I got a real break in 1963. I’d been living in New York for a year and had just moved from a rooming house on St. Mark’s Place to an apartment on East Sixth Street, across from Tompkins Square Park. I paid eight dollars a week at the rooming house and sixty a month for the apartment. No longer did I have to share a bathroom with other tenants. The food was cheap: for less than three dollars a day you could get by on knishes and Ukrainian cabbage soup. I was working a temporary job as a claims clerk at the New York Department of Labor, one of the many jobs I had while writing poetry. I was twenty-five. Sometimes Bob Kaufman, the great Beat poet, slept on my floor. He was homeless.

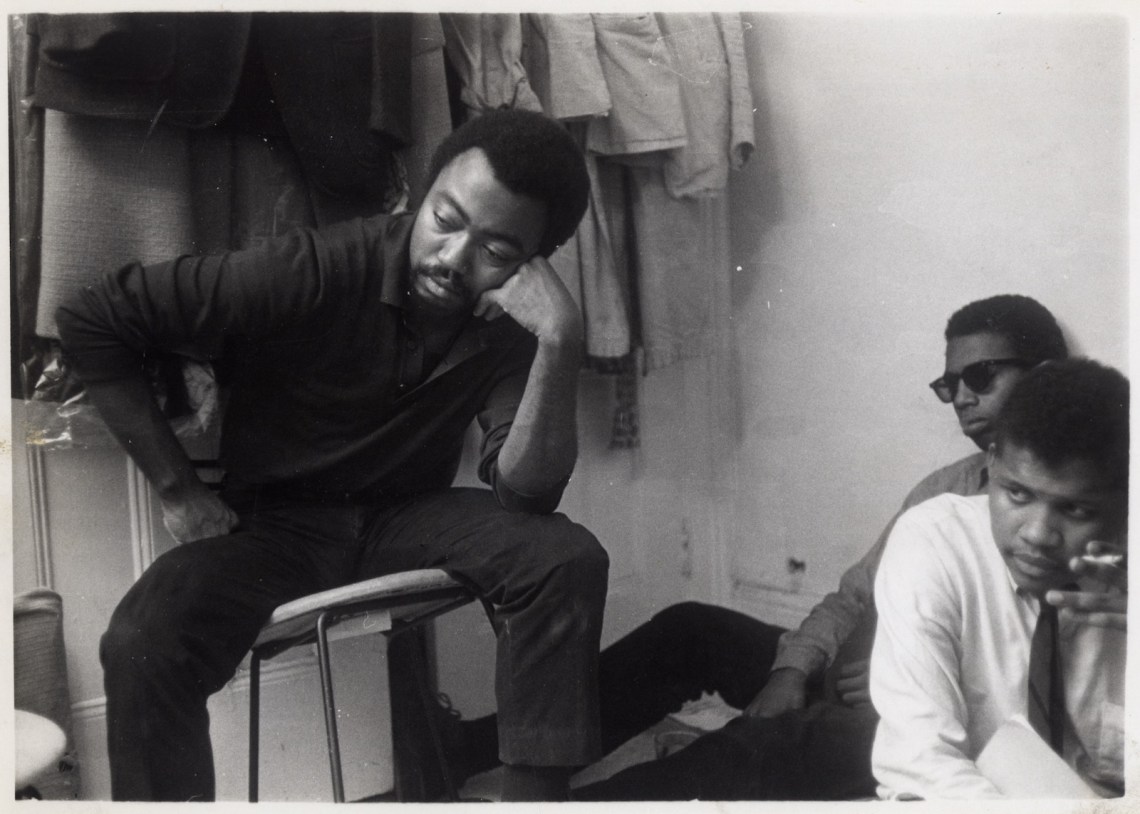

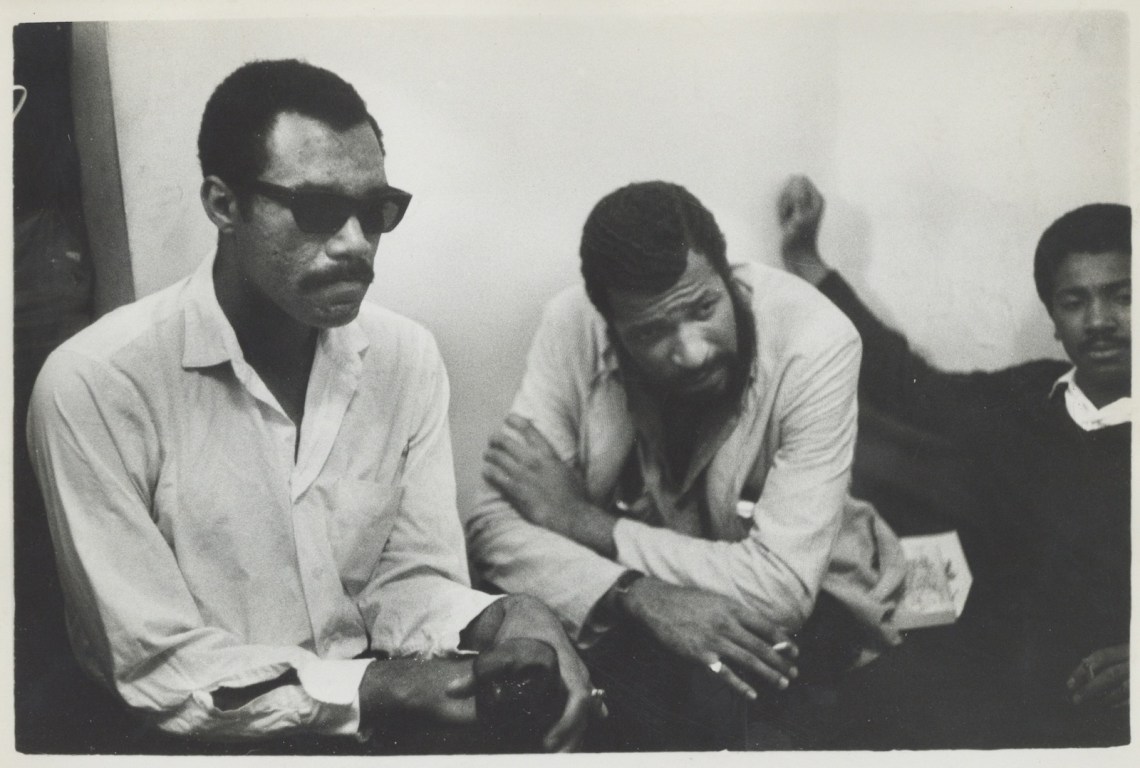

Someone told me about a writer’s workshop called Umbra. The group met in the East Second Street apartment of its cofounder Tom Dent, and I showed up to my first meeting in the spring of 1963. Present that evening were Lorenzo Thomas, Askia Touré, Charles Patterson, David Henderson, Albert Haynes, and the workshop’s cofounder Calvin Hernton—Black writers who would become pioneers of the Black Arts Movement (BAM). Missing that night was another influential Umbra writer, James Thompson.1

Dent, who was working for the NAACP and had belonged to the Black nationalist literary organization On Guard Committee for Freedom, had a pedigree. His father was Albert W. Dent, president of Dillard University, whom I would visit in New Orleans in 1976 to cover Mardi Gras for Oui magazine. Albert Dent could pass for white. His beginnings were humble, but he rose to the top of the Black aristocracy. He told me he was the first Black person to be admitted to the Rex Krewe, at the top of Mardi Gras balls. At Dillard, he had brought Martin Luther King, Jr. to campus. Because of his connection with the elite of the civil rights movement and Tom’s own job with the NAACP, stars like James Meredith, Charlayne Hunter-Gault, and Reverend King’s brother came to the workshops.

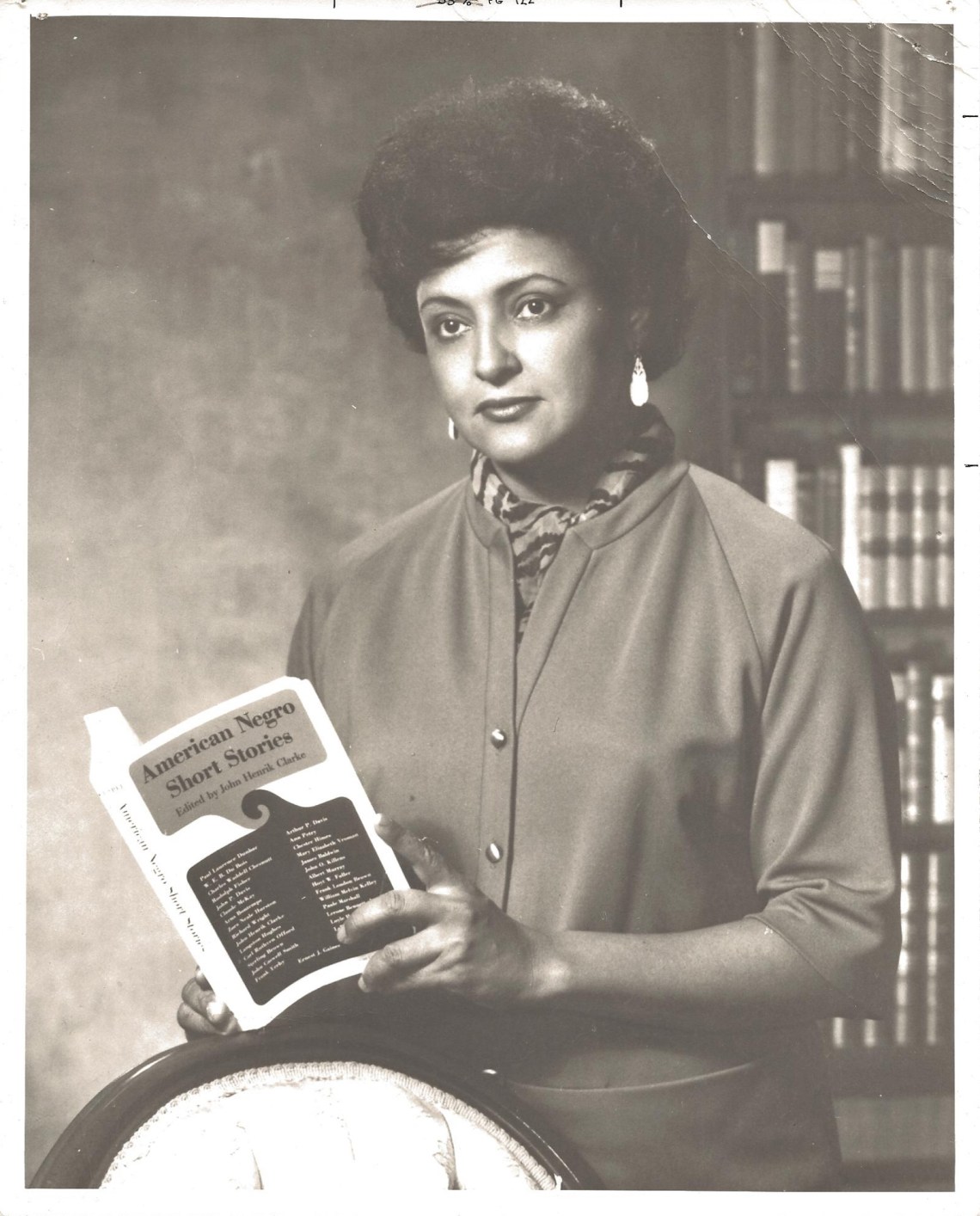

Tom Dent also brought Jane Logan Poindexter, a Doubleday editor who in 1965 would be responsible for publishing Hernton’s first nonfiction book, Sex and Racism in America. She, Brenda Walcott, the late Maryanne Raphael, and the late Amhara Hicks were four of a handful of women who attended Umbra. In those days, writing was viewed as a male art, but some women, including the playwright Aishah Rahman, overcame the movement’s patriarchal bent. The Lower East Side, she remembered in a memoir about these years for my magazine, Konch, “was roiling with arts and politics and music.”2

During the usual Umbra meetings, writers read their work and the rest of us commented. Sometimes the comments were harsh, based on both political differences and aesthetic ones. Joe Johnson—who would later become my partner in the publishing company Reed, Cannon, and Johnson—never liked my poetry, while Hernton encouraged me. At one meeting, the tensions between integrationists and Black nationalists boiled over and William Patterson gave David Henderson a bloody nose.

At the time, I was writing pretentious imitations of Yeats and Pound because Black writers had been absent from the school curricula imposed on us. I had read James Baldwin in Buffalo before moving to New York, not in school but because I’d worked at a library. It was through Umbra that I met many Black poets, including Langston Hughes, who published my poetry and that of my Buffalo friend Lucille Clifton, whose work I introduced to him. The poet Gloria Oden patiently listened to me read from my first novel. I didn’t read much Black fiction until 1968, when I was asked to teach a fiction course at the University of California at Berkeley. I was a visiting lecturer. The “visit” lasted thirty-five years.

After the workshops, Umbra members adjourned to Stanley’s, a bar and restaurant on Avenue B frequented by actors, poets, painters, and musicians. The Polish American owner, Stanley Tolkin, tolerated the patrons, a mix of Black cultural nationalists and white counter-culture types. He was such a fabulous character that the Polish author Jan Błaszczak wrote his biography, for which he is still seeking an American publisher. I straddled the two scenes, contributing to Black nationalist publications like The Cricket and The Liberator and cofounding The East Village Other, one of the first underground newspapers.

For a time, poetry readings were held at a café called Le Metro. As I have written elsewhere, the owner, who had a GOLDWATER FOR PRESIDENT sign in the window, had hired some thugs—they might have been in the mob—to keep an eye on the Black men who showed up to read. We saw Goldwater as someone who applied a sheen of dignity to a racist movement. I don’t know what led to the fistfight, but one of the thugs punched Tom. I went to Tom’s aid, and they punched me too. The Black writers left. I was returning to a Second Avenue apartment with my girlfriend when I decided to return to the café. I was allowed in. I approached my collaborator, the poet Walter Lowenfels, who was reading, and demanded he stop because the owner was a fascist. Walter ended his reading. Everybody left. That was the end of the readings at Le Metro. The Black Mountain poet Paul Blackburn and I spent the weekend looking for another site, and the rector at St. Mark’s Church told us we could hold our readings there. Those were the roots of the St. Mark’s Poetry Project, which the Project itself didn’t acknowledge until a few years ago.

Advertisement

Amiri Baraka, then LeRoi Jones, lived at 27 Cooper Square. His friends were among the downtown white arts elite, painters and poets, among them Frank O’Hara, who mentions Baraka in “Personal Poem” (1960):

I walk through the luminous humidity

passing the House of Seagram with its wet

and its loungers and the construction to

the left that closed the sidewalk if

I ever get to be a construction worker

I’d like to have a silver hat please

and get to Moriarty’s where I wait for

LeRoi and hear who wants to be a mover and

shaker the last five years my batting average

is .016, that’s that, and LeRoi comes in

and tells me Miles Davis was clubbed 12

times last night outside BIRDLAND by a cop

Because of his mentor Allen Ginsberg’s publicity connections, the New York Herald Tribune declared Amiri the “king of the East Village,” putting him at the center of a “personality cult” of the kind that Askia Touré argues white critics have long imposed on Black literature. A recent article in The New York Times, whose coverage of Black culture is often careless, stated that Baraka was “the founding father of The Black Arts Movement.” He was no such thing. To his credit, he rejected his role as a token; he said BAM was founded by a collective. He encouraged younger writers, including me.

Between 1963 and 1965, Baraka’s poetry began changing under the influence of Touré, Larry Neal, and Yusef Rahman. “Word from the Right Wing,” included in his 1969 collection Black Magic: Poetry 1961-1967, begins by playing “the dozens” on the then-president:

President Johnson

is a mass murderer,

and his mother,

was a mass murderer

and his wife

is wierd looking, a special breed

of hawkbill cracker

and his grandmother’s

wierd dumb and dead

turning in the red earth

sick as dry blown soil

I was critical of his early work. He never forgave me. Yet he was also critical of that work, which he admitted was influenced by a downtown white aesthetic. “You notice the preoccupation with death, suicide, in the early works,” he wrote in Black Magic about his first two books, Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note (1961) and The Dead Lecturer (1964). “Always my own, caught up in the deathurge of this twisted society. The work a cloud of abstraction and disjointedness, that was just whiteness. European influence, etc., just as the concept of hopelessness and despair, from the dead minds the dying morality of Europe.”

*

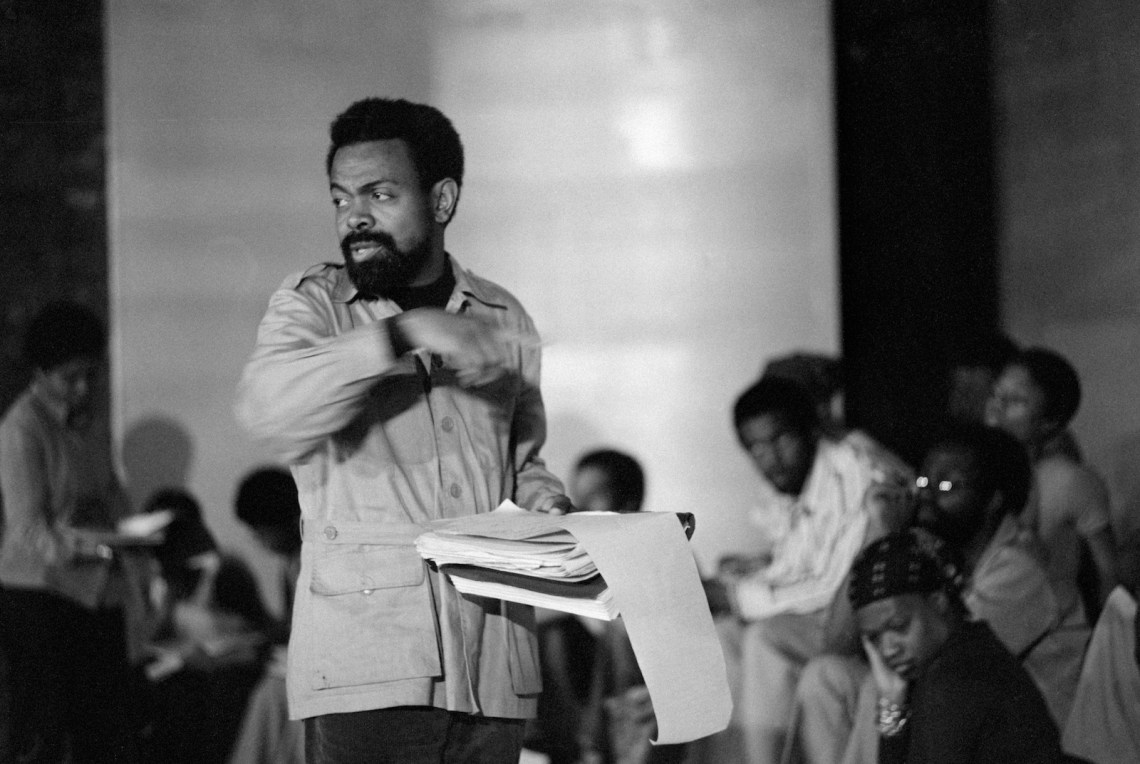

I never saw Baraka at Umbra meetings, though I went weekly, but he later wrote that the workshop was the cradle of the Black Arts movement in New York. If the poetry later gathered in Touré’s collection Dawnsong! was the manifesto of Black Arts, urging the use of African kingdoms of the past, especially Egypt, as sources of poetic inspiration, the afterword to the 1968 anthology Black Fire—edited by Baraka and Neal, the philosopher of the movement—states its aims.3 There Neal called for independent literature, free of white patrons. “The so-called Harlem Renaissance was, for the most part, a fantasy-era for most black writers and their white friends,” he wrote. “For the people of the community, it never even existed. It was a thing apart.”

Whereas many writers of the Harlem Renaissance (with exceptions like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston) wrote in a lofty diction and fiction writers of the 1950s used Hemingway, Faulkner, and Henry James as models, Black Fire repudiated what the poet Etheridge Knight called “the white aesthetic” in favor of Black English. Echoing the Harlem Renaissance writers who called themselves “the New Negro,” Neal spoke for “the New Breed.”

Advertisement

Neal wrote that people saw James Baldwin as “another form of entertainment.” Having taught Baldwin’s books, I can offer that most of his fans haven’t read them but only know him from his televised debates and comments. Baldwin has the edge over his current imitators because he worked with the Actors Studio. It was such a bad experience that he satirized Lee Strasberg in his novel Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone (1968)—an insult over which the New York “Family” ostracized him. After Richard Wright used his influence to get Baldwin a fellowship, Baldwin criticized Wright under the direction of William Phillips, the coeditor of Partisan Review. (An anti-Stalinist, Phillips disagreed with the Chicago left Wright represented, which had proletariat leanings.) In his famous encounter with Wright in Paris, related by Chester Himes, Baldwin said that “the sons must slay their fathers.” That kind of literary parricide and matricide still seems to be taking place in New York.

The New Breed was competitive, too, but we had an option that the previous generation lacked. Thanks to advances in technology, Umbra taught us how to print books and edit anthologies. During the first phase of its existence, the workshop published two issues of a self-titled magazine in which celebrities like Julian Bond and Robert F. Williams appeared alongside young and unknown writers like Thomas, Touré, Henderson, Hernton, Johnson, Dent, Baraka, Kaufman, LeRoy McLucas, Lloyd Addison (who gave Umbra its name), Conrad Kent Rivers, Jayne Cortez, Nikki Giovanni, Tom Weatherly, Jay Wright, and me.

Those writers were dismissed by white critics. Reviewing the spoken-word album Destinations—which included Hernton, Blackburn, Jerome Badanes, and the Umbra member N. H. Pritchard—Robert Mazzocco wrote for this magazine that Pritchard “has a vocational delusion large enough to fill in the Grand Canyon.” Pritchard, a poet then in his mid-twenties, introduced me to my wife, the choreographer, director, and author Carla Blank. We were all collaborators in a 1965 multimedia show called “Black” directed by the late Aldo Tambellini, first at Columbia University’s International House and then at the Bridge Theater on St. Marks Place. Now, as a result of his ties to the Language poets, the Pritchard renaissance is in full swing.

Drama and poetry were the primary forms of expression during this period. “The best of the work that the Movement engendered qualify as masterpieces that will endure for generations,” the poet A. B. Spellman wrote to me in August. He cited Baraka, Sonia Sanchez, and Amus Mor, “perhaps the greatest stand-up poet I have ever seen.” It was Black Arts writers, he said, who “pioneered contemporary performance poetry.”

BAM poets included performance elements into their work to a greater degree: Mnemonics, rhythmic cadences, sometimes movement, and they rehearsed with the jazz ensembles with which they performed…Yes, I know that they were not the only artists to do so, and I would not diminish such great artists as Laurie Anderson, but I am confident in my recollection that BAM poets woke the medium up.

The German-born Harvard scholar Werner Sollors told me he remembered hearing “a particularly intense poetry slam in the Riverside Church in the 1970s.” He said it was a time when

sharp political notes and strong articulations of black pride found expression in modernist forms, in surrealist, expressionist, and Beat-inspired idioms. There were many new publications, some in pamphlet form, but texts seem to become less important than their performance, and one had a feeling of freedom.

Spellman also stressed the movement’s contributions to jazz—“a fundamental BAM expression”—and visual art. William White was BAM’s official illustrator. He and I were clerks at the Tri-State Transportation Commission, which was conducting a survey of traffic arriving in New York. Also employed there was Walter Bowe, who was later arrested in a plot to blow up the Statue of Liberty. There were clerks who said that they’d belonged to Mossad. Yet it was a quiet place to work. People were polite.

The painter Joe Overstreet had the idea of bringing musicians like Albert Ayler and Sun Ra uptown using flatbed trucks to reach Harlem neighborhoods with their music, along with plays by BAM playwrights. Other Black painters depended on white gallerists for recognition, but in 1974 the Overstreets established their own venues, Kenkeleba House and The Wilmer Jennings Gallery, on East Second Street. Corrine Jennings continues to run them after her husband’s death. Overstreet’s 1970 abstract painting HooDoo Mandala, as Jeff Chang has pointed out, was a source of inspiration for the “Neo-HooDoo Manifesto” I published the same year. The manifesto was a summary of my research after discovering that African religion had survived the slave trade. Though driven underground in the United States, it is so prominent in Cuba, Brazil, and Haiti that it competes with the Catholic Church.

*

Collaboration between Black and white artists started falling apart after events like the bombing of Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church in 1963, which killed four Black girls, and Malcolm X’s assassination in 1965. The painters and musicians remained downtown, but many of the Black writers left the East Village. Bill Amidon described the breakup of the Avenue B scene in his classic 1972 essay for The Village Voice, “Where Have All The Hipsters Gone?”

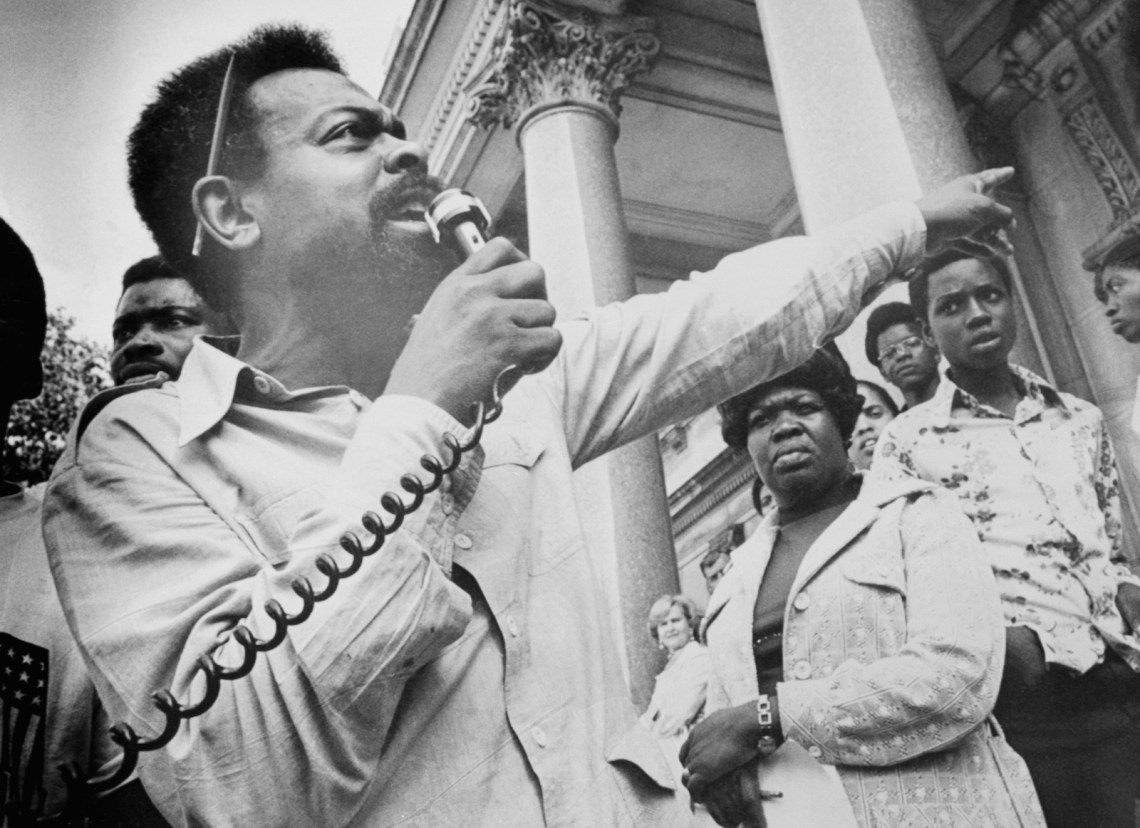

In 1965 Baraka had a much-publicized break with his Jewish wife, Hettie Jones, and moved to Harlem. There he and others founded the Black Arts Repertory Theater/School (BARTS)—a center where the Black aesthetic could be practiced in theater, poetry, painting, and music—and vilified those who hadn’t followed his example. His condemnation of the integrated Lower East Side created a breach between the uptown and downtown artists. Hernton and I donated our time to fundraising events for the school, but Baraka writes in The Autobiography of LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka—a brilliant, soul-searching book that might be his best work—that he’d wished harm would come to us because we continued to live on the Lower East Side.4 He and the BARTS cohorts opposed “race mixing” and threatened those involved in interracial relationships—although in her memoir Jones remembers him encouraging a polyamorous arrangement involving her and his girlfriend Vashti.

Three former members of Umbra joined Baraka in Harlem: Askia Touré and William and Charles Patterson. I had shared an apartment with the three of them on East Fifth Street, where I paid the rent for a while. I moved out because we were supposed to take turns paying. It didn’t happen. I heard a lot of Black Arts talk around the apartment, so I wasn’t surprised when they moved uptown. In his autobiography, Baraka claims that the Patterson brothers—he calls them the Hackensacks—destroyed the Black Arts experiment by alienating major players in the Harlem community, sometimes with violence. “There were more people wanting to kick the two Hackensack brothers’ asses,” he wrote, “than you could kill with a submachine gun without a lot of extra clips.”

The FBI spied on the Black Arts Repertory from its fundraising phase, where my name comes up, until its collapse due to sometimes violent disputes in March 1966. “FBI spies attended BARTS’s summer education classes, sitting in on Harold Cruse’s groundbreaking Afro-American history course,” the scholar William Maxwell has written. “Baraka himself believed that the early breakup of BARTS was caused in part by FBI tampering.” But it was not only the FBI and the internal divisions that caused Baraka to leave Harlem. Gus Newport, the former mayor of Berkeley, told me that Baraka also ran afoul of the crime boss Ellsworth Raymond “Bumpy” Johnson, “The Harlem Godfather,” when he demanded that one of Johnson’s friends fire a white waitress from his coffee shop. According to Newport, Baraka left Harlem the next day.

He left BARTS in chaos. In March 1966 the police traced Charles Patterson to the theater after he shot Neal in the leg. He raised a gun against the police and a shot was fired. Rumor has it that Black officers kept him from being killed.

*

Toward the end of the 1960s, some of the Umbra poets dispersed. Lorenzo Thomas settled in Houston. Tom Dent returned to New Orleans and became an important member of the Free Southern Theater. Touré also headed south, where he cowrote SNCC’s 1966 Black Power position paper. After a sojourn in London, Hernton became a distinguished professor at Oberlin College, where his students nicknamed him Socrates. He wrote a surrealist novel about the London journey called Scarecrow (1977), which Doubleday could not sell. I bought the remainder and sold them over the course of ten years.

Although the school had burned out in less than a year, the idea of Black populist art had spread. “By the end of 1965,” Baraka wrote later, “there were similar efforts rising all over the country.” Haki Madhubuti, whose Third World Press celebrated its fifty-fifth anniversary last year, has written that “if the East Coast represented the heart and soul of the Black Arts Movement,” the Midwest was its “intellectual center.” He singles out the Chicago-based Negro Digest/Black World, edited by Hoyt W. Fuller, which published both “Black mainstream writers and the new and upcoming poetic voices of BAM.” In New Orleans, Kalamu ya Salaam and Tom Dent’s BLKARTSOUTH published a journal, Nkombo, and organized theater performances across the region.

Using the Black Arts model, Quincy Troupe’s Black Roots Festivals, held in New York, attracted huge audiences. The poet and professor Eugene Redmond’s BAM St. Louis has nurtured three generations of writers. In his important book Drumvoices, Redmond showed that enthusiasm for Black writing sprouted throughout the country during these years, whether or not it went by the name Black Arts.5 Redmond has championed the work of the poet and fiction writer Henry Dumas, whom a New York policeman murdered in 1968.

I went west, where I became an editor of a multicultural magazine, Yardbird Reader, and founded the Before Columbus Foundation in 1976 and PEN Oakland in 1989, both coalitions of Black, Native American, Hispanic, Asian American, Jewish, Irish, and Italian American writers. (Our American Book Awards are among the only major awards that Audre Lorde, Andrea Dworkin, and Paule Marshall received during their lifetimes.) In 1973 I cofounded a small press with Joe Johnson and Steve Cannon, both former members of Umbra.

If Baraka was the king of the East Village, the late Steve Cannon had become the emperor. Three generations of writers passed through his workshops and galleries before his death in 2019 at eighty-four. Cannon and the staff at his organization, A Gathering of the Tribes, produced a multicultural magazine called Tribes and started an art gallery generously supported by the artist David Hammons and other patrons. When I sat in Steve’s living room, out of which he ran his operation, I never thought that it would be duplicated in an installation at the 2022 Whitney Biennial.

At Yardbird Reader we published many writers who are now part of the canon. Among them were Ntozake Shange, Thulani Davis, and Jessica Hagedorn, who lived in San Francisco until they went to New York and became famous. They referred to themselves as “The Satin Sisters.” An excerpt from Ntozake’s novel Sassafrass, Cypress & Indigo (1982) that appeared in Yardbird in 1975 has all the features one associates with a Shange work: a variety of formatting angles and an excursion through the Black avant-garde, which includes names of musicians, dancers, and political figures. The excerpt ends with recipes. In her poem “Parable,” which appeared in Yardbird 5, Davis writes that “the shrewdness of hurt women/can grab you in the night/and roll you like a trick.”

The Seventies saw the ascent of a younger generation of Black women writers: Shange, Davis, Toni Cade Bambara, Mari Evans, Alice Randall, Jill Nelson, Toni Morrison, Carolyn Rodgers, Mae Jackson.6 (Preceding them were Margaret Walker, Louise Meriwether, Gwendolyn Brooks, Gloria Oden, and Sarah Webster Fabio, who has been called “the mother of Black Studies.”) The masculinists who’d spent volumes criticizing The Man and celebrating ancient African queens found themselves under fire for resembling The Man themselves. The Black Arts men were not alone in their attitude toward women (Lynnette Lounsbury has written that the men of the Beat generation treated women “like cardboard cut-outs”), but there had been misogyny at BARTS. Sonia Sanchez told me during a recent interview that she and two other women who were preparing a curriculum there were threatened by two men who wanted to “teach them how to be real revolutionaries.”

Critics such as Davis and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. wrote articles heralding the rise of these Black women writers. Others viewed their rise as an opportunity to sow division between them and their Black male contemporaries. Men and women from other ethnic groups signed on as honorary Black feminists bonding with a clique headed by Alice Walker in an attack on Black men. But we were literary comrades. In 1983 Baraka and his wife, the poet Amina Baraka, coedited Confirmation: An Anthology of African American Women. Their aim was to call attention to “black women’s low profile in the world of literature—and at the same time to do something about it,” he wrote in the book’s introduction. “How does one live under the rule and sway of national oppression, racism, and white supremacy? How does one keep one’s sanity and balance in such a world, and how is this further complicated by being not just black, but a woman?”

*

I’m used to traveling abroad as part of delegations of American scholars and writers and watching their astonishment when they confront Europeans who know more about BAM than they do. One is Ugo Rubeo, a scholar of American literature at the University of Rome. I visited his class in 2016 while negotiating with James Demby about publishing King Comus, the final novel written by his father, William Demby, who failed to find an American publisher before his death in 2013. While American politicians embarrass the country by denouncing Black syllabi (the current governor of Virginia won his position by campaigning against Morrison’s Beloved), Black literature is taught at some of the oldest universities in Europe, Africa, and China. Ugo told me that he “first heard about the Black Arts Movement in the early 1970s, reading Baraka’s critical pieces and Larry Neal’s articles.”

In recent decades I have befriended several scholars in China who work on Black Arts, including Liya Wang, Yanyu Zeng, and the late Yuqing Lin, who translated my novel Mumbo Jumbo into Chinese and persuaded the Chinese government to fund her research on my novel Japanese by Spring. I traveled to China in 2012 and 2015 and visited universities in Beijing and Xiangtan, in Hunan, where Carla directed my play “Mother Hubbard” with an all-Chinese cast.

In 1994 I attended the National Black Arts Festival in Atlanta, Georgia. The feuds of the 1960s were still simmering, even though Baraka had abandoned “racism” for interracial communism. Baraka complained that Black Arts had been coopted: “Even in this festival,” he insisted, “the Neals, Dumases, Sanchezes, Tourés, Madhabutis are packed into single readings while opposition forces…are given full range now to claim what we painfully struggled to bring into existence!” The New York Black Arts movement had originated in Umbra, but Baraka and Touré still boycotted an Umbra panel. One Black woman kept pestering me with outbursts about race-mixing. During the 2000s, however, some of the festival’s race purists reconnected with their white friends. One said that he sobbed when he read a white friend’s obituary in November 2020.

It wasn’t until 2014 that a new Black Arts movement arose. The revival occurred not in one of the country’s literary capitals but in a small town known for Gallo wine—Merced, California. It was launched by students, including white students, whose influence in establishing Black Studies has been unsung. (The Black Panther cofounder Bobby Seale once told me that Merritt College in Oakland would never have inaugurated a Black Studies program had white students not threatened to shut the school down.) The Associated Students of the University of California at Merced put up $40,000 for a conference free from the feuds, hatreds, hypocrisies, character assassination, racism, sexism, homophobia, and violence of the 1960s BAM. That conference and another at Dillard were organized by Kim McMillon, my collaborator for over three decades.

Last year, McMillon and an assistant editor, Kofi Antwi, edited the first volume of an anthology, Black Fire—This Time, which includes BAM pioneers and new voices.7 Like Alain Locke’s The New Negro in the 1920s, Neal and Baraka’s Black Fire was a report about the state of Black writing arts at the time of its publication. Neal and Baraka broadened the pool of talent, but most of the contributors were men—a step backward from the proportion of women in The New Negro and in Nancy Cunard’s Negro Anthology (1934). McMillon and Antwi’s volume, for which I wrote the foreword, is more expansive than Black Fire and corrects some of that anthology’s heavy-handed intolerance. It shows that the 2000s might be the golden age of Black writing. Perhaps this is why it also attracted the support of Henry Louis Gates, Jr., who also helped fund the Dillard conference.

In a recent essay for Public Books, Howard Rambsy II and Kenton Rambsy use search data to show that The New York Times Book Review has a habit of promoting what Locke called “the cultured few” and ignoring the wide swath of Black talent. (Unfortunately, Hispanic, Asian and Native American authors are hardly noticed in the review.) McMillon’s anthology shows how wide that swath of talent is. And regardless of the success of a few Black men and women who write, most Black writers, men and women, struggle to make ends meet.

What will be the legacy of the Black Arts Movement? For Spellman it was thanks to Black Arts “that so many African American artists are willing to build their own structures around their work.” He continued:

Perhaps that is the greatest legacy of the BAM—attitude. Along with the other activists of the era, Black artists worked hard to insinuate a strong sense of self among rising Black people, that we are beautiful and strong and capable of creating things that our progenitors would have thought to be miraculous. That we shine to the point of illumination. That we need tolerate no inhibiting forces. Yes, Say it loud…as the song goes.