defense of religion in the public sphere and the demand to nationalize Judaism and Jewish identity are expressions not simply of a right-wing theopolitics—although they are that, too—but of a subaltern challenge to the country’s cultural elites.

*

Today Israel’s progressive forces are at their nadir. Hadash and Ta’al claim only five seats combined; the much-diminished Labor, four. The civil-libertarian, social-democratic Meretz has no seats for the first time in thirty years. Supporters of territorial compromise and a reinvigorated welfare state face not merely four long years in opposition but the possibility of terminal obsolescence. For the remaining fragments of the Zionist left—Labor and whatever becomes of Meretz—survival will require at least one of two fundamental, and therefore unlikely, shifts in orientation.

One is in the realm of synagogue and state. As long as Jewish Israeli progressives maintain their instinctual hostility to religion in the public sphere and antipathy toward the Orthodox, they will remain locked out of political power. While the leaders of the Haredi parties have steered their ships in formation with Netanyahu, they are not strongly committed hawks, and in the past they have supported territorial compromise; under the right conditions, they might do so again. As the Haredi journalist Yisrael Cohen wrote in Haaretz, “the humanists and pacifists” of the left must ask themselves “if it’s really so important that yeshiva students serve in the IDF”—so important that it takes priority over fighting the extreme right.

The second shift concerns the relationship between the Zionist left and the Arab-led parties. To continue existing as a political force, however marginal, the Zionist left will need to accept Palestinian citizens of Israel unconditionally as equal political partners, which means ceasing to demand that they become Zionists before they can be acceptable allies. And yet after this month’s elections, leading Israeli liberals have taken the opposite approach. In Haaretz the veteran commentator Uri Misgav accused Odeh, Tibi, and two Hadash MKs—Ofer Casif and Aida Touma Suleiman—of costing the anti-Netanyahu bloc the election because they criticized the Bennett-Lapid government and defended the right of Palestinian armed resistance in the West Bank. On Twitter, the satirist Einav Galili—Lior Schleien’s erstwhile colleague on the popular “State of the Nation” show—responded defensively to calls for deepened Arab-Jewish partnership. “I believe in full equality,” she wrote, “and racism is an abomination in my eyes, but when Touma-Sulieman enthusiastically praises those who want to kill me and my children, I’ll refuse—with your permission or not—that she represent me in the Knesset.” Misgav and Galili’s comments reflect the hypocrisy at the heart of the Zionist left: in theory it calls for equality, but in practice it requires that Palestinian citizens of Israel surrender their demands for full freedom.

The next four years all but guarantee a dramatic reconfiguration of Israel’s judiciary to shore up Jewish ethnocracy, a crackdown on human rights activists, increased brutality against Palestinians on both sides of the Green Line, and additional steps toward annexing the West Bank. The coalitional math is such that without either a dramatic rapprochement with the Haredi parties or an embrace of full Arab political participation, there is little hope of ever challenging the ascendant far right. These changes demand whoever remains on the center-left leave their secular Zionist priors behind. They can maintain a melancholic attachment to the supposed glory of their past, or they can have a fighting chance in the future. They cannot have both.