In a cramped, fluorescent-lit office in Tripoli up several flights of stairs, a middle-aged official and his staff labor on what is perhaps the most important work for future generations of Libyans. It’s a command center of sorts: flashing computer monitors on desks, cables everywhere, and satellite maps on the wall marked with great swirls and arrows. The battle isn’t against a military opponent, like the innumerable armed groups and their political backers who have been fighting for power and economic spoils in this oil-rich state since the ouster of Muammar Qadhafi during the NATO-backed revolution of 2011. The scourge is far more insidious, and the country’s bickering elites seem woefully unprepared to tackle it.

This is the temporary headquarters of Libya’s National Meteorological Center, a nondescript poured-concrete building tucked away on Qurji Road, named for an Ottoman naval captain who also commissioned an ornate mosque in the nearby Old City. The affable, wiry director of the center, Ali Salem Eddenjal, greets me with an apology for the tight spaces: he’s had to relocate from another part of the capital because of violent militia clashes, a story of forced displacement that many Libyans know all too well.

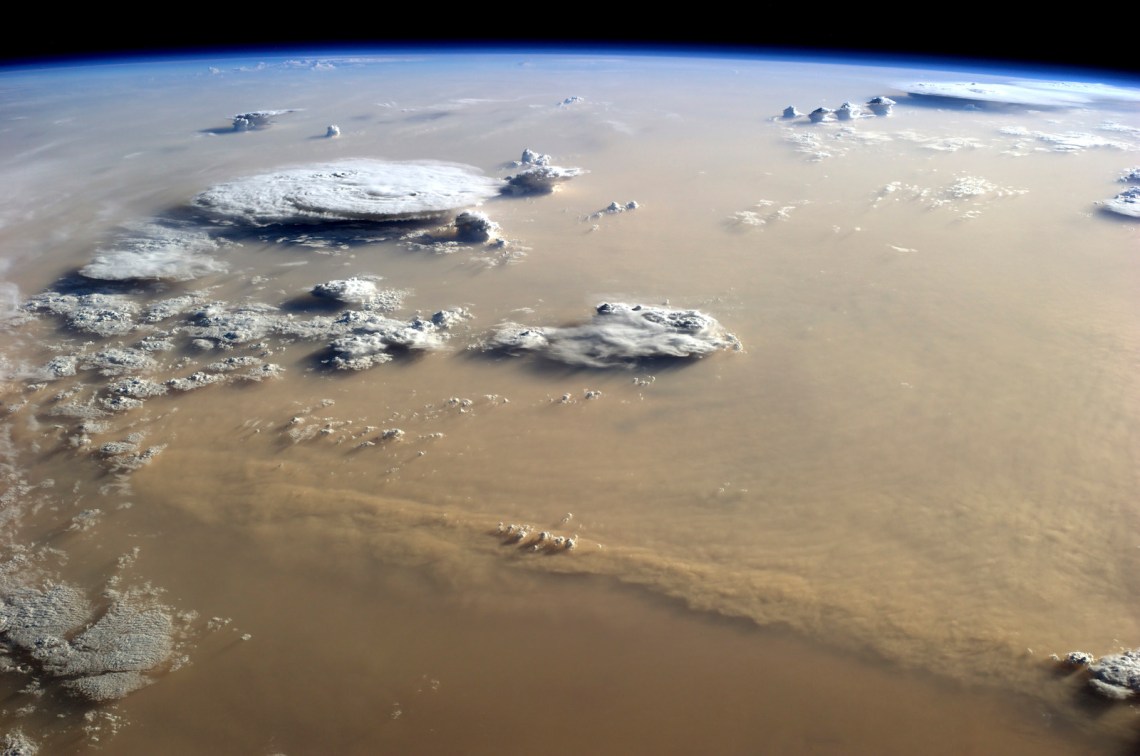

Still, Eddenjal and his team press on, diligently monitoring, analyzing, forecasting, and reporting a stream of alarming data that most Libyans already experience firsthand. The country is getting hotter, its droughts more severe and prolonged, its rainfall scarcer, its sand and dust storms more powerful and frequent. The latter phenomenon was on spectacular display in March and April, when a blizzard of particulates barreled up from the Sahara and blanketed Tripoli and the surrounding region. The salmon-colored haze, stunning on Instagram, prompted the suspension of flights from the city’s airport. It also elicited a warning from the European Union Mission to Libya that the country’s authorities needed to address the current and impending effects of climate change.

It’s an admonition that Eddenjal, who wrote a graduate thesis on climate change, doesn’t need to hear. For years he’s been forecasting the devastating effects of anthropogenic global warming on his water-stressed country of nearly seven million people—effects that will be exacerbated by years of conflict, corruption, infrastructural decay, and environmental deterioration. The startling picture he paints in many ways augurs the future of much of North Africa and the Middle East. Libya’s mean annual temperature, along with that of the entire southern Mediterranean, is climbing faster than the rest of the world’s, and is expected to increase two degrees Celsius by 2050. Yearly rainfall is decreasing at a similarly rapid clip, while sea levels along Libya’s long coast are rising by as much as three millimeters per year.

In a desert country where the vast majority of the population resides in a narrow sliver of territory near the sea, these changes will be catastrophic. As heat, drought, and food insecurity take their toll on Libya’s interior, the already feeble service and sanitation infrastructure in northern cities and towns will buckle under an influx of Libyans from the hinterland, who join the thousands of citizens still displaced by war. Potable water, eighty percent of which is tapped from fossil aquifers deep in the desert by a system of pipelines called the Great Man-Made River, will be diminished by the evaporation of open reservoirs and unsustainable extraction. With soaring temperatures also comes more demand for electricity, which will push an overburdened grid to the point of failure, with life-threatening consequences for health and food security. Meanwhile, storms will surge over shoddy drainage systems, and some coastal areas, like the eastern port city of Benghazi, will be severely damaged or inundated.

Added to this crisis are two glaring precarities. Libya’s dependence on oil exports to finance its bloated budget for the public sector—which employs 85 percent of the population—has left it dangerously exposed to the impending decline in global oil prices, known as “peak oil,” resulting from the transition to renewable energy and net-zero carbon pledges. And Libya’s miniscule, rapidly failing agricultural sector and reliance on imports for more than three quarters of its foodstuffs render it similarly defenseless against food supply shocks. It’s easy to imagine the cataclysm on the not-too-distant horizon: staggering losses of life and economic ruin, accompanied by the violent dissolution of the country into a patchwork of domains ruled by predatory militias using precious water, electricity, fuel, and food as sources of authority.

Portents of this dystopia have already arrived. Recall, for example, the spectacle a few years ago of Tripoli residents digging for water through concrete outside their homes, after the sabotage of the Great Man-Made River—a favored target of criminals and militias in the south. Or the contest in and around the capital among neighborhoods, backed by armed groups, over electricity rationing during hot summer months. Or the all-too-frequent blockades of oil ports and fields by armed groups and political factions, contributing to long queues for gas and electricity during outages and creating a market for private fossil-fuel generators that spew exhaust in close proximity to people’s homes.

Advertisement

But the most tragic harbingers of the darkening climate future are Libya’s thousands of refugees and migrants, many from African states to the south, who’ve fled food shortages, violence, and crushing poverty—hardships exacerbated by environmental degradation and climate events—only to suffer horrific abuses at the hands of traffickers and Libyan armed groups, sometimes backed by the Libyan state and, indirectly, an increasingly nativist Europe.

Eddenjal knows all of this and more. But for now, he wants to tell me about sandstorms.

*

Sand and dust storms have become a striking visual avatar for the climate crisis in Libya, though anthropogenic climate change is not their cause. They are natural phenomena that have been around for millennia; Saharan dust plumes carry minerals like iron and phosphorous thousands of miles, ultimately fertilizing the Amazonian rainforest and nourishing phytoplankton in the Atlantic and Mediterranean, thereby reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. But their effects on human livelihood and health are decidedly not beneficial. Their smaller particles wreak havoc on the body, causing or worsening respiratory illnesses and damaging tissues and organs, especially the heart. In the Middle East alone they inflict 150 billion dollars’ worth of economic loss annually. It was a sandstorm that contributed to the lodging of a container ship in the Suez Canal last year, holding up global supply chains for six days.

The territory of Libya has long been both a source and destination of sandstorms, but in the last few years Eddenjal and his team have been recording worrying changes “in [their] seasonality, frequency, duration, and intensity.” The plumes have started coming earlier, in the spring, not only from the dry flats and deserts of Libya’s south but from semi-arid and cultivable areas along the coast, which extended droughts have stripped of vegetation and left more susceptible to wind erosion. Then, locally, there is what Eddenjal calls the “abuse” of the land: human-caused degradation of soil through mismanagement, urbanization, intensive farming, and overgrazing. Even military conflict is said to contribute, by wracking the ground with tracked vehicles, trenching, and shelling (though at least one study has concluded that its effects on sandstorms in the Middle East may be overstated).

In Libya, these processes have been starkly visible for at least a decade. Money-hungry elites and militias have grabbed vast tracts of farmland and rangeland, parceled them out, and converted them into shops, apartments, and garages. The forests that ring the capital—which were planted during the last century to foster a beneficial microclimate, aid farming, and prevent desertification—have been chopped down in a similar lust for profit. Some Libyans hold NATO and the revolution responsible for this ravaging, but in truth deforestation started in the 1980s with the Qadhafi’s quixotic collectivization of property, which involved dismantling Libya’s ministry of agriculture and the disbanding the police force charged with guarding the forests. The spoliation has only been worsened by periodic clashes around Tripoli since the dictator’s fall, especially the 2019–2020 war for the capital between militias loyal to the government and those commanded by an eastern-based warlord named Khalifa Haftar, who was militarily backed, ironically, by the two Arab states (and US allies)—Egypt and the United Arab Emirates—hosting recent and forthcoming UN climate summits. I saw firsthand the results of their interventions: shell-pocked vineyards and fields, blasted orchards, and ruined farmhouses.

All of this is personal for Eddenjal, as I can tell from the bright tricolored flag draped on the wall of his office. It’s the adopted banner of the Amazigh people, members of a diverse ethno-linguistic group that stretches across North Africa who have long struggled against socioeconomic, political, and cultural marginalization. In Libya they are also among the most susceptible to climatic effects on agriculture, especially in the Nafusa Mountains to the west of Tripoli. There, olive farmers have seen their harvests ruined by years of declining rainfall and shifts in the seasonality of droughts and sandstorms—adding to the disruptions of conflict and electrical outages, which have raised the costs of agricultural production. A mayor from that region told me that some villages are emptying out and moving to the capital.

Elsewhere on the fringes of Tripoli it’s a similar story. In an area called Sidi Sayeh, the site of a massive landfill and intense fighting, a septuagenarian farmer named Bashir Alafrak told me that “the water is gone.” He said his harvests of sugar beets, potatoes, and watermelons had fallen by as much as sixty percent. Not only is rainfall declining; he now has to dig deeper and deeper for groundwater, which requires prohibitively expensive equipment. A professed supporter of the Qadhafi regime, he acknowledges its environmental mistakes but directs most of his wrath for his predicament against the “nepotism” of the country’s “revolutionary men,” meaning the militias and their political backers. Now he fears he will lose his farm, creating perilous hardships for his family of five, which he supports entirely from his crops—a crushing blow to his identity. “I am a farmer,” he says defiantly, “and will remain a farmer for all my life.”

Advertisement

Despite Libya’s vulnerability to climate change, the country emits more carbon per capita than any other in Africa and even surpasses some leading industrial nations. “The Libyans are in a whole different league,” a western climate advisor who’s worked extensively on Libya told me. This outsized footprint, he says, is partly due to the flaring or venting of excess gas as a byproduct of inefficient oil production. While Libyan oil authorities have taken some modest steps to curtail this practice, they could do much more—as could the country’s main downstream consumer, the European Union. More broadly, Libya’s fractured leadership has not begun to address climate change mitigation in a systematic, meaningful way. Of the 193 signatories to the Paris Accords, Libya is the only one that has not yet submitted a document called a Nationally Determined Contribution, an action plan to reduce emissions and protect society from climate impacts.

This paralysis seems in no small measure due to the fragmentation of Libya’s climate response and factional jockeying over who owns climate policy. To his credit, the previous prime minister, Fayez al-Sarraj, created an interministerial climate committee in 2020 that was supposed to minimize such friction and coordinate steps to diversify the oil-based economy, incentivize a transition to renewable energy by reducing fuel and electrical subsidies, and rationalize water use. But given the deep divisions in the country, that body exists mostly on paper, leaving the bulk of climate oversight to the minister of environment.

More recently, the current prime minister, a tycoon-turned-populist named Abd al-Hamid al-Dabaiba from the powerful port city of Misrata, is trying to take control of climate policy by establishing a new climate authority in his office. The man responsible for that effort, also a Misratan, is someone I’ve known for years, though I was surprised to learn of his appointment when we met this May: he’s a capable civil society leader and lawyer, but not an environmental or climate specialist. He told me he’d authored a climate strategy document and placed it on his boss’s desk. It remains unsigned.

In the midst of this top-level gridlock and lethargy, a variety of grassroots environmental and civil society groups have stepped forward on climate resilience with admirable alacrity and creativity. The head of the decade-old Tree Lovers Association, for example, explained to me how its volunteers have engaged in reforestation and other greening activities in western Libya. And yet, as I’ve seen firsthand, such organizations in Libya have struggled against mounting threats from militia groups and the intelligence services—the two are often intertwined—who view any issue-based mobilization as a threat to their dominance. Many activists have consequently left the country. “Collectively, we paid a high price,” the tree association leader told me.

*

A fifteen-minute drive south from the National Meteorological Center takes you across the multilane artery of Airport Road and into a neighborhood called Abu Salim, an overdeveloped swathe of housing projects and tight streets. This too is a place that is acutely exposed to climate risks, though in ways that are not completely obvious.

In contrast to the centuries-old Tripoli downtown, Abu Salim is relatively new, planned and built by Qadhafi to accommodate arrivals to the capital from the country’s poorer tribes in the desert interior. It has a bloody history. In 1996 inmates in a notorious prison in the quarter, which housed political prisoners, rioted and were repressed by security forces in a two-day killing spree that left 1,200 dead. The unresolved legacy of that massacre was one of the sparks of the 2011 revolution, though the Abu Salim suburb itself, home to loyalists like members of the security forces and their families, was among the last places in the capital to fall to the rebels.

In the years of strife that followed the revolution, Tripoli’s neighborhoods came under the sway of powerful militias that ruled them as fiefdoms, exacting tribute and harassing residents while claiming to provide law and order.1 Abu Salim fell to an armed group that now belongs to the Stability Support Apparatus, an umbrella formation billing itself as a government law enforcement entity that receives government funding. In fact it is the private militia for Abd al-Ghani al-Kikli, who goes by his nom de guerre, Ghneiwa.

A short, balding man with a creased, sun-bronzed face, Ghneiwa met me one evening in June 2019. It was just two months after Haftar had launched his attack on Tripoli, and Ghneiwa’s fighters were among the thousands of young men from the city’s frequently quarreling militias that had put aside their differences and rushed to form a cordon defense in the suburbs. By then the front had stabilized and the militia leader seemed relaxed, disarmingly attired in an oversized polo shirt. We sat on folding chairs on a terrace at his headquarters, overlooking a football match on a field below and, further beyond, a warren of shops.

Ghneiwa’s rise to become the veritable don of Abu Salim followed the formula of other post-Qadhafi chieftains—a mix of personal charisma, political patronage, and violence. Amnesty International has alleged that the Stability Support Apparatus has carried out assassinations, torture, and kidnapping for ransom. Ghneiwa’s power has also hinged on his paternalistic management and selective dispersal of services to the neighborhood’s residents. Over the past several years, as summertime temperatures spiked in Tripoli, electricity—air-cooling, food-preserving, lifesaving—has been among the most precious and contested of those services.

Electricity generation in Libya is staggeringly wasteful and costly, generated by burning natural gas, fuel oil, and diesel, as well as crude oil. It is also heavily subsidized, leading to exorbitant consumption, which further stresses an infrastructure already corroded by years of instability—only thirteen of the country’s twenty-seven thermal power plants are operational—and causes outages of up to forty hours at a time, especially during the summer and winter when demand is high. That, in turn, has sparked fierce and widespread protests. To minimize blackouts and social unrest, the state-owned electrical company has for years implemented a system called “load shedding”—rationing periodic outages proportional to consumption—between different neighborhoods in the capital and nearby municipalities. But the militia bosses of these feuding locales quickly grew suspicious that they were shouldering an unfair burden compared to their rivals.

Unsurprisingly, competition erupted. Armed militias began reportedly disabling the connected breakers on the grid in 2018, making it impossible for the utility company to ration electricity and causing overtaxed turbines to explode. Still others pressured the control room administrators to reduce their share of the outages. This was a tactic Ghneiwa’s militia seemed to practice with particular adroitness, earning him plaudits among residents of Abu Salim and envy among the inhabitants of the downtown districts. As of late this summer, the municipality was still exempt from the utility’s new and unpopular austerity plan.

*

Kilowatts are not the only climate-affected currency of Ghneiwa’s power in Abu Salim. In recent years, he and his men have engaged in an enterprise of a far more abominable sort, one that global warming is projected to worsen. I got a glimpse of it back in the summer of 2016 at a walled compound built on a former scrap-metal yard not far from Ghneiwa’s headquarters. A sunny foyer, sprinklered lawns, and a mural of leaping dolphins belied the darkness within.

This was the Abu Salim Detention Center—not the prison of Qadhafi-era notoriety, but another facility reserved for holding irregular migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers, mostly from Africa. It is ostensibly managed by the Tripoli government’s Department of Combatting Illegal Migration, with indirect funding and backing from the EU and its member states. But in reality it is the purview of Ghneiwa’s armed group—an arrangement that exists at the two dozen other detention facilities in Libya, in which the militia controlling the territory where a center is located receives what amounts to official license to torture, extort, enslave, and murder the prisoners in its charge.

I’ve been to half a dozen of these sites over the years, recording the names and stories of those inside, even if what I saw and heard often eluded the descriptive power of words or photographs. Accounts of interminable truck-borne trips across the desert, watching fellow passengers slowly expire of heat or tumble off the vehicle to die in the sands; of forced labor, cleaning toilets at militia checkpoints; of mock executions and pledges of suicide. The months and years of malnutrition from subsistence on macaroni or rice. The gasoline-burned and scabies-ravaged bodies. The beatings. Their faces are as distinct as ever in my memory. The welder, the student, the semiprofessional midfielder. The nearly naked disabled man with the shaved head, squatting on the floor. The three Nigerian women, one of them pregnant, describing their sexual torment.

These were only the terrestrial afflictions they had suffered. “The land and the sea are not the same,” one migrant said to me, describing the harrowing Mediterranean passage to Italy that claims thousands of lives every year. I’d heard of the ordeals of survivors who’d seen their relatives slip beneath the waves, and met the unscrupulous smugglers who’d fixed these crossings with shoddy inflatable craft. And I’d gone on nighttime patrols with the Libyan coast guard—who sometimes colluded with traffickers themselves—as they sought to render the migrants back to Libya illegally, with support from EU member states in the form of training, funding, and the provision of equipment like boats.

At the Abu Salim center, the warden I encountered was candid with me. “I won’t deny that we beat them,” he said. He apologized for being late: he’d just returned from a funeral for a friend who’d been killed in crossfire between Ghneiwa’s group and another militia. Dressed in a long gown and leather sandals, he reminded me that he was a captain in the police, though in practice that meant little, as his ultimate loyalty lay with Ghneiwa. He had over two hundred migrants and refugees, separated by nationality, in his charge. “We never keep the ones from Eritrea and Ethiopia together,” he said, escorting me to a cavernous hall of cells with cage doors.

I entered one of them, filled with young men from West Africa, including roughly thirty from Gambia. Gambia, an impoverished riverine nation, is the smallest country on the African mainland, but at the time of my visit to Abu Salim ranked among the highest per capita in the numbers of irregular migrants who attempted the Mediterranean crossing. It’s not hard to see why: over three quarters of the population depends on subsistence farming and is thus severely vulnerable to food insecurity, especially as urbanization, deforestation, rising temperatures, floods, and droughts shrink cultivable land. None of the men before me expected to earn a living from farming and fishing anymore—but none had expected their path to end in the abuses they now endured. One of them lifted his shirt. “We don’t understand their language, so this is how they rectify us,” he said, pointing to two large welts on his shoulder, which he claimed were from beatings with a pipe.

The warden told me these men rarely, if ever, went outside the cell for fresh air, since he had too few guards to oversee them. By the time of my terrace meeting with his commander in the summer 2019, that staffing had been stretched even thinner, while the prison population had swelled. Faced with the strain of fighting Haftar, the militia boss decided that fall to free hundreds of detainees in Abu Salim onto the streets, leaving them short of food and water and exposed to artillery and airstrikes, which had already killed dozens of migrants. Others he forcibly conscripted into the war effort to service weapons and transport ammunition.

At the end of that war in 2020 Ghneiwa emerged as an even more formidable figure, with an expanded official mandate to block migration, brutally, with alleged financial support from the EU. Despite widespread calls for reform, the latest government in Tripoli shows little appetite for loosening the grip of the armed groups: its newly appointed director of the department for countering migration is a militia leader who previously oversaw one of the capital’s most heinous detention sites.

Distinguishing climate-related distress from the myriad other factors that compel migrants—including, increasingly, from Egypt, as well as Syria and South Asia—to traverse Libya’s ecosystems of abuse is difficult, but the fallout from global warming is expected to increase in salience as a driver for human movement. A chorus of scholars, meanwhile, have warned against the use of the term “climate refugee” on the grounds that its politicization could lead to harmful policies like containment and refoulement.2 They argue that the wealthier states of the Global North should work to promote both in- and out-migration as constructive modes of climate adaptation and accordingly fund programs that make it a safer enterprise. But policy deliberations lag far behind in addressing this challenge, and in Libya there are precious few signs of those changes happening. Absent more institutionalized reforms, Libya’s territory and its profiteering militias will likely continue to serve as a convenient out-of-sight catchment for European governments—and especially right-wing, xenophobic politicians—to offload their climate responsibilities.

In the meantime thousands of aspirants for a better life languish in abhorrent conditions and wait. They scribble messages to the outside world on the concrete walls of their cells, like those I’ve seen in so many Libyan prisons: “We are Humans, Not Animals”; “Every Human Has a History.”