When I learned a few weeks ago that the composer and music critic Ned Rorem had died—a lifelong apostle of youth who dreaded turning fifty, he had somehow lived to be ninety-nine—I felt a complicated pang. I first came across Rorem’s diary in 1971, when I was a junior at the Putney School, in Vermont. Our Spanish teacher, Emilia Bruce, instructed us to keep diaries in Spanish as part of our regular assignments. She suggested we might take Anaïs Nin as a model. Imagine! I loved Nin’s diaries. They introduced me to Henry Miller and Paris and Otto Rank. But mostly what I found in them was a feeling for writing as immediate, fragmented, improvisatory—characteristics I still value in my own work and in that of others.

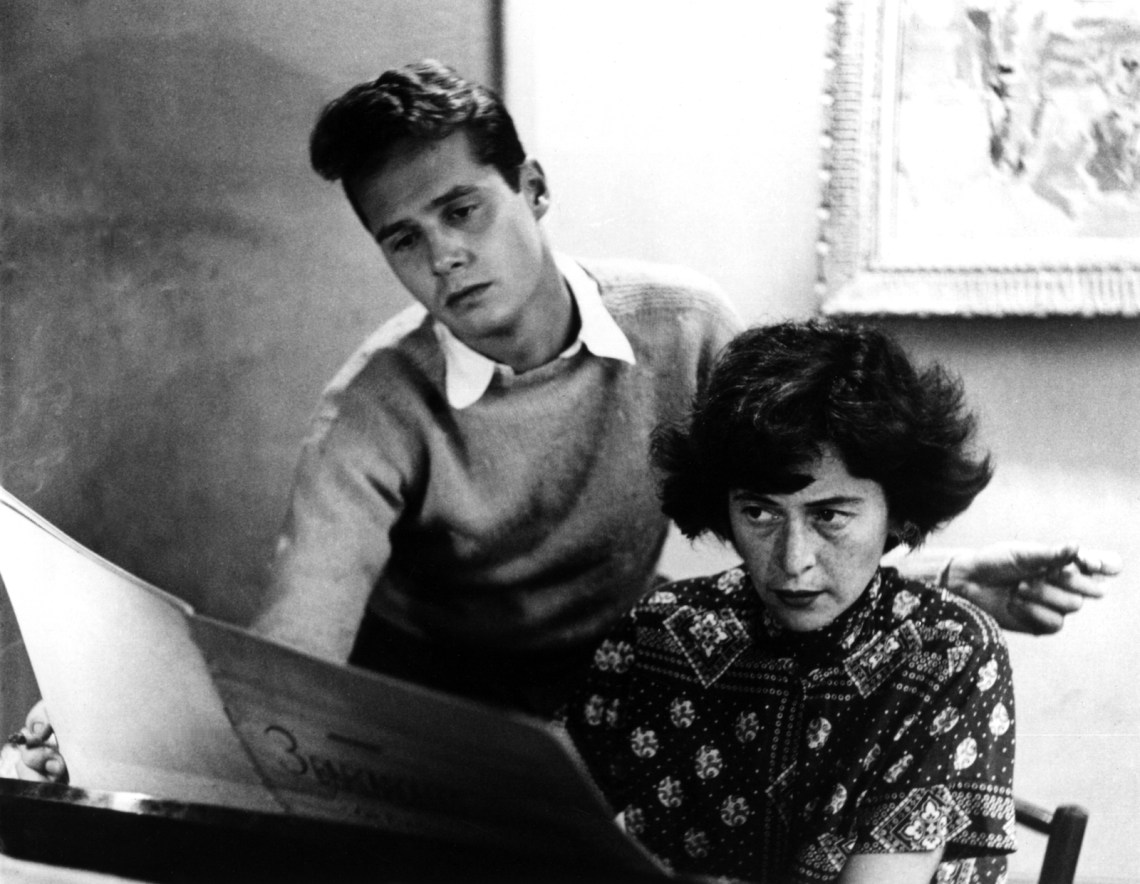

Looking for similar books in the Putney library I came across Rorem’s Paris Diary—first published, like Nin’s opening volume, in 1966—festooned with his handsome, evergreen face. I liked Rorem’s diary for some of the same reasons I liked Nin’s. For a straight sixteen-year-old like me, these writers wrote about sex with a certain exotic latitude. But while Nin’s writing was cerebral and off-putting—“No great love could take place in this wombless femininity,” she wrote of the gay poet Robert Duncan—Rorem famously described an avid gay life with aplomb.

In the decades since, Rorem has felt like a part of my life, a part of my sense of myself, for several reasons. For one thing, we came from the same Rust Belt town of Richmond, Indiana. Both of our fathers taught at Earlham College, a Quaker school, his in economics (Clarence Rufus Rorem’s later work in the economics of health care inspired the innovations of Blue Cross Blue Shield) and mine in organic chemistry. “We were Quakers of the intellectual rather than the puritanical variety,” Rorem writes in The Paris Diary, which seems true of my family, too. Though a generation apart, we were brought up with the same rules: “As Quakers we never used to stand for ‘The Star-Spangled Banner.’” Me neither. Shopping for children’s gifts with Stephen Spender, a pacifist, Rorem was surprised that Spender bought toy pistols. “We were never allowed guns.” My parents only relented when they discovered toy guns with UN Peacekeeping’s blue insignia.

Quakerism, as Rorem’s diary makes clear, is an orthodoxy like any other. Its strict tenets—nonviolence, rejection of official oaths and pledges, the Inner Light—are concealed beneath a veil of silence and a distaste for ritual. People who come to Quakerism late, attracted by its progressive political tendencies or its reticent creed, are sometimes surprised to learn that Quakers are, God help us, Christians. Rorem, who liked to drink (“I’ve spent a third of my life in sleep, a third in drink, a third vomiting”), compared Quaker services, “in form and content,” to AA meetings. He also likened them to Turkish baths as sites of “silent meeting,” though in the baths “the silence is shared solely by men, men who come uniquely together not to speak but to act.”

I first heard Rorem’s music at the Quaker colleges I attended, Earlham and Guilford, and then in New York during the 1980s, and I liked it for some of the same qualities—its immediacy, its emotional openness, its personal touch—that drew me to his writing. Rorem composed in many forms, but he was a master, like those other Hoosier songbirds Hoagy Carmichael and Cole Porter, of setting lyrics to music. “Any good song,” he wrote in The Paris Diary, “must be of greater magnitude than either the words or music alone.” I still prefer Rorem’s settings of Emily Dickinson poems—clear, poignant, not trying to do too much—to those of more “advanced” composers like Elliott Carter and Rorem’s sometime mentor Aaron Copland, which seem overbearing and suffocating for the oddly angled lyrics.

Rorem believed in giving words and melody a chance to breathe, and decried (a little crankily) the tendency among his highbrow contemporaries to treat the voice “not as an interpreter of poetry—nor even necessarily of words—but as a mechanism, often electronically revamped.” He thought the Beatles (whom he compared favorably, in a smart essay in this magazine in 1968, to Schumann and Poulenc) and Billie Holiday offered a better path to a musical future than the academic avant-garde of Pierre Boulez. “The Beatles’ words,” he noted, “often go against the music (the crushing poetry that opens ‘A Day in the Life’ intoned to the blandest of tunes).” As though to illustrate the point, Rorem composed two sharply divergent settings—one wistful and resigned, the other percussive and strident—of Dickinson’s quatrain “Love’s stricken ‘Why.’”

Advertisement

I encountered Rorem’s operatic version of Our Town (composed when he was eighty-two) when I was writing an essay about Thornton Wilder’s modernist masterpiece, a play disguised as a sentimental slice of Americana. Emily Webb has always seemed to me an obvious cousin of Emily Dickinson, one of Wilder’s favorite poets. In the setting of her emotionally overwhelming aria in the Grover’s Corners graveyard, in J. D. McClatchy’s libretto, Rorem found a kindred poignancy, plaintive and gut-wrenching, to Dickinson’s “stricken ‘why.’” “Goodbye to ticking clocks, to Mama’s hollyhocks,” Emily sings, “to coffee and food, to gratitude.”

I saw Rorem once, in Greensboro, North Carolina, when the Eastern Music Festival featured one of his pieces. He was wearing, if I remember right, a bright red shirt and a white jacket and he looked, as usual, dazzling. “Famous last words of Ned Rorem,” he wrote in The Paris Diary, “crushed by a truck, gnawed by the pox, stung by wasps, in dire pain: ‘How do I look?’”