Butterflies recur in Meret Oppenheim’s art: the many-eyed face at the top of her 1969 assemblage of painted canvas and carved wood, Hm-hm, its “nose” a shaped piece of bark; the tiny wings flitting at the edge of her ink and gouache drawing, Self-Portrait and Curriculum Vitae since the Year 60,000 BC (1966), the cross-section of an imagined geography, culminating in a flame-like floral burst. She was enthralled by the symmetry of butterflies, the mask-like quality of their open wings, and their symbolic promise of transformation—a potent metaphor for an artist who not only remade herself after early fame but kept doing so with every work, moving fluidly between assemblage, sculpture, collage, painting, and poetry, often in combination. “Every idea is born together with its own form,” she said. When, after her death, two of her friends found themselves in a cloud of butterflies, they both spontaneously shouted, “Hello, Meret!”

“Meret Oppenheim: My Exhibition,” her first major transatlantic retrospective, which has traveled from the Kunstmuseum Bern to the Menil Collection in Houston and, now, the Museum of Modern Art, highlights this diversity of styles, media, and moods. Beyond her two most emblematic and erotic Surrealist objects—her fur-lined teacup, saucer, and spoon, and her upturned white pumps trussed on a metal platter, both created when she was just twenty-two—are hundreds of highly varied works (the exhibition includes over 180) that nudge her artistic horizon in one direction or another. Together, they present a unity of vision: a sense of Oppenheim’s witty, receptive intelligence gradually enlarging toward the natural world and mythology. As Max Ernst wrote on the occasion of Oppenheim’s 1937 solo show in Basel, “Who covers a soup spoon with luxurious fur? Little Meret. Who has outgrown us? Little Meret.”

A Berlin-born Swiss artist, raised in the Jura Mountains and then in southern Germany, she was bicultural from the cradle and soon multilingual, and most of her early artistic education took place in Paris among the similarly international Surrealists.1 (Core artists associated with the movement came from all over Europe; Ernst was German, Salvador Dalí Spanish, René Magritte Belgian, Leonor Fini was Argentine-Italian, Toyen was Czechoslovakian.) Even in her early twenties she pushed back against André Breton’s notorious demands for allegiance. Anticipating his annoyance at her for attending a party with artists recently expelled from the movement, she insisted, “The thing that is most important to me is my independence and freedom.” Borders were made to be crossed and boundaries blurred.

By the time of her rediscovery in the 1960s she had homes in Paris and Switzerland, male and female lovers, and an artistic practice that required only a small toolkit and her mind. The writer Renate Stendhal, Oppenheim’s studio assistant in Paris in the 1970s, remembers her practiced state of receptivity while at work, “concentrated but loose, unfazed by interruptions.” When asked to explain her process, Oppenheim replied, “A voice tells me, ‘put a little grey here,’ et cetera, and I do it. I don’t judge.” She kept open her channels to the unconscious. A video clip from the 1980s shows her standing at her easel, beginning a painting with sweeping, confident brushstrokes. Only after she finished a work did Stendhal see her question the outcome, “unsure whether it’s good or bad or even what it is.”

*

Oppenheim was born in 1913 to a Swiss and German family with artistic and literary connections. Her niece, Lisa Wenger, describes Oppenheim’s parents as “very open to just about anything.” At fourteen she began to keep a dream journal, the start of a lifelong practice; when her father, a German psychiatrist, saw signs of depression in Meret years later, he arranged for her to consult their household god, Carl Jung.2 Meret’s maternal grandmother was a suffragist and a well-known children’s book author. Family friends included the Swiss Dadaists Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings and the writer Hermann Hesse, who was married for a few years to Meret’s aunt, the concert soprano Ruth Wenger.

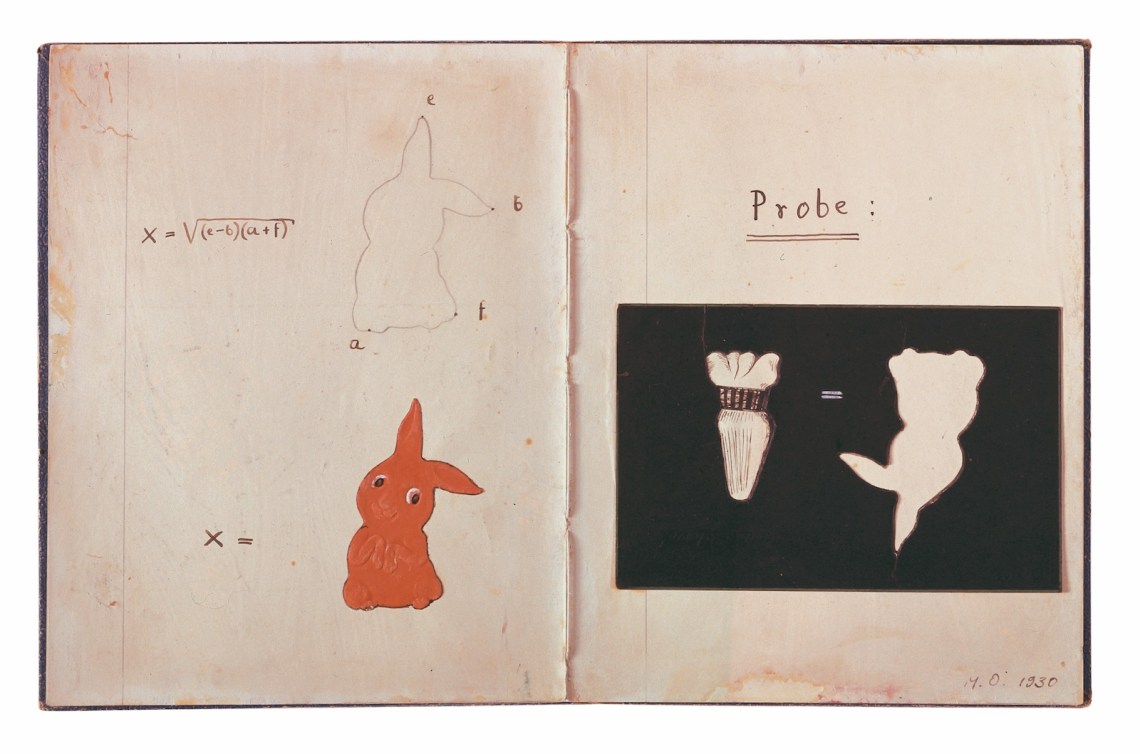

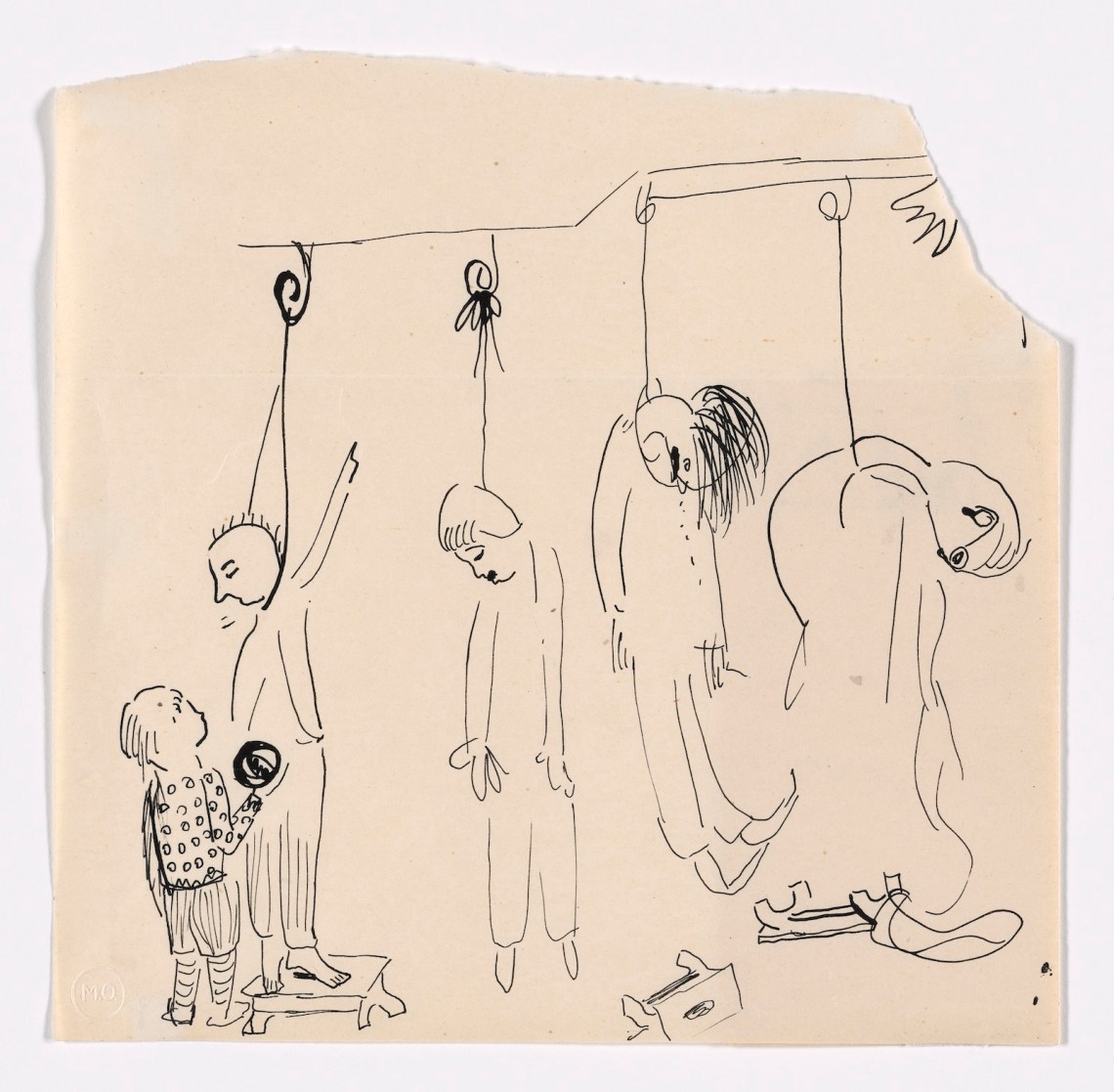

At sixteen, she won an argument with her father and was allowed to drop uncongenial subjects like mathematics in favor of art. Her opening gambit is preserved: a drawing, later titled “Schoolgirl’s Notebook,” with an algebraic equation in which X = a cartoon rabbit.3 Some early work suggests the influence of Paul Klee’s abstractions, which she had encountered at a 1929 Bauhaus exhibition in Basel. But the irreverence and mordant humor of Votive Picture (Strangling Angel) and Suicides’ Institute, drawn when she was seventeen, show why her friend the painter Irène Zurkinden joked that “if all the Surrealists got together and birthed a child, it would have been Meret.” In Votive Picture, the “angel,” striking a jaunty pose against a perfunctory hillside, has squeezed off an infant’s head; blood streams onto several feminine legs below, previous victims still wearing their stylish heels. The more blasé but equally macabre Suicides’ Institute depicts a row of roughly-sketched hanged people, with the next candidate poised on his stool, conversing with a child who seems to have wandered up, ball in hand, to observe the scene.4 Oppenheim and Zurkinden moved to Paris together in 1932, arriving tipsy from Pernod and rushing straight from the train station to the Café du Dôme in Montparnasse, the center of artistic bohemia, to immerse themselves in la vie surréaliste.

Advertisement

Although Oppenheim sporadically attended the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, a bare bones life-drawing studio in Montparnasse, she preferred to work in her room at the Hotel Odessa, amassing the sketches she would develop over decades into her major works. Her early work in Paris shows her sampling several of the powerful influences around her: Joan Miró, Hans Arp, Marcel Duchamp. “It’s not that I have any particular teacher,” she told her mother, “I have many, and there are many things I see and hear through them.” After meeting Alberto Giacometti at the Dôme she spent hours at his studio, unrequitedly in love, absorbing everything she could. He and Arp asked her to exhibit alongside them in the 1933 Salon des Surindépendents.

For the next four years Oppenheim was at the heart of the Surrealist circle, her gamine beauty and lack of inhibition as appealing as her small, enigmatic paintings and objects. She painted her first oil on canvas, Sitting Figure with Folded Hands (1933), with her fingers; in another work from that year, Walkers Behind Fence, she filled in the simple, chromosome-like outlines of her figures with peach-colored makeup. Two pieces of glued string constitute the fence. You feel these apprentice works as much as observe them, intuiting how her alertness to texture led her to bones and fur. Seated with Oppenheim at the Café de Flore in 1936, Pablo Picasso and Dora Maar admired a fur-covered brass cuff she was wearing, one of her projects for the fashion designer Elsa Schiaperelli. Anything could be covered in fur, the trio laughed, even a teacup. Shortly after, when Breton asked for an object to exhibit, Oppenheim bought a café au lait cup, saucer, and spoon and covered them with a scrap of “Chinese gazelle” she already owned.

In later years Oppenheim would give careful thought to the gendered concepts of artist and muse that were so potent for Breton and his circle, coming eventually to a radical synthesis, an androgynous ideal inspired by Jung’s archetypes. “A great work of literature, art, music, philosophy is always the product of a whole person,” she said in accepting the Art Award of the City of Basel in 1975, “and every person is both male and female.” But as a young artist in Paris she unconsciously embodied Breton’s dream of the free-spirited femme-enfant, modeling nude for Man Ray—most notably in his 1933 series Erotiques-voilée (Veiled Erotic), in which her inked body is laid on a printing press—and embarking on a yearlong affair with the much older Ernst, a rite de passage for almost every woman associated with the Surrealists.5 Her most assured painting of this period, Quick, Quick, The Most Beautiful Vowel is Voiding (1934), is dedicated to Ernst and features a dance-like procession of biomorphic shapes that look poised to tumble free of chained structures below them. She broke up with him suddenly, surprising them both. “It had been my instinct,” she realized long afterward, “the unconscious knowledge of imminent danger, that pulled me away from Max Ernst.” Becoming closer to a “completely mature” artist would have stunted her own development.

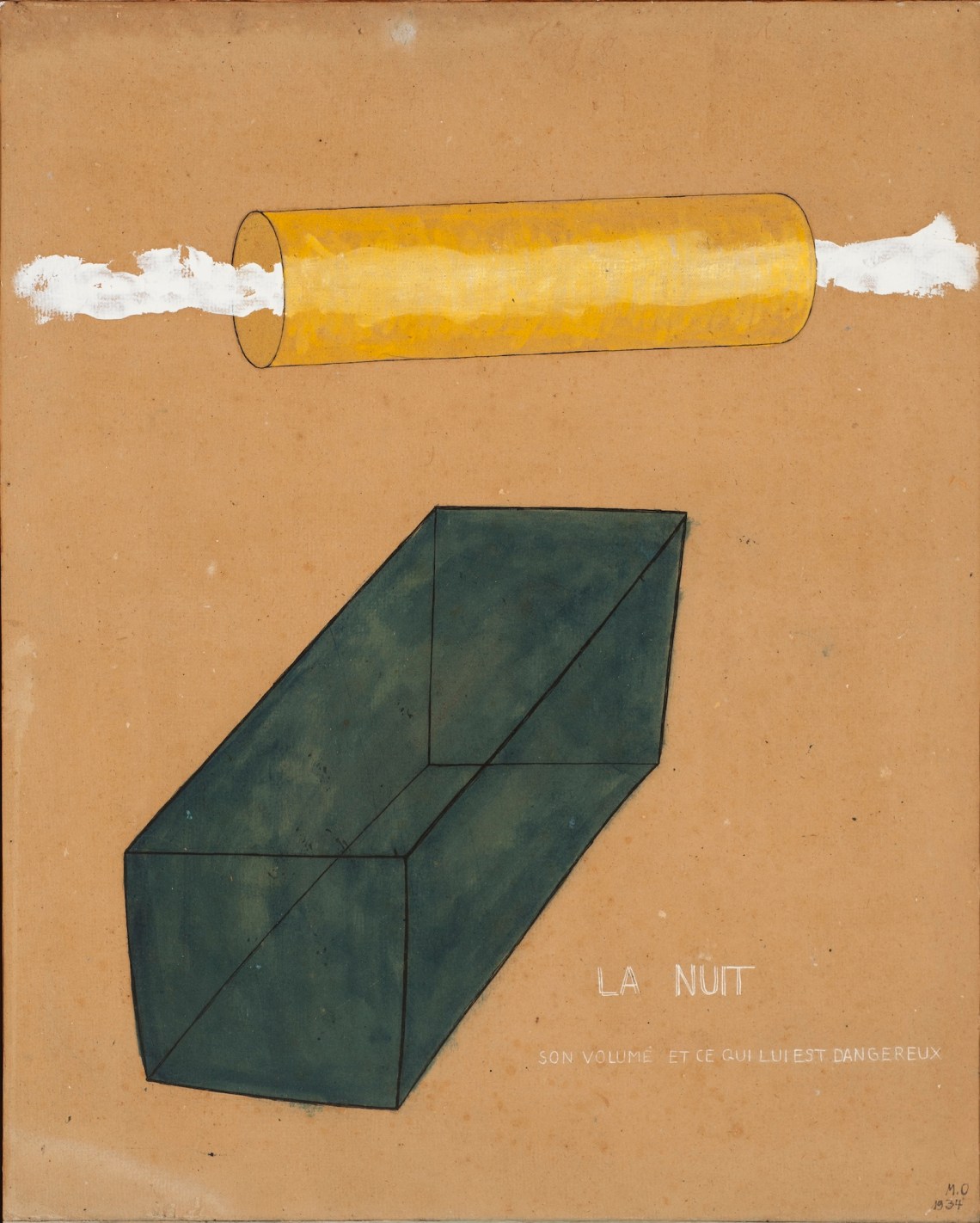

Where she held her own, from the beginning, was in poetry and wordplay. The title of The Night, Its Volume and What Endangers It (1934), for example, suggests a relationship between the painting’s semitransparent shapes—white plumes emerging from a yellow cylinder threaten to illuminate “night,” the dark rectangle below—but is fundamentally mock-serious, a mode that came easily to artists steeped in the German Romantics. Object, her original title for the fur-covered teacup, suggests a bland curatorial label in a provincial museum. It underscores the shock of the piece: not only its uselessness, reflecting the Surrealist determination to strip use value from commodities in favor of symbolic meaning—as in Ray’s The Gift (1921), a flat iron with fourteen thumb tacks glued to its plate—but also the visceral pleasures conveyed by sheathing a set of domestic items associated with women in the pelt of a prey animal.6

Advertisement

Like automatic writing, the Surreal object provides a means to mine the unconscious for jarring new truths, the better to subvert bourgeois values. What was hidden would be revealed, just as Freud had brought to light the unseemly thoughts and urges behind even the most respectable facades.7 The most successful objects pass a sensory charge to the viewer: we imagine answering Dalí’s clammy Lobster Phone (1938) or sipping—in dread or delight—from the fur-covered cup. Breton retitled it “Le Déjeuner en fourrure,” recalling both Édouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863) and Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s novella Venus in Furs (1870), but his joke feels heavy-handed.

The piece caused a sensation.“The ‘fur-lined tea set’ makes concretely real the most extreme, the most bizarre improbability,” wrote Alfred H. Barr Jr., founding director of the Museum of Modern Art. In June 1936, a month after its debut at Breton’s exhibition of Surreal objects in Paris, the cup appeared at the London International Surrealist Exhibition—a mob scene with some 24,000 visitors—and then at MoMA that winter, at Barr’s exhibition “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism,” where it is said that a woman fainted on viewing it. Barr bought Object for fifty dollars in 1937, the first work by a woman purchased for MoMA. The museum rarely exhibited it until the 1960s, perhaps hoping to forestall responses like that of Robert Hughes, who described it as “the most intense and abrupt image of lesbian sex in the history of art.”

*

Political turbulence in Europe and the loss of her father’s income, the Nazis having forbade those of Jewish heritage to practice medicine, forced Oppenheim to leave Paris in 1937 and rejoin her family in Basel. The contrast between her Paris idyll and her conservative home city, where she could not wear unmatched socks without attracting disapproval, was exacerbated by the financial and travel constraints of the war and her sense of isolation. She fell into a creative crisis that lasted seventeen years, during which she destroyed much of her work. Every failure felt inevitable: “I felt as if millennia of discrimination against women were resting on my shoulders, as if embodied in my feelings of inferiority.” Stone Woman (1938), which draws on Ray’s 1933 photograph Pebbles, is often read as a self-portrait of this bleak period, an armless female figure in hard pieces washed up on shore. “The only really positive thing,” the artist later wrote, “is the feet, which represent a connection to the unconscious.”

The many works from the late 1930s and 1940s included in “My Exhibition” make clear how productive she remained during this time, visually recording her depression. These new paintings benefited from technical expertise she acquired from a two-year art restoration course in Basel and show an increasing sensitivity to nature and the use of natural materials, especially those picked up on forest walks near her family’s home in Carona. Fresh inspirations, like Malagan sculpture, surface. She found a political outlet with the antifascist art collective Gruppe 33, exhibiting with them from 1939 on, and married a businessman, Wolfgang la Roche, in 1949, who shared her adventurous spirit and took her on long motorcycle rides throughout Europe. Each year, she created costumes for Carnival in Basel, a channel for her continuing interest in wearable art and her love of masks and revelry. A friend remembered a stunning example:

She dressed up as an elegant lady, her face covered by a pretty mask. After some flirtation, she would suddenly drop the mask, revealing a bloody, deformed, skinless face. She had sewn pieces of steak onto a tight-fitting gauze mask. Periodically she moisturized the meat with a vaporizer to keep its gruesome appearance.

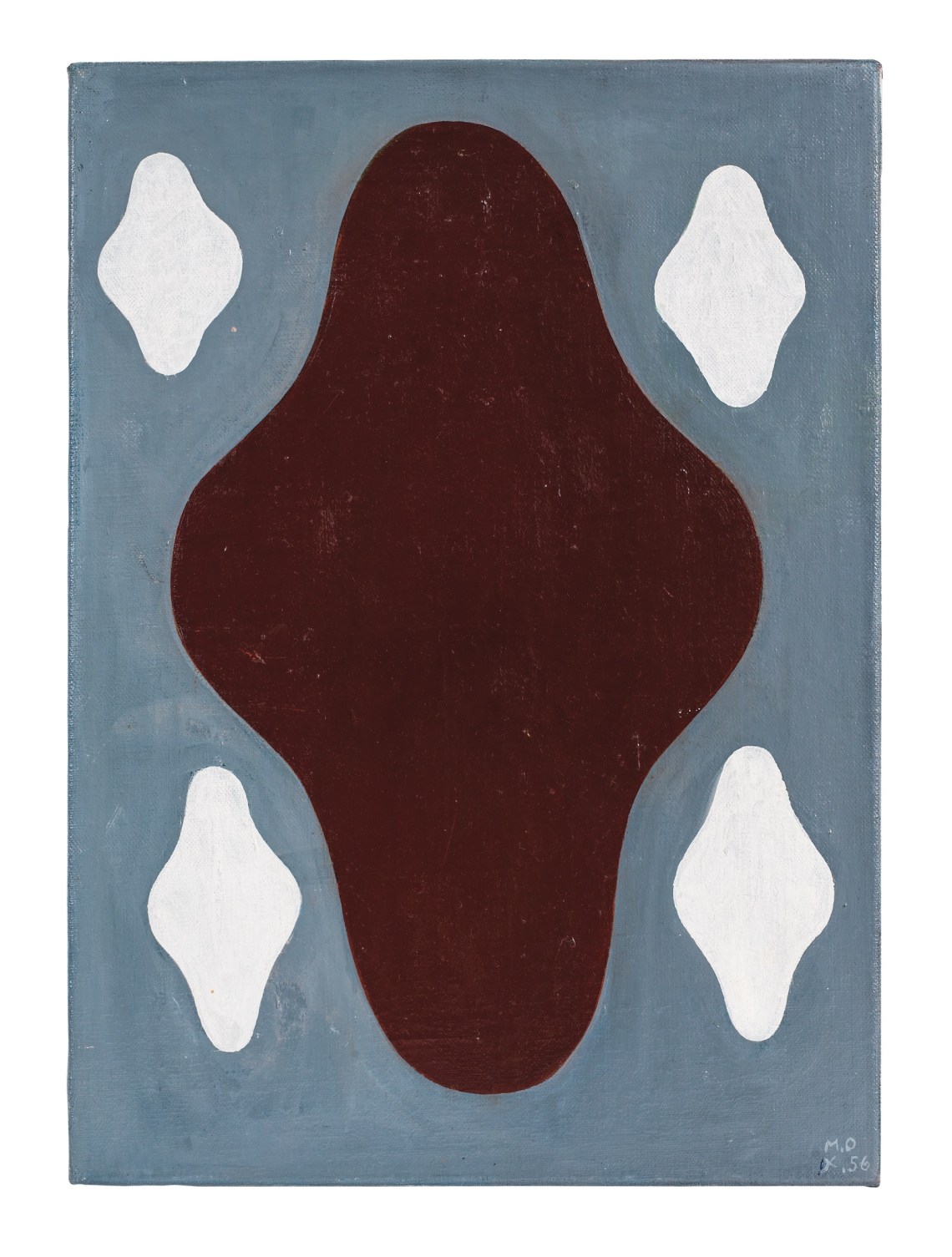

She was attracted to tales of metamorphosis and transformation, like that of Daphne and Apollo. (In her version, painted in 1943, Apollo is as much transformed as Daphne—a sensual pink tree—but gets the worst of it, morphing into a potato-like trunk with tapering, useless limbs.) But she also kept returning to the story of Genevieve de Brabant, a medieval heroine from the Golden Legend unjustly exiled to the forest with her infant son after a false accusation of infidelity.8 She first depicted Genevieve in 1939, floating among clouds in The Suffering of Genevieve, painted in what she described as her “romantic-anecdotal-illustrative” style of that period and alluding to Ernst’s collages.9 In 1942 she sketched the idea for a minimalist sculptural treatment, a wooden panel with two sticks for (broken) arms, which she would realize in 1971. Then, in 1954, a powerful dream—a rabbit leaping across a snowy landscape—inspired her to shake off her depression. Genevieve returned as a simplified black shape, a biomorphic lozenge, in Genevieve and the Four Echoes (1956) and Genevieve Hovering Over Water (1957)—signaling a move into geometric abstraction that would eventually lead to the hard-edge painting of some of Oppenheim’s large, late work.

Oppenheim visited Paris before the war started, to exhibit in a show of fantastic furniture with Leonor Fini and others, but it would be a decade before she returned again. Meeting old friends, she had the sense that she had changed more than they. The teacup, meanwhile, was becoming an albatross. Daniel Spoerri, a younger friend from Bern, remembers the difficulty Oppenheim had in re-establishing herself in Switzerland: “People didn’t really know much about her and were only familiar with her ‘fur cup.’” Through the 1950s she occasionally published in Surrealist journals and co-signed Breton’s tracts, but she stopped using the term “Surrealist.” “I hate labels,” she said bluntly in 1984, but clarified,

I think that what Breton said about poetry and art in the first manifesto in 1924 was more beautiful than anything else that has been written on the subject. By contrast, just the thought of everything that is associated with Surrealism today makes me feel ill.

Her disaffection was also personal. She finally lost faith in the movement after a bruising episode in which she allowed Breton to recreate her 1959 performance piece, Spring Banquet, a meal among friends served on a nude woman’s body. Her version had been woman-centered and nurturing; his felt exploitive and objectifying. By then her work was gaining traction in contemporary European art circles, and she resented being pulled back into her famous past. “Journalists ask me about relationship with A, B, and C, etc.,” she wrote. “No one asks me about my relationship with raw umber.”

This imbalance shifted in the 1970s when American feminist scholars began to investigate the women of Surrealism, then all but erased from art history. Characteristically, Oppenheim had mixed feelings about being classified as a woman artist. Art was androgynous, she argued. But she welcomed the critic Gloria Orenstein’s challenges to Breton and Benjamin Péret’s concept of the femme-enfant, which assigned intellectual power to male artists and a dreamy, alien irrationality to young women. Women over thirty scarcely registered for the Surrealists, as Oppenheim had realized when her male friends stopped sitting with her at cafes. Archeological work on matriarchal religions and the burgeoning Goddess movement—a new mythology of a neolithic matriarchal age that preceded patriarchy—gave impetus to much of Oppenheim’s art of the 1970s, including her masterpiece Old Snake Nature, a monumental coiled serpent covered in glistening anthracite and barely contained by a burlap sack. In Oppenheim’s retelling of the biblical tale, “the snake Nature wanted man to take the path of intellectual development,” but he declined, condemning Eve and Nature. Now it was time to change direction, honoring women and the earth and achieving “true wisdom for once.”

Each major posthumous exhibition has taken another step in untangling Oppenheim from Surrealist legend. “My Exhibition” is the first to include the meticulous drawings she made in 1984, the year before her death, for an imaginary retrospective, offering insight into how she viewed her own evolution as an artist. She remarked that hers was only one possible selection and arrangement. She remained open to interpretation—though the task is not easy. “Are you Alice in Wonderland?” one interviewer asked her. “No. I am the looking glass,” she said.